Reviews / Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

K E N F a R M

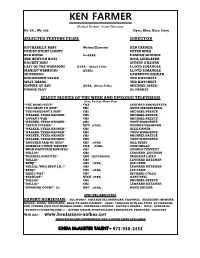

KEN FAR MER (Partial Resume- Actor/Director) Ht: 6ft., Wt: 200 Eyes: Blue, Hair: Grey SELECTED FEATURE FILMS DIRECTOR ROCKABILLY BABY Writer/Director KEN FARMER FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS PETER BERG RED RIDGE Co-STAR DAMIAN SKINNER THE NEWTON BOYS RICK LINKLATER ROCKET MAN STUART GILLARD LAST OF THE WARRIORS (STAR, - Above Title) LLOYD SIMANDLE MANIAC WARRIORS (STAR) LLOYD SIMANDLE SILVERADO LAWRENCE KASDAN UNCOMMON VALOR TED KOTCHEFF SPLIT IMAGE TED KOTCHEFF EMPIRE OF ASH (STAR - Above Title) MICHAEL MAZO POWER PLAY AL FRAKES SELECT MOVIES OF THE WEEK AND EPISODIC TELEVISION (Star, Co-Star, Guest Star) “THE GOOD GUYS” FOX SANFORD BOOKSTAVER "TOO LEGIT TO QUIT" VH1 ARTIE MANDELBERG "THE PRESIDENT'S MAN" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "LOGAN'S WAR" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "AUSTIN STORIES" MTV (STAR) GEORGE VERSHOOR "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS ALEX SINGER "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "ANOTHER PAIR OF ACES" CBS (STAR) BILL BIXBY "AMERICA'S MOST WANTED" FOX (STAR) TOM SHELLY "HIGH MOUNTAIN RANGERS" CBS GEORGE FENNEDY "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "GENERAL HOSPITAL" ABC (RECURRING) MARLENA LAIRD "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "BENJI" CBS (STAR) JOE CAMP "DALLAS, WHO SHOT J.R.?" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "BENJI" CBS (STAR) JOE CAMP "JAKE'S WAY" CBS RICHARD COLLA "BACKLOT" NICK (STAR) GARY PAUL "DALLAS" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "SUPERIOR COURT" (2) NBC (STAR) HANK GRIMER SPECIAL ABILITIES EXPERT HORSEMAN: ALL SPORTS: COLLEGE ALL-AMERICAN, FOOTBALL: EXCELLENT SWIMMER: DIVING: SCUBA: WRESTLING: HAND-TO-HAND COMBAT: USMC: FAMILIAR WITH ALL TYPES OF FIREARMS: CAN FURNISH OWN FILM TRAINED HORSE: BACHELOR'S DEGREE - SPEECH & DRAMA : GOLF: AUTHOR OF "ACTING IS STORYTELLING ©" : ACTING COACH: STORYTELLING CONSULTANT: PRODUCER: DIRECTOR Web Site - www.kenfarmer-author.net THEATRICAL AND COMMERCIAL DVD & AUDIO TAPES AVAILABLE LINDA McALISTER TALENT - 972-938-2433. -

CHICAGO JEWISH HISTORY Spring Reviews & Summer Previews

Look to the rock from which you were hewn Vol. 41, No. 2, Spring 2017 1977 40 2017 chicago jewish historical societ y CHICAGO JEWISH HISTORY Spring Reviews & Summer Previews Sunday, August 6 “Chicago’s Jewish West Side” A New Bus Tour Guided by Jacob Kaplan and Patrick Steffes Co-founders of the popular website www.forgottenchicago.com Details and Reservation Form on Page 15 • CJHS Open Meeting, Sunday, April 30 — Sunday, August 13 Professor Michael Ebner presented an illustrated talk “How Jewish is Baseball?” Report on Page 6 A Lecture by Dr. Zev Eleff • CJHS Open Meeting, Sunday, May 21 — “Gridiron Gadfly? Mary Wisniewski read from her new biography Arnold Horween and of author Nelson Algren. Report on Page 7 • Chicago Metro History Fair Awards Ceremony, Jewish Brawn in Sunday, May 21 — CJHS Board Member Joan Protestant America” Pomaranc presented our Chicago Jewish History Award to Danny Rubin. Report on Page 4 Details on Page 11 2 Chicago Jewish History Spring 2017 Look to the rock from which you were hewn CO-PRESIDENT’S CO LUMN chicago jewish historical societ y The Special Meaning of Jewish Numbers: Part Two 2017 The Power of Seven Officers & Board of In honor of the Society's 40th anniversary, in the last Directors issue of Chicago Jewish History I wrote about the Jewish Dr. Rachelle Gold significance of the number 40. We found that it Jerold Levin expresses trial, renewal, growth, completion, and Co-Presidents wisdom—all relevant to the accomplishments of the Dr. Edward H. Mazur* Society. With meaningful numbers on our minds, Treasurer Janet Iltis Board member Herbert Eiseman, who recently Secretary completed his annual SAR-EL volunteer service in Dr. -

