An Economic Analysis of Massachusetts S. 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Featuring Nik Wallenda & “Grandma”

featuring Nik Wallenda & “Grandma” Welcome to the of 1 Welcome to the On behalf of all the performers, administrative staff, design team and crew, we welcome you to this very special production of the Big Apple Circus. This year marks the 40th Anniversary of a beloved New York City cultural gem that has delighted generations of families during its traditional holiday season at Lincoln Center and cities up and down the East Coast and as far west as Chicago. The 40th Anniversary celebrates the rebirth of a New York City and American cultural institution. After declaring bankruptcy in 2016, the Big Apple Circus seemed destined for extinction. Each of us in front and behind the curtain are honored to be part of this renaissance. The circus transcends all barriers bringing together children and adults of all ages, cultures and faith. For two hours, the world inside the Big Top transforms into a colorful kaleidoscope of wonder, amazement and laughter for all to of share. At the Big Apple Circus, we are committed to continuing the outreach programs so every child will have the opportunity to experience the wonder of the Circus. This year we will be expanding the number of shows adapted for children and young adults with Autism as well as those with hearing and visual challenges through our Circus of the Senses. In addition, we continue our commitment to provide children less fortunate the opportunity to attend the circus. Welcome back and enjoy the show. All of us at Big Apple Circus thank you for your support and hope you enjoy the magic and thrill of this special 40th Anniversary Show. -

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List – Updated July 1, 2021 The following AZA-accredited institutions have agreed to offer a 50% discount on admission to visiting Santa Barbara Zoo Members who present a current membership card and valid picture ID at the entrance. Please note: Each participating zoo or aquarium may treat membership categories, parking fees, guest privileges, and additional benefits differently. Reciprocation policies subject to change without notice. Please call to confirm before you visit. Iowa Rosamond Gifford Zoo at Burnet Park - Syracuse Alabama Blank Park Zoo - Des Moines Seneca Park Zoo – Rochester Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium - Staten Island Zoo - Staten Island Alaska Dubuque Trevor Zoo - Millbrook Alaska SeaLife Center - Seaward Kansas Utica Zoo - Utica Arizona The David Traylor Zoo of Emporia - Emporia North Carolina Phoenix Zoo - Phoenix Hutchinson Zoo - Hutchinson Greensboro Science Center - Greensboro Reid Park Zoo - Tucson Lee Richardson Zoo - Garden Museum of Life and Science - Durham Sea Life Arizona Aquarium - Tempe City N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher - Kure Beach Arkansas Rolling Hills Zoo - Salina N.C. Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores - Atlantic Beach Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Sedgwick County Zoo - Wichita N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island - Manteo California Sunset Zoo - Manhattan Topeka North Carolina Zoological Park - Asheboro Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoological Park - Topeka Western N.C. (WNC) Nature Center – Asheville Cabrillo Marine Aquarium -

THE BIG APPLE CIRCUS, LTD. Case No

16-13297-shl Doc 102 Filed 01/27/17 Entered 01/27/17 19:36:02 Main Document Pg 1 of 32 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In re: Chapter 11 THE BIG APPLE CIRCUS, LTD. Case No. 16-13297 (SHL) Debtor. GLOBAL NOTES AND STATEMENT OF LIMITATIONS, METHODOLOGY AND DISCLAIMER REGARDING DEBTOR’S SCHEDULES OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES AND STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL AFFAIRS On November 20, 2016 (the “Petition Date”), The Big Apple Circus, Ltd, the above- captioned debtor and debtor in possession (the “Debtor”) filed a voluntary petition for relief under chapter 11 of title 11 of United States Code (the “Bankruptcy Code”) with the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York (the “Bankruptcy Court”). The Debtor is currently operating its business as a debtor in possession pursuant to sections 1107(a) and 1108 of the Bankruptcy Code. The Debtor, with the assistance of its advisors, has prepared its Schedules of Assets and Liabilities (the “Schedules”) and Statement of Financial Affairs (the “SOFA”) pursuant to section 521 of the Bankruptcy Code and rule 1007 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure. These Global Notes and Statement of Limitations, Methodology and Disclaimer Regarding the Debtor’s Schedules of Assets and Liabilities and Statement of Financial Affairs (the “Global Notes”) pertain to all of the Schedules and the SOFA. While the Debtor’s management has made reasonable efforts to ensure that the Schedules and the SOFA are accurate and complete based on information that was available to them at the time of preparation, subsequent information or discovery may result in material changes to the Schedules and the SOFA, and inadvertent errors or omissions may exist in the Schedules and the SOFA. -

