The Hostess at the Border: an Emergent Anachronism Elena Knox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Prometheus to Pistorius: a Genaelogy of Physical Ability

FROM PROMETHEUS TO PISTORIUS: A GENAELOGY OF PHYSICAL ABILITY by Stephanie J. Cork A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September, 2011) Copyright ©Stephanie J. Cork, 2011 Abstract (Fragile Frames + Monstrosities)ModernWar + (Flagged Bodies + Cyborgs)PostmodernWar = dis-AbilityCyborged ii Acknowledgements A huge thank you goes out to: my friends, colleagues, office neighbours, mentors, family, defence committee, readers, editors and Steve. Thank you, also, to the Canadian and American troops as well as Paralympic athletes, Oscar Pistorius and Aimee Mullins for their inspiration, sorry, I have borrowed your stories to perpetuate my own academic success. Thanks also to Louise Bark for her endless patience and kindness, as well as a pint (or three!) at Ben’s Pub. Anne and Wendy and especially Michelle: you are lifesavers! Finally, my eternal gratitude to the: “greatest man alive,” Dr. Rob Beamish (Scott Mason 2011). iii Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents............................................................................................................................ iv Chapter 1: Introduction.....................................................................................................................1 -

Pdf • Cynthia Breazeal

© copyright by Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeime, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, and Selma Sabanovic 2019. https://www.human-robot-interaction.org Human{Robot Interaction An Introduction Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeme, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, Selma Sabanovi´cˇ This material has been published by Cambridge University Press as Human Robot Interaction by Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeime, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, and Selma Sabanovic. ISBN: 9781108735407 (http://www.cambridge.org/9781108735407). This pre-publication version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © copyright by Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeime, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, and Selma Sabanovic 2019. https://www.human-robot-interaction.org This material has been published by Cambridge University Press as Human Robot Interaction by Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeime, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, and Selma Sabanovic. ISBN: 9781108735407 (http://www.cambridge.org/9781108735407). This pre-publication version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © copyright by Christoph Bartneck, Tony Belpaeime, Friederike Eyssel, Takayuki Kanda, Merel Keijsers, and Selma Sabanovic 2019. https://www.human-robot-interaction.org Contents List of illustrations viii List of tables xi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 About this book 1 1.2 Christoph -

Examining the Use of Robots As Teacher Assistants in UAE

Volume 20, 2021 EXAMINING THE USE OF ROBOTS AS TEACHER ASSISTANTS IN UAE CLASSROOMS: TEACHER AND STUDENT PERSPECTIVES Mariam Alhashmi* College of Education, Zayed University, [email protected] Abu Dhabi, UAE Omar Mubin Senior Lecturer in Human Computer [email protected] Interaction, Sydney, Australia Rama Baroud Part-Time Research Assistant [email protected] * Corresponding author ABSTRACT Aim/Purpose This study sought to understand the views of both teachers and students on the usage of humanoid robots as teaching assistants in a specifically Arab context. Background Social robots have in recent times penetrated the educational space. Although prevalent in Asia and some Western regions, the uptake, perception and ac- ceptance of educational robots in the Arab or Emirati region is not known. Methodology A total of 20 children and 5 teachers were randomly selected to comprise the sample for this study, which was a qualitative exploration executed using fo- cus groups after an NAO robot (pronounced now) was deployed in their school for a day of revision sessions. Contribution Where other papers on this topic have largely been based in other countries, this paper, to our knowledge, is the first to examine the potential for the inte- gration of educational robots in the Arab context. Findings The students were generally appreciative of the incorporation of humanoid robots as co-teachers, whereas the teachers were more circumspect, express- ing some concerns and noting a desire to better streamline the process of bringing robots to the classroom. Recommendations We found that the malleability of the robot’s voice played a pivotal role in the for Practitioners acceptability of the robot, and that generally students did well in smaller Accepting Editor Minh Q. -

