John Baldessari Creates a New Kind of Chaos: Read a 1986 Profile from the Artnews Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornell University College of Architecture

Cornell University ANNOUNCEMENTS College of Architecture Architecture Art City and Regional Planning 1966-67 Academic Calendar 1965-66 1966-67 Freshman Orientation s, Sept. 18 s, Sept. 17 Registration, new students M, Sept. 20 M, Sept. 19 Registration, old students T, Sept. 21 T, Sept. 20 Instruction begins, 1 p.m. w, Sept. 22 w. Sept. 21 Midterm grades due w, Nov. 10 w, Nov. 9 Thanksgiving recess; Instruction suspended, 12:50 p.m. W, Nov. 24 W, Nov. 23 Instruction resumed, 8 a.m. M, Nov. 29 M, Nov. 28 Christmas recess: Instruction suspended, 12:50 p.m. s, Dec. 18 W, Dec. 21 (10 p.m. in 1966) Instruction resumed, 8 a.m. M, Jan. 3 Th, Jan. 5 First-term instruction ends s, Jan. 22 s, Jan. 21 Registration, old students M, Jan. 24 M, Jan. 23 Examinations begin T, Jan. 25 T , Jan. 24 Examinations end w, Feb. 2 w, Feb. 1 Midyear recess Th, Feb. 3 Th, Feb. 2 Midyear recess F, Feb. 4 F, Feb. 3 Registration, new students s, Feb. 5 s, Feb. 4 Second-term instruction begins, 8 a.m. M, Feb. 7 M, Feb. 6 Midterm grades due s, Mar. 26 s, Mar. 25 Spring recess: Instruction suspended, 12:50 p.m. s, Mar. 26 s, Mar. 25 Instruction resumed, 8 a.m. M, Apr. 4 M, Apr. 3 Second-term instruction ends, 12:50 p.m. s, May 28 s, May 27 Final examinations begin M, May 30 M, May 29 Final examinations end T , June 7 T , June 6 Commencement Day M, June 13 M, June 12 The dates shown in the Academic Calendar are tentative. -

Oral History Interview with Richard Bellamy, 1963

Oral history interview with Richard Bellamy, 1963 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview B: BAKER RB: RICHARD BELLAMY B: I'm about to interview several individuals concerning the Hansa Gallery, which formerly existed in New York City and has for some years been closed. The first individual I'm going to speak to about it is Richard Bellamy, now the director of the Green Gallery. Mr. Bellamy was not associated with the very first days of the Hansa, however, so I'm going to read first, two statements about the origins of the Hansa as a general introduction. One of them is adapted from the Art Student League's News of December 1961. In December 1951 quote, ASix unknown artists all quite young held a joint exhibition of their works in a loft studio at 813 Broadway. The artists were Lester Johnson, Wolf Kahn, John Grillo, Felix Pasilis, Jan Muller and Miles Forst. A813 Broadway@, as this joint cooperation venture was called on a woodcut announcement made by Wolf Kahn, was visited by about 300 artists and two art critics, Thomas B. Hess of Art News and Paul Brach of the Arts Digest. The show led to the founding of the best of the downtown cooperative galleries, the Hansa Gallery. 813 Broadway announced a new interest in figurative painting by a group which had drunk deep at the Pirean springs of abstract expressionism.@ In Dody Muller's account of her husband, Jan's life prefacing the catalogue on Jan Muller, prepared by the Guggenheim Museum for the January, February 1962 exhibition of his works, the statement is made, quote, AIn a sense the 813 Broadway exhibition contained the rudiments of the Hansa Gallery, which was to form on East Twelfth Street and which opened in the autumn of 1952. -

PAVIA, PHILIP, 1915-2005. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar Archive of Abstract Expressionist Art, 1913-2005