The Construction of Muslim Terrorism in the Kingdom Movie (2007) Directed by Peter Berg: a Reception Theory Magister of Language

THE CONSTRUCTION OF MUSLIM TERRORISM IN THE KINGDOM MOVIE (2007) DIRECTED BY PETER BERG: A RECEPTION THEORY PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Master Degree of Education in Magister of Language Study by: Agung Budi Santoso S200130035 MAGISTER OF LANGUAGE STUDY MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2015 i ii iii 1 THE CONSTRUCTION OF MUSLIM TERRORISM IN THE KINGDOM MOVIE (2007) DIRECTED BY PETER BERG: A RECEPTION THEORY Agung Budi Santoso Magister of Language Study Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta Abstract This study belongs to the literary study. This study analyzes the construction of Muslim terrorism based on reader response reflected in The Kingdom Movie (2007). There are two objectives of the study, the first is to describe the dominant issues by the reviewers in applying reader response theory to Peter Berg‟s The Kingdom movie, and the second is to explain the reason why the dominant issue are perceived differently by reviewers. This study is a qualitative study and using two data sources; they are primary and secondary data. The primary data source is the reviews of The Kingdom movie (2007) by Peter Berg from IMDb (Internet Movie Database). The secondary data of this study are taken from other sources such as literary book, previous studies, articles, journals, and also website related to reader response theory. This study aimed to reveal how the cultural reader response reflected to The Kingdom movie. The dominant issue which is respond by the reviewers is the terrorism dealing with the culture reader response. Keywords: Culture Reader Response, Richard Beach, The Kingdom Abstrak Penelitian ini termasuk dalam penelitian sastra. -

Popular Cultural Islamophobia

CHAPTER 4 POPULAR CULTURAL ISLAMOPHOBIA Muslim representations in Films, News Media, and Television Programs INTRODUCTION Thus far in the book, we have examined Islamophobia from a theoretical perspective, as well as how it manifests in political discourse, and policies and legislation in the context of the War on Terror. Negatively evaluated beliefs and perceptions of Muslims in the post-9/11 context have also been strongly influenced and informed by representations in popular cultural mediums such as film, news media, and television programs. The impact of media in the construction of race has been discussed in great detail by Stuart Hall (1996), as he states, “the media construct for us a definition of what race is, what meaning the imagery of race carries, and what the ‘problem of race’ is understood to be” (p. 161). Indeed, after 9/11 depictions of Muslim terrorists flooded TV and cinema screens reinforcing narratives in the news media about ‘dangerous Muslim men’ and ‘imperilled Muslim women’. This chapter examines Muslim representations in popular cultural mediums after 9/11. The reason I have devoted an entire chapter on analyzing Muslim representations in popular cultural mediums is because a number of people I interviewed for this book directly and unambiguously discussed how they felt the ‘media’ negatively portrayed Muslims and that these depictions have facilitated the growth of stereotypes of Muslims in Canadian society and secondary schools. This chapter examines the types of media that participants discussed in the interview process to demonstrate how these media have circulated the tropes of ‘dangerous Muslim men’, ‘imperilled Muslim women’, and Muslim cultures as being monolithic. -

