Psychological Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Fernando Valley Burbank, Burbank Sunrise, Calabasas

Owens Valley Bishop, Bishop Sunrise, Mammoth Lakes, Antelope Valley and Mammoth Lakes Sunrise Antelope Valley Sunrise, Lancaster, Lancaster Sunrise, Lancaster West, Palmdale, Santa Clarita Valley and Rosamond Santa Clarita Sunrise and Santa Clarita Valley San Fernando Valley Burbank, Burbank Sunrise, Calabasas, Crescenta Canada, Glendale, Glendale Sunrise, Granada Hills, Mid San Fernando Valley, North East Los Angeles, North San Fernando Valley, North Hollywood, Northridge/Chatsworth, Sherman Oaks Sunset, Studio City/Sherman Oaks, Sun Valley, Sunland Tujunga, Tarzana/Encino, Universal City Sunrise, Van Nuys, West San Fernando Valley and Woodland Hills History of District 5260 Most of us know the early story of Rotary, founded by Paul P. Harris in Chicago Illinois on Feb. 23, 1905. The first meeting was held in Room 711 of the Unity Building. Four prospective members attended that first meeting. From there Rotary spread immediately to San Francisco California, and on November 12, 1908 Club # 2 was chartered. From San Francisco, Homer Woods, the founding President, went on to start clubs in Oakland and in 1909 traveled to southern California and founded the Rotary Club of Los Angeles (LA 5) In 1914, at a fellowship meeting of 6 western Rotary Clubs H. J. Brunnier, Presi- dent of the Rotary Club of San Francisco, awoke in the middle of the night with the concept of Rotary Districts. He summoned a porter to bring him a railroad sched- ule of the United States, which also included a map of the USA, and proceeded to map the location of the 100 Rotary clubs that existed at that time and organized them into 13 districts. -

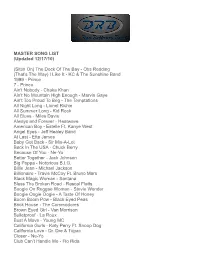

DRB Master Song List

MASTER SONG LIST (Updated 12/17/10) (Sittin On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding (That’s The Way) I Like It - KC & The Sunshine Band 1999 - Prince 7 - Prince Ain't Nobody - Chaka Khan Ain’t No Mountain High Enough - Marvin Gaye Ain’t Too Proud To Beg - The Temptations All Night Long - Lionel Richie All Summer Long - Kid Rock All Blues - Miles Davis Always and Forever - Heatwave American Boy - Estelle Ft. Kanye West Angel Eyes - Jeff Healey Band At Last - Etta James Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-A-Lot Back In The USA - Chuck Berry Because Of You - Ne-Yo Better Together - Jack Johnson Big Poppa - Notorious B.I.G. Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Billionaire - Travie McCoy Ft. Bruno Mars Black Magic Woman - Santana Bless The Broken Road - Rascal Flatts Boogie On Reggae Woman - Stevie Wonder Boogie Oogie Oogie - A Taste Of Honey Boom Boom Pow - Black Eyed Peas Brick House - The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl - Van Morrison Bulletproof - La Roux Bust A Move - Young MC California Gurls - Katy Perry Ft. Snoop Dog California Love - Dr. Dre & Tupac Closer - Ne-Yo Club Can’t Handle Me - Flo Rida Cowboy - Kid Rock Crazy - Gnarles Barkley Crazy In Love - Beyonce ft. Jay Z Dancing In The Streets - Martha and The Vendellas Disco Inferno - The Trammps DJ Got Us Falling In Love - Usher Don’t Stop Believing - Journey Don’t Stop The Music - Rihanna Drift Away - Uncle Kracker Dynamite - Taio Cruz Evacuate The Dance Floor - Cascada Everything - Michael Bublé Faithfully - Journey Feelin Alright - Joe Cocker Fight For Your Right - Beastie Boys Fly Away - Lenny Kravitz Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Free Fallin’ - Tom Petty Funkytown - Lipps, Inc. -

