Air Embolism - a Case Series and Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venous Air Embolism, Result- Retrospective Study of Patients with Venous Or Arterial Ing in Prompt Hemodynamic Improvement

Ⅵ REVIEW ARTICLE David C. Warltier, M.D., Ph.D., Editor Anesthesiology 2007; 106:164–77 Copyright © 2006, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Diagnosis and Treatment of Vascular Air Embolism Marek A. Mirski, M.D., Ph.D.,* Abhijit Vijay Lele, M.D.,† Lunei Fitzsimmons, M.D.,† Thomas J. K. Toung, M.D.‡ exogenously delivered gas) from the operative field or This article has been selected for the Anesthesiology CME Program. After reading the article, go to http://www. other communication with the environment into the asahq.org/journal-cme to take the test and apply for Cate- venous or arterial vasculature, producing systemic ef- gory 1 credit. Complete instructions may be found in the fects. The true incidence of VAE may be never known, CME section at the back of this issue. much depending on the sensitivity of detection methods used during the procedure. In addition, many cases of Vascular air embolism is a potentially life-threatening event VAE are subclinical, resulting in no untoward outcome, that is now encountered routinely in the operating room and and thus go unreported. Historically, VAE is most often other patient care areas. The circumstances under which phy- associated with sitting position craniotomies (posterior sicians and nurses may encounter air embolism are no longer fossa). Although this surgical technique is a high-risk limited to neurosurgical procedures conducted in the “sitting procedure for air embolism, other recently described position” and occur in such diverse areas as the interventional radiology suite or laparoscopic surgical center. Advances in circumstances during both medical and surgical thera- monitoring devices coupled with an understanding of the peutics have further increased concern about this ad- pathophysiology of vascular air embolism will enable the phy- verse event. -

Pulmonary Embolism a Pulmonary Embolism Occurs When a Blood Clot Moves Through the Bloodstream and Becomes Lodged in a Blood Vessel in the Lungs

Pulmonary Embolism A pulmonary embolism occurs when a blood clot moves through the bloodstream and becomes lodged in a blood vessel in the lungs. This can make it hard for blood to pass through the lungs to get oxygen. Diagnosing a pulmonary embolism can be difficult because half of patients with a clot in the lungs have no symptoms. Others may experience shortness of breath, chest pain, dizziness, and possibly swelling in the legs. If you have a pulmonary embolism, you need medical treatment right away to prevent a blood clot from blocking blood flow to the lungs and heart. Your doctor can confirm the presence of a pulmonary embolism with CT angiography, or a ventilation perfusion (V/Q) lung scan. Treatment typically includes medications to thin the blood or placement of a filter to prevent the movement of additional blood clots to the lungs. Rarely, drugs are used to dissolve the clot or a catheter-based procedure is done to remove or treat the clot directly. What is a pulmonary embolism? Blood can change from a free flowing fluid to a semi-solid gel (called a blood clot or thrombus) in a process known as coagulation. Coagulation is a normal process and necessary to stop bleeding and retain blood within the body's vessels if they are cut or injured. However, in some situations blood can abnormally clot (called a thrombosis) within the vessels of the body. In a condition called deep vein thrombosis, clots form in the deep veins of the body, usually in the legs. A blood clot that breaks free and travels through a blood vessel is called an embolism. -

Pulmonary Embolism in the First Trimester of Pregnancy

Obstetrics & Gynecology International Journal Case Report Open Access Pulmonary embolism in the first trimester of pregnancy Summary Volume 11 Issue 1 - 2020 Pulmonary embolism in the first trimester of pregnancy without a known medical history Orfanoudaki Irene M is a very rare complication, which if it is misdiagnosed and left untreated leads to sudden Obstetric Gynecology, University of Crete, Greece pregnancy-related death. The sings and symptoms in this trimester are no specific. The causes for pulmonary embolism are multifactorial but in the first trimester of pregnancy, Correspondence: Orfanoudaki Irene M, Obstetric the most important causes are hereditary factors. Many times the pregnant woman ignores Gynecology, University of Crete, Greece, 22 Archiepiskopou her familiar hereditary history and her hemostatic system is progressively activated for the Makariou Str, 71202, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, Tel +30 hemostatic challenge of pregnancy and delivery. The hemostatic changes produce enhance 6945268822, +302810268822, Email coagulation and formation of micro-thrombi or thrombi and prompt diagnosis is crucial to prevent and treat pulmonary embolism saving the lives of a pregnant woman and her fetus. Received: January 19, 2020 | Published: January 28, 2020 Keywords: pregnancy, pulmonary embolism, mortality, diagnosis, risk factors, arterial blood gases, electrocardiogram, ventilation perfusion scan, computed tomography pulmonary angiogram, magnetic resonanance, compression ultrasonography, echocardiogram, D-dimers, troponin, brain -

