Nate Schuett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

4Th Grade Music Vocabulary

4th Grade Music Vocabulary 1st Trimester: Rhythm Beat: the steady pulse in music. Note: a symbol used to indicate a musical tone and designated period of time. Whole Note: note that lasts four beats w Half Note: note that lasts two beats 1/2 of a whole note) h h ( Quarter Note: note that lasts one beat 1/4 of a whole note) qq ( Eighth Note: note that lasts half a beat 1/8 of a whole note) e e( A pair of eighth notes equals one beat ry ry Sixteenth Note: note that lasts one fourth of a beat - 1/16 of a whole note) s s ( A group of 4 sixteenth notes equals one beat dffg Rest: a symbol that is used to mark silence for a specific amount of time. Each note has a rest that corresponds to its name and how long it lasts: Q = 1 = q = 2 = h = 4 = w H W Rhythm: patterns of long and short sounds and silences. 2nd Trimester: Melody/Expressive Elements and Symbols Dynamics: the loudness and quietness of sound. Pianissimo (pp): very quiet or very soft. Piano (p ): quiet or soft. Mezzo Piano (mp): medium soft Mezzo Forte (mf): medium loud Forte (f ): loud/strong. Fortissimo (ff): very loud/strong Crescendo (cresc. <): indicates that the music should gradually get louder. Decrescendo (decresc. >): indicates that the music should gradually get quieter. Tempo: the pace or speed of the music Largo: very slow. Andante: walking speed Moderato: moderately, medium speed Allegro: quickly,fast Presto: very fast Melody: organized pitches and rhythm that make up a tune or song. -

1 an Important Component of Music Is the Rhythm, Or Duration of The

1 An important component of music is the rhythm, or duration of the sounds. We designate this with whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, eighth notes, etc., the names of which indicate the relative duration of notes (e.g., a half note lasts four times as long as an eighth note). ∼ 3 4 It isd of d courset t necessary to specify the actual (not just relative) duration of sounds. There are several ways to do this, we shall discuss two which reflect the manner in which music is displayed. Printed music groups notes into measures, and begins each line with a time signature which looks like a fraction, and specifies the number of notes in each measure. For example, the time signature 3/4 specifies that each measure contains three quarter notes (or six eighth notes, or a half note and a quarter note, or any collection of notes of equal total duration). (The above schematic is not divided into measures; a whole note would not fit within a measure in 3/4 time.) Indeed, you cannot tell from looking just at a measure whether the time signature is 3/4 or 6/8, but both the top and bottom of the time signature are important for specifying the nature of the rhythm. The top number specifies how many beats (or fundamental time units) there are in a measure, and the bottom number specifies which note represents the fundamental time unit. For example, 3/4 time specifies three beats to a measure with a quarter note representing one beat, 6/8 time specifies six beats to a measure with an eighth note representing one beat. -

Review of Musical Rhythm Symbols and Counting Rhythm Symbols Tell Us How Long a Note Will Be Held

Review of Musical Rhythm Symbols and Counting Rhythm symbols tell us how long a note will be held. Rhythm is measured in beats. This is our unit of measurement in music for rhythm. Some rhythms have a value that is greater than one beat. Here are some examples: Whole Note u The Whole Note is worth four beats of sound. It contains the counts 1, 2, 3, 4. 1 2 3 4 Half Note u The Half Note is worth two beats of sound. It contains the counts 1, 2. 1 2 Dotted Rhythms u The Dotted Half Note is equal to a half note note tied to a quarter note. It has the value of three beats. 3 2 1 u The Dotted Quarter Note is equal to a quarter note tied to an eighth note. It has the value of 1 ½ beats. 1 ½ 1 ½ Rhythms worth one beat: Quarter Note u The Quarter Note is worth one beat. u It has one sound on the beat. u It will have a number as its count. (1, 2, 3 or 4) 1 2 3 4 Rhythms worth one beat: Eighth Notes u Two Eighth Notes are worth one beat. u It has two sounds on the beat. u First note has the # on it. u Second note has + on it 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + Rhythms worth one beat: Sixteenth Notes u Four Sixteenth notes are worth one beat. u It has four sounds on the beat. u First note has the # on it. u Second note has “e” on it. -

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Synchronizing Sequencing Software to a Live Drummer