Planetary Exploration Using Bio Inspired Technologies

© 2016 California Institute of Technology. Government sponsorship acknowledged. Planetary exploration using bio inspired technologies Ref.: Y. Bar-Cohen & D. Hanson “Humanlike Robots” 2009. Courtesy of Adi Marom, Graphics Artist. Yoseph Bar-Cohen, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology http://ndeaa.jpl.nasa.gov/ Who really invented the wheel? Ref: http://www.natgeocreative.com/photography/1246755 2 Biology – inspiring human innovation Honeycomb structures are part of almost every aircraft The fins were copied to significantly improve Flying was enabled using aerodynamic swimming and diving principles http://www.wildland.com/trips/details/326/ne The spider is quite an w_zealand_itin.aspx “engineer”. Its web may have inspired the fishing net, fibers, clothing and others. http://www.swimoutlet.com/Swim_Fins _s/329.htm The octopus as a model for biomimetics Adaptive shape, texture and camouflage of the Octopus Courtesy of William M. Kier, of North Carolina Courtesy of Roger T. Hanlon, Director, Marine Resources Center, Marine Biological Lab., MA Camouflage has many forms The swan puffs its wings to look Jewel Scarab Beetles - Leafy seadragon bigger in an attack posture bright colors appear bigger Butterfly - Color matching Owl butterfly Wikipedia freely licensed media Lizard - Color matching http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Owl_butterfly 5 Plants use of camouflage • To maximize the pollination opportunities - flowers are as visible as possible. • To protect from premature damage – initially, fruits are green, have sour taste, and are camouflaged by leaves. • Once ripped, fruits become colorful and tasty, as well as have good smell Biomimetic robotic exploration of the universe The mountain goat is an inspiring model for all- terrain legged rovers The Curiosity rover and the Mars Science Laboratory MSL) landed on Mars in Aug. -

Bluecover C-Bfront

! 0%67(KNO5VWFKGU%GPVGT $NWG/CIRKG'ZRGTKOGPVCN(KNO 5GTKGU6CKYCP ⛑䍄繷灓⻇洸㉒⼶ 5GRVGODGTł,CPWCT[ *WOCPKVKGU$WKNFKPI0%67%KPGOCHQTVJG#TVU *55 (KNO 5ETGGPKPI5EJGFWNG (TGG#FOKUUKQP RORO 㞎㤁⨑熿獌⧬䶬ↅ聆Ⰸ⹙砕㬂☡ ↛䰟Ⅽ氉 ↅⰈ↛㡨槜㉒楃 *55 㞎㤁羝峫獌哋䠒⑆⬕苌㺰⢏⬕禈磢桴䎛䡗Ⰺ 哨 5%*'&7.' 9/27/2017 ZANY EXPERIMENTAL ANIMATION AND MONTAGE •!M. Woods, THE DOCTOR IS IN (Digitized Mechanomorphic Consciou{SIC}ness Landscape #5) (USA 2016) 00:02:26 •!Adrián Regnier Chavez, A. (Mexico 2015) 00:07:13 •!Adrián Regnier Chavez, U. (Mexico 2014) 00:04:40 •!Naween Noppakun, WE LOVE ME (Thailand 2017) 00:13:00 •!Paul Wiersbinski, FLY HIGH OR I FLY ABOVE YOU (Germany 2016) 00:7:00 •!Victoria Karmin, EXTRATERRESTRIAL (Mexico 2015) 00:15:00 •!Deborah Kelly, BEASTLINESS (Australia 2011) 00:04:32 •!Jean-Michel Rolland, CARS MELODY (France 2011) 00:05:32 •!Marcantonio Lunardi, UNUSUAL JOURNEY (Italy 2017) 00:03.22 •!Marcantonio Lunardi, THE CAGE (Italy 2016) 00:05:47 •!Marcantonio Lunardi, ANTHROPOMETRY 154855 (Italy 2016) 00:03:36 •!Martin Sulzer, WETWARE (Germany 2017) 00:04:30 •!Przemek Wegrzyn, SECURITY MEASURES (Poland, 2015) 00:05:55 •!Bob Georgeson, WHY IS THIS HAPPENING? (Australia 2015) 00:07:31 10/18/2017 THE BODY—DANCE AND HAPTIC VISUALITY •!Anouska Samms and Sofia Pancucci-McQueen, THE BATHS (UK 2014– 2016) 00:012:27 •!Mark Freeman, BODY WITHOUT A BRAIN (US 2014) 00:06:50 •!Mark Freeman, BODY/BAG (US 2017) 00:02:45 •!Jean-Michel Rolland, THE RACE/LA COURSE (France 2013) 00:03:45 •!Suhrke/Skevik: Hilde Skevik and Ellen Henriette Suhrke, TRANSACTIONS #1 (Norway 2011) 00:03:44 •!Nishat Hossain, 45 MINUTES (USA 2016) 00:10:00 •!Suhrke/Skevik: Hilde Skevik and Ellen Henriette Suhrke, TRANSACTIONS #2 (Norway 2011) 00:05:42 •!Luna Rousseau/Nathan Israel/Thomas Israel/Kika Nicolela, THE MUD MAN/L'HOMME DE BOUE) (Belgium 2017) 00:010:02 •!Pete Burkeet, MANNEQUIN (USA, 2017) 00:07:58 •!Jeremy J. -

Assistive Humanoid Robot MARKO: Development of the Neck Mechanism

MATEC Web of Conferences 121, 08005 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/ matecconf/201712108005 MSE 2017 Assistive humanoid robot MARKO: development of the neck mechanism Marko Penčić1,*, Maja Čavić1, Srđan Savić1, Milan Rackov1, Branislav Borovac1, and Zhenli Lu2 1Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad, TrgDositejaObradovića 6, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia 2School of Electrical Engineering and Automation, Changshu Institute of Technology, Hushan Road 99, 215500 Changshu, People's Republic of China Abstract.The paper presents the development of neck mechanism for humanoid robots. The research was conducted within the project which is developing a humanoid robot Marko that represents assistive apparatus in the physical therapy for children with cerebral palsy.There are two basic ways for the neck realization of the robots. The first is based on low backlash mechanisms that have high stiffness and the second one based on the viscoelastic elements having variable flexibility. We suggest low backlash differential gear mechanism that requires small actuators. Based on the kinematic-dynamic requirements a dynamic model of the robots upper body is formed. Dynamic simulation for several positions of the robot was performed and the driving torques of neck mechanism are determined.Realized neck has 2 DOFs and enables movements in the direction of flexion-extension 100°, rotation ±90° and the combination of these two movements. It consists of a differential mechanism with three spiral bevel gears of which the two are driving and are identical, and the third one which is driven gear to which the robot head is attached. Power transmission and motion from the actuators to the input links of the differential mechanism is realized with two parallel placed gear mechanisms that are identical.Neck mechanism has high carrying capacity and reliability, high efficiency, low backlash that provide high positioning accuracy and repeatability of movements, compact design and small mass and dimensions. -

HBS-1: a Modular Child-Size 3D Printed Humanoid

robotics Article HBS-1: A Modular Child-Size 3D Printed Humanoid Lianjun Wu, Miles Larkin, Akshay Potnuru and Yonas Tadesse * Received: 6 November 2015; Accepted: 4 January 2016; Published: 13 January 2016 Academic Editor: Huosheng Hu Humanoid, Biorobotics and Smart Systems Laboratory (HBS Lab), Department of Mechanical Engineering, The University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson TX 75080, USA; [email protected] (L.W.); [email protected] (M.L.); [email protected] (A.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-972-883-4556; Fax: +1-972-883-4659 Abstract: An affordable, highly articulated, child-size humanoid robot could potentially be used for various purposes, widening the design space of humanoids for further study. Several findings indicated that normal children and children with autism interact well with humanoids. This paper presents a child-sized humanoid robot (HBS-1) intended primarily for children’s education and rehabilitation. The design approach is based on the design for manufacturing (DFM) and the design for assembly (DFA) philosophies to realize the robot fully using additive manufacturing. Most parts of the robot are fabricated with acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) using rapid prototyping technology. Servomotors and shape memory alloy actuators are used as actuating mechanisms. The mechanical design, analysis and characterization of the robot are presented in both theoretical and experimental frameworks. Keywords: humanoid; mechanical design; actuators; manufacturing; 3D printing 1. Introduction Humanoid robots have great potential for use in our daily life by accompanying or working together with people. Growing interest in humanoid robots has spurred a substantial increase in their development over the past decade. -