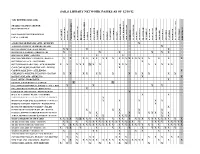

Sails Library Network Passes As of 12/10/12

SAILS LIBRARY NETWORK PASSES AS OF 12/10/12 *DECERTIFIED LIBRARIES SHADED COLUMNS ARE FOR RESIDENTS ONLY M PASS POLICIES DETERMINED BY SON BRIDGEWATER ATTLEBORO BRIDGEWATER . LOCAL LIBRARY * . BRIDGEWATER * * ATTLEBORO BERKLEY CARVER DARTMOUTH DIGHTON E EASTON FAIRHAVEN RIVER FALL FOXBORO FREETOWN HALIFAX HAN LAKEVILLE MANSFIELD MARION MATTAPOISETT MIDDLEBOROUGH BEDFORD NEW NORFOLK N NORTON PEMBROKE PLAINVILLE PLYMPTON RAYNHAM REHOBOTH ROCHESTER SEEKONK SOMERSET SWANSEA TAUNTON WAREHA W WESTPORT WRENTHAM ACUSHNET ALDEN HOUSE HISTORIC SITE - DUXBURY X AUDUBON SOCIETY OF RHODE ISLAND X BATTLE SHIP COVE - FALL RIVER X X X X BLITHWOLD GARDEN - BRISTOL, RI X X X X X X BOSTON BY FOOT - BOSTON X X BOSTON CHILDREN’S MUSEUM - BOSTON X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X BUTTERFLY PLACE - WESTFORD X BUTTONWOOD PARK ZOO - NEW BEDFORD X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X CAPE COD MUSEUM OF FINE ART - DENNIS X CAPRON PARK ZOO - ATTLEBORO X CHILDREN’S MUSEUM IN EASTON - EASTON X X X X X X X X X X X X X DAVIS FARMLAND - STERLING X X ECOTARIUM - WORCESTER X EDAVILLE RAILROAD - S. CARVER X X FALL RIVER HISTORICAL SOCIETY - FALL RIVER X X X X FULLER CRAFT MUSEUM - BROCKTON X GARDEN IN THE WOODS - FRAMINGHAM X HALL AT PATRIOT PLACE - FOXBORO X X HARVARD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY - CAMBRIDGE X HERITAGE MUSEUMS & GARDENS -SANDWICH X X X X X HIGGINS ARMORY MUSEUM - WORCESTER X HOUSE OF THE SEVEN GABLES - SALEM X INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ART - BOSTON X X X X X ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER MUSEUM - BOSTON X X X X X X X X X X JOHN F. -

Additional Member Benefits Reciprocity

Additional Member Benefits Columbus Member Advantage Offer Ends: December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted As a Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Member, you can now enjoy you can now enjoy Buy One, Get One Free admission to select Columbus museums and attractions through the Columbus Member Advantage program. No coupon is necessary. Simply show your valid Columbus Zoo Membership card each time you visit! Columbus Member Advantage partners for 2016 include: Columbus Museum of Art COSI Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens (Valid August 1 - October 31, 2016) King Arts Complex Ohio History Center & Ohio Village Wexner Center for the Arts Important Terms & Restrictions: Receive up to two free general admissions of equal or lesser value per visit when purchasing two regular-priced general admission tickets. Tickets must be purchased from the admissions area of the facility you are visiting. Cannot be combined with other discounts or offers. Not valid on prior purchases. No rain checks or refunds. Some restrictions may apply. Offer expires December 31, 2016 unless otherwise noted. Nationwide Insurance As a Zoo member, you can save on your auto insurance with a special member-only discount from Nationwide. Find out how much you can save today by clicking here. Reciprocity Columbus Zoo Members Columbus Zoo members receive discounted admission to the AZA accredited Zoos in the list below. Columbus Zoo members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. Each zoo maintains their own discount policies, and the Columbus Zoo strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo. -

