Law-Rights-Regulation Working-Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Model Code Casts Shadow on World Heritage Week Celebrations

2/7/2020 Model Code casts shadow on World Heritage Week celebrations Claim your 100 coins now ! Sign Up HOME PHOTOS INDIA ENTERTAINMENT SPORTS WORLD BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY LIFESTYLE Sexuality Happy Rose Valentine's Day 2020: Day 2020: From Share these Rose Day to WhatsApp Promise Day, messages, here's f... $S14M.99S, couplets wit$h10.1..9. 9 $99.99 NADA bans Indian$15.29 boxer Sumit San$gwan29.99 Propose Day 2020: Best This Valentine's Day, surprise your bae for a year for failing dope test WhatsApp messages, with 'pizza ring'; h... Diwali 2019: 5 DIY ways to use fairy lights SMS, couplets, quotes to Rose Day 2020: From Red to peach, here's for decoration this Diwali express... what colours of rose represen... TRENDING# Delhi Elections 2020 CAA protests Ind vs NZ Nirbhaya JNU Home » India » Ahmedabad Model Code casts shadow on World Heritage Week celebrations The civic body is taking steps on how to ensure that the week-long World Heritage Week celebration is a memorable one in wake of the Model Code of Conduct Bhadra Fort Bhadra Fort, which is a heritage site in the city The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation is all geared up to celebrate the World Heritage Week from November 19, the rst after it was declared as SHARE the rst World Heritage City of India by the UNESCO on July 8. However, AMC which had to shelve its plan to observe fortnight-long celebration beginning August 1 to showcase its achievement, in the wake WRITTEN BY of heavy rains and subsequent widespread oods across the state does n want to take any chances this time. -

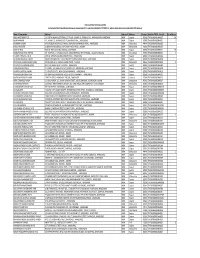

Developer Details

Developer Details Reg. No. Name Type Resident Address Office Address Mobile No. Reg. Date Validity Date Email ID DEV/00898 Zarna Developers Developer as above 5, Shiv Darshan 9825190196 28-Sep-2015 27-Sep-2020 [email protected] Sandipbhai B Kakadiya Bunglows, Opp. Shreeram DEV/00899 LAXMINARAYAN Developer 11, GIRIRAJ COLONY, 11, GIRIRAJ 9825034144 28-Sep-2015 27-Sep-2020 [email protected] INFRASRTUCUTRE PANCHVATI, COLONY, MANOJKUMAR AAMBAWADI, PANCHVATI, DEV/00900 Shrinand Buildcon Developer as above 1, S.F, Shreedhar 9825061073 16-Oct-2015 15-Oct-2020 [email protected] Jayantilal Nagjibhai Bunglows, Opp. Patel Grand Bhagwati, DEV/00901 SHREE SARJU Developer 9, Swagat Mahal, Near 9, Swagat Mahal, 9727442416 27-Oct-2015 26-Oct-2020 [email protected] BUILDERS Matrushree Party Plot, Near Matrushree CHANDRESHKUMAR Chandkheda , Party Plot, DEV/00902 PATEL DHIREN Developer B-6, MILAP B-6, MILAP 7096638633 03-Nov-2015 02-Nov-2020 [email protected] PRAHLADBHAI APPARTMENT, OPP. APPARTMENT, RANAKPUR SOC, OPP. RANAKPUR DEV/00903 SATASIYA Developer 14, SUROHI PARK 14, SUROHI PARK 9898088520 05-Nov-2015 04-Nov-2020 [email protected] PRAKASHBHAI PART-2,OPP.SUKAN PART-2, KARSHANBHAI BUNGLOWS AUDA T.P OPP.SUKAN DEV/00904 KARNAVATI Developer 17/A, KAMLA SOC, 17/A, KAMLA SOC, 9824015660 24-Nov-2015 23-Nov-2020 [email protected] BUILDERS RAMANI STADIUM ROAD, STADIUM ROAD, BHISHAM J NAVRANGPURA, NAVRANGPURA, DEV/00905 PATEL Developer F/101, SANGATH F/101, SANGATH 9925018327 01-Dec-2015 30-Nov-2020 [email protected] MALAYKUMAR SILVER, B/H D MART SILVER, B/H D BHARATBHAI MALL MOTERA, MART MALL DEV/00906 Harikrupa Developers Developer As Above 6, Ishan Park 7874377897 11-Dec-2015 10-Dec-2020 [email protected] Prajapati Jaymesh Society, Nr. -

