Downloaded on 2017-02-12T08:05:23Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Aid Volunteering Fair 1

CONTACT Irish Aid Volunteering and Information Centre 27 – 31 Upper O’Connell Street, . Dublin 1 DALYMOUN T Telephone: 01 8546920 Irish Aid T R PA RK e [email protected] DA w www.irishaid.gov.ie/centre C R O K E PA RK NORT H CIRCULA 18 D R ROAD A O R D AR NO Volunteering L RTH ROA C B IR L CUL AC AR CU GH R KH R OAD CI OR OROU T H B E E SE R BS LOCATION RT I T AV S U PH T P NO E TEM P E S E R R TH N PLE R O G NO U D A E ST R D REE I N MOUNTJOY E T N R Fair SQUARE O S RT T R H E TH E F T SOU L R IL E H D ER E M R HIL M I D C SU A K L September 29th 2012 S O S TR R T R E H T EE ET G E E T U R O T REET R S T T S T OT E M BO R S T DE R AC BS M I O REE N D L SEA O PH NELL ST W PAR E R P A G R A N E T R L A S D L H I G N M S RU Q B E A T L U A R CONNOL LY N E TH MA A A O E R C S R R E T R ST N T R S S L E T B E RE N O O T T T E E R T E S T L R O S O ST U B N L G E L O E H I ‘ N I C N R ST A AM F EET P O I TR R PHOENIX R K S N IC E M UNSW NE BR E A T PARK R L ET Y L TRE S T S O R ALB BUSARAS T T C O HE A RE ST D E EET C R E KING ST E R A TH F NOR EET T IE L R L L ST IL P RY D H N R ARBOUR HE OA L D L A H EET K R LD Y ST C E AR I M C A IFS C F L A H T B P T E I E CUST E ET OM L E HOU M R AY SE QU R ST U Y Q AY S N S E CONY T ABBE ED NGHAM ROAD PARK T GATE STREE S T RE BENBURB STR EET H E C F EY T F R U LK I V E R L I RI H R S WA GEOR V E R L I F F E Y C R Y GES WOLFE TONE LO H QUA QUA QUAY HE URG Y ELLIS QU AC B AY B CI TY QUAY VI ARR CTORIA QUAY AN T S QUA US Y A ON STN. -

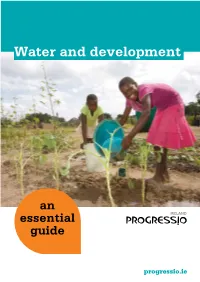

Water and Development

Water and development an essential guide progressio.ie Water for life Water is vital. We use it every day, and we use more of it than we realise. And most of the time, we take water for granted. But not everyone enjoys access to the water they need – with devastating consequences. Around the world many thousands of people die every day due to unsafe water; a huge proportion are children. Tackling this is a huge task. But simply having access to clean drinking water and proper sanitation isn’t the whole story. Many people in poor countries around the world rely on small-scale farming for their livelihoods. With limited or unreliable access to the water they need, they are not able to grow food to feed their families or to sell to make a living. This ‘productive’ use of water underpins development. Without access to water resources, the livelihoods of millions of people are under threat. And it doesn’t stop there. Lack of access to water affects every aspect of people’s lives, from their health to their children’s ability to go to school. In fact, water – having enough of it, and having access to it when you need it – is fundamental to achieving the improvements to health, nutrition, education and the environment laid out in the Millennium Development Goals. So poor and marginalised people must have fair change and sustainable access to water, including the water they need for their livelihoods. starts That’s something Progressio and our partners across the with you world are working towards – and this is also the aim of Progressio’s ‘Waterproof’ campaign. -

1 INDEX to REPORTS Page 1. Representative Church Body

INDEX TO REPORTS Page 1. Representative Church Body......................................................................................3 2. Church of Ireland Pensions Board.......................................................................... 101 3. Standing Committee............................................................................................... 145 4. Church in Society................................................................................................... 221 5. Board of Education ................................................................................................ 237 6. Church of Ireland Youth Department..................................................................... 259 7. The Covenant Council............................................................................................ 271 8. Commission for Christian Unity and Dialogue ...................................................... 275 9. Liturgical Advisory Committee ............................................................................. 293 10. Church of Ireland Council for Mission .................................................................. 305 11. Commission on Ministry........................................................................................ 315 12. Church of Ireland Marriage Council ...................................................................... 339 13. Church’s Ministry of Healing ................................................................................ 343 14. Board for Social Responsibility -

List of GWP Partners

List of GWP Partners Since its inception, GWP has built up a network of Regional Water Partnerships. The Network currently comprises 13 Regional Water Partