J U D G M E N T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE 9432877230 SINGH PERSONNEL AND ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS & HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 14-01-1962 E-GOVERNANCE DEPTT. 2 SUVENDU GHOSH 1990 ADDITIONAL DIRECTOR B 18/204, A-B CONNECTOR, +918902267252 (CS1990027 ) B.R.A.I.P.R.D. (TRAINING) KALYANI ,NADIA, WEST suvendughoshsiprd Dob- 21-06-1960 BENGAL 741251 ,PHONE:033 2582 @gmail.com 8161 3 NAMITA ROY 1990 JT. SECY & EX. OFFICIO NABANNA ,14TH FLOOR, 325, +919433746563 MALLICK DIRECTOR SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1990036 ) INFORMATION & CULTURAL ROAD,HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 28-09-1961 AFFAIRS DEPTT. ,PHONE:2214- 5555,2214-3101 4 MD. ABDUL GANI 1991 SPECIAL SECRETARY MAYUKH BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, +919836041082 (CS1991051 ) SUNDARBAN AFFAIRS DEPTT. BIDHANNAGAR, mdabdulgani61@gm Dob- 08-02-1961 KOLKATA-700091 ,PHONE: ail.com 033-2337-3544 5 PARTHA SARATHI 1991 ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER COURT BUILDING, MATHER 9434212636 BANERJEE BURDWAN DIVISION DHAR, GHATAKPARA, (CS1991054 ) CHINSURAH TALUK, HOOGHLY, Dob- 12-01-1964 ,WEST BENGAL 712101 ,PHONE: 033 2680 2170 6 ABHIJIT 1991 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SHILPA BHAWAN,28,3, PODDAR 9874047447 MUKHOPADHYAY WBSIDC COURT, TIRETTI, KOLKATA, ontaranga.abhijit@g (CS1991058 ) WEST BENGAL 700012 mail.com Dob- 24-12-1963 7 SUJAY SARKAR 1991 DIRECTOR (HR) BIDYUT UNNAYAN BHAVAN 9434961715 (CS1991059 ) WBSEDCL ,3/C BLOCK -LA SECTOR III sujay_piyal@rediff Dob- 22-12-1968 ,SALT LAKE CITY KOL-98, PH- mail.com 23591917 8 LALITA 1991 SECRETARY KHADYA BHAWAN COMPLEX 9433273656 AGARWALA WEST BENGAL INFORMATION ,11A, MIRZA GHALIB ST. agarwalalalita@gma (CS1991060 ) COMMISSION JANBAZAR, TALTALA, il.com Dob- 10-10-1967 KOLKATA-700135 9 MD. -

Role of District Magistrate Move with the Changing Times

Prof. Shashi Sharma, Principal Professor, Department of Political Science e-mail: [email protected] Role of District Magistrate Move with the Changing Times Introduction District Administration the legacy of British Raj is the principal unit of territorial administration and has been the nodal point of the administrative system in India . District is considered as the as the principal position of administration for purpose of revenue administration and maintenance of the law and order. The district as the primary unit of administration or as the foundation the administrative set up has for long been a “Pivotal Point of Contact” between the citizens and the administration. The success of district administration, therefore builds the success of state administration. District Magistrate IAS officers (Known as Collectors) were generally held in high regard as incorruptible and good administrators in colonial era. Upon independence, the new Republic of India accepted the then serving Indian civil service officers who choose to stay on rather than leave for the UK and renamed the service the Indian Administrative Service. The Basic territorial unit of administration in India is the district and district administration is the total management of public affairs within this unit. District Collector was the pivot of district administration and represents the state government in its totality. The involvement of the Collector in development administration would not only make his role more meaningful and satisfying but also the district level coordination more effective. The supervisory role of District Collector in development process in the district must be maintained as he is supreme authority and his role provided by Constitution can not be undermined by any other agency. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