Behrouz Biryani

Online Offer – Behrouz Biryani: • G 42, Shree Mahalaxmi Shops, Rudra Square, Bodakdev, Ahmedabad • 25, Rivera Arcade, Near Prahlad Nagar Garden, Prahlad Nagar, Ahmedabad • 2, IM Complex, Vastrapur Lake, Vastrapur, Ahmedabad • G/F 1, Animesh Complex, Panchavati Ellis Bridge, Near Chandra Colony, C G Road, Ahmedabad • 14, Ground Floor, Vitthal the Mall, Near Swagat Status, Chandkheda • C-19-20 Swagat Rainforest 2, Village Kudasan, Ta and District, Airport Gandhinagar Highway, Gandhinagar, Ahmedabad • 7th Cross Road, 8th Main, BTM Layout, Bangalore • Near Sony World Signal, Koramangala 6th Block, Bangalore • Kodichikkanahalli Main Road, Begur Hobli, Bommanahalli, Bangalore • Ground Floor, Actove Hotel, Kadubisanahalli, Marathahalli, Bangalore • Food Court, Sjr I-Park, Built In, Whitefield, Bangalore • Old Airport Road, Old Airport Road, Bangalore • Devatha Plaza, Residency Road, Bangalore • 123, Kamala Complex, AECS Layout, ITPL Main Road, Whitefield, Bangalore • 2318, Sector 1, Near NIFT College, HSR Layout, Bangalore • Kaggadaspura, CV Raman Nagar, Bangalore • Shop A-94 6/2, Opposite State Bank of India, 2nd Phase, J P Nagar, Bangalore • 101, Ground Floor, Manjunatha Complec, 22nd Main Road, 2nd Stage, Banashankari, Bangalore • Site No 8, New No 1, Channasandra, Property No 121, 2nd Main Road, Kr Puram Hobli, Kasturi Nagar, Bangalore • Shop 10-11, Electronic City Phase-1, 2nd Cross Road, Near Infosys Gate 1, Bangalore • 2283, 1st Main Road, Sahakar Nagar D Block, Bangalore • 3, 1st Floor, Apple City, Kadugodi Hoskote, Main Road, Seegehalli, Bangalore • Shop No. 837, BEML 3rd Stage, Halagevaderahalli, Rajarajeshwari Nagar, Bangalore • Dodaballapur Main Road, Puttenahalli, Yelahanka, Bangalore • Colony Skylineapartment, Canara Bank, Chandra Layout, Bangalore • Shop No. 90, First Floor, Sanjay Nagar Main Road, Geddalahalli, Bangalore • 6, First Floor, 9 Cross, 2nd Main, Binnamangala, 1st Stage, Indiranagar, Bangalore • Shop No. -