VVMF Education Guide

FOUNDERS OF THE WALL ECHOES FROM THE WALL War will always have impacts on society and culture. Within the realm of popular culture, music of the Vietnam era reflected a range of public opinion about military conflict. IN THE CLASSROOM Songs from Vietnam and Today DISCUSSION GUIDE This lesson plan will involve a review of popular music of the Vietnam era, as well as Begin by asking students to create list of songs that deal with the subject matter of war and peace, or are more broadly either highly patriotic, or highly more recent popular music that depict deal critical of problems in the nation. Which of the list are their favorites, and why? How Does Music with the subject matter of war and peace. Students will examine the perspectives of In the early days of the war, songs like Sgt. Barry Sadler’s “Ballad of the Green Berets” received extensive radio play—“Ballad of the Green Berets” reached #1 on Reflect Perspectives these songs and how the range of the Billboard Hot 100 in 1966. Listen to the song as it plays through slides 1-3, and ask perspectives was reflected in broader students to answer the song analysis questions included in the pre-visit activity above. Sgt. on War? society during and following the war. Barry Sadler served in Vietnam and wrote the song to celebrate the Green Beret Special Forces. This song has a clear perspective that celebrates the contributions of soldiers, yet it does not explicitly discuss political concerns or more broadly interpret the war. (click here for lyrics) Three years before the Ballad of the Green Berets topped the charts in 1966, Peter, Paul and Mary’s cover of “Blowin’ in the Wind” topped the Billboard charts, reaching #2 in 1963. -

Louisville Overall Score Reports

Louisville Overall Score Reports Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Solo Performance Double Platinum 1 318 Stupid Cupid - Elite Academy of Dance & Performing Arts - Louisville, KY 111.8 Olivia Grace Viers Double Platinum 1 322 I'm Cute - Studio Dance - Danville, KY 111.8 Landree Douglas Double Platinum 2 287 Best Years of Our Lives - Julia's Dance Academy - Fort Branch, IN 111.6 Emma Englebrecht Platinum 1st Place 3 114 Walking on Sunshine - Elite Academy of Dance & Performing Arts - Louisville, KY 110.5 Noelle Fain Platinum 1st Place 4 143 Catch My Breath - Elite Academy of Dance & Performing Arts - Louisville, KY 110.3 Brooke Reed Platinum 1st Place 5 130 Shake Your Tailfeather - Elite Academy of Dance & Performing Arts - Louisville, KY 109.5 Ella Kate Viers Gold 1st Place 6 103 Lips Be Moving - Turn Out Dance Studio - Murfreesboro, TN 108.1 Teagan Grace Gold 1st Place 7 314 Hawaii - Drake Dance Academy - Sellersburg, IN 107.9 Averie Thornton Gold 1st Place 8 281 Cruella De Vil - Julia's Dance Academy - Fort Branch, IN 107.8 Madison Riker Gold 1st Place 9 324 Cruella Deville - Studio Dance - Danville, KY 107.3 Bailey Kate Sparks Gold 1st Place 10 323 Bossy - Studio Dance - Danville, KY 107.2 Jossy Moses Advanced Platinum 1st Place 1 183 Evacuate the Dance Floor - Dreamz Dance Company - Louisville, KY 110.5 Mikyla Calbert Competitive Crystal Award 1 294 Bathing Beauty - Dance Designs - Prospect, KY 113.8 Ella Liberty Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Duet/Trio Performance Platinum 1st Place 1 131 Get Into My Car - Elite Academy of Dance & Performing Arts - Louisville, -

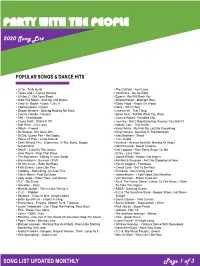

View the Full Song List

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

Most Requested Songs of 2019

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2019 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat. -