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706 FILM DOLLFACE Department Head Hair/ Hulu Personal Hair Stylist To Kat Dennings THE HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Camp Sugar Director: Chris Addison SERENITY Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Global Road Entertainment Director: Steven Knight ALPHA Department Head Studio 8 Director: Albert Hughes Cast: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Jóhannes Haukur Jóhannesson, Jens Hultén THE CIRCLE Department Head 1978 Films Director: James Ponsoldt Cast: Emma Watson, Tom Hanks LOVE THE COOPERS Hair Designer To Marisa Tomei CBS Films Director: Jessie Nelson CONCUSSION Department Head LStar Capital Director: Peter Landesman Cast: Gugu Mbatha-Raw, David Morse, Alec Baldwin, Luke Wilson, Paul Reiser, Arliss Howard BLACKHAT Department Head Forward Pass Director: Michael Mann Cast: Viola Davis, Wei Tang, Leehom Wang, John Ortiz, Ritchie Coster FOXCATCHER Department Head Annapurna Pictures Director: Bennett Miller Cast: Steve Carell, Channing Tatum, Mark Ruffalo, Siena Miller, Vanessa Redgrave Winner: Variety Artisan Award for Outstanding Work in Hair and Make-Up THE MILTON AGENCY Kathrine Gordon 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Stylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 and 798 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 6 AMERICAN HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist to Christian Bale, Amy Adams/ Columbia Pictures Corporation Hair/Wig Designer for Jennifer Lawrence/ Hair Designer for Jeremy Renner Director: David O. Russell -

Michael Gold & Dalton Trumbo on Spartacus, Blacklist Hollywood

LH 19_1 FInal.qxp_Left History 19.1.qxd 2015-08-28 4:01 PM Page 57 Michael Gold & Dalton Trumbo on Spartacus, Blacklist Hollywood, Howard Fast, and the Demise of American Communism 1 Henry I. MacAdam, DeVry University Howard Fast is in town, helping them carpenter a six-million dollar production of his Spartacus . It is to be one of those super-duper Cecil deMille epics, all swollen up with cos - tumes and the genuine furniture, with the slave revolution far in the background and a love tri - angle bigger than the Empire State Building huge in the foreground . Michael Gold, 30 May 1959 —— Mike Gold has made savage comments about a book he clearly knows nothing about. Then he has announced, in advance of seeing it, precisely what sort of film will be made from the book. He knows nothing about the book, nothing about the film, nothing about the screenplay or who wrote it, nothing about [how] the book was purchased . Dalton Trumbo, 2 June 1959 Introduction Of the three tumultuous years (1958-1960) needed to transform Howard Fast’s novel Spartacus into the film of the same name, 1959 was the most problematic. From the start of production in late January until the end of all but re-shoots by late December, the project itself, the careers of its creators and financiers, and the studio that sponsored it were in jeopardy a half-dozen times. Blacklist Hollywood was a scary place to make a film based on a self-published novel by a “Commie author” (Fast), and a script by a “Commie screenwriter” (Trumbo). -

Movie's Secret Friiter May Be Recognized 0.5T-71

the House Committee on un-Arnencan Activities investigation of communist influence in Hollywood. Movie's Secret Like many other screenwriters of that era, Maltz had to resort to finding someone to front for him when Blaustein asked him to write the screenplay for "Broken Arrow," based on "Blood Brothers," a friiter May novel by Elliott Arnold. After several people turned Maltz down, he approached his close friend, Michael Blankfort, also a screenwriter and novelist. They had known each Be Recognized other for decades and had dedicated novels to each 0.5T-71 other. s Angeles Times Blankfort agreed to pretend he had written HOLLYWOOD—Six years ago, at a ceremony "Broken Arrow." And unlike the character played by at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sci- Woody Allen in the 1976 movie "The Front," he not ences, blacklisted screenwriters Michael Wilson and only let his name be used for free but also provided Carl Foreman were posthumously awarded Oscars the revisions the studio demanded. Blaustein said for "The Bridge on the River Kwai." that he secretly ran Blankfort's changes by Maltz. It had been an wet secret that Pierre Boulle, If this (arrangement] had gotten out, it would who accepted the original Oscar in 1958, did not have killed the careers of both Blankfort and Blaus- write the screenplay based on his novel. "Everyone tein," Ceplair said. knew Boulle couldn't speak English, let alone write Maltz's widow, Esther, agrees. "It was an act of it," said Larry Ceplair, co-author of "The Inquisition courage and it was an act of friendship," she said. -

