Cross-Modal Ownership in Passenger Transport – the British Experience Since 1985

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground

£5 when sold in paper format Available free by email upon application to: [email protected] An auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground Collectables Enamel signs & plates, maps, posters, badges, destination blinds, timetables, tickets & other relics th Saturday 25 February 2017 at 11.00 am (viewing from 9am) to be held at THE CROYDON PARK HOTEL (Windsor Suite) 7 Altyre Road, Croydon CR9 5AA (close to East Croydon rail and tram station) Live bidding online at www.the-saleroom.com (additional fee applies) TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Transport Auctions of London Ltd is hereinafter referred to as the Auctioneer and includes any person acting upon the Auctioneer's authority. 1. General Conditions of Sale a. All persons on the premises of, or at a venue hired or borrowed by, the Auctioneer are there at their own risk. b. Such persons shall have no claim against the Auctioneer in respect of any accident, injury or damage howsoever caused nor in respect of cancellation or postponement of the sale. c. The Auctioneer reserves the right of admission which will be by registration at the front desk. d. For security reasons, bags are not allowed in the viewing area and must be left at the front desk or cloakroom. e. Persons handling lots do so at their own risk and shall make good all loss or damage howsoever sustained, such estimate of cost to be assessed by the Auctioneer whose decision shall be final. 2. Catalogue a. The Auctioneer acts as agent only and shall not be responsible for any default on the part of a vendor or buyer. -

English Counties

ENGLISH COUNTIES See also the Links section for additional web sites for many areas UPDATED 23/09/21 Please email any comments regarding this page to: [email protected] TRAVELINE SITES FOR ENGLAND GB National Traveline: www.traveline.info More-detailed local options: Traveline for Greater London: www.tfl.gov.uk Traveline for the North East: https://websites.durham.gov.uk/traveline/traveline- plan-your-journey.html Traveline for the South West: www.travelinesw.com Traveline for the West & East Midlands: www.travelinemidlands.co.uk Black enquiry line numbers indicate a full timetable service; red numbers imply the facility is only for general information, including requesting timetables. Please note that all details shown regarding timetables, maps or other publicity, refer only to PRINTED material and not to any other publications that a county or council might be showing on its web site. ENGLAND BEDFORDSHIRE BEDFORD Borough Council No publications Public Transport Team, Transport Operations Borough Hall, Cauldwell Street, Bedford MK42 9AP Tel: 01234 228337 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] www.bedford.gov.uk/transport_and_streets/public_transport.aspx COUNTY ENQUIRY LINE: 01234 228337 (0800-1730 M-Th; 0800-1700 FO) PRINCIPAL OPERATORS & ENQUIRY LINES: Grant Palmer (01525 719719); Stagecoach East (01234 220030); Uno (01707 255764) CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE Council No publications Public Transport, Priory House, Monks Walk Chicksands, Shefford SG17 5TQ Tel: 0300 3008078 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] -

Combining Scheduled Commuter Services with Private Hire, Sightseeing and Tour Work: the London Experience by Derek Kenneth Robbins and Peter Royden White*

CEE INGS Twenty-sixth Annual Meeting Theme: "Markets and Management in an Era of Deregulation" November 13-15, 1985 Amelia Island Plantation Jacksonville, Florida Volume XXVI Number 1 1985 TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH FORUM In conjunction with CANADIAN TRANSPORTATION 4 RESEARCH FORM 273 Combining Scheduled Commuter Services with Private Hire, Sightseeing and Tour Work: The London Experience By Derek Kenneth Robbins and Peter Royden White* ABSTRACT dent operators ran only 8% of stage carriage mileage but operated 91% of private hire and contract The Transport Act 1980 completely removed mileage and 86% of all excursions and tours quantity control for scheduled express services mileage.' The 1980 Transport Act removed the which carry passengers more than 30 miles meas- quantity controls for two of the types of operation, ured in a straight line. It also made road service namely scheduled express services and most excur- licenses easier to obtain for operators wishing to run sions and tours. However the quality controls were services over shorter distances by limiting the scope retained, in the case of vehicle maintenance and for objections. As a result of these legislative inspections being strengthened. The Act redefined changes a new type of service has emerged over the "scheduled express" services. Since 1930 they had last four years carrying long-distance commuters to been defined by the minimum fare charged and and from work in London. Vehicles used on such because of inflation many short distance services services would only be utilised for short periods came to be defined as "Express", despite raising the every weekday unless other work were also found minimum fare yardstick in both 1971 and 1976. -