Marda Collections

Brand City Address (Marda Collections) UGF , M.L Plaza , Post Office, Chowmuhani, Mantribari Rd Ext, GLOBAL DESI Agartala Dhaleshwar, Agartala, Tripura 799001 And Designs - Gulmohar Park, G - 10, Ground Floor, Near Fun Republic, Satellite Road, AND Ahmedabad Ahmedabad - 380 00 K L Fashions - (And), Unit No. F - 23, First Floor, Alpha One Mall, Tpn. 1, Fp No. 261, AND Ahmedabad Vastrapur Lake, Ahmedabad Shop No. G11, Ground Floor, Gulmohar Park Mall, Near Fun re Public, Satellite Road, GLOBAL DESI Ahmedabad Ahmedabad - 380 GLOBAL DESI Ahmedabad 28, First Floor, Alpha One, Vastrapur Lake. Ahmedabad - 380054 AND+GLOBAL DESI Ahmedabad Shoppers Plaza, Nr. Peter England, CG Road, Ahmedabad - 380009 Shop No. 3, Ground Floor, Venus Atlantis, 100 Ft, Prahladnagar Road, Satellite, AND+GLOBAL DESI Ahmedabad Ahmedabad – 380015, Gujarat. GLOBAL DESI Aligarh Shop No 1, Ayodhya Kutti, Opposite Abdullah College,Marris Road, Aligarh - 202001 Abacus Retail, Shop No 81/32, Lal Bahadur Shastri Nagar, Civil Lines, Allahabad, Uttar AND+GLOBAL DESI Allahabad Pradesh - 211001 Unit No.21, UGF, B Wing, Trilium Mall, Circular Road, Basant Avenue, Amritsar, Punjab - AND Amritsar 143001 Ground Floor, Raghuvir City Centre, Bhalej Rd, Gamdi Vad, Sardar Ganj Anand, Gujarat AND+GLOBAL DESI Anand 388001 Ground 2: G2 - 15, Inorbit Mall, Whitefield, No. 75, EPIP Area, Whitefield, Bengaluru AND Bangalore 560066. Shop No. 209, Second Floor, Garuda Mall, Commissariat Road, Magrath Road Junction, AND Bangalore Bengaluru - 560025. AND Bangalore The High Street, 11th Main Road, 4th Block, Jayanagar, Bangalore - 560 011 Plot No. 11B, Survey No. 40/9, Dyvasandra Village, Krishna Raj Puram, Hobli, Bangalore AND Bangalore East Taluk, Bangalore - 560 048 Unit No. -

Ecological Investigations of Shahwadi Wetland Nainesh R

Explorer Research Article [Modi et al. , 4(12): Dec., 2013] CODEN (USA): IJPLCP ISSN: 0976-7126 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES Ecological investigations of Shahwadi Wetland Nainesh R. Modi 1*, Nilesh R. Mulia 1 and Sumesh N. Dudani 2 1, Department of Botany, M. G. Science Institute, Ahmedabad, (Gujarat) - India 2, Deparment of Botany, Yuvaraja’s College, University of Mysore, Mysore - India Abstract The wetlands form important repositories of aquatic biodiversity. The diverse ecoclimatic regimes extant in the country resulted in a variety of wetland systems ranging from high altitude cold desert wetlands to hot and humid wetlands in coastal zones with its diverse flora and fauna. There are many important lakes and wetlands in Ahmedabad including Kankaria lake and Vastrapur Lake. The Nalsarovar wetland and Thol lake in the outskirts of Ahmedabad city are very important spots for migratory birds coming from different parts of the world and hence, attracts large number of tourists. However, many small and big wetlands are also present in and around the city which has not received due attention and hence, have suffered badly in the increased age of industrialization and urbanization. One such wetland is Shahwadi wetland which is situated in the heavily industrialized Narol area of Ahmedabad city. This study was undertaken to understand the ecological richness and importance of this region and highlight its degrading condition. It was found that this wetland harbors a good number of migratory birds and local birds, but is in highly degrading condition due to the negligence of local people residing in the periphery and the industries running nearby. -

The Spectre of SARS-Cov-2 in the Ambient Urban Natural Water in Ahmedabad and Guwahati: a Tale of Two Cities

