International Journal of Pedagogy Innovation and New Technologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanctoria, P.O. Dishergarh 713333 ” Within 10 Days from the Date of Publication of This Advertisement

Ref.no. HoD_IAD/NS_StoreAudit/EOI/2019/55 Dated 11.03.2019 INVITATION OF EXPRESSION OF INTEREST FOR APPOINTMENT OF STORE AUDITORS Eastern Coalfields Limited invites Expression of Interest [EOI] for empanelment of 4 nos. of practicing firms of Chartered Accountants /Cost Accountants for conducting “Physical verification of store and spares and Reconciliation of Store ledgers with Financial ledgers on annual basis” of all of its 24 nos. of Stores of Areas/Units/workshops and HQ located in the states of Jharkhand and West Bengal for the FY 2018-19. Eligible firms may send their EOI in prescribed format in a SEALED COVER through Hand delivery /Speed post or Courier services, so as to reach the office of “The HOD, Internal Audit Department, Eastern Coalfields Ltd., CMD Office, Technical Building, IInd Floor, Sanctoria, P.O. Dishergarh 713333 ” within 10 days from the date of publication of this advertisement. The prescribed format of EOI containing detailed terms & conditions can be downloaded from the website: www.easterncoal.nic.in . Date of Closing – 21/03/2019 (4.00 PM) Date of Opening EOI – 25/03/2019 (11.00 AM) Eastern Coalfields Ltd. Sanctoria EOI Document for Store Audit [1] EASTERN COALFIELDS LIMITED A. PROFILE OF THE AUDIT FIRM 1 (i) Name / Title of the Firm : (ii) Year of Establishment : (iii) Status of Firm (Proprietor/Partnership) : (iv) Details of Partners/Proprietor : 2 Registration no. of the Firm (Please enclose the copy of certificate of Registration issued by the institute of Chartered Accountants of India/Institute of Cost Accountants of India in evidence of informations at Sl.no 1&2.) 3 Name of Qualified Assistants with Membership No. -

Office of the Commissioner of Police Asansol – Durgapur

OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF POLICE ASANSOL – DURGAPUR C.P. Order No. 20 /18 Dated : 13 / 04 /18 In exercise of power conferred upon me u/s 112(2)/115/116/117 of motor vehicles Act.1988 vide notification no. 2827(A)-WT/3M-80/2002 dated 01.09.11 of Transport Department, I, Shri Laxmi Narayan Meena, IPS, Commissioner of Police, Asansol-Durgapur do hereby issue the restrictive orders on the roads under Asansol-Durgapur Police Commissionerate as hereunder, in the interest of public safety and also to prevent danger, obstruction, inconvenience to public in general, to impose speed limit restrictions for regulating the movement of vehicles at different parts of Asansol-Durgapur Police Commissionerate. Sl. Name of Speed (Extent Reason for Speed Name of the place Name of the road No. the TG Limit of road) Limit Barakar Hanuman Charai 1 30 km/hr. G.T. Road 1.5 KM Congested area to Barakar Check-post Barakar Hanuman Charai Populated area and 2 40 km/hr. G.T. Road 3.9 KM to Kulti College Road School Kulti Collage Road to Populatedarea and 3 50 km/hr. G.T. Road 2.2 KM IISCO Road School Congested area and Neamatpur New Road to 4 30 km/hr. G.T. Road 1.4 KM School, Bankand Neamatpur Ghari Masjid Bazar Neamapur Ghari Masjid to 5 40 km/hr G.T. Road 1.5 KM Populated area Bangabasi Hotel Neamatpur New Road to Niyamatpur – 6 50 km/hr. 4 KM Populated area Chowranghee More Runarayanpur Road Chowranghee More to Niyamatpur – 7 Kulti TG 50 km/hr. -