PAVIA, PHILIP, 1915-2005. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, 1913-2005 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Pavia, Philip, 1915-2005. Title: Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, 1913-2005 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 981 Extent: 38 linear feet (68 boxes), 5 oversized papers boxes and 5 oversized papers folders (OP), 1 extra oversized papers folder (XOP) and AV Masters: 1 linear foot (1 box) Abstract: Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art including writings, photographs, legal records, correspondence, and records of It Is, the 8th Street Club, and the 23rd Street Workshop Club. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Source Purchase, 2004. Additions purchased from Natalie Edgar, 2018. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Elizabeth Russey and Elizabeth Stice, October 2009. Additions added to the collection in 2018 retain the original order in which they were received. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, Manuscript Collection No. -

Jackie Lipton

JACKIE LIPTON Solo Exhibitions AMP Gallery Provincetown MA 2017 Schoolhouse Gallery Provincetown MA July 2014 Corinne Robbins Gallery Paintings Brooklyn April-June 2009 Boreas Gallery Brooklyn New York 2004 Art Resources Transfer Gallery NYC Paintings 2002 Art Resources Transfer Gallery NYC Blindsight 2001 RamScale Art Associates/Danette Koke Fine Art NYC 1995 RamScale Art Associates/Danette Koke Fine Art NYC 1992 Condeso/Lawler Gallery, NYC January 1987 WARM Gallery Minneapolis February 1985 Condeso/Lawler Gallery NYC January 1985 Condeso/Lawler Gallery NYC January 1984 Whitney Museum of American Art, The Art Resources Center Gallery curated by Richard Armstrong at ARC 185 Cherry Street, a project of the Whitney Museum JL Paintings and Drawings NYC 1974 Selected Group Exhibitions AMP Gallery Provincetown MA 2017 Life Size ll, Anthony Philip Fine Art, Brooklyn 2017 Through the Rabbit Hole 2, Sideshow Gallery, Brooklyn 2017 Schoolhouse Gallery, Gallery Artists, Provincetown MA 2013-2017 Postcards From the Edge, Metro Pictures, NYC 2017 West Chelsea Open Studios, New York City 2017 Through the Rabbit Hole, Sideshow Gallery, Brooklyn NY 2016 High Line Open Studios. New York City 2016 Sikkema Jenkins Postcards From the Edge NY 2016 Visible, Invisible Westbeth Gallery NYC November 2015 Figuring Abstraction Westbeth Gallery NYC October 2015 Postcards From the Edge Luhring-Augustine NYC 2015 Life on Mars Gallery, Summer Invitational, 2014 Luhring Augustine Visual Aids NYC January 2014 Westbeth Printmakers NYC October 2013 No Regrets 6 Women -

Chouinard: a Living Legacy

CHOUINARD: A LIVING LEGACY THE LAST YEARS (1960-1972) – Nobuyuki Hadeishi he only record of the last day at Chouinard – the commencement ceremony of 1972 – was made by photography instructor TGary Krueger. One of his photos shows the faculty, friends, relative, and graduates seated in the patio. This picture tells the story of Chouinard. Though many teachers are missing, old-timers were there, including Watson Cross and Don Graham (in the lower left looking pensive). Graham was chairman of the faculty, essentially our boss. Next to him is Lou Danziger, advertising design teacher. In 1970 he refused an offer from the CalArts administrators to teach at the transitional facility – Villa Cabrini, a former Catholic girl’s school – because he felt needed at Chouinard. The head of the basic design program, Bill Moore, is in the next row in the characteristic pose he took when not happy with student work. Missing is his trademark cigarette. For 34 years, Bill Moore taught the basics of design as if they were a true science. He was the most feared in- structor, both hated and loved. Whenever Chouinardians get together, his name comes up. At the center of some of the great Chouinard controversies in the 1960s; he once torched a work by Ed Ruscha in the school gallery with his famous Zippo lighter. As he burnt a corner of Ruscha’s piece, which incorporated cigarette butts as design ele- ments, he said with authority, “What this piece needs is a little burnt edge to complete it.” By 1955, Nelbert Chouinard had retreated from admin- istrative involvement in her school and Mitch Wilder was hired as director. -

The Early Work of Miriam Schapiro: the Beginnings of Reconciliation Bet\Veen the Artist and the Woman1