Andrew Robertson and Mark D. Plumbley Synchronizing Sequencing School of Electronic Engineering and Computer Science Queen Mary University of London Software to a Live Drummer Mile End Road London E1 4NS, UK {andrew.robertson, mark.plumbley} @eecs.qmul.ac.uk Abstract: This article presents a method of adjusting the tempo of a music software sequencer so that it remains synchronized with a drummer’s musical pulse. This allows music sequencer technology to be integrated into a band scenario without the compromise of using click tracks or triggering loops with a fixed tempo. Our design implements real-time mechanisms for both underlying tempo and phase adjustment using adaptable parameters that control its behavior. The aim is to create a system that responds to timing variations in the drummer’s playing but is also stable during passages of syncopation and fills. We present an evaluation of the system using a stochastic drum machine that incorporates a level of noise in the underlying tempo and phase of the beat. We measure synchronization error between the output of the system and the underlying pulse of the drum machine and contrast this with other real-time beat trackers. The software, B-Keeper, has been released as a Max for Live device, available online at www.b-keeper.org. Introduction and Motivation MIDI messages. Commercial sequencers include Ableton Live, Pro Tools, Logic Studio, Nuendo, and One challenge currently faced by rock and pop bands others. These programs provide an optional click is how to incorporate electronic and pre-recorded track when recording, thereby providing audible musical parts when playing live. -

The Guinness 500 Techniques, Examples & Glossary

“The Guinness 500” - Harp Techniques, Examples and Glossary - - “THE GUINNESS 500” - Techniques & Glossary A Bebop Blues in F for 500 Harps - Premiere at the World Harp Congress in Amsterdam - Summer 2008 Deborah Henson-Conant • www.HipHarp.com “The Guinness 500” is swing music -- which is different from classical music, although it uses some of the same techniques. I’ll explain some of the techniques here, and I’ll put others on my website, where I’ll also try to put some videos to help you see how to play this piece. The first two pages of this document have the most important information - and the rest is helpful, but not essential. If you have questions, you can email me at [email protected]. I’ll try to email you back as soon as I can, and I’ll try to post the answers at my website. Before you email me, see if I’ve already posted the answer online at my “Student” Page. Go to www.HipHarp.com > Galleries > Student Page ESSENTIAL TECHNIQUES HOW TO PLAY THE “SWING FEEL” When music like this is marked to be played in “Swing Feel” (see measure 0), you need to “swing” the eighth notes so the music sounds like it’s written in 2/8. Also, the second note of each eighth note pair is also generally a little lighter. So don’t play each note with exactly the same evenness of classical music -- this music bounces, or swings. HOW TO PLAY “BISBIGLIANDO” and “TREMOLO” In Italian,“Bisbigliando” means “whispering” and “tremolo” means “trembling”. -

Rhythmic Values (Learnmusictheory.Net)

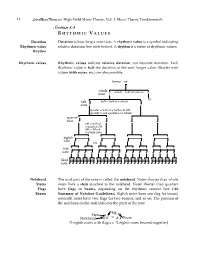

14 LearnMusicTheory.net High-Yield Music Theory, Vol. 1: Music Theory Fundamentals Section 1.4 R H Y T H M I C V ALUES Duration Duration is how long a note lasts. A rhythmic value is a symbol indicating Rhythmic value relative duration (see table below). A rhythm is a series of rhythmic values. Rhythm Rhythmic values Rhythmic values indicate relative duration, not absolute duration. Each rhythmic value is half the duration of the next longer value. Shorter note values (64th notes, etc.) are also possible. breve W whole whole = half of a breve note w w etc. half half = half of a whole note ˙ ˙ quarter = half of a half note OR quarter = one quarter of a whole quarter note œ 8th = half of œ œ œ a quarter OR 8th = 8th of a whole note eighth note œ œ etc. œ œ œ œ œ œ 16th note œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ 32nd note œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ Notehead The oval part of the note is called the notehead. Notes shorter than whole Stems notes have a stem attached to the notehead. Notes shorter than quarters Flags have flags or beams, depending on the rhythmic context (see 1.10 Beams Summary of Notation Guidelines). Eighth notes have one flag (or beam), sixteenth notes have two flags (or two beams), and so on. -