Environmental Statement in Form-V Cluster No. – 12

ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT IN FORM-V (Under Rule-14, Environmental (Protection) Rules, 1986) (2019-2020) FOR CLUSTER NO. – 12 (GROUP OF MINES) Pandaveswar, Sonepur Bazari, Jhanjra and Bankola Area Eastern Coalfields Limited Prepared at Regional Institute – I Central Mine Planning & Design Institute Ltd. (A Subsidiary of Coal India Ltd.) G. T. Road (West End) Asansol - 713 304 CMPDI ISO 9001:2015 Company Environmental Statement for Cluster No. – 12 (Group of Mines) for the year 2019-20 ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT FOR CLUSTER NO. – 12 (GROUP OF MINES) FOR THE YEAR: 2019-2020 CONTENTS SL NO. CHAPTER PARTICULARS PAGE NO. 1 CHAPTER-I INTRODUCTION 2 – 9 2 CHAPTER-II ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT FORM-V (PART A TO I) 10 – 25 LIST OF ANNEXURES ANNEXURE NO. PARTICULARS PAGE NO. I AMBIENT AIR QUALITY AND HEAVY METAL ANALYSIS 26 – 34 II NOISE LEVEL 35 – 36 III MINE AND GROUND WATER QUALITY REPORT 37 – 47 IV GROUNDWATER LEVEL 48 PLATES I LOCATION PLAN II PLAN SHOWING LOCATION OF MONITORING STATIONS 1 Environmental Statement for Cluster No. – 12 (Group of Mines) for the year 2019-20 CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION 1.1 GENESIS: The Gazette Notification vide G.S.R No. 329 (E) dated 13th March, 1992 and subsequently renamed to ‘Environmental Statement’ vide Ministry of Environment & Forests (MOEF), Govt. of India gazette notification No. G.S.R No. 386 (E) Dtd. 22nd April’93 reads as follows. “Every person carrying on an industry, operation or process requiring consent under section 25 of the Water Act, 1974 or under section 21 of the Air Act, 1981 or both or authorisation under the Hazardous Waste Rules, 1989 issued under the Environmental Protection Act, 1986 shall submit an Environmental Audit Report for the year ending 31st March in Form V to the concerned State Pollution Control Board on or before the 30th day of September every year.” In compliance with the above, the work of Environmental Statement for Cluster No. -

Eastern Coalfields Limited (A Subsidiary of Coal India Ltd.)

HALF YEARLY ENVIRONMENT CLEARANCE COMPLIANCE REPORT OF CLUSTER 11 J-11015/245/2011-IA.II(M) FOR THE PERIOD OF OCTOBER 2018 TO MARCH 2019 Eastern Coalfields Limited (A subsidiary of Coal India Ltd.) Half Yearly EC Compliance report in respect of mines Area (Cluster 11), ECL Period:- October 2018 to March 2019 Specific Conditions Condition no.(i) The Maximum production from the mine at any given time shall not exceed the limit as prescribed in the EC. Compliance Kenda - Complied S.No Name of Mines Peak EC Production from(Oct ’18 to Capacity March ’19) (MTPA) (MT) 1 Krishnanagar 0.05 Temporarily closed. (U/G) 2 Haripur Group 2.30 0.565458 of Mines A Haripur(U/G + 0.75 Haripur UG is Temporarily OC ) closed & OCP Not yet started. B CBI(U/G) 0.10 0.029889 C Chora 7,9 & 10 0.15 0.07793 pit(U/G) D Bonbahal OC 0.5 0.102754 Patch(OCP) E Shankarpur/CL 0.8 0.354885 Jambad OC Patch/Mine(52 Ha) 3 New Kenda 2.00 0.119282 Group of Mines A New Kenda (UG) 0.05 0.015802 B West Kenda OC 0.75 Not yet started. Patch/Mines C New Kenda OC 1.2 0.10348 mine(240 Ha) 4 Bahula Group of 0.45 0.146471 Mines A Lower 0.15 0.035949 Kenda(U/G) B Bahula (U/G) 0.25 0.085078 C CL Jambad 0.05 0.025444 (U/G) 5 Siduli(U/G +OC) 1.2 0.054887, OCP not yet started. -

Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Groundwater Potential Zoning In