Cerebral Air Embolism Following Removal of Central Venous Catheter

MILITARY MEDICINE, 174. 8:878. 2009 Cerebral Air Embolism Following Removal of Central Venous Catheter CPT Joel Brockmeyer, MC USA; CPT Todd Simon. MC USA; MAJ Jason Seery, MC USA; MAJ Eric Johnson, MC USA; COL Peter Armstrong, MC USA ABSTRACT Cerebral air embolism occurs very seldom as a complication of central venous catheterization. We report a 57-year-old female with cerebral air embolism secondary to removal of a central venous catheter (CVC). The patient was trealed with supportive measures and recovered well with minimal long-ienn injury. The preventit)n of airemboli.sm related to central venous catheterization is discussed. INTRODUCTION airway. No loss of pulse or changes in rhythm strip occurred Central venous catheters (CVCs) are used extensively in criti- during code procedures. Following the code and stabilization cally patients. They are cotnnionly placed tor heitiodynamic of the patient's airway, she was transferred to the Surgical iiioniioring. administration of medications, tran.svenous pac- Intensive Care Unit. ing, hemodialysis. and poor peripheral access. Complications Spiral computed tomography (CT) of the chest and com- can occur and are numerous. We describe a case of cerebral air puted tomography of the abdomen and pelvis were undertaken embolism in a ?7-year-old female as a complication ot central with enterai and intravenous contrast. No pulmonary embo- venous catheterization and the treatment course. Additionally, lism or air embolism was visualized on computed tomography we discuss methcxls to prevent air embolism related to central pulmonary angiography (CTPA) and no pathology wiis seen venous catheteri^ation. on CT of the abdomen and pelvis. -

Long-Term Outcome of Iatrogenic Gas Embolism Nicolas Genotelle Cendrine Chabbaut Anne Huon Alexis Tabah Je´Roˆme Aboab Sylvie Chevret Djillali Annane

Intensive Care Med DOI 10.1007/s00134-010-1821-9 ORIGINAL Jacques Bessereau Long-term outcome of iatrogenic gas embolism Nicolas Genotelle Cendrine Chabbaut Anne Huon Alexis Tabah Je´roˆme Aboab Sylvie Chevret Djillali Annane Received: 19 June 2009 Abstract Objective: To establish of 1-year mortality (OR = 4.39, 95% Accepted: 24 January 2010 the incidence and long-term progno- CI 1.46–12.20 and OR = 6.30, 1.71– sis of iatrogenic gas embolism. 23.21, respectively). Among ICU Ó Copyright jointly held by Springer and Methods: This was a prospective survivors, independent predictors of ESICM 2010 inception cohort. We included all 1-year mortality were age consecutive adults with proven iatro- (OR = 1.07, 1.01–1.14), Babinski genic gas embolism admitted to the sign (OR = 6.58, 1.14–38.20) and sole referral academic hyperbaric acute kidney failure (OR = 8.09, center in Paris. Treatment was stan- 1.28–51.21). Focal motor deficits dardized as one hyperbaric session at (OR = 12.78, 3.98–41.09) and 4 ATA for 15 min followed by two Babinski sign (OR = 6.76, 2.24– 45-min plateaus at 2.5 then 2 ATA. 20.33) on ICU admission, and dura- J. Bessereau Á N. Genotelle Á A. Huon Á Inspired fraction of oxygen was set at tion of mechanical ventilation of A. Tabah Á J. Aboab Á D. Annane ()) 100% during the entire dive. Primary 5 days or more (OR = 15.14, General Intensive Care Unit, Hyperbaric endpoint was 1-year mortality. All 2.92–78.52) were independent pre- Centre, Raymond Poincare´ Hospital patients had evaluation by a neurolo- dictors of long-term sequels. -