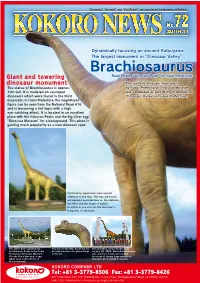

Brachiosaurus Brachiosaurus

“Doukoku”“Actroid”, and“Pet Robot” are registered trademarks of Kokoro. Dynamically focusing on ancient Katsuyama The largest monument in“Dinosaur Valley” Brachiosaurus Road Parking“Dinosaur Road” (in Fukui Prefecture) Giant and towering dinosaur monument The realistic dinosaur monument The statue of Brachiosaurus is approx. by Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum 10m tall. It is modeled on sauropod was completed as part of the promotion of dinosaurs which were found in the third “Dinosaur Valley” in Fukui Prefecture. excavation in Fukui Prefecture.The magnificent figure can be seen from the National Road 416 and is becoming a hot topic with a high eye-catching effect. It is located in an excellent place with the Hakusan Peaks and the big silver egg “Dinosaur Museum” for a background. This place is gaining much popularity as a new dinosaur spot. Particularly, supervisors paid special attention to the legs. The legs are based on repeated consideration on the skeleton, the flesh and the shape of cuticle. In addition, you can see the dinosaur’s footprints on the base. The silver dome gleaming in The face is like this. It can hardly The unveiling ceremony was held the Hakusan Peaks is the Fukui be seen because it is placed high on July 10, 2009. When Brachiosaurus Prefectural Dinosaur Museum. in the air. was unveiled, it was surrounded It looks like a dinosaur’s egg by a roar of cheers from preschool when seen from in front of kids who were invited as guests. the monument. KOKORO COMPANY LTD Tel: +81 3-3779-8506 Fax: +81 3-3779-8426 20F Osaki New City TOC Building No.1,1-6-1,Osaki, Shinagawa-ku,Tokyo 141-8603 JAPAN web: http://www.kokoro-dreams.co.jp/english/index.html Intelligent Interaction Icon Robot NEW PRODUCT As its name suggests, I-FAIRY is an information robot based on the image of a lovely fairy. -

Robotics in Germany and Japan DRESDEN PHILOSOPHY of TECHNOLOGY STUDIES DRESDNER STUDIEN ZUR PHILOSOPHIE DER TECHNOLOGIE

Robotics in Germany and Japan DRESDEN PHILOSOPHY OF TECHNOLOGY STUDIES DRESDNER STUDIEN ZUR PHILOSOPHIE DER TECHNOLOGIE Edited by /Herausgegeben von Bernhard Irrgang Vol./Bd. 5 Michael Funk / Bernhard Irrgang (eds.) Robotics in Germany and Japan Philosophical and Technical Perspectives Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Robotics in Germany and Japan : philosophical and technical perspectives / Michael Funk, Bernhard Irrgang (eds.). pages cm ----- (Dresden philosophy of technology perspectives, ISSN 1861- -- 423X ; v. 5) ISBN 978-3-631-62071-7 ----- ISBN 978-3-653-03976-4 (ebook) 1. Robotics-----Germany----- Popular works. 2. Robotics----- Japan--Popular works. 3. Robotics-----Philosophy. I. Funk, Michael, 1985- -- editor of compilation. II. Irrgang, Bernhard, editor of compilation. TJ211.15.R626 2014 629.8'920943----- dc23 2013045885 Cover illustration: Humanoid Robot “ARMAR” (KIT, Germany), Photograph: Michael Funk An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISSN 1861-423X • ISBN 978-3-631-62071-7 (Print) E-ISBN 978-3-653-03976-4 (E-PDF) • E-ISBN 978-3-653-99964-8 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-653-99963-1 (MOBI) • DOI 10.3726/978-3-653-03976-4 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 unported license. -