Journal of Spatial Hydrology Volume 4 Article 5 2004 Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Groundwater Potential Zoning in and around Raniganj coal mining area, Bardhaman District, West Bengal – A GIS and Remote Sensing Approach Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/josh BYU ScholarsArchive Citation (2004) "Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Groundwater Potential Zoning in and around Raniganj coal mining area, Bardhaman District, West Bengal – A GIS and Remote Sensing Approach," Journal of Spatial Hydrology: Vol. 4 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/josh/vol4/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Spatial Hydrology by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of Spatial Hydrology Vol.4, No.2 Fall 2004 Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Groundwater Potential Zoning in and around Raniganj coal mining area, Bardhaman District, West Bengal – A GIS and Remote Sensing Approach P. K. Sikdar1, S. Chakraborty2, Enakshi Adhya1 and P.K. Paul2 1Department of Environment Management Indian Institute of Social Welfare and Business Management, Kolkata, India 2 Department of Mining and Geology B.E. College (A Deemed University), Howrah, India Abstract The Raniganj area has a long history of coal mining starting from 1744. This has resulted in major change in land use pattern and high groundwater abstraction leading to drinking water crisis especially during the premonsoon period. In the present study, land use /land cover conversions in Raniganj area from 1972 to 1998 and groundwater potential zoning for future groundwater development has been delineated using the techniques of Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System (GIS). -

ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT in FORM-V (Under Rule-14, Environmental Protection Rules, 1986)

ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT IN FORM-V (Under Rule-14, Environmental protection Rules, 1986) (2015-2016) FOR CLUSTER NO. – 12 (GROUP OF MINES) Pandaveswar, Sonepur Bazari, Jhanjra and Bankola Area Eastern Coalfields Limited Prepared at Regional Institute – I Central Mine Planning & Design Institute Ltd. (A Subsidiary of Coal India Ltd.) G. T. Road (West End) Asansol - 713 304 CMPDI ISO 9001:2008 Company Environmental Statement for Cluster No. – 12 for the year 2015-16 ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT FOR CLUSTER NO. – 12 (GROUP OF MINES) FOR THE YEAR: 2015-2016 CONTENTS SL NO. CHAPTER PARTICULARS PAGE NO. 1 CHAPTER-I INTRODUCTION 2 – 11 2 CHAPTER-II ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT FORM-V (PART A TO I) 12 – 29 LIST OF ANNEXURES ANNEXURE NO. PARTICULARS PAGE NO. I AMBIENT AIR QUALITY AND HEAVY METAL ANALYSIS 30 – 34 II NOISE LEVEL 35 – 40 III MINE AND GROUND WATER QUALITY REPORT 41 – 49 IV GROUNDWATER LEVEL 50 PLATES I LOCATION PLAN II PLAN SHOWING LOCATION OF MONITORING STATIONS 1 Environmental Statement for Cluster No. – 12 for the year 2015-16 CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION 1.1 GENESIS: The Gazette Notification vide G.S.R No. 329 (E) dated13th March, 1992 and subsequently renamed to ‘Environmental Statement’ vide Ministry of Environment & Forests (MOEF), Govt. of India gazette notification No. G.S.R No. 386 (E) Dtd.22nd April’93 reads as follows. “Every person carrying on an industry, operation or process requiring consent under section 25 of the Water Act, 1974 or under section 21 of the Air Act, 1981 or both or authorisation under the Hazardous Waste Rules, 1989 issued under the Environmental Protection Act, 1986 shall submit an Environmental Audit Report for the year ending 31st March in Form V to the concerned State Pollution Control Board on or before the 30th day of September every year.” In compliance with the above, the work of Environmental Statement for Cluster No. -