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.12.21258829; this version posted June 16, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . The Spectre of SARS-CoV-2 in the Ambient Urban Natural Water in Ahmedabad and Guwahati: A Tale of Two Cities Manish Kumar1,2*, Payal Mazumder3, Jyoti Prakash Deka4, Vaibhav Srivastava1, Chandan Mahanta5, Ritusmita Goswami6, Shilangi Gupta7, Madhvi Joshi7, AL. Ramanathan8 1Discipline of Earth Science, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 355, India 2Kiran C Patel Centre for Sustainable Development, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India 3Centre for the Environment, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam 781039, India 4Discipline of Environmental Sciences, Gauhati Commerce College, Guwahati, Assam 781021, India 5Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam 781039, India 6Tata Institute of Social Science, Guwahati, Assam 781012, India 7Gujarat Biotechnology Research Centre (GBRC), Sector- 11, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 011, India 8School of Environmental Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 110067, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected]; [email protected] Manish Kumar | Ph.D, FRSC, JSPS, WARI+91 863-814-7602 | Discipline of Earth Science | IIT Gandhinagar | India 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.12.21258829; this version posted June 16, 2021. -

State Zone Commissionerate Name Division Name Range Name

Commissionerate State Zone Division Name Range Name Range Jurisdiction Name Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range I On the northern side the jurisdiction extends upto and inclusive of Ajaji-ni-Canal, Khodani Muvadi, Ringlu-ni-Muvadi and Badodara Village of Daskroi Taluka. It extends Undrel, Bhavda, Bakrol-Bujrang, Susserny, Ketrod, Vastral, Vadod of Daskroi Taluka and including the area to the south of Ahmedabad-Zalod Highway. On southern side it extends upto Gomtipur Jhulta Minars, Rasta Amraiwadi road from its intersection with Narol-Naroda Highway towards east. On the western side it extend upto Gomtipur road, Sukhramnagar road except Gomtipur area including textile mills viz. Ahmedabad New Cotton Mills, Mihir Textiles, Ashima Denims & Bharat Suryodaya(closed). Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range II On the northern side of this range extends upto the road from Udyognagar Post Office to Viratnagar (excluding Viratnagar) Narol-Naroda Highway (Soni ni Chawl) upto Mehta Petrol Pump at Rakhial Odhav Road. From Malaksaban Stadium and railway crossing Lal Bahadur Shashtri Marg upto Mehta Petrol Pump on Rakhial-Odhav. On the eastern side it extends from Mehta Petrol Pump to opposite of Sukhramnagar at Khandubhai Desai Marg. On Southern side it excludes upto Narol-Naroda Highway from its crossing by Odhav Road to Rajdeep Society. On the southern side it extends upto kulcha road from Rajdeep Society to Nagarvel Hanuman upto Gomtipur Road(excluding Gomtipur Village) from opposite side of Khandubhai Marg. Jurisdiction of this range including seven Mills viz. Anil Synthetics, New Rajpur Mills, Monogram Mills, Vivekananda Mill, Soma Textile Mills, Ajit Mills and Marsdan Spinning Mills. -

Special Report on Ahmedabad City, Part XA

PRG. 32A(N) Ordy. 700 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PAR T X-A (i) SPECIAL REPORT ON AHMEDABAD CITY R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PRICE Rs. 9.75 P. or 22 Sh. 9 d. or $ U.S. 3.51 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: * I-A(i) General Report * I-A(ii)a " * I-A(ii)b " * I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :\< I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey .\< I-C Subsidiary Tables -'" II-A General Population Tables * II-B(l) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) * II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) * II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :l< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) * IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments * IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables :\< V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) ** VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Selected Crafts of Gujarat * VII-B Fairs and Festivals * VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration " ~ N ~r£br Sale - :,:. _ _/ * VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation ) :\' IX Atlas Volume X-A Special Report on Cities * X-B Special Tables on Cities and Block Directory '" X-C Special Migrant Tables for Ahmedabad City STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS * 17 District Census Handbooks in English * 17 District Census Handbooks in Gl~arati " Published ** Village Survey Monographs for SC\-Cu villages, Pachhatardi, Magdalla, Bhirandiara, Bamanbore, Tavadia, Isanpur and Ghclllvi published ~ Monographs on Agate Industry of Cam bay, Wood-carving of Gujarat, Patara Making at Bhavnagar, Ivory work of i\1ahllva, Padlock .i\Iaking at Sarva, Seellc l\hking of S,v,,,-kundb, Perfumery at Palanpur and Crochet work of Jamnagar published - ------------------- -_-- PRINTED BY JIVANJI D. -