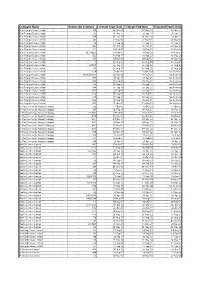

Operators Route Contracts

Company Name Routes On Contract Contract Start Date Contract End Date Extended Expiry Date Blue Triangle Buses Limited 300 06-Mar-10 07-Dec-18 03-Mar-17 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 193 01-Oct-11 28-Sep-18 28-Sep-18 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 364 01-Nov-14 01-Nov-19 29-Oct-21 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 147 07-May-16 07-May-21 05-May-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 376 17-Sep-16 17-Sep-21 15-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 346 01-Oct-16 01-Oct-21 29-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL3 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL1/NEL1 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL2 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 101 04-Mar-17 04-Mar-22 01-Mar-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 5 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 15/N15 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 115 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 674 17-Oct-15 16-Oct-20 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 649/650/651 02-Jan-16 01-Jan-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 687 30-Apr-16 30-Apr-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 608 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 646 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 648 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 652 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 656 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 679 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 686 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote -

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

View Fleet List (1919-2021)

FLEET LIST (1919-2021) Fleet Seating Into Fleet Reg No:Chassis: Make & Model Chassis No: Body: Make & Type New Withdrawn Notes No: & Format if used 1 PW 1558 Ford T Economy, Lowestoft B14F -/19 - 11/28 Burnt out 2 CT 6489 Chevrolet 29262 Andrews B14 05/24 - 11/28 Burnt out 3 CT 7421 Lancia 4947 Delaine 26 06/25 - 11/28 Burnt out 4 CT 8216 W&G. L 2553 W&G B26F 06/26 - 09/32 Broken up 01/36 5 CT 9025 W&G 3261 Hall Lewis B26F 05/27 - 06/36 Chassis to shed in yard, Broken Up : Body Broken up 06/39 6 CY 8972 W&G 5001 - 28 -/28 11/28 -/29 On loan from and returned to W&G 7 ? W&G - - 26 ? 11/28 -/29 On loan from operator near Cadnam : To W&G Southampton 8 ? Reo - - 26 ? 11/28 -/29 On loan from CH Skinner, Spalding (Dealer) 18 CT 9869 W&G 2639 Hall Lewis B32F 07/28 - 02/52 Broken up 11/55 9 TL 364 Gilford 166SD 10668 Clarke, Scunthorpe B26F 04/29 - by/40 To Canham, Whittlesey 10 TL 565 Chevrolet LQ 54366 Bracebridge B14F 06/29 - -/30 To Brown, Caister 19 TL 1066 Leyland TS2 60895 Duple C31F 03/30 - 03/55 Rebodied by Holbrook C37F in 1939. Scrapped on site 03/55 17 TL 1316 Reo Pullman 1528 Bracebridge B20F 07/30 - 12/48 To shed in Yard 11 TL 2224 Leyland TS4 202 Burlingham B32F 03/32 - 08/40 Requistioned by War Dept. Bombed in 1943 20 TL 2965 Leyland TS6 2982 Burlingham C37F 07/33 - 06/53 Requistioned by War Dept and returned. -

Review of Firstgroup Bus Undertakings in Bristol Provisional Decision

Review of FirstGroup bus undertakings in Bristol Provisional decision 9 June 2017 © Crown copyright 2017 You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Website: www.gov.uk/cma Members of the Competition and Markets Authority who are conducting this review Simon Polito (Chair of the Group) Anne Lambert Sarah Chambers Chief Executive of the Competition and Markets Authority Andrea Coscelli (acting Chief Executive) The Competition and Markets Authority has excluded from this published version of the provisional decision report information which the CMA considers should be excluded having regard to the three considerations set out in section 244 of the Enterprise Act 2002 (specified information: considerations relevant to disclosure). The omissions are indicated by []. Contents Page Summary .................................................................................................................... 2 Provisional decision .............................................................................................. 4 Provisional decision.................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction and background ............................................................................... -

Merger Control in the United Kingdom

MERGER CONTROL IN THE UNITED KINGDOM MERGER CONTROL IN THE UNITED KINGDOM By Dr Andrew Scott Senior Lecturer in Law, University of East Anglia Prof Morten Hviid Professor of Competition Law, University of East Anglia Prof Bruce Lyons Professor of Economics, University of East Anglia Mr Christopher Bright Partner, Shearman and Sterling LLP, London Consultant Editor 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Nicolas Squire, Kathleen Mealy, Joanna Broadbend The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) Crown copyright material is reproduced under Class Licence Number C01P0000148 with the permission of OPSI and the Queen’s Printer for Scotland First published 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. -