European Researcher. 2010

European Researcher. Series A, 2019, 10(1) EUROPEAN RESEARCHER Series A Has been issued since 2010. E-ISSN 2224-0136. 2019, 10(1). Issued 4 times a year EDITORIAL BOARD Magsumov Timur – Naberezhnye Chelny State Pedagogical University, Naberezhnye Chelny (Editor in Chief) Makarov Anatoliy – Kazan Federal University, Kazan, Russian Federation (Deputy Editor in Chief) Bazhanov Evgeny – Diplomatic Academy Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russian Federation Beckman Johan – University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Biryukov Pavel – Voronezh State University, Voronezh, Russian Federation Goswami Sribas – Serampore College, West Bengal, India Dogonadze Shota – Georgian Technical University, Tbilisi, Georgia Series A Krinko Evgeny – Southern Scientific Centre of RAS, Rostov-on-Don, Russian . Federation Malinauskas Romualdas – Lithuanian Academy of Physical Education, Kaunas, Lithuania Markwick Roger – School of Humanities and Social Science, the University of Newcastle, Australia Md Azree Othuman Mydin – Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia Müller Martin – University St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland Ojovan Michael – Imperial College London, UK Ransberger Maria – University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany The journal is registered by Federal Service for Supervision of Mass Media, Communications and Protection of Cultural Heritage (Russia). Registration Certificate EL № FS77-62396 14 July 2015. ESEARCHER R Journal is indexed by: Academic Index (USA), CCG-IBT BIBLIOTECA (Mexico), Galter Search Beta (USA), EBSCOhost Electronic Jornals Service (USA), Electronic Journals Index (USA), Electronic scientific library (Russia), ExLibris The bridge to knowledge (USA), Google scholar (USA), Index Copernicus (Poland), math-jobs.com (Switzerland), One Search (United Kingdom), OAJI (USA), Poudre River Public Library District (USA), ResearchBib (Japan), Research Gate (USA), The Medical Library of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (China). -

Student Details (2017-19)

Student Details (2017-19) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 SI. Name of the Father's Address Category Year of Result Percentage Contact No./ Admission Fee No. student Name (Gen/SC/ST/ Admission Mobile No. (Receipt No., admitted OBC/Others) Date&Amount 1 Alpana Garain Ajit Kumar Garain Kumardihi, Burdwan 8759555992 OBC-B 2017 30000 Moira Colliery, P.O- Moira, 2 Amit Nonia Upendra Nonia 8670323409 P.S- Andal, Dist- Burdwan SC 2017 30000 15A/1/24 Ground Floor, 3 Anindita Mukherjee Arup Mukherjee 9163952377 Sepco Township, Durgapur, Gen 2017 30000 NatajiBurdwan Lane, Salbagal, 4 Anita Kumari Gupta Murari Prasad Gupta 9641354971 Banachity, Durgapur Gen 2017 30000 Old Court HSCL 5 Anjali Nayak Tarani Nayak 9002626154 Colony,Durgapur.Burdwan Gen 2017 30000 72,West Apcar garden P.O- 6 Anjani Singh Sarvesh Singh 9933771424 Chelidauga, Gen 2017 30000 RamChandraAsansol,Burdwan 7 Anjana Kumari Kushwaha Brijmohan Kushwaha 7864819596 Dangal,Barakar, Burdwan OBC-B 2017 30000 Kaviguru Sarani, 60 FT. 8 Anuradha Thakur Ashok KumarThakur Road, Indraprastha Ismile, 8759210733 Asansol Gen 2017 30000 Vill - New Egara, Post- Egara, 9 Arindam Mondal Tarapada Mondal 9614635822 Raniganj, Burdwan SC 2017 30000 Vill+ Post- Bijpur, Jamuria , 10 Atasi Lata Maji Ashok Maji 8927209510 Burdwan SC 2017 30000 Vill+ Post- Bijpur, Jamuria , 11 Baisakhi Maji Sarat Ch. Maji 8535884885 Burdwan SC 2017 30000 Lachipur Colliery , Kajora 12 Bibek Singha Dulal Singha 9093674688 More, Burdwan Gen 2017 30000 13 Bumba Sadhu Late Ananta Sadhu Taltore, Jamuria, Burdwan Gen 2017 9749970076 30000 Vill+Post- -