District Collectorate

District Collectorate District is the basic unit of administration in a state and District Collector (ZIladhikari) or the District Magistrate (Zila Magistrate) is the head of the District Administration in Uttar Pradesh. He is appointed by the State Government and is a member of the Indian Administrative Service (I.A.S.) recruited by the Central Government. He has wide powers and manifold responsibilities. In many ways he is chief custodian of law and authority, the pivot on which runs the local administration. Bareilly Collector or the D.M. works under the administrative control of Commissioner of Bareilly Division who also is member of the I.A.S. Officer Office Contact Number Email-id District Room no.1, Collectorate office, 9454417524, 0581-2558764, 0581- [email protected] Magistrate Civil lines Bareilly 2557147 Fax: 0581-2557001 Room no. 5,Collectorate office, ADM E 9454417197 Bareilly Room no. 15,Collectorate office, ADM CITY 9454417198 Bareilly City Room no. 17,Collectorate office, 9454417199 Magistrate Bareilly ACM-1 Collectorate office, Bareilly ACM-2 Collectorate office, Bareilly ACM-3 Collectorate office, Bareilly ACM-4 Collectorate office, Bareilly District Collector is the executive head of the district with numerous responsibilities in the sphere of revenue administration, civil administration, development, panchayats, local bodies, etc. Due to immense importance of her office, the District Collector is considered to be the measuring rod of efficiency in administration. Functionally the district administration is carried on through the various Departments of the State Government each of which has an office of its own in the district level. The District Collector is the executive leader of the district administration and the District Officers of the various Departments in the district render technical advice to her in the discharge of her duties. -

Sl. No Districtname CUG Mobile STD Code OFFICE FAX E-Mail 1 Agra

UP District Magistrate's Contact Details Sl. DistrictName CUG Mobile STD Code OFFICE FAX E-mail No 1 Agra 9454417509 0562 2260184 2364718 [email protected] 2 Aligarh 9454417513 0571 2400202 2407555 [email protected] 3 Allahabad 9454417517 0532 2250253 2640290 [email protected] 4 Ambedkarnagar 9454417539 05271 244250 244107 [email protected] 5 Amethi 9454418891 05368 244577 6 Auraiya 9454417550 05683 245528 244888 [email protected] 7 Azamgarh 9454417521 05462 220930 260430 [email protected] 8 Baghpat 9454417562 0121 2220520 2221900 [email protected] 9 Bahraich 9454417535 05252 232815 232648 [email protected] 10 Ballia 9454417522 05498 220879 220648 [email protected] 11 Balrampur 9454417536 05263 233942 232368 [email protected] 12 Banda 9454417531 05192 224632 220244 [email protected] 13 Barabanki 9454417540 05248 222730 222629 [email protected] 14 Bareilly 9454417524 0581 2473303 2557001 [email protected] 15 Basti 9454417528 05542 247155 246403 [email protected] 16 Bijnor 9454417570 01342 262222 262046 [email protected] 17 Budaun 9454417525 05832 266406 269306 [email protected] 18 Bulandshahar 9454417563 05732 224351 280898 [email protected] 19 Chandauli 9454417576 05412 262555 262500 [email protected] 20 Chitrakoot 9454417532 05198 235018 235305 [email protected] 21 Deoria 9454417543 05568 222316 222519 [email protected] 22 Etah 9454417514 05742 233302 233860 [email protected] 23 Etawah 9454417551 05688 254770 252758 [email protected] 24 Faizabad 9454417541 05278 224286 222214 [email protected] 25 Farrukhabad 9454417552 05692 234133 234256 [email protected] 26 Fatehpur 9454417518 05180 -