Metaphors of Love in 1946–2016 Billboard Year-End Number-One Songs

Text&Talk 2021; 41(4): 469–491 Salvador Climent* and Marta Coll-Florit All you need is love: metaphors of love in 1946–2016 Billboard year-end number-one songs https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2019-0209 Received June 25, 2019; accepted September 19, 2020; published online October 26, 2020 Abstract: This study examines the use of metaphors, metonymies and meta- phorical similes for love in a corpus of 52 year-end number one hit songs in the USA from 1946 to 2016 according to Billboard charts. The analysis is performed within the framework of Conceptual Metaphor Theory and from quantitative and quali- tative perspectives. Our findings indicate that the theme of romantic love is prevalent in US mainstream pop music over the course of seven decades but shows evolutionary features. Metaphors of love evolve from conventional to novel with a notable increase in both heartbreak and erotic metaphors. Remarkably, the study finds that the two predominant conceptualizations of love in pop songs – which in a significant number of cases overlap – are the following: experiential, originating in the physical proximity of the lovers, and cultural, reflecting possession by one lover and showing a non-egalitarian type of love. Keywords: Conceptual Metaphor Theory; corpus linguistics; metaphor; pop music; romantic love 1 Introduction The central theme of a large number of pop songs is some facet of romantic love. Starr and Waterman (2003: 105–110, 199–200) noted this to be already the case in the Tin Pan Alley era in the USA of the 1920s and 1930s and the trend continued through the 1940s and 1950s, when the entertainment industry grew exponen- tially: “total annual record sales in the United States rose from $191 million in 1951 to $514 million in 1959” (Starr and Waterman 2003: 252). -

Celebrity Playlists for M4d Radio’S Anniversary Week

Celebrity playlists for m4d Radio’s anniversary week Len Goodman (former ‘Strictly’ judge) Monday 28 June, 9am and 3pm; Thursday 1 July, 12 noon “I’ve put together an hour of music that you might like to dance to. I hope you enjoy the music I have chosen for you. And wherever you are listening, I hope it’s a ten from Len!” 1. Putting On The Ritz – Ella Fitzgerald 10. On Days Like These – Matt Monroe 2. Dream A Little Dream of Me – Mama 11. Anyone Who Had A Heart – Cilla Black Cass 12. Strangers On The Shore – Acker Bilk 3. A Doodlin’ Song – Peggy Lee 13. Living Doll – Cliff Richard 4. Spanish Harlem – Ben E King 14. Dreamboat – Alma Cogan 5. Lazy River – Bobby Darin 15. In The Summertime – Mungo Jerry 6. You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me – 16. Clair – Gilbert O’Sullivan Dusty Springfield 17. My Girl – The Temptations 7. When I Need You – Leo Sayer 18. A Summer Place – Percy Faith 8. Come Outside – Mike Sarne & Wendy 19. Kiss Me Honey Honey – Shirley Bassey Richard 20. I Want To Break Free – Queen 9. Downtown – Petula Clark Angela Lonsdale (Our Girl, Holby City, Coronation Street) Thursday 9am and 3pm; Friday 2 July, 12 noon Angela lost her mother to Alzheimer’s. Her playlist includes a range of songs that were meaningful to her and her mother and that evoke family memories. 1. I Love You Because – Jim Reeves (this 5. Crazy – Patsy Cline (her mother knew song reminds Angela of family Sunday every word of this song when she was lunches) in the care home, even at the point 2. -

Most Requested Songs of 2009

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on nearly 2 million requests made at weddings & parties through the DJ Intelligence music request system in 2009 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 5 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 6 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 7 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 8 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 9 B-52's Love Shack 10 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 11 ABBA Dancing Queen 12 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 13 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 14 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 15 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 16 Outkast Hey Ya! 17 Sister Sledge We Are Family 18 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 19 Kool & The Gang Celebration 20 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 21 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 22 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 23 Lady Gaga Poker Face 24 Beatles Twist And Shout 25 James, Etta At Last 26 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 27 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 28 Jackson, Michael Thriller 29 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 30 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 31 Commodores Brick House 32 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 33 Temptations My Girl 34 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 35 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 36 Bee Gees Stayin' Alive 37 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 38 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