The Early Work of Miriam Schapiro: The Beginnings of Reconciliation bet\veen the Artist and the Woman1 Katherine M. Duncan Miriam Schapiro has been a prime motivating force in Columbia. Missouri. 10 New York City in 1952. Schapiro the feminist art movement which developed during the helped to suppon them by working tlm.-e jobs as teacher, seventies. Her collages from these )'ears are filled with bookstore clerk, and secretary. They developed a circle of domestic imagery through which she states her concern for friends in the city, among them neighbors Joan Mitchell and women. She has also lent validity to the decorative art Phill ip Gus1on. They shared camaraderie with the loose movement through the revival of patterning and decoration. group of abstract expressionists which met regularly to As Thalia Gouma-Peterson demonstrated in a 1980 discuss painti ng at the Club or Cedar Street Thvem.• exhibition catalogue. Schapiro did not arrive at her purpose Schapiro said she ..began making abstract expres in the art world without great personal struggle.' During the sionist paintings .. during that time and became "visible·· as fifties she worked in the mainstream mode of abstract an artist.• It is apparent from her thoughts about this period expressionism. Her role as a woman and artist in the an 1ha1 she had not yet developed an independent and authentic ,ociely of New York. a society which seemed almost totally personal style. but was instead foIJowing suit. She noted dominated by men, was in the beginning unclear. During 1ha1 she .. loved New York. was comfortable painting in the this era. -

Press No More Boring Art the New Yorker

No More Boring Art John Baldessari’s crusade. by Calvin Tomkins (October 18, 2010) Baldessari’s “Self-Portrait (with Brain Cloud)” (2010). Marian Goodman Gallery, NY / Paris; Photograph: Franziska Wagner Now that contemporary art has become a global enterprise, we tend to forget that a few pockets of regional difference still exist. In Los Angeles, for example, artists rarely talk about Andy Warhol. Warhol’s shadow hangs heavy over the international art world, but not in L.A., where the most relevant artist of the moment, the seventy-nine-year-old John Baldessari, said recently that he “hadn’t thought about Warhol in forty years.” Baldessari’s endlessly surprising retrospective, which was on view all summer at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, comes to New York this month, opening on October 20th at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The fact that none of our modern or contemporary museums could find room for it in their schedules suggests a strain of parochialism at work here, too, but who knows? Baldessari’s contrarian brand of conceptual, photography-based art-about-art has so few regional or even national characteristics that it probably belongs at the Met, among all those certified treasures of fifty centuries. Baldessari has made a career out of upsetting priorities and defying expectations. “Pure Beauty,” an early work that doubles as the exhibition’s title, consists of those two words, painted by a professional sign painter in black capital letters on an off-white canvas. When Baldessari had it done, in the mid- nineteen-sixties, he was teaching art at a junior college near his home in National City, California, a working-class town near the Mexican border, and painting in his spare time. -

Solo Exhibitions Corinne Robbins Gallery, Paintings, Brooklyn, New

Solo Exhibitions Corinne Robbins Gallery, Paintings, Brooklyn, New York, April-June, 2009 Boreas Gallery, 2-Person Show, Brooklyn, New York, 2004 Art Resources Transfer, NYC, Paintings and Drawings, 2002 Art Resources Transfer, NYC, Blindsight, 2001 RamScale Art Associates/Danette Koke Fine Art, NYC, 1995 RamScale Art Associates/Danette Koke Fine Art, NYC, 1992 Condeso/Lawler Gallery, NYC, January 1987 WARM Gallery, Minneapolis, February 1985 Condeso/Lawler Gallery, NYC, January 1985 Condeso/Lawler Gallery, NYC, January 1984 Art Resources Center Gallery, My Paintings and Drawings at Cherry Street Gallery, a project space of the Whitney Museum of American Art NYC, 1974 Selected Group Exhibitions Sound and Light, Schoolhouse Gallery, Provincetown, MA, 2012 Cheim and Read, Visual Aids Benefit, NYC, 2012 Westbeth Printmakers, NYC, October, 2011 High Line Open Studios, New York City, October, 2011 NYFA Show on Gouvenir's Island, NY, 2011 Fine Arts Work Center Gallery, Prints, Provincetown, MA, 2011 CRG Gallery, Postcards From the Edge, Visual Aids, NYC, 2011 High Line Open Studios, New York City, October, 2010 High Line Open Studios, New York City, March, 2010 artStrand Gallery, Invitational Painting Show, Provincetown, Mass. 2010 Provincetown Art Association, Generations, 2009 Zieher Smith Gallery, Postcards From the Edge, Visual Aids, NYC, 2010 artStrand Gallery, paperJam Drawing Show, Provincetown, Mass. 2009 A Gathering of the Tribes,"Back Wall Exhibition" 2009 Highline Open Studios, New York City, 2009 Metro Pictures, Postcards From the -

