Research on Display a Guide to Collaborative Exhibitions for Academics Edited by Laura Humphreys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Geffrye Museum Trust

THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 Company Number 2476642 Charity Number 803052 THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 Presented to Parliament Pursuant to Article 6 (2)(b) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 (Audit of Non-profit-making Companies) Order 2009 (SI 2009-476) Ordered By the House of Commons to be printed on 9th July 2012 HC 304 London: The Stationery Office £10.75 © The Geffrye Museum Trust Ltd (2012) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context The material must be acknowledged as The Geffrye Museum Trust Ltd copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is also for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk This document is also available from our website at www.geffrye-museum.org.uk ISBN: 9780102977349 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2487680 07/12 21997 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST (Company Number 2476642) ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR -

The Geffrye Museum Trust Annual Report and Financial Statements Year Ended 31 March 2012. HC 304 Session 2012-2013

THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 Company Number 2476642 Charity Number 803052 THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2012 Presented to Parliament Pursuant to Article 6 (2)(b) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 (Audit of Non-profit-making Companies) Order 2009 (SI 2009-476) Ordered By the House of Commons to be printed on 9th July 2012 HC 304 London: The Stationery Office £10.75 © The Geffrye Museum Trust Ltd (2012) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context The material must be acknowledged as The Geffrye Museum Trust Ltd copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is also for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk This document is also available from our website at www.geffrye-museum.org.uk ISBN: 9780102977349 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2487680 07/12 21997 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST (Company Number 2476642) ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR -

The Art Fund in 2014/15

The Art Fund in 2014 /15 The Art Fund in 2014/15 Report of the Board of Trustees Chairman’s welcome p3 Mission and objectives p4 Art Acquisitions p10 Joint acquisitions and tours p18 Curators p23 Gifts, bequests and legacies p24 Public fundraising appeals p26 Sector Art Happens p33 Art Fund Prize for Museum of the Year p34 Digital initiatives and new audiences p37 Community National Art Pass p41 Art Quarterly p43 Supporters p44 Resources Operations p51 Finance review p52 2 The Art Fund in 2014/15 3 Chairman’s welcome Ever since its foundation in 1903, the Art Fund has played a vital role in enhancing the health and quality of the UK’s museums and galleries, meeting the challenges of the hour whenever and wherever they have arisen. Budget cuts, the changing expectations of Since 2010, the Art Fund has supported We are doing all we can to help museums audiences, and the relentless development the curatorial profession by funding various attract, entertain and inform those who visit of new technologies are amongst the training and research opportunities. them. We believe in the power of art in problems – and opportunities – faced by In 2014 we gave £402,000, more than ever contemporary society and we are proud of the museum and arts sector today. We before, to this end – vitally important, in all we have done in its service in 2014, with have tried to help on all fronts: in 2014, our view, for the health and vitality of our the help of all of our supporters. alongside the grants for acquisitions that public art collections. -

Executive Summary

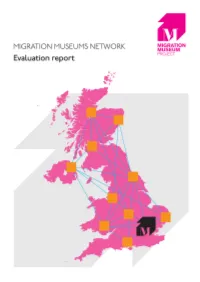

Executive summary This evaluation report reflects on a pilot year for a proposed Migration Museums Network that ran from November 2016 to November 2017. The Migration Museum Project (MMP) coordinated this pilot to gauge the demand and need for a Network to increase and improve work on migration and related themes across the museums, heritage and arts sectors (hereafter ‘heritage sector’) in the UK. The aims of the Network were to raise awareness of the growth of work on the important theme of migration, to share best practice and create opportunities for increased learning and collaboration. The pilot was supported by Arts Council England and the Paul Hamlyn Foundation, and aligns with MMP’s aim of creating a permanent home for the Migration Museum in London, whilst learning from and supporting work on migration themes across the UK. The pilot was guided at all stages by a steering group that met regularly. At the outset it was agreed that the main goals of the pilot would be to: § Update existing scoping research conducted in 2009 by IPPR that mapped representation of migration themes across the heritage sector § Conduct a wide-reaching online survey to contribute to this research and gauge interest in the Network; and § Coordinate two events, in London and Newcastle, to bring people together to learn and network This report will describe the main activities of the pilot, analyse feedback, critically assess MMP’s learning, and conclude with proposed next steps. 2 + Contents 1 Network highlights 2 Network aims 3 Initial research and steering -