Finding Aid for the Steven Jay Rubin Papers Collection Processed

Finding Aid for the Steven Jay Rubin Papers Collection Processed by: Maya Peterpaul, 2.23.18 Revised, Emily Wittenberg, 7.11.18 Finding Aid Written by: Maya Peterpaul, 2.23.18 Revised, Emily Wittenberg, 7.11.18 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION: Origination/Creator: Rubin, Steven Jay Title of Collection: Steven Jay Rubin Papers Date of Collection: ca. 1980s-1990s Physical Description: 3 boxes; 0.834 feet Identification: Special Collection #11 Repository: American Film Institute Louis B. Mayer Library, Los Angeles, CA RIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS: Access Restrictions: Collection is open for research. Copyright: The copyright interests in this collection remain with the creator. For more information, contact the Louis B. Mayer Library. Acquisition Method: Donated by Steven Jay Rubin in 1983. BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORY NOTE: Steven Jay Rubin was born in Chicago, Illinois, on September 9, 1951. Rubin is a film historian and the founder and president of the production company, Fast Carrier Pictures, Inc. He has worked as a publicist for over 150 films and television series. Rubin has also directed and produced various film projects, contributed to DVD commentaries (THE GREAT ESCAPE), and contributed writing to magazines (Cinefantastique, CinemaRetro). Rubin is considered to be an expert on James Bond films, and has written the following books: The James Bond Films (1981), The James Bond Films: A Behind the Scenes History (1981), and The Complete James Bond Movie Encyclopedia (1990). Other books by Rubin include: Combat Films: American Realism, 1945-70 (1981), Combat Films : American Realism, 1945-2010, Reel Exposure : How to Publicize and Promote Today's Motion Pictures (1991), and The Twilight Zone Encyclopedia (2017). -

Jack Oakie & Victoria Horne-Oakie Films

JACK OAKIE & VICTORIA HORNE-OAKIE FILMS AVAILABLE FOR RESEARCH VIEWING To arrange onsite research viewing access, please visit the Archive Research & Study Center (ARSC) in Powell Library (room 46) or e-mail us at [email protected]. Jack Oakie Films Close Harmony (1929). Directors, John Cromwell, A. Edward Sutherland. Writers, Percy Heath, John V. A. Weaver, Elsie Janis, Gene Markey. Cast, Charles "Buddy" Rogers, Nancy Carroll, Harry Green, Jack Oakie. Marjorie, a song-and-dance girl in the stage show of a palatial movie theater, becomes interested in Al West, a warehouse clerk who has put together an unusual jazz band, and uses her influence to get him a place on one of the programs. Study Copy: DVD3375 M The Wild Party (1929). Director, Dorothy Arzner. Writers, Samuel Hopkins Adams, E. Lloyd Sheldon. Cast, Clara Bow, Fredric March, Marceline Day, Jack Oakie. Wild girls at a college pay more attention to parties than their classes. But when one party girl, Stella Ames, goes too far at a local bar and gets in trouble, her professor has to rescue her. Study Copy: VA11193 M Street Girl (1929). Director, Wesley Ruggles. Writer, Jane Murfin. Cast, Betty Compson, John Harron, Ned Sparks, Jack Oakie. A homeless and destitute violinist joins a combo to bring it success, but has problems with her love life. Study Copy: VA8220 M Let’s Go Native (1930). Director, Leo McCarey. Writers, George Marion Jr., Percy Heath. Cast, Jack Oakie, Jeanette MacDonald, Richard “Skeets” Gallagher. In this comical island musical, assorted passengers (most from a performing troupe bound for Buenos Aires) from a sunken cruise ship end up marooned on an island inhabited by a hoofer and his dancing natives. -

Assembly Passes Law to Collect Illegal Weapons

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, JANUARY 15, 2015 RABI ALAWWAL 24, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Expats urged to Kerry, Zarif The Real Fouz: Saudi Arabia join ‘Positive resume How to get floor North Kuwaiti’ nuclear talks the best shape Korea after initiative3 in Geneva7 for37 your brows early20 scare Assembly passes law to Min 04º Max 22º collect illegal weapons High Tide 06:42 & 18:31 Low Tide MP slams Iranian president’s comments on oil 00:46 & 12:08 40 PAGES NO: 16403 150 FILS Omair admits oil By Staff Reporter KUWAIT: The National Assembly yesterday unanimously drop unexpected passed in the first reading a law allowing the interior min- istry to collect unlicensed and illegal firearms and stipulat- KUWAIT: The depth of the oil price drop was unexpect- ing hefty jail sentences against violators. The second read- ed, Kuwait’s oil minister said on yesterday, repeating ing of the law will be debated and voted after two weeks. too that OPEC had made the right decision in not cut- The law stipulates a jail term for seven years and a fine of ting its output. The comments by Ali Al-Omair reflect KD 20,000 for those who trade in unlicensed firearms and how even core Gulf OPEC producers who had led the explosives or in materials for manufacturing them. The decision in November, blocking a call for a cut by oth- penalty applies also to those who smuggle such arms or ers, did not predict the scale of the price collapse of strike deals with terror organizations or cells to sell or buy about 60 percent in the last six months. -