Pulmonary Embolism

Pulmonary Embolism Pulmonary Embolism (PE) is the blockage of one or more arteries in the lungs, ultimately eliminating the oxygen supply causing heart failure. This can take place when a blood clot from another area of the body, most often from the legs, breaks free, enters the blood stream and gets trapped in the lung's arteries. Once a clot is lodged in the artery of the lung, the tissue is then starved of fuel and may die (pulmonary infarct) or the blockage of blood flow may result in increased strain on the right side of the heart. It is estimated that approximately 600,000 patients suffer from pulmonary embolism each year in the US. Of these 600,000, 1/3 will die as a result. Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) is the most common precursor of pulmonary embolism. With early treatment of DVT, patients can reduce their chances of developing a life threatening pulmonary embolism to less than one percent. Early treatment with blood thinners is important to prevent a life-threatening pulmonary embolism, but does not treat the existing clot in the leg. Get more information on Deep Vein Thrombosis. Symptoms of PE Symptoms of pulmonary embolism can include shortness of breath; rapid pulse; sweating; sharp chest pain; bloody sputum (coughing up blood); and fainting. These symptoms are frequently nonspecific to pulmonary embolism and can mimic other cardiopulmonary events. Since pulmonary embolism can be life-threatening, if any of these symptoms are present please see your physician immediately. Treatments for PE Anticoagulation The first line of defense when treating pulmonary embolism is by using an anticoagulant. -

Status Epilepticus Due to Cerebral Air Embolism After the Valsalva Maneuver CASE REPORT

eISSN 2508-1349 J Neurocrit Care 2019;12(1):51-54 https://doi.org/10.18700/jnc.190075 Status epilepticus due to cerebral air embolism after the Valsalva maneuver CASE REPORT Hyun Ji Lyou, MD; Hye Jeong Lee, MD; Grace Yoojin Lee, MD; Received: March 11, 2019 Won-Joo Kim, MD, PhD Revised: May 3, 2019 Accepted: May 27, 2019 Department of Neurology, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea Corresponding Author: Won-Joo Kim, MD Department of Neurology, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, 211 Eonju-ro, Gangnam-gu, Seoul 06273, Republic of Korea Tel: +82-2-2019-3324 Fax: +82-2-3462-5904 E-mail: [email protected] Background: Cerebral air embolism is uncommon but potentially causes catastrophic events such as cardiac damage or even death. However, due to a low overall incidence, it may go undiagnosed. Case Report: A 56-year-old man with a medical history of right upper lobectomy due to lung cancer showed changes in mental status after the Valsalva maneuver, followed by status epilepticus during admission. Brain and chest computed tomography showed cerebral air embolism and accidental pneumothorax in the right major fissure. After antiepileptic drug infusion and oxygen therapy, he recov- ered completely. Conclusion: Since cerebral air embolism may result in fatal outcomes, it should be suspected in patients with sudden neurological de- terioration after routine medical procedures. Keywords: Status epilepticus; Embolism, air; Pneumothorax; Valsalva maneuver INTRODUCTION CASE REPORT Cerebral air embolism is a rare but potentially severe complication A 56-year-old man with a medical history of right upper lobectomy of iatrogenic procedures or destructive lung disease, possibly re- due to lung cancer presented to the emergency room with changes sulting in neurological disorders such as encephalopathy, stroke, or in mental status after the Valsalva maneuver during a pulmonary seizure. -

Hypercoagulability in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia With