Statement of Unclaimed Dividend Amount Consecutively for 7 Years from Dividend of FY 2010-11, Whose Shares Are to Be Transferred to IEPF Account

THE ANUP ENGINEERING LIMITED Statement of Unclaimed Dividend amount consecutively for 7 years from Dividend of FY 2010-11, whose shares are to be transferred to IEPF Account Name of Shareholder Address-1 Address-2 Address-3 Pincode Folio No / DP ID - Client ID No. of Shares AEGIS INVESTMENTS LTD C/O.SHETH LALBHAI DALPATBHAI, 1ST FLOOR, 'AKSHAY' 53, SHRIMALI SOC., NAVRANGPURA, AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380009 THEA0000000000A00179 306 ANJANA MANAN 101, AKSHAY, 53, SHRIMALI SOCIETY, NAVRANGPURA,, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380009 THEA0000000000A00217 11 ARJANBHAI ALABHAI 664 KUBERDAS MODI'S OLD CHAWAL, SAIJPUR BOGHA NARODA ROAD, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Maharashtra 444444 THEA0000000000A00203 1 BAKULA R JHAVERI 10 SEKHSARIA BUILDINGS, 2ND FLOOR, 448 SVP ROAD, , MUMBAI INDIA Maharashtra 400004 THEA0000000000B00168 1 BANK OF INDIA BANK OF INDIA BUILDING, BHADRA, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380001 THEA0000000000B00118 783 BHARATKUMAR SHIVJI SHETHIA 7/1 'TILOTTMA', 1-C PANKAJ MULLICK, SARANI (FORMALY RITCHIE ROAD), , CALCUTTA KOLKATA INDIA West Bengal 700019 THEA0000000000B00138 33 C V MEHTA PRIVATE LIMITED BANK OF BARODA BUILDING, GANDHI ROAD, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380001 THEA0000000000C00068 1 DR ARUNA RAMANLAL JHAVERI RAJAN SHRI NIWAS SOC., SUKHIPURA NEW SHARDA MANDIR ROAD, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380007 THEA0000000000A00086 1 DR JIVANLAL HUKAMCHANDJI PAREKH C/O.DHANRAJ & CO., RESHAM BAZAR ITWARI, , NAGPUR INDIA Maharashtra 444444 THEA0000000000J00051 13 DR SUMATILAL VIRCHAND MODI NO.1 NEW ANJALI SOCIETY, VASANA, , AHMEDABAD INDIA Gujarat 380007 -