Bus Operators Finding Aid

Falkirk Archives (Archon Code: GB558) FALKIRK ARCHIVES Records of Businesses Bus Operators Finding Aid Walter Alexander & Sons Ltd Walter Alexander began running buses in the Falkirk area in 1914. The first Charabanc New Belhaven (convertible to lorry) arrived in the spring of 1913 and another Belhaven (second hand) also convertible to lorry, was acquired in either 1915 or 1916. During the First World War the company was limited to private hires and haulage and a service was run on Saturdays and Sundays between Falkirk and Bonnybridge. Another charabanc, a W.D. Leyland, was introduced to replace one of the Belhaven's in 1919. Walter Alexander took a private party to John O'Groats in the summer of 1919 and it is supposed to be the first charabanc to have arrived there. The company of W Alexander & Sons Ltd was formed in 1924. The routes expanded to include Stirling-Glasgow in 1925 and Perth - Glasgow in 1926. In 1927 the company acquired Elliott & Begg of Perth. In 1929 W Alexander & Sons were acquired as a subsidiary of SMT (The Scottish Motor Traction Co) and became the area company for most of the east of Scotland north of the Forth. Other bus companies acquired by SMT as subsidiaries to W Alexander & Sons included The Pitlochry Motor Co, Simpson's & Forresters (based in Fife) and the Scottish General Omnibus Group (based in Falkirk). The Scottish General Omnibus Group included Dunsire of Falkirk, the bus section of Wemyss Tramways, Penman of Bannockburn, the bus section of Dunfermline Tramways, the General Motor Carrying Co of Kirkcaldy and the Northern Omnibus Services of Elgin. -

2021 Book News Welcome to Our 2021 Book News

2021 Book News Welcome to our 2021 Book News. As we come towards the end of a very strange year we hope that you’ve managed to get this far relatively unscathed. It’s been a very challenging time for us all and we’re just relieved that, so far, we’re mostly all in one piece. While we were closed over lockdown, Mark took on the challenge of digitalising some of Venture’s back catalogue producing over 20 downloadable books of some of our most popular titles. Thanks to the kind donations of our customers we managed to raise over £3000 for The Christie which was then matched pound for pound by a very good friend taking the total to almost £7000. There is still time to donate and download these books, just click on the downloads page on our website for the full list. We’re still operating with reduced numbers in the building at any one time. We’ve re-organised our schedules for packers and office staff to enable us to get orders out as fast as we can, but we’re also relying on carriers and suppliers. Many of the publishers whose titles we stock are small societies or one-man operations so please be aware of the longer lead times when placing orders for Christmas presents. The last posting dates for Christmas are listed on page 63 along with all the updates in light of the current Covid situation and also the impending Brexit deadline. In particular, please note the change to our order and payment processing which was introduced on 1st July 2020. -

View Annual Report

National Express Group PLC Group National Express National Express Group PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2007 Annual Report and Accounts 2007 Making travel simpler... National Express Group PLC 7 Triton Square London NW1 3HG Tel: +44 (0) 8450 130130 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7506 4320 e-mail: [email protected] www.nationalexpressgroup.com 117 National Express Group PLC Annual Report & Accounts 2007 Glossary AGM Annual General Meeting Combined Code The Combined Code on Corporate Governance published by the Financial Reporting Council ...by CPI Consumer Price Index CR Corporate Responsibility The Company National Express Group PLC DfT Department for Transport working DNA The name for our leadership development strategy EBT Employee Benefit Trust EBITDA Normalised operating profit before depreciation and other non-cash items excluding discontinued operations as one EPS Earnings Per Share – The profit for the year attributable to shareholders, divided by the weighted average number of shares in issue, excluding those held by the Employee Benefit Trust and shares held in treasury which are treated as cancelled. EU European Union The Group The Company and its subsidiaries IFRIC International Financial Reporting Interpretations Committee IFRS International Financial Reporting Standards KPI Key Performance Indicator LTIP Long Term Incentive Plan NXEA National Express East Anglia NXEC National Express East Coast Normalised diluted earnings Earnings per share and excluding the profit or loss on sale of businesses, exceptional profit or loss on the -

On Stage Issue

The newsletter of Stagecoach Group Issue 110 | July 2015 STAGE ON page 2 page 6 INSIDE Memorial award | Greener together megabus.com continues European expansion megabus.com has revealed record advance ticket sales on its new network of domestic coach services in Italy as well as launching two new international routes. More than 30,000 customers purchased tickets during the first week of sales in Italy – higher than the initial sales on any of the company’s other networks in Europe. megabus.com services now link 13 destinations across Italy and passengers have been snapping up bargain fares from just €1 (plus 50 cents booking fee). The major new network of inter-city coach services covers Rome, Milan, Florence, Venice, Naples, Turin, Bologna, Verona, Padua, Siena, Genoa, Sarzana (La Spezia) and Pisa. megabus.com has also created around 100 new jobs through the opening of new bases near Milan megabus.com vehicles at the launch of the new Italian domestic network in Florence and in Florence. In addition, megabus.com recently launched its first base in France, where it has created 35 jobs between London and Milan via Lille, Paris, Lyon from customers has been fantastic. at a depot located near Lyon, from which a new and Turin. “The new routes between London and Milan, and international route now operates between megabus.com Managing Director Edward between Barcelona and Cologne are great news Barcelona, Perpignan, Montpellier, Avignon, Lyon, Hodgson said: “These latest routes mark even for our customers who now have access to even Mulhouse, Freiburg, Karlsruhe, Heidelberg, more expansion of our services in Europe.