Eric Firestone Gallery Is Pleased to Announce Its Participation in The

Eric Firestone Gallery is pleased to announce its participation in The Armory Show, New York (March 7-10, 2019; Pier 90, Focus Section, booth F-3) with a solo presentation of work by Miriam Schapiro from 1960 to 1976. Schapiro (1923-2015) struggled for acceptance within the male-dominated world of Abstract Expressionism, nevertheless becoming the first woman artist to have a solo show at André Emmerich Gallery in 1958. Her work of the late 1950s is gestural and painterly, while remaining rooted in the body and experiences of womanhood. By 1960 Schapiro began to include more geometric elements in her paintings, especially the motif of windows and boxes. These “Shrine” paintings, a group of which will be on view, incorporate the form of an egg within rectangular apertures: homages to art history and the female experience. In 1967, following her move to Southern California, where she and her husband Paul Brach would teach at The University of California, San Diego, she developed a unique vocabulary of forms and processes. She was one of the first artists to explore computer imaging, using it to develop hard-edged, illusionistic geometric abstractions, still rooted in the female body (termed “central-core” imagery). Schapiro’s experimentation did not end there; by 1972, along with Judy Chicago she had founded, the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts, and created the legendary installation "Womanhouse." She challenged the dichotomy of "high" art by incorporating decorative art and crafts that were traditionally gendered as female. These became part of works she termed "femmage" to denote the continuity of high art collage and work made by anonymous women - which she collected and was given by other artist friends. -

DOUGLAS GARY LICHTMAN UCLA School of Law • 405 Hilgard Avenue • Los Angeles CA 90095 • (310) 267-4617 • [email protected]

DOUGLAS GARY LICHTMAN UCLA School of Law • 405 Hilgard Avenue • Los Angeles CA 90095 • (310) 267-4617 • [email protected] Experience Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law July 2007 through present with a joint appointment in the School of Engineering and Applied Science Professor of Law, The University of Chicago July 2002 through June 2007 (full professor) June 1998 through June 2002 (assistant professor) Editor, The Journal of Law & Economics October 2003 through July 2007 Education Yale Law School, J.D. 1997 • Yale Law Journal • Admitted in Illinois (1997) Duke University, B.S.E. Electrical Engineering / Computer Science 1994 • Graduated 1st in Class Scholarship / Publications Cashing Out Children's Television, 27 UCLA ENTERTAINMENT LAW REVIEW 1 (2020) (also excerpted in Regulation Magazine (Vol. 42, Winter 2020)). Naughty Bits: An Empirical Study of What Consumers Would Mute and Excise from Hollywood Fare if Only They Could, 66 JOURNAL OF THE COPYRIGHT SOCIETY OF THE USA 401 (2019) (with Benjamin Nyblade) (peer reviewed) (selected for presentation as part of the Theodore Eisenberg Poster Session at the 13th Annual Conference on Empirical Legal Studies, November 9, 2018). The Perspiration Principle, 18 JOHN MARSHALL REVIEW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW 463 (2019). The Central Assumptions of Patent Law, 65 UCLA LAW REVIEW 1268 (2018). Patient Patents: Can Certain Types of Patent Litigation be Beneficially Delayed, 46 J LEGAL STUDIES 427 (2017). THE TECH PATENT WARS: WHAT EVERY INVESTOR NEEDS TO KNOW, CLSA University Blue Book (2012). A Patently Obvious Problem, The New York Times (April 16, 2011). Google Book Search in the Gridlock Economy, 53 ARIZONA LAW REVIEW 131 (2011) (symposium in honor of Michael Heller). -