COMCOL NEWSLETTER N O

No 35 July COMCOL NEWSLETTER 2020 International Committee for Collecting Contemporary Collecting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Visiting the hairdressing salon in Espoo, Finland. Photo Espoo City Museum, Leena Sipponen Contents Letter from the Chair Danielle Kuijten 1 Conference Review, “What’s Missing? Letter from the Collecting and Exhibiting Europe” Laurie Cosmo 3 Chair Contemporary Collecting and COVID-19 Alexandra Bounia 8 Different ways to document COVID-19 pandemic: Danielle Kuijten Short Example from Espoo City Museum, Finland Riitta Kela 14 Call for Papers: an ethnology lab on the working of COVID-19 on Museums Dear members, 17 Summary of the debate on the new museum definition First of all, I want to speak some words to you, in this surreal Alina Gromova 18 time many are faced with a diversity of challenges, both COMCOL Members Survey 2020: professional and personal. We cannot see these separately as Definition they shape who we are and how we cope. !erefore I hope Alexandra Bounia and Danielle Kuijten 21 you, your families and friends are all safe and healthy, and COMCOL Members Survey 2020: that you "nd support both with those close to you but also A brief report on expectations and relations Alexandra Bounia and Danielle Kuijten 24 with your colleagues worldwide. 1 Editorial 28 COMCOLnewsletter / No 35 / July 2020 2 During the past months as we all had to deal with regulations to help "ght the virus, one of the commonalities was that most of us were con"ned in our homes and our institutes were faced with a long absence of visitors. -

The Geffrye Museum Trust Annual Report and Financial Statements Year Ended 31 March 2011

THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2011 Company Number 2476642 Charity Number 803052 THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2011 Presented to Parliament Pursuant to Article 6 (2)(b) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 (Audit of Non-profit-making Companies) Order 2009 (SI 2009-476) Ordered By the House of Commons to be printed on 11 July 2011 HC 1120 London: The Stationery Office £10.25 © The Geffrye Museum Trust (2011) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context The material must be acknowledged as Geffrye Museum copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is available for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk. This document is also available from our website at www.geffrye-museum.org.uk. ISBN: 9780102972726 Printed in the UK by The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID: 2435493 07/11 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST (Company Number 2476642) ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2011 -

The UK's Ageing Population

The UK’s Ageing Population: Challenges and opportunities for museums and galleries Dr Kate A. Hamblin and Professor Sarah Harper Oxford Institute of Population Ageing, University of Oxford Page Title | 1 The UK’s Ageing Population: Challenges and opportunities for museums and galleries Dr Kate A. Hamblin and Professor Sarah Harper Oxford Institute of Population Ageing, University of Oxford The British Museum was founded in 1753, the first national public museum in the world. From the beginning it granted free admission to all ‘studious and curious persons’. Visitor numbers have grown from around 5,000 a year in the eighteenth century to nearly 6 million today. The collection of the British Museum comprises over 8 million objects spanning the history of the world’s cultures: from the stone tools of early man to twentieth century prints. Partnerships and learning are central to the Museum’s work, making the collections accessible to as wide an audience as possible, locally, nationally and internationally. More information about the British Museum can be found at www.britishmuseum.org The Oxford Institute of Population Ageing, University of Oxford was established in 1998, funded by a grant from the National Institute of Health (National Institute on Aging - NIA) to establish the UK’s first population centre on the demography and economics of ageing populations. The Institute’s aim is to undertake multi-disciplinary research into the implications of population change. More information about the Institute can be found here: www.ageing.ox.ac.uk -

Annual Report and Accounts Year Ended 31 March 2020

The Geffrye Museum Trust Annual Report and Accounts Year Ended 31 March 2020 Company Number 2476642 Charity Number 803052 HC 736 The Geffrye Museum Trust Annual Report and Accounts Year Ended 31 March 2020 Company Number 2476642 Charity Number 803052 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Article 6 (2)(b) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 (Audit of Non-profit making Companies) Order 2009 (SI 2009 No.476) Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 17th December 2020 HC 736 OGL © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. ISBN 978-1-5286-2120-5 CCS0720865132 12/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office CONTENTS TRUSTEES AND PROFESSIONAL ADVISORS 1-2 STRATEGIC REPORT 2019-20 3-28 DIRECTORS' REPORT 29-30 REMUNERATION REPORT 31-32 GOVERNANCE STATEMENT 33-43 STATEMENT OF TRUSTEES' AND ACCOUNTING OFFICER'S RESPONSIBILITIES 44-45 THE CERTIFICATE AND REPORT OF THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL TO THE MEMBERS OF THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST 46-49 STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL ACTIVITIES 50-51 BALANCE SHEET 52 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS 53 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 54-74 MUSEUM OF THE HOME (THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST) ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Directors and Trustees: The directors of the charitable company (the charity) are its trustees for the purpose of charity law and throughout this report are collectively referred to as the trustees. -

Museum-University Partnerships in REF Impact Case Studies: a Review

Museum-university partnerships in REF impact case studies: a review May 2016 Prepared by the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement A report for the Museum University Partnerships Initiative The Museum University Partnership Initiative (MUPI) is a collaboration between Share Academy and the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE), funded by Arts Council England. The project aims to maximise the potential for museums and universities to work together to mutually beneficial aims. It explores how the Higher Education sector can be opened up to smaller and medium sized museums whose unique collections and engagement expertise are often an underutilised resource that could benefit academics, teaching staff, and students within the Higher Education sector, whilst adding value to the work of the museums involved and contributing to their long term resilience. This report shares the results of a specific component of MUPI, a review of how museum-university partnerships featured in the REF. The MUPI project involved a range of activities alongside this review. These included: • Networking events (‘sandpits’) to bring together university and museum staff to develop project ideas • A pilot study of museum-university partnerships involving a literature review, survey and qualitative interviews • A review of other strategic partnership initiatives • A stakeholder event where the interim findings of the project were shared (March 2016) • Convening an advisory group and funders forum Full details of the MUPI project can be found on the NCCPE website where other outputs from the project can also be accessed: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/work-with-us/current- projects/museum-university-partnerships-initiative Introduction The assessment of impact in the Research Excellence Framework (REF) The 2014 Research Excellence Framework introduced the assessment of research impact for the first time. -