Chief Minister Calls on Governor of Sikkim Government Will Ensure That

ikkim heral s Vol. 63 No. 22 visit us at www.ipr.sikkim.gov.in Gangtok (Friday) April 17, 2020 Regd. No.WBd/SKM/01/2017-19 Chief Minister calls on Government will ensure that the lock down Governor of Sikkim is more severe this time- Chief Minister Gangtok, April 14: Chief Minister Mr. Prem Singh Tamang convened a press conference today to share the decisions taken in the Cabinet Meeting which was held today with regard to the steps taken by the Government so far to combat Covid-19, and further decisions with regard to extension of lock- down. He expressed his gratitude to the people of Sikkim, Government officials, and front line workers for their relentless service to keep the State free from Covid- 19. The Chief Minister informed Gangtok, April 16: The Chief contain spread of the COVID-19. that the State of Sikkim will India. He added that slight contain Covid-19 in the State. Minister Mr. Prem Singh Tamang He also briefed the Governor continue to abide by lock-down relaxation could be made after the Speaking about the steps called on Governor Mr. Ganga about the steps taken to distribute norms till the 3rd of May, 2020, duly 20th of April, to selective sectors taken by the State before the Prasad at Raj Bhawan, today to the relief material which has been complying by the direction of the like agriculture, construction, small initiatial period of lock down was brief about the decisions taken by carried out successfully. An Prime Minister of India. He said industries, duly maintaining social announced, he said that the State the State Government after the additional list of 29000 beneficiaries that the Government will ensure distancing. -

Office of the District Magistrate (East) Delhi Urban Development Agency (District-East) L.M

OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT MAGISTRATE (EAST) DELHI URBAN DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (DISTRICT-EAST) L.M. BANDH, SHASTRI NAGAR, DELHI-110031 No. Misc./DUDA/EAST/2018-2019/Q I - 116 c Dated: I9 Minutes of 2nd Meeting of Governing Body of DUDA (East) held on 18.04.2018 at 11:30 A.M. in the Conference Room of DM (East), L.M. Bundh, Shastri Nagar, Delhi-110031 1. The 2nd Meeting of Governing Body of DUDA (East) was held on 18.04.2018 at 11:30 A.M. in the Conference Room of DM (East), L.M. Bundh, Shastri Nagar, Delhi-110031. The list of participants is annexed as Annexure-I. 2. Out of 17 members of the Governing Body, 13 members/representatives were present. As per bye laws of the society, 1/3rd of the member of the Governing Body present in person forms the quorum. The quorum was therefore found complete. 3. In the absence of Chairperson, DUDA (East), the meeting was chaired by the Project Director cum Additional District Magistrate (East). 4. The Project Director, DUDA (East) welcomed all the members of the Governing Body. Thereafter, the agenda items were taken up point wise for discussion and the following decisions were taken in the meeting:- i) Agenda item No.1:- Confirmation of minutes/decision taken in 1.5t Governing Body Meeting — The minutes of the first Governing Body meeting related to point 3 & 7 of Resolution No.1 was approved by the Governing Body. ii) Agenda item No.2:- Intimation regarding appointment of registered Chartered Accountant for Audit of Accounts of DUDA (East) for the F.Y. -

The West Bengal Separation of Judicial and Executive Functions Act, 1968

,-7- 7.116..x-Tereear. THE WEST BENGAL SEPARATION OF JUDICIAL AND EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS ACT, 1968 No. 8 of 1968 [26th March 19681 Enacted by the President in the Nineteenth Year of the Republic of India. An Act to provide for the separation of the Judiciary from the Executive in the public services in the State of West Bengal. In exercise of the powers conferred by section 8 of the West Bengal State Legislature (Delegation of Powers) Act, of 1968, 1968, the President is pleased to enact as follows: — 1. (1) This Act may be called the West Bengal Short title, Separation of Judicial and Executive Functions Act, 1968. extent and (2) It extends to the whole of the State of West Bengal. ocreomment. (3) This section and section 8 shall come into force at once, and the remaining- provisions of this Mt shall come into force on such date as the State Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint and different dates may be appointed for different districts and any reference in this Act to its commencement shall, in relation to a district, ba construed as a reference to the coming into force of those provisions therein. 2. In this Act, "Code of Criminal Procedure" means Definition. the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898. 5 oft ills. 3, The Code of Criminal Procedure shall, in its appli- Amend- cation to the State of West Bengal, be amended in the mints in manner and to the extent specified in the Schedule. the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898. 4. Notwithstanding anything to the contrary contained Classes of in any other law for the time being in force, the word Magis- "Magistrate" shall include the following two classes of traces. -