2019 Zoo New England Reciprocal List

2019 Zoo New England Reciprocal List State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone Number CANADA Calgary - Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Stephenie Motyka 403-232-9312 Quebec – Granby Granby Zoo 50% Mireille Forand 450-372-9113 x2103 Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 416-392-9103 MEXICO Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon 50% David Rocha 52-477-210-2335 x102 Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Patty Pendleton 205-879-0409 x232 Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Shannon Wolf 907-224-6355 Every year, Zoo New England Arizona Phoenix The Phoenix Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 602-914-4365 participates in a reciprocal admission Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Membership Dept. 877-526-3960 program, which allows ZNE members Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 520-881-4753 free or discounted admission to other Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Kelli Enz 501-661-7218 zoos and aquariums with a valid California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 50% Becky Maxwell 805-461-5080 x2105 membership card. Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 50% Kathleen Juliano 707-441-4263 Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Katharine Alexander 559-498-5938 Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 323-644-4759 Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Sue Williams 510-632-9525 x150 This list is amended specifically for Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Elisa Escobar 760-346-5694 x2111 ZNE members. If you are a member Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Brenda Gonzalez 916-808-5888 of another institution and you wish to San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Jaz Cariola 415-623-5331 visit Franklin Park Zoo or Stone Zoo, San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% Nicole Silvestri 415-753-7097 please refer to your institution's San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo 50% Snthony Teschera 408-794-6444 reciprocal list. -

Appendix A: 1976 Clown College and 1977 Blue Unit Route

A p p e n d i x A : 1 9 7 6 C l o w n College and 1977 Blue Unit Route There’s nothing so dangerous as sitting still. You’ve only got one life, one youth, and you can let it slip through your fingers; nothing easier. Willa Cather, The Bohemian Girl CHAPTER 1 • ROMANCE OF THE RED NOSE Clown College, Ringling Arena, Venice, Sep.–Nov. 1976 CHAPTER 2 • BOWL OF CHERRIES Rehearsals and first performances, Ringling Arena, Venice, Jan. 10–Feb. 2 CHAPTER 3 • RUBBER NOSE MEETS THE ROAD Lakeland Civic Center, Feb. 4–6 Atlanta Omni, Feb. 9–20 Savannah Civic Center, Feb. 22–23 Asheville Civic Center, Feb. 25–27 Raleigh, Dorton Arena, Mar. 1–6 Fayetteville, Cumberland County Memorial Arena, Mar. 8–9 Columbia, Carolina Coliseum, Mar. 11–13 Charlotte Coliseum, Mar. 15–20 CHAPTER 4 • THE SHOW BUSINESS Knoxville, Civic Coliseum, Mar. 22–27 Cincinnati, Riverfront Coliseum, Mar. 30–Apr. 3 168 Appendix A Washington, DC, Armory, Apr. 6–17 Largo, Capital Centre, Apr. 20-May 1 CHAPTER 5 • LOVE ‘EM & LEAVE ‘EM Binghamton, Broome County Veterans Memorial Arena, May 4–8 Hartford, Civic Center, May 10–15 Portland, Cumberland County Civic Center, May 17–22 CHAPTER 6 • GOOD OL’ DAYS? Troy, RPI Field House, May 25–30 Providence Civic Center, June 1–5 Niagara Falls, International Convention Center, June 8–12 Wheeling Civic Center, June 15–19 Charleston Civic Center, June 21–22 Memphis, Mid-South Coliseum, June 24–26 CHAPTER 7 • RODEO ROUTE Little Rock, T.H. Barton Coliseum, June 28–29 Huntsville, von Braun Civic Center, July 1–4 Dallas, Convention Center, July 6–11 New Orleans, Superdome, July 14–17 Houston, Summit, July 20–31 Abilene, Taylor County Expo Center, August 2–3 Lubbock, Civic Center, August 5–7 CHAPTER 8 • SPIRIT OF ST. -