Detroit II Results 2018

Detroit II May 4 – 6, 2018 Elite 8 Junior Miss StarQuest Elizabeth Szott - Boots - Karen's SChool of DanCe Elite 8 Teen Miss StarQuest Ava Mong - Lay Your Head Down - Great Lakes DanCe FaCtory Elite 8 Miss StarQuest Maris Ferguson - Pale Blue Dot - Great Lakes DanCe FaCtory Top SeleCt Junior Solo 1 - Elizabeth Szott - Boots - Karen's SChool of DanCe 2 - Elle Kemezis - Karma - Karen's SChool of DanCe 3 – Alaina Linders – Moonlight – Great Lakes DanCe FaCtory 4 - Teagan Ritter - Don't Rain On My Parade - Miss Lore's DanCe Rage Top SeleCt Teen Solo 1 - Abby Zenzen - Secrets - Miss Lore's DanCe Rage 2 - Alainna MeiCher - Intertwined - Great Lakes DanCe FaCtory 2 - Ava Mong - Lay Your Head Down - Great Lakes DanCe FaCtory 4 - Emily Zatelli - No Roots - Great Lakes DanCe FaCtory 5 - Anna Miller - Pusher - Great Lakes Dance FaCtory 6 - Libby Morante - Life On Mars - Big City DanCe Center 7 - Julia Lahr - When It All Falls Down - Studio G Performing Arts Center 8 - Ava Kuhn - Satan's Little Lamb - Karen's SChool of DanCe 9 - Emily Guillium - Purple Rain - Evolve DanCe Company 10 - Angelena Danowski - I'll Keep You Safe - Karen's SChool of DanCe 11 - Abby James - The Plight Of The Puppy Mill - Great Lakes DanCe FaCtory 12 - Rose Roberts - Teeth - Evolve Dance Company 13 - BroCk Ritter - Resolve - Miss Lore's Dance Rage 14 - Hailey PetroviCh - In The Embers - Dare 2 DanCe 15 - Rylee MitChell - When You Love Someone - Evolve Dance Company Top SeleCt Senior Solo 1 - Maris Ferguson - Pale Blue Dot - Great Lakes DanCe FaCtory 2 - Isabelle LesCelius -

Top500 Final

1. MICHAEL JACKSON Billie Jean 2. EAGLES Hotel California 3. BON JOVI Livin’ On A Prayer 4. ROLLING STONES Satisfaction 5. POLICE Every Breath You Take 6. ARETHA FRANKIN Respect 7. JOURNEY Don’t Stop Believin’ 8. BEATLES Hey Jude 9. GUESS WHO American Woman 10. QUEEN Bohemian Rhapsody 11. MARVIN GAYE I Heard It Through The Grapevine 12. JOAN JETT I Love Rock And Roll 13. BEE GEES Night Fever 14. BEACH BOYS Good Vibrations 15. BLONDIE Call Me 16. FOUR SEASONS December 1963 (Oh, What A Night) 17. BRYAN ADAMS Summer Of 69 18. SURVIVOR Eye Of The Tiger 19. LED ZEPPELIN Stairway To Heaven 20. ROY ORBISON Pretty Woman 21. OLIVIA NEWTON JOHN Physical 22. B.T.O. Takin’ Care Of Business 23. NEIL DIAMOND Sweet Caroline 24. DON McLEAN American Pie 25. TOM COCHRANE Life Is A Highway 26. BOSTON More Than A Feeling 27. MICHAEL JACKSON Rock With You 28. ROD STEWART Maggie May 29. VAN HALEN Jump 30. ELTON JOHN/ KIKI DEE Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 31. FOUR SEASONS Big Girls Don’t Cry 32. FLEETWOOD MAC Dreams 33. FIFTH DIMENSION Aquarius/Let The Sunshine In 34. HALL AND OATES Maneater 35. NEIL YOUNG Heart Of Gold 36. PRINCE When Doves Cry 37. EAGLES Lyin’ Eyes 38. ARCHIES Sugar, Sugar 39. THE KNACK My Sharona 40. BEE GEES Stayin’ Alive 41. BOB DYLAN Like A Rolling Stone 42. AMERICA Sister Golden Hair 43. ALANNAH MYLES Black Velvet 44. FRANKI VALLI Grease 45. PAT BENATAR Hit Me With Your Best Shot 46. EMOTIONS Best Of My Love 47.