The American Legion Department of Michigan Family Leadership

Official Publication of The American Legion Department of Michigan - www.michiganlegion.org - JULY/AUGUST 2015 Michigan Legionnaire & Wolverine Auxiliaire Vol. LXXXIV No. 1 THE AMERICAN LEGION DEPARTMENT OF MICHIGAN FAMILY LEADERSHIP SAL Commander Fred Ruttkofsky Department Commander Michael Buda Auxiliary President Sue Verville During the 2015 Annual Summer Department Convention the delegates present elected and approved the new leadership for the 2015-2016 Ameri- can Legion membership year. For The American Legion, Michael Buda from Post 364 was elected as your new State Commander, The American Legion Auxiliary elected Sue Verville (Iron River) as the State President, and the Sons of the American Legion elected Fred Ruttkofsky of Squadron 300, as the Detachment Commander for 2015-2016. Wilwin Ride for Our Veterans Saturday July 25, 2015 The ride will be from Mt Pleasant to Sault Ste Marie. Open to all American Legion Riders from any state. Pre registration ap- preciated and we will try to ensure free ride patches for all that pre register. An information packet will be mailed to you. Ride will end at the Kewadin Casino where country music artist Richard Lynch will be hosting a benefit concert for Wilwin lodge Saturday evening. Visit www.michiganlegion.org click on the Wilwin Fundraiser for registration and information. For questions contact Tom Howard at 517-488-4730 or email at [email protected] Registration – Snacks – and registration assignment number, wristband or bike marker. C&S Motorsports – Mt Pleasant MI TIME - 7- 8.30 Ride introduction 8:45 along with Group assignments (will assign to squads based on number of people). -

Hayman Capital

FILED 7/6/2020 2:15 PM JOHN F. WARREN COUNTY CLERK DALLAS COUNTY CAUSE NO. CC-17-06253-C UNITED DEVELOPMENT FUNDING, L.P., § 1N THE COUNTY COURT A DELAWARE LIMITED PARTNERSHIP; § UNITED DEVELOPMENT FUNDING II, § L.P., A DELAWARE LIMITED § PARTNERSHIP; UNITED DEVELOPMENT § FUNDING III, L.P., A DELAWARE § LIMITED PARTNERSHIP; UNITED § DEVELOPMENT FUNDING IV, A § MARYLAND REAL ESTATE § INVESTMENT TRUST; UNITED § DEVELOPMENT FUNDING INCOME § FUND V, A MARYLAND REAL ESTATE § INVESTMENT TRUST; UNITED § MORTGAGE TRUST, A MARYLAND § REAL STATE INVESTMENT TRUST; § UNITED DEVELOPMENT FUNDING § LAND OPPORTUNITY FUND, L.P., A AT LAW NO. 3 DELAWARE LIMITED PARTNERSHIP; E UNITED DEVELOPMENT FUNDING § LAND OPPORTUNITY FUND § INVESTORS, L.L.C., A DELAWARE § LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY § § Plaintiffs, § § § § § J. KYLE BASS; HAYMAN CAPITAL § MANAGEMENT, L.P.; HAYMAN § OFFSHORE MANAGEMENT, INC.; § HAYMAN CAPITAL MASTER FUND, L.P.; § HAYMAN CAPITAL PARTNERS, L.P.; § HAYMAN CAPITAL OFFSHORE § PARTNERS, L.P.; HAYMAN § INVESTMENTS, LLC § § Defendants. § DALLAS COUNTY, TEXAS DECLARATION OF ELLEN A. CIRANGLE IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ REPLY BRIEF RE MOTION TO OBTAIN DOCUMENTS IMPROPERLY DESIGNATED AS PRIVILEGED PURSUANT TO THE CRIME-FRAUD EXCEPTION 07675.00002/1 131047V1 CIRANGLE DECLARATION IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ REPLY BRIEF RE MOTION TO OBTAIN DOCUMENTS PURSUANT TO CRIME-FRAUD EXCEPTION Page 1 My name is Ellen A. Cirangle, my date of birth is July 7, 1963, and my address is 18 Miguel Street San Francisco, California. I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct. 1. I am over eighteen years 0f age. I have never been convicted of a felony 0r a crime 0f moral turpitude.