Additional Member Benefits Reciprocity

Additional Member Benefits Columbus Member Advantage Offer Ends: December 31, 2018 unless otherwise noted As a Columbus Zoo and Aquarium member, you can now enjoy you can now enjoy Buy One, Get One Free admission to select Columbus museums and attractions through the Columbus Member Advantage program. No coupon is necessary. Simply show your valid Columbus Zoo membership card each time you visit! Columbus Member Advantage partners for 2018 include: Columbus Museum of Art COSI Franklin Park Conservatory and Botanical Gardens Ohio History Center & Ohio Village Wexner Center for the Arts Important Terms & Restrictions: Receive up to two free general admissions of equal or lesser value per visit when purchasing two regular-priced general admission tickets. Tickets must be purchased from the admissions area of the facility you are visiting. Cannot be combined with other discounts or offers. Not valid on prior purchases. No rain checks or refunds. Some restrictions may apply. Offer expires December 31, 2018 unless otherwise noted. Fun Foto + Columbus Zoo members are invited to become Fun Foto + members. Have your picture taken by any of our roaming photographers and get all your photos taken during the in 2017 season digitally for $34.99! Nationwide Insurance As a Zoo member, you can save on your auto insurance with a special member-only discount from Nationwide. Find out how much you can save today by clicking here. Reciprocity Columbus Zoo Members Columbus Zoo members receive discounted or FREE admission to the AZA accredited Zoos in the list below. Columbus Zoo members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. -

A Conversation with Henry Kissinger Jaclyn Novatt

Issue 66 March 2010 A NEWSLETTER OF THE ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY COMMUNITY THE INSIGHT LECTURE BRINGS POlitiCS TO CAMPUS: A CONVERSAtiON WitH HENRY KISSINGER Jaclyn Novatt On Tuesday, January 19, Rockefeller University hosted Dr. Henry past, Kissinger spoke about the way sovereign nations are identi- Kissinger as the first speaker in a series of Insight Lectures dedi- fied. I thought this was a fascinating way of thinking. According cated to politics. If the emails back and forth over the university’s to Kissinger, today there are four worlds. There’s the post-modern political listserv are any indication, Dr. Kissinger is a highly po- Europe which, although the nations are sovereign, features more larizing figure. Kissinger served as National Security Advisor and cooperation than competition since the formation of the Euro- Secretary of State under President Richard Nixon, and continued pean Union. In the Asian world, nations see their neighbors as to advise subsequent administrations on foreign policy. As Sec- potential rivals and approach them with more caution. The Jiha- retary of State, Kissinger oversaw the negotiations of the Paris dist world does not rely on national boundary lines, but rather Peace Accords, ending the Vietnam War. He was also involved ideological and religious boundaries. Finally, there is the world in many controversial events, such as the bombings of Cambodia that exists irrespective of any boundaries: climate change, trade, and Laos in the early 1970s and the cia’s support of Chile’s Au- and nuclear proliferation. gusto Pinochet in 1973. Despite such controversy, Dr. Kissinger is After the formal conversation, the audience had the oppor- highly respected by many, winning the Nobel Peace Prize and the tunity to ask questions. -