Published online: 2019-09-26 Case Report Hypercoagulability in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia with epilepsy Josef Finsterer, Ernst Sehnal1 Departments of Neurological and 1Cardiology and Intensive Care Medicine, General Hospital Rudolfstiftung, Vienna, Austria, Europe ABSTRACT Recent data indicate that in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic teleangiectasia (HHT), low iron levels due to inadequate replacement after hemorrhagic iron losses are associated with elevated factor‑VIII plasma levels and consecutively increased risk of venous thrombo‑embolism. Here, we report a patient with HHT, low iron levels, elevated factor‑VIII, and recurrent venous thrombo‑embolism. A 64‑year‑old multimorbid Serbian gipsy was diagnosed with HHT at age 62 years. He had a history of recurrent epistaxis, teleangiectasias on the lips, renal and pulmonary arterio‑venous malformations, and a family history positive for HHT. He had experienced recurrent venous thrombosis (mesenteric vein thrombosis, portal venous thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis), insufficiently treated with phenprocoumon during 16 months and gastro‑intestinal bleeding. Blood tests revealed sideropenia and elevated plasma levels of coagulation factor‑VIII. His history was positive for diabetes, arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, cerebral abscess, recurrent ischemic stroke, recurrent ileus, peripheral arterial occluding disease, polyneuropathy, mild renal insufficiency, and epilepsy. Following recent findings, hypercoagulability was attributed to the sideropenia‑induced elevation -

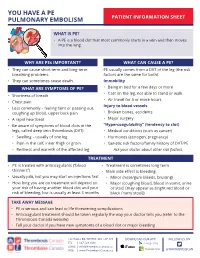

You Have a Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

YOU HAVE A PE PULMONARY EMBOLISM PATIENT INFORMATION SHEET WHAT IS PE? • A PE is a blood clot that most commonly starts in a vein and then moves into the lung. WHY ARE PEs IMPORTANT? WHAT CAN CAUSE A PE? • They can cause short term and long-term PE usually comes from a DVT of the leg (the risk breathing problems. factors are the same for both). • They can sometimes cause death. Immobility WHAT ARE SYMPTOMS OF PE? • Being in bed for a few days or more • Cast on the leg, not able to stand or walk • Shortness of breath • Air travel for 6 or more hours • Chest pain Injury to blood vessels • Less commonly – feeling faint or passing out, coughing up blood, upper back pain • Broken bones, accidents • A rapid heartbeat • Major surgery • Be aware of symptoms of blood clots in the “Hypercoagulability” (tendency to clot) legs, called deep vein thrombosis (DVT): • Medical conditions (such as cancer) • Swelling – usually of one leg • Hormones (estrogen, pregnancy) • Pain in the calf, inner thigh or groin • Genetic risk factors/family history of DVT/PE • Redness and warmth of the affected leg Ask your doctor about other risk factors. TREATMENT • PE is treated with anticoagulants (“blood • Treatment is sometimes long term thinners”) • Main side effect is bleeding: • Usually pills, but you may start on injections first • Minor (nose/gum bleeds, bruising) • How long you are on treatment will depend on • Major (coughing blood, blood in vomit, urine your risk of having another blood clot and your or stool [may appear as bright red blood or risk of bleeding, but is usually at least 3 months black / tarry stool]) TAKE AWAY MESSAGE • PE is serious and can lead to life threatening complications • Anticoagulant treatment should be taken regularly the way your doctor tells you (refer to the Thrombosis Canada website) • Tell your doctor if you have new symptoms of a blood clot or major bleeding 128 HALLS RD, WHITBY, ON, L1P 1Y8 DOWNLOAD OUR APP FOLLOW US ON TEL | 647-528-8586 EMAIL | [email protected] WEB | www.ThrombosisCanada.ca @THROMBOSISCAN. -

A REVIEW of CASES of PULMONARY BAROTRAUMA from DIVING EBH Lim, Jhow

A REVIEW OF CASES OF PULMONARY BAROTRAUMA FROM DIVING EBH Lim, JHow ABSTRACT Pulmonary barotrauma is a condition where lung injury arises from excessive pressure changes. Five cases of pulmonary barotrauma from diving have been seen at the Naval Medicine and Research Centre from 1970 to 1991. Four suffered surgical emphysema while one developed cerebral arterial gas embolism (CAGE). These cases are presented and discussed, including the predisposing factors, common signs and symptoms and essential treatment of this condition. Keywords: Pulmonary barotrauma, cerebral arterial gas embolism. SINGAPORE MED .I 1993; Vol 34: 16-19 INTRODUCTION CASE REPORTS Pulmonary barotrauma is a condition where lung injury occurs Case I as a result of excessive pressure changes. It arises because of HICK, aged 26, a naval seaman made a SCUBA dive on the the inverse relationship between the volume of a given mass of morning of 20 May 1976. His dive depth varied from 3 to 10 gas and its absolute pressure, representing a clinical sequelae metres. After an hour, he went to his reserve air and started to of Boyle's Law. surface. The excessive change in pressure has always been Immediately on surfacing, he felt a pain in the whole chest emphasized but it is the change in volume of the enclosed gas that was aggravated by deep breathing. On reaching shore, he that causes the tissue damage; it is also an individual's noticed a change in his voice and that his neck was swollen susceptibility to volume change that determines, whether one with a crackly feel to the skin. -