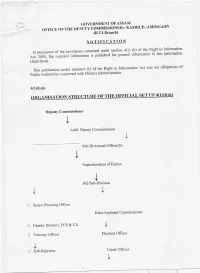

ORGANISATION STRUCTURE of the OFFICIAL SET up 4(1)(B)(I)

GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER:: KAMRUP::AMINGAON (R.T.I.Branch) NOTIFICATION In pursuance of the provisions contained under section 4(1) (b) of the Right to Information Act, 2005, the required information is published for general information in this Information Hand Book. This publication under section4 (1) of the Right to Information Act sets out obligations of Public Authorities concerned with District Administration. 4(1)(b)(i) ORGANISATION STRUCTURE OF THE OFFICIAL SET UP 4(1)(b)(i) Deputy Commissioner Addl. Deputy Commissioner Sub-Divisional Officer(S) 4, Superintendent of Excise HQ Sub-Division Senior Planning Officer Extra Assistant Commissioner ❑ Deputy Director, FCS & CA ❑ Treasury Officer Election Officer 1 ❑ Sub-Registrar Circle Officer Revenue Shristadar Office Assistant Other Grade IV Staff Working hours for office The working hours for all offices are from 1000 hrs to 1700 hrs with no break on all working days during the months from March to September and from 1000 hrs to 1615 hrs from the months of October to February. (Note: Applications/petitions under the Right to Information Act/Rules will be accepted during office hours on the working days only) Particulars of its Organization, Functions and Duties, Section 4(1)(b)(i) 1. Name & Address: Office of the Deputy Commissioner, Kamrup District, Amingaon. FUNCTIONS AND DUTIES ADMINISTRATIVE FUNCTIONS: The Office of the Deputy Commissioner acts as the Administrative Headquarter of the district and maintains constant co-ordination with all Government Department within the district for smooth functioning of the administrative machinery Under the existing purview of law, rules and procedure set and framed by the Govt. -

Template Service Profile for Indian Administrative Service (IAS)

Template Service Profile for Indian Administrative Service (IAS) Overview Indian Administrative Service (IAS) the premier service of Government of India was constituted in 1946. Prior to that Indian Imperial Service (1893-1946) was in force. As on 1.1.2013, sanctioned strength of IAS was 6217 comprising of 4313 posts to the filled by direct recruits and 1904 posts to be filled by promotion /appointment of State Civil Services officers/ Non-State Civil Service officers. The civil services have been a hallmark of governance in India. The Constitution provides that without depriving the States of their right to form their own Civil Services there shall be an All India service recruited on an All- India basis with common qualifications, with uniform scale of pay and the members of which alone could be appointed to these strategic posts throughout the Union." No wonder that Sardar Vallabhai Patel, one of the eminent leaders of the freedom struggle referred to the ICS as the steel frame of the country. The civil services, therefore, represents the essential spirit of our nation - unity in diversity. Recruitment At present there are three modes of recruitment to IAS viz (i) Through Civil Services Examination conducted by UPSC every year; (ii) Through promotion of State Civil Service officers to IAS; and (iii) Through selection of non - State Civil Service officers. Roughly 66(1/3%) posts are meant for Direct Recruitment and 33 (1/3%) posts are meant for promotion quota. Training Both Direct Recruit as well as promotee IAS officers are imparted probationary training at Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration (LBSNAA). -