Reciprocal Zoos & Aquariums

Reciprocal Zoos & Aquariums This list includes over 150 zoos and aquariums that current Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium members can visit at a reduced rate. Please contact the zoo or aquarium you are planning to visit in advance of your trip to confirm reciprocity and determine benefits. Remember to present your membership card and bring photo ID. Please note: - If you are a member of any zoo on the list below you can access Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium at a 50% discount of our general admission prices at the front gate. Please read the information at the bottom of this page before your visit. - PDZA membership reciprocity benefits DO NOT apply to Woodland Park Zoo and vice versa. - Reciprocity benefits are awarded to those individuals specifically named on your Zoo membership pass only. Guest passes and parking passes from reciprocal zoo memberships will not be honored. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA by State ALABAMA FLORIDA (cont) Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham St Augustine Alligator Farm – St. Augustine ALASKA The Florida Aquarium - Tampa Alaska Sealife Center - Seward West Palm Beach – Palm Beach Zoo ARIZONA Reid Park Zoo - Tucson ZooTampa at Lowry Park – Tampa Zoo Miami - Miami Phoenix Zoo – Phoenix GEORGIA SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium - Tempe Zoo Atlanta – Atlanta ARKANSAS IDAHO Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Idaho Falls Zoo at Tautphaus Park - Idaho Falls CALIFORNIA Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoo Boise – Boise Cabrillo Marine Aquarium – San Pedro ILLINOIS Charles Paddock Zoo - Atascadero Cosley Zoo – Wheaton CuriOdyssey - San Mateo -

Circus and the City New York, 1793–2010

Circus and the City New York, 1793–2010 Libsohn–Ehrenberg. “April Manhattan.” Cue, the Weekly Magazine of New York Life (April 1945), 16. On view September 21, 2012– February 3, 2013 Exhibition From September 21, 2012, to February 3, 2013, the Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Mate- rial Culture (BGC) will present Circus and the City: New York, 1793–2010, an exhibition that uses New York City as a lens through which to explore the extraordinary de- velopment and spectacular pageantry of the American circus. Through a wide variety of ephemera, images, and artifacts, the exhibition documents the history of the circus in the city, from the seminal equestrian displays of the late eighteenth century through the iconic late nineteenth-century American railroad circus to the Big Apple Circus of today. From humble beginnings, the circus grew into the most popular form of entertain- “Nixon & Co.’s Mammoth Circus: The Great Australian ment in the United States. By the turn of the twentieth Rider James Melville as He Appeared Before the Press of New York in His Opening Rehearsal at Niblo’s Garden,” century, New York City was its most important market 1859. Poster, printed by Sarony, Major, & Knapp, New and the place where cutting-edge circus performances York. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society. and exhibitions were introduced to the nation. “Circus and the City promises to be one of the grandest and it offers a compelling look at how New York City exhibitions about the American circus ever mounted, influenced and inspired this iconic form of American popular entertainment,” said curator Matthew Witt- mann, a curatorial fellow at the BGC. -

This Is the First Time I Ever Saw a Free Headstand with Part- He Perform

NEWSLETTER MARCH 1973 Vol No 3 This Newsletter is the official publication of the International Jugglers Association^ Editors» Ken and Carol Benge, 1551 Hillcrest Avenue, Hanover Park, 111® 60103. FROM GAY Wc NG The HAI CHAI VARIETY SHOW was here in Chinatown for 13 days, and will start another two weeks in Los Angeles from February 26th0 After that they v/ill be in New York for-tv/o weeks* The show cbtoges some of the acts every three to five days* They do have at least the total of 28 different acts, consisting o^ singing, dancing, acrobatics, juggling, high wire, balancing, magic .strong men, trapeze, etc* Some of the juggling tricks were done by a fellow juggling three fire torches* He starts by placing one lit fire torch on his forehead in a balance* He then juggles the three torches over the left and right shoulders, under both legs and then he showers them. A FREE H.EADSTAND is done with the sister being the bear er, and the younger_brother on top. What really got me is this is the first time I ever saw a free headstand with part- ener WITHOUT ANY HEAD GRUMF/.ET OR HEAD DOUGHNUT! They balance for well over five minutes doing the cha-cha-cha dance and then later on they light up a cigarette. They also do some ^ugp-ling and the brother on top spins some rings with his feet. A great act indeed* I am happy to say that I saw the show 3 times, Mr. Hai Ken Hsin, Captain of the team, invited me two of the times* I was talking to him in his room and I just mentioned could he perform the free headvStand also? He hopped right into it -right on the rug, no rings, *nothirig.