ALTRIM-Catalogue-2018-21.Pdf

India & Southeast Asia Architectural Travel Guides CATALOGUE 2018-2021 Connecting local culture and architecture in a unique and surprising manner Indian Architectural Travel Guides NEW JAIPUR 230 pages Jaipur is a melting pot of Rajput, Mughal and several other cultures and is With 228 colour photographs, also the seat of a generous amount of vernacular tradition. The visitor will 22 maps and 102 plans also find a contemporary architecture infusing new forms with the legacy of 5 x 7.25” (126 x 184 mm) the past and the spirit of place. ISBN: 978-84-942342-4-8 Price: 25€ / 30$ / 22£ 7 itineraries, 166 buildings and places to visit, Buildings index list Jaipur’s bibliography Facts for the visitors chapter JAIPUR Talkatora TalkatoraSamode Haveli Anokhi Museum Samode Haveli Badrinath Temple Bihari ji ka Temple Panna Meena ka Kund Sagar Lake GOVIND DEV Srijagat Shiromaniji Temple Gaitore ki Chhatriyan Kale Hanumanji ka Mandir COLONY GOVIND DEV Kale Hanumanji ka Mandir COLONY Amber Palace Govind Devji Temple Maotha Lake Govind Devji Temple RAMCHANDRA CHAND MAHAL CHAUKARI COLONY Diwan-I-Khas Hawa Mahal Road RAMCHANDRA CHAUKARI Sawai Man Singh CHAND MAHAL Town Hall COLONY City Palace Diwan-I-Khas Hawa Mahal Road Sawai Man Singh Jantar Mantar Town Hall Tripolia Gate City Palace Sargasuli (Isarlat) Raghunathji Temple Hawa Mahal BADI CHAUPAR Jantar Mantar Way to Jaigarh, Govt. Public Library Nahargarh Fort Tripolia Gate Sargasuli (Isarlat) Raghunathji Temple Hawa Mahal BADI CHAUPAR Govt. Public Library Jal Mahal Jaipur JOHRI BAZAR Rajasthan School -

Ahmedabad City Map Pdf Free Download

Ahmedabad city map pdf free download Continue The actual size of the Ahmedabad map is 613 X 814 pixels, the file size (in bytes) is 121722. You can open this downloadable and printed map of Ahmedabad by clicking on the map of yourself or this link: Open the map. The actual size of the Ahmedabad map is 557 X 775 pixels, the file size (in bytes) is 163573. You can open, download and print this detailed map of Ahmedabad by clicking on the map yourself or by clicking on this link: Open the map. The actual size of the Ahmedabad map is 1843 X 1405 pixels, the file size (in bytes) is 317955. You can open this downloadable and printed map of Ahmedabad by clicking on the map of yourself or this link: Open the map. The actual size of the Ahmedabad map is 3213 X 2436 pixels, the file size (in bytes) is 577895. You can open, download and print this detailed map of Ahmedabad by clicking on the map yourself or by clicking on this link: Open the map. Car rental on OrangeSmile.com OrangeSmile.com is an expert on online travel booking, providing reliable services for car rental and hotel booking. We have more than 25,000 destinations with 12,000 rental offices and 200,000 hotels around the world. Secure Server Head Office Weegschaalstraat 3, Eindhoven 5632 CW, Netherlands No31 40 40 150 44 Privacy Policy Terms About Us Copyright © 2002 - OrangeSmile Tours B.V. OrangeSmile.com (OrangeSmile.com) Under the direction and direction of IVRA Holding B.V. -

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India Has Witnessed Strong Growth in Past Few Years

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India has witnessed strong growth in past few years. India is emerging as a preferred destination for international patients due to availability of best in class treatment at fraction of a cost compared to treatment cost in US or Europe. Hospitals here have focused its efforts towards being a world-class that exceeds the expectations of its international patients on all counts, be it quality of healthcare or other support services such as travel and stay. Why Gujarat ? With world class health facilities, zero waiting time and most importantly one tenth of medical costs spent in the US or UK, Gujarat is becoming the preferred medical tourist destination and also matching the services available in Delhi, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. Gujarat spearheads the Indian march for the “Global Economic Super Power” status with access to all Major Countries like USA, UK, African countries, Australia, China, Japan, Korea and Gulf Countries etc. Gujarat is in the forefront of Health care in the country. Prosperity with Safety and security are distinct features of This state in India. According to a rough estimate, about 1,200 to 1,500 NRI's, NRG's and a small percentage of foreigners come every year for different medical treatments For The state has various advantages and the large NRG population living in the UK and USA is one of the major ones. Out of the 20 million-plus Indians spread across the globe, Gujarati's boasts 6 million, which is around 30 per cent of the total NRI population.