Therapeutic Hypothermia for Acute Air Embolic Stroke

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central CASE REPORT Therapeutic Hypothermia for Acute Air Embolic Stroke Matthew Chang, MD Maimonides Medical Center, Emergency Department, Brooklyn, New York John Marshall, MD Supervising Section Editor: Kurt R. Denninghoff, MD Submission history: Submitted October 19, 2010; Revision received March 21, 2011; Accepted April 11, 2011 Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2011.4.6659 [West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):111–113.] We describe a 65-year-old man who presented to the following vital signs: temperature of 99.48F, pulse of 86, emergency department with acute cerebral air embolism after respiratory rate of 18, and blood pressure of 120/91. The blood receiving computed tomography guided lung biopsy. The glucose obtained by finger stick was 149. The patient was patient presented with muscle strengths of 0/5 in left arm and hemodynamically stable, alert, speaking a few words in a 3/5 in left leg, aphasia, and a right pneumothorax. Our concern confused manner, and was not following simple commands. was to improve the patient’s neurological function, while Physical exam revealed bilateral breath sounds, with slightly ensuring stability in a patient who possibly had systemic air decreased breath sounds on the right and a right-sided pigtail embolism and a penumothorax, which is a contraindication to catheter visibly in place. On neurological exam, the patient was hyperbaric treatment. To that end, we treated the patient with noted to be flaccid in the left arm, with 0/5 in motor strength therapeutic hypothermia for 24 hours. -

Massive Air Embolism at the Initiation of Cardiopulmonary Bypass: Case Report

Tiirk Kardiyol Dem Arş 1996: 24: 538-539 Massive Air Embolism at the Initiation of Cardiopulmonary Bypass: Case report Nihan YAPICI, MD, Cem ALHAN, MD, Hüseyin MA ÇİKA, MD, Türkan KUDSİOGLU, MD, Zuhal A YKAÇ, MD Departmen/s of Anesthesiology and Cardiothoracic Surgery Siyami Ersek Thoracic and Cardioi'Gswlar Surgery Center. İstanbul. Turkey KARDiYOPULMONER BYPASS ÖNCESiNDE nary vcin. Suddcnly the hcart was distcndcd and hypotcn OLUŞAN MASiF HA VA EMBOLiSi: sion oecurcd. When wc want to initiatc CPB a large aıno OLGUSUNUMU unt of air was detcctcd in aortic eannula. Wc disconııccıcd the aortic cannula and rcal izcd that the lcf't heart was full Masif haı·a embolisi kardiyopulmoner bypass'a (KPB) gi of air. When wc wcrc tryi ng to purge the air from the hcart ren olgu/ann yaklaş1k %0.1-0.2'sinde oluşabilir. Bu has through the diseonncctcd aorıic cannula; the hcart fibrilla ta/ann yaklaş1k yansmda kallCI niiro/ojik hasar veya tcd. At this time bilateral pupillary dilatation oceurrcd, ho ölüm giiriilmektedir. Pe1jiizyon sistemine biiyiik miktar wcvcr as wc do not use EEG ınon i toring routinly, no data larda lıai'G çeşitli yollarla girebilir. Masif hava embolisi is available in rcgard of the c lcetrical activity of the brain. nin kalic1 hasarlanndan korunmak amaciyla derin lıipo The paticnt was brought to hcad-down position at about 20 termi ı •e serehral koruyucu ajanlar kullamlmaktaclir. KPB dcgrcc angle and the carotid artcrics wcrc coınprcsscd. His sirasuıda oluşan haı•a embolilerinin tedavisi için superior hcad and ncek wcrc surfacc coolcd. The aorıa was claın vena kava yoluyla retrograt serebral pe1ji'izyon kullanmu pcd and CPB initiatcd al'ıcr priming of aorıic cannula.