A HIDDEN RESERVE: PAINTING from 1958 to 1965 - Artforum International 3/23/20, 11�18 AM a HIDDEN RESERVE: PAINTING from 1958 to 1965

A HIDDEN RESERVE: PAINTING FROM 1958 TO 1965 - Artforum IntErnational 3/23/20, 1118 AM A HIDDEN RESERVE: PAINTING FROM 1958 TO 1965 IN THE LATE 1950s, painting celebrated some of the greatest triumphs in its history, grandly ordained as a universal language of subjective and historical experience in major shows and touring exhibitions. But only a short while later, its very right to exist was fundamentally questioned. Already substantially weakened by the rise of Happenings and Pop art, painting was shoved aside by art critics during the embattled ascendancy of Minimalism in the mid-ʼ60s. Since then, painters and their champions alike have tirelessly pondered the reasons for their chosen mediumʼs downfall, its abandonment by advanced theoretical discourse. It is not coincidental that “Painting: The Task of Mourning” is the title of Yve-Alain Boisʼs seminal 1986 essay (republished in his 1990 book Painting as Model), which remains the last ambitious attempt to outline a history of modern painting and its endgames.1 For Bois, painting will doubtless survive beyond its postulated conclusions. But for the past several decades, we nevertheless seem to have been presented with only two possible outcomes: the unrelenting yet joyful endgame, a celebration of past painterly devices; and its complement, “bad painting,” the cynical appropriation and parody of the mediumʼs former claims (as when Andy Warhol, Albert Oehlen, and Merlin Carpenter employ avant-garde strategies of montage or monochrome as farce or pose). But how was painting forced to -

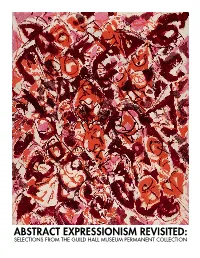

Abstract Expressionism Revisited

ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM REVISITED: SELECTIONS FROM THE GUILD HALL MUSEUM PERMANENT COLLECTION ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM REVISITED: SELECTIONS FROM THE GUILD HALL MUSEUM PERMANENT COLLECTION Joan Marter, PhD 158 Main Street East Hampton, New York 11937 Office: 631-324-0806 Fax: 631-324-2722 guildhall.org Cover image: Lee Krasner Untitled, 1963 Oil on canvas 54 x 46 inches Purchased with aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM REVISITED: SELECTIONS FROM THE GUILD HALL MUSEUM PERMANENT COLLECTION is the catalogue for the exhibition curated for Guild Hall by Joan Marter, PhD. The exhibition is on view from October 26 - December 30, 2019 The exhibition at Guild Hall has been made possible through the generosity of its sponsors LEAD SPONSORS: Betty Parsons Foundation, and Lucio and Joan Noto CO-SPONSORS: Barbara F. Gibbs, and the Robert Lehman Foundation All Museum Programming supported in part by The Melville Straus Family Endowment, The Michael Lynne Museum Endowment, Vital Projects Fund, Hess Philanthropic Fund, Crozier Fine Arts, The Lorenzo and Mary Woodhouse Trust, and public funds provided by New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and Suffolk County. guildhall.org ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to Andrea Grover, Executive Director of Guild Hall and the curatorial staff. It was a great pleasure to work with Christina Strassfield, Casey Dalene, and Jess Frost on this exhibition. Special accolades to Jess Frost, Associate Curator/Registrar of the Permanent Collection, who prepared a digitized inventory of the collection that is now available to all members and interested visitors to Guild Hall.