Increasing User Confidence in Privacy-Sensitive Robots by Raniah

Increasing User Confdence in Privacy-Sensitive Robots by Raniah Abdullah Bamagain Bachelor of Science Information Technology Computing and Information Technology 2012 A thesis submitted to the College of Computer Engineering and Sciences at Florida Institute of Technology in partial fulfllment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Assurance and Cybersecurity Melbourne, Florida May, 2019 ⃝c Copyright 2019 Raniah Abdullah Bamagain All Rights Reserved The author grants permission to make single copies. We the undersigned committee hereby approve the attached thesis Increasing User Confdence in Privacy-Sensitive Robots by Raniah Abdullah Bamagain Marius Silaghi, Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of Computer Engineering and Sciences Committee Chair Hector Gutierrez, Ph.D. Professor Department of Mechanical and Civil Engineering Outside Committee Member Lucas Stephane, Ph.D. Assistant Professor Department of Computer Engineering and Sciences Committee Member Philip Bernhard, Ph.D Associate Professor and Head Department of Computer Engineering and Sciences ABSTRACT Title: Increasing User Confdence in Privacy-Sensitive Robots Author: Raniah Abdullah Bamagain Major Advisor: Marius Silaghi, Ph.D. As the deployment and availability of robots grow rapidly, and spreads everywhere to reach places where they can communicate with humans, and they can constantly sense, watch, hear, process, and record all the environment around them, numerous new benefts and services can be provided, but at the same time, various types of privacy issues appear. Indeed, the use of robots that process data remotely causes privacy concerns. There are some main factors that could increase the capabil- ity of violating the users' privacy, such as the robots' appearance, perception, or navigation capability, as well as the lack of authentication, the lack of warning sys- tem, and the characteristics of the application. -

Robotopia Rising – Next Generation of Robots in Japan Brings SF Closer to Fact – by Tim Hornyak

COVER STORY • 9 Robotopia Rising – Next Generation of Robots in Japan Brings SF Closer to Fact – By Tim Hornyak Photos: Greg McCartney The children were completely ingly fast industrial robots have been immersed in the battle being fought turning out everything from luxury before their eyes. Two teams struggled sedans to printer cartridges, batteries, to gain control of the ball, get it across and, of course, more robots. Japan the pitch and slot it home into the became the most automated place on enemy’s net. When at last one of the earth, but now a new generation of strikers booted it between the posts, the robots designed to help and entertain kids cheered with delight. This was ordinary people instead of improving soccer with a twist – all the players corporate productivity is quickly grow- were robots, humanoid machines that ing up. kids can build and control themselves. The 2005 Aichi Expo held outside It is the latest trend in a technological Nagoya was a world fair that stood out revolution that is sweeping Japan as not only for its 22 million visitors but robots are finally moving out of the fac- for showcasing about 70 types of new tory and into homes across the country. robots that included security patrol machines working on-site, humanoids Big in Japan that marched in a musical band, and lifelike, interactive androids. In fact, Japan has dominated global robotics robots stole the show. Such exhibitions development since robots began work- are nothing new – Expo ‘85 in Tim Hornyak, author ing in manufacturing plants in the Tsukuba, northeast of Tokyo, for of “Loving the Machine: The Art 1970s. -

FCJ-204 Degrees of Freedom

FCJ-204 Degrees of Freedom Elena Knox, Waseda University. Abstract: This paper critiques a choreographed performance of embodied agency by a ‘very humanlike’ (Ishiguro, 2006) gynoid robot. It draws on my experience in 2013 with Actroid-F (or Geminoid-F), designed by ATR Hiroshi Ishiguro Laboratories, when I created six artworks making up Actroid Series I. My analysis here proceeds from and through the part-programmed, part-puppeteered actions and vocalisations of Actroid-F for my six-minute video Radical Hospitality, in which the robotic gynoid actor performs compound negotiations of embodied authority, docility, and compliance. Design of ‘very humanlike’ androids risks instilling into robotic agents existing and discriminatory societal standards. My performance, installation and screen works trouble the gendered aesthetics predominant in this realm of engineering design. doi: 10.15307/fcj.28.204.2017 This paper critiques a choreographed performance of embodied agency by a 'very humanlike' (Ishiguro, 2006) gynoid robot. It draws on my experience at the Creative Robotics Lab, UNSW Australia, in 2013, with Actroid-F (or Geminoid-F), designed by ATR Hiroshi Ishiguro Laboratories [1], when I created six artworks making up Actroid Series I (2015). My analysis here proceeds from and through the part-programmed, part- puppeteered actions and vocalisations of Actroid-F in my six-minute video Radical Hospitality, in which the robotic gynoid actor performs compound negotiations of embodied authority, docility, and compliance. All six artworks in the series seek to induce moments of feminist hyper-awareness, or cognitive lysis (Randolph, 2001), that work against the normalisation of instilling gendered societal restrictions into humanoid robots via their embodiments and functionalities.