District at a Glance 1 Chapter

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN KAMRUP METROPOLITAN DISTRICT DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHOURITY, KAMRUP METROPOLITAN DISTRICT DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1 CHAPTER 1.1. INTRODUCTION: The Present Assam was referred to as Kamrup in many of the ancient Indian literature. It was also known as Pragjyotishpur due to the astrology (Jyotish Shashtra) practices that prevailed in this part of the country during that time. However, "Kamrup" became a more predominant name in the later part of the history. There is a famous story which says the reason behind the naming of this place "Kamrup": Kamrup Metropolitan District is vulnerable to various hazards like flood, landslide, strom, riverbank erosion, urban flash food and water logging. Manmade disasters like fire incident (domestic and commercial), bombblast and road accident also occur time to time. Besides, the entire district falls under seismic zone V. In 1897 and 1950 two major earthquakes divested the region. Recently on 21st September 2009 an earthquake of magnitude 6.2 (epicenter in Bhutan) also affected many buildings in the Guwahati city. This plan focuses on mitigation, preparedness, and operations and defines the Characterization of responder agencies of the district, from within and outside the government. 1.2. DISTRICT PROFILE LOCATION: Kamrup metropolitan district is located between 25o43’and 26o51’ N Latitude and 90o36’ – 92o12’ E Longitude. AREA AND POPULATION: Area : 867.25 Sq. Km Population : 12,60,419 (as per 2011 Census) 1.3. ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS: • This district has one Sub-Divisions-Kamrup Metropolitan Sadar Sub-Division. • The Kamrup Metropolitan district has 6 (Six) Revenue Circles viz. Sonapur RC, Guwahati RC, Azara RC, North Guwahati RC, Chandrapur RC, Dispur RC. -

Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh District Majistrate Divisional Forest Officer (DFO) Ganga Vichar Manch Nehru Yuva Kendra Sangathan (NYKS) Name of District Youth Coordinator Mobile Number Landline number of Name of Districts Name of Districts District DM name and Address Telephone District DFO name and Address Mobile no. Name Region Location Mobile no. (DYC) of DYC Kendra 1 Bijnor 9454417570 Bijnor DFO Bijnor(SF) 9453006738 - 01342-262259 Mr. Chandraprakash Chauhan Coordinator-West UP Region Vidurkuti (Bijnore) 9310186745 Director General (over all) Major General Dilawar Singh 011-22446078 [email protected] 2 Muzaffarnagar 9454417574 Muzaffarnagar DFO Muzaffarnagar 9453006658; 0131-2621740 Mr. Raghavendra Singh Coordinator-Kanpur Region,U.P Kanpur,Bithpoor 7007887446 Joint Director (over all) Mr. M.P. Gupta 9811464258 3 Badaun 9415908422 Badaun DFO - Badaun 9453005543; 05832-266098 Ms. Anamika Chaudhary Coordinator-Kashi Region,U.P Allahabad 9415214619 Assistant director (over all) Mr. A.K. Verma 9818796097 Uttar Pradesh State sdnyksuttarpradesh@gm Shahjahanpur 9454417527 Shahjahanpur 4 Mr. Sanjeev Chaurasia Joint Coordinator-Kashi Region,U.P Varanasi 9334028085, 9721280988 Coordinator Shri JPS Negi 8005496699 ail.com 5 Aligarh 9454415313 Aligarh DFO Aligarh 9453006593; 0571-2720076 Mr. Rambahadur Singh Ganga Volunteer- Awadh Region UttarRajghat-Chibramau Pradesh Hardoi 9415175587 Bijnor Sh Sanjeev Kumar 9354980434 01342-255123 6 Hardoi 9454417556 Hardoi DFO Hardoi - Mr. Ashok Sharma Joint Coordinator-West U.P. Region Garhmukteshwar 9634755249;8979328472 Meerut Sh. Ashu Gupta 9027816253 0121-2771352 7 Unnao 9454417561 Unnao DFO-Unnao 9453008179;0515-2829274 Mr. Ashish Sharma Joint Coordinator-West U.P. Region Anupshahr, Narora, RoobhiBhagwanpur 9891971708 Bulandshahar Sh. Shiv Dev Sharma 9968030443 05732-282845 Kanpur Dehat Kanpur Dehat DFO Kanpur Dehat 9453006402; 05111-271553 Hapur (Gaziabad) Sh.