List of Polling Station

List of Polling Station 1 Assembly Name with No. : Kulti (257) Sl. No. Part No. Polling Station with No. 1 1 Sabanpur F.P.School (1) 2 2 Barira F.P.School (N) (2) 3 3 Barira F.P.School (S) (3) 4 4 Laxmanpur F.P.School (4) 5 5 Chalbalpur F.P.School (Room-1) (5) 6 6 Dedi F.P.School (6) 7 7 Kultora F.P.School (W) (7) 8 8 Kultora F.P.School (E) (8) 9 9 Neamatpur Dharmasala Room No.1 (9) 10 10 Jamuna Debi Bidyamandir Nayapara Room no.1 (10) 11 11 Jamuna Debi Bidyamandir , Nayapara Room no.2 (11) 12 12 Neamatpur F.P.School (12) 13 13 Neamatpur F.P.School (New bldg) (13) 14 14 Neamatpur F.P.School (Middle) (14) 15 15 Adarsha Janata Primary School Bamundiha, Lithuria Rd, R-1 (15) 16 16 Adarsha Janata Primary School Bamundiha, Lithuria Rd, R-2 (16) 17 17 Jaladhi Kumari Debi High School (R-1) (17) 18 17 Jaladhi Kumari Debi High School (R-2) (17A) 19 18 Belrui N.G.R. Institution (18) 20 19 Islamia Girls Jr High School, Neamatpur (R-1) (19) 21 20 Islamia Girls Jr High School , Neamatpur(R-2) (20) 22 21 Neamatpur Dharmasala (R-3) (21A) 23 21 Neamatpur Dharmasala (R-2) (21) 24 22 Sitarampur National F.P.School (22) 25 23 Eastern Railway Tagore Institute Room No.1 (23) 26 24 Eastern Railway Tagore Institute Room No.2 (24) 27 25 Belrui N.G.R. Institution Room (North) No.2 (25) 28 26 Belrui N.G.R. -

Contact No. of Asansol-Durgapur Police Commissionerate

Contact No. of Asansol-Durgapur Police Commissionerate Sl Telephone Mobile Designation Name Office Address E Mail ID No. Number Number Office of the Commissioner of Police C.P, Asansol Shri Siddh Nath ADPC. 5 Evelyn Lodge G.T. Road 0341 1. 8116604444 [email protected] Durgapur Gupta IPS Kumarpur Asansol - 04 P.O.- Asansol P.S. - 2257260 Asansol South Pin.- 713304 Office of the Deputy Commissioner of Dy. C.P (HQ) Shri Arindam Dutta Police (H.Q) ADPC. 5 Evelyn Lodge G.T. 0341 2. 8116604411 [email protected] Asansol Durgapur Chowdhury, IPS Road Kumarpur Asansol - 04 P.O.- Asansol 2253727 P.S. - Asansol South Pin.- 713304 Office of the Addi Deputy Commissioner of Police (Central ) ADPC. Bhoot Bunglow, Addl. Dy. C.P, Shri Rakesh Singh, 0341 3. Court Road Near Asansol Police Line 8116604455 [email protected] Central ADPC WBPS 2252640 Asansol - 04 P.O.- Asansol P.S. - Asansol South Pin.- 713304 Office of the Addi Deputy Commissioner of Police ( East ) ADPC. Arabindo Aviniue ( Addl. Dy. C.P, East Shri Amitabha 0343 4. A- Zone ) Durgapur E.F. Line Durgapur - 8116604422 [email protected] ADPC Maiti, IPS 2562762 04 P.O. - A ZONE Durgapur P.S. - Durgapur Pin.- 713204 Office of the Addi Deputy Commissioner Addl. Dy. C.P, Shri Biswajit of Police ( West ) ADPC. 2 No Club Road 0341 8116604433 5. [email protected] West ADPC Mahato, WBPS near Galf Ground Kulti P.O.- Kulti P.S. - 2515025 9735000747 Kulti Pin.- 713343 Office of the Astt. Commissioner of Police Shri Subrata Deb, ( East ) ADPC. Arabindo Aviniue ( A- Zone 0343 6. -

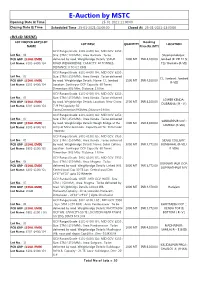

E-Auction by MSTC Opening Date & Time 25-01-2021::11:00:00 Closing Date & Time Scheduled Time 25-01-2021::13:00:00 Closed at 25-01-2021::13:00:00