The Geffrye Museum Trust

The Geffrye Museum Trust Annual Report and Accounts Year Ended 31 March 2019 Company Number 2476642 Charity Number 803052 HC 241 The Geffrye Museum Trust Annual Report and Accounts Year Ended 31 March 2019 Company Number 2476642 Charity Number 803052 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Article 6 (2)(b) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 (Audit of Non-profit making Companies) Order 2009 (SI 2009 No.476) Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 5th November 2019 HC 241 © Crown copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at: https://www.gov.uk/official-documents Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at info@Geffrye- museum.org.uk ISBN 978-1-5286-1182-4 CCS0419010394 11/19 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office CONTENTS TRUSTEES AND PROFESSIONAL ADVISORS 1 STRATEGIC REPORT 2018-19 2-19 DIRECTORS' REPORT 20-21 REMUNERATION REPORT 22-23 GOVERNANCE STATEMENT 24-31 STATEMENT OF TRUSTEES' AND ACCOUNTING OFFICER'S RESPONSIBILITIES 32 THE CERTIFICATE AND REPORT OF THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL TO THE MEMBERS OF THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST 33-35 STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL ACTIVITIES 36-37 BALANCE SHEET 38 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS 39 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 40-61 THE GEFFRYE MUSEUM TRUST ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2019 Directors and Trustees: The directors of the charitable company (the charity) are its trustees for the purpose of charity law and throughout this report are collectively referred to as the trustees. -

Solent Museums Conference Feb 2016 Copy.Pptx

05/02/16 Hampshire Solent Open Forum 2016 Bernard Donoghue Director, ALVA Monday 1st February 2016 • The national representative body for the UK’s most popular, iconic and important museums, galleries, heritage sites, historic houses, gardens, churches, cathedrals, palaces, castles, zoos and leisure attractions. 1 05/02/16 2 05/02/16 • Director, Association of Leading Visitor Attractions • Chairman, London International Festival of Theatre • Chairman, Council of WWF-UK • Chairman, Tourism Alliance • Deputy Chairman, Kids in Museums • Trustee: – Geffrye Museum of the Home; Heritage Alliance; National Funding Scheme; St Paul’s Cathedral; The Prince’s Regeneration Trust Last year: • Three Council meetings Shakespeare Birthplace Trust and the RSC Warner Bros. Studio Tour ‘The Making of Harry Potter’ • More people visited the V&A, the Natural History Museum and the Canterbury Cathedral, Canterbury, Kent. Westminster Abbey Science Museum, combined, than visited Venice • Two marketing seminars: domestic (Summer) and inbound (Winter); crisis management workshops; lobbying issues. • More people visited the British Museum and the National Gallery, • One benchmarking seminar (November); qualitative visitor experience, financial combined, than visited Barcelona benchmarking (ticketing, retail, catering) and mystery guest • Six-monthly meetings of directors of: • More people visited the Southbank Centre, Tate Modern and Tate – HR Finance Britain, combined, than visited Hong Kong – Fundraising and Development Education – Membership and Friends’ Schemes -

The Furniture History Society May 2020

The Furniture History Society Newsletter 218 May 2020 In this issue: Recreating the Context of the Met Side Table | Society News | Tribute | Society Events | Other Notices | Book Reviews | ECD News and Report | Reports on Society Events | Grants | Publications Recreating the Context of the Met Side Table n 1926, the Metropolitan Museum of provided an opportunity to undertake I Art acquired an early Georgian side a comparative study of all three tables table (Fig. 1), which combines a strong and compile important new information. architectural character with an orderly Combined with archival material, this expression of neo-Palladian vocabulary study has allowed for new observations and retains its original faux-painted and speculations with regard to the tables’ mahogany and parcel-gilt decorative provenance, manufacture and original scheme.1 decorative finishes. Executed in a similar style that evokes The Met side table, as well as the pair the work of William Kent (c. 1685–1748), of side tables at Temple Newsam,3 are a pair of almost identical white and gold attributed to Matthias Lock (c. 1710–70), side tables, originally from Ditchley after a design by Henry Flitcroft (1697– Park, Oxfordshire (Fig. 2) can be found 1769).4 Their design corresponds very at Temple Newsam House (LEEAG. closely to a pencil drawing by Lock for a FU.1954.0009), which is part of the Leeds side table in a drawing, now at the Victoria Museum collection in Yorkshire.2 and Albert Museum, London (Fig. 3).5 The three side tables may in fact be Several variants of this side table’s more closely related than previously design exist — all attributed to Lock on thought: recent visits to Temple Newsam the basis of the drawing — and many Fig.