Violin Online Bowing Directions & Special Effects

VIOLIN BASICS EXERCISE ROOM LISTENING ROOM MUSIC STORE Violin Online Bowing Directions & Special Effects NOTATION NAME DEFINITION An accent placed over or under a note means the note should be emphasized by Accent playing forcefully. Play with the bow (bowing directions such as arco are often used after a plucked, Arco pizzicato section). Talon is French for frog, and this term means a particular section of music should Au talon be played with the bow at the frog (other terms for frog are nut or heel). Bariolage is a French term which means an “odd mixture of colors,” and directs the string player to achieve a contrast in tone colors by playing on different strings. An Bariolage example of barriolage is when the same note is played, alternating between open strings and stopped strings, or by playing a repeated passage, oscillating between two, three, or four strings. Fingering is often used to indicate bariolage. Bow lift Lift the bow, and return to its starting point. “With the wood.” Col legno means to strike the string with the stick of the bow rather than the hair (it is also called col legno battuto) When there are extended col legno passages in music, some professional violinists use inexpensive bows for these sections in order to avoid damaging their expensive bows. Col legno Col legno tratto is less commonly used, and indicates the wood of the bow should be drawn across the string (use with caution, this can damage the wood of the bow). Down Bow Begin the bow at the frog, and pull the bow from the frog to the tip. -

Lesson 3.2 – Ties, Slurs and Dotted Notes METHOD BOOK LEVEL 1D

METHOD BOOK Lesson 3.2 – Ties, Slurs and Dotted Notes Ties In music, a tie is a small curved line that joins together two notes of the same pitch. When this happens, the sound is held for the total value of all notes combined. Notice that the tie (the line itself) is always placed opposite to the direction of the note’s stem. Slurs In music, a slur is a small curved line that joins together two (or more) notes of a different pitch. When playing or singing notes joined by a slur, we move smoothly from one note to the next. As with ties, the line is placed opposite of the stem direction. LEVEL 1D | 1 METHOD BOOK Dotted Notes When we use a tie, we make the note longer. For example, if you tie a half note to a quarter note, you get 3 beats. Another way to make a note longer is to use a dotted note (by placing a dot in the space after the note). For example: In the first measure, a half note is tied to a quarter note, and in the second measure there is a dotted half note. Although they look different, they are the same length (3 beats)! Here is another example of how a dotted note can be used: When you put a dot after a note, you add half the length of the original note. For example, for a dotted half note you would add half of a half note (i.e. a quarter note) which equals 3 beats total. -

Music Theory 4 Rhythm Counting Second Chances Music Program

Music Theory 4 Rhythm Counting Second Chances Music Program Counting Eighth Note Triplets and Rests What is a Triplet? The term triplet refers to a series of three notes that are played in the space of two notes of the same value. For example, an eighth note triplet occurs when a musician is expected to play three eighth notes in the same amount of time as they would normally play two eighth notes. When written on the staff, the eighth note triplet will be notated by beaming three eighth notes together and placing a '3' above or below the middle note. The placement of the number 3 is dictated by the note’s stem direction. On occasion, composers and publishers will include a bracket along with the number ‘3’ in order to indicate a triplet rhythm. Although the use of these brackets may seem a bit unnecessary in the musical example above where there is a consistent series of eighth notes, the brackets can be very helpful when the triplet rhythms include both notes and rests. A triplet is the simplest incarnation of a tuplet. A tuplet occurs when a given number of notes of one type are spread equally over the same duration of a different number of notes of that same type. In this case, three eighth notes spread evenly over the space of two eighth notes. There are many other kinds of tuplets besides triplets, some of which are quite complex, but these are less common. Counting Eighth Note Triplets Just as there are many ways of counting rhythms in music, there are also multiple ways of counting eighth note triplets. -

Tuplets with Simple Entry

Tuplets with Simple Entry How to enter tuplets, particularly on the last beat of a measure, is a common question. As usual with Finale, there are a number of ways to do this. This is my preferred method, using Simple Entry and the QWERTY keyboard and number pad. If you are using a laptop without a numpad, you can activate a keyboard layout that will enable the right side of your keyboard to be used (Simple>Keyboard Shortcut Set>Laptop Shortcut Set). However, many users find it easier to purchase a USB number pad. We'll be using the number pad to select durations: 3=sixteenth note, 4=eighth note, 5=quarter note, and so forth. We'll enter the note by using the letter keys A-G. For a rest of the selected duration, use the 0 on the numpad. For the purpose of this tutorial, we'll assume that your default tuplet will be “3 eighth notes in the space of 2 eighth notes.” To set that up, specify an eighth note (numpad 4) and type any letter key A-G. Hit a B, for example. Next, hold the Alt key and type numpad 9. This will take you to the Tuplet definition box, where you can set up 3 eighths in 2, and check the Save as Default box. Hitting OK will return you to the score, where you will now see the eighth note, two eighth rests, and the triplet bracket. Entering two more notes, A and G, will complete the triplet. The next time you want to enter the same sort of triplet, enter your first note, and just type numpad 9.