E-Auction by MSTC Opening Date & Time 25-01-2021::11:00:00 Closing Date & Time Scheduled Time 25-01-2021::13:00:00 Closed At 25-01-2021::13:00:00 (ROAD MODE) LOT NO[PCB GRP]/LOT Booking LOT DESC QUANTITY LOCATION NAME Price(Rs./MT) GCV Range/Grade: 6101 -6400/ G4 ; MID GCV: 6250 ; Lot No. : 01 Size: STM (-100 MM) ; Area: Bankola . To be Shyamsunderpur:: PCB GRP :[ COAL EMD ] delivered by road. Weighbridge Details: SSPUR 1000 MT INR 4,100.00 Jambad (R-VIII T2 & Lot Name: ROAD WEIGHBRIDGE, CAPACITY: 60 TONNES, T1)/ Bankola (R-VII) 6101 -6400/ G4 DISTANCE: 0 TO 0.5 KMS GCV Range/Grade: 6101 -6400/ G4 ; MID GCV: 6250 ; Lot No. : 02 Size: STM (-250 MM) ; Area: Kenda . To be delivered C.L. Jambad:: Jambad PCB GRP :[ COAL EMD ] by road. Weighbridge Details: Name: C L Jambad 1500 MT INR 4,100.00 R-VIII Lot Name: Location: Sankarpur OCP Capacity: 60 Tones 6101 -6400/ G4 Dimention: 9X3 Mtrs. Distance: 1.8 Km. GCV Range/Grade: 6101 -6400/ G4 ; MID GCV: 6250 ; Lot No. : 03 Size: STM (-250 MM) ; Area: Kenda . To be delivered LOWER KENDA:: PCB GRP :[ COAL EMD ] by road. Weighbridge Details: Location: Near Chora 2500 MT INR 4,100.00 DOBRANA ( R - V ) Lot Name: 7 /9 Pit;Capacity: 50 6101 -6400/ G4 Tones;Dimention:9X3Mtrs.;Distance:0.8 Km. GCV Range/Grade: 6101 -6400/ G4 ; MID GCV: 6250 ; Lot No. : 04 Size: STM (-250 MM) ; Area: Kenda . To be delivered SANKARPUR OCP:: PCB GRP :[ COAL EMD ] by road. -

A New Gymnospermous Wood from Raniganj Coalfield, India

The Pa/aeobotanist, 26(3): 230-236, 1980. PALAEOSPIROXYLON - A NEW GYMNOSPERMOUS WOOD FROM RANIGANJ COALFIELD, INDIA M. N. V. PRASAD & SHAlLA CHANDRA BirbaI Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany, Lucknow-226 007, India ABSTRACT !,a/a.eospiroxy/oll ileterocel/u/aris gen. et sp. nov., collected from BonbahaI Colliery, Ra OlganJ Coalfield, West Bengal, India has been described. The salient features of. the wood are the presence of secretory cells in pith, endarch primary xylem, mIxed type of tracheid wall pitting and spiral thickenings in the secondary xylem. Key-words- Pa/aeospiroxy/oll, Gymllospermous wood, Upper Permian, Raniganj Coalfield (India). mmr ~RT*r ~~-~, 'lfmf ~ 'Z~ <r<ft;r3R"T'f~~- llTOliT ~ <n: 5ltIR ~ *m 'iRT ' ~ 'fi'n:rm-WR, ~ 'fi'n:rm-ffi;r, ~ <i<m1, mur ~ ~ ~~T• ~ ~~ 'f 0 5l;;rrRr q 'f 0 ;;rrRr 'fiT 'f1lFr fil;1;rr iTllf ~ I l'f'NfT it mcft ~T 'liT ~, ~ omr ~, fi:lfl!lQ 'fT~f.rI;T f'lTfu -m'f ~ ~ ~ it ~ ~ W 'liT'5OWT ifi mTT'f "f!\iUT ~ I INTRODUCTION xylem) from West Jamuria Colliery of the Raniganj Coalfield. In 1967, he also described Damudoxylon waltonii, Megaporo• have been described from Raniganj xylon krauselii and Trigonomyelon rani• SEVERAL fossil gymnospermous woods Coalfield by various authors Sahni, ganjense from West Jamuria Collier y, (1925 in Bradshaw); Sahni (1932); Fox, Raniganj Coalfield. (1934); Rao (1935); Maheshwari (1965,1967). However, so far no wood with secretory Shani (in Bradshaw, 1925) described a cells in the pith, endarch primary xylem, wood under the name Dadoxylon sp. from mixed type of tracheid pitting and spiral the Raniganj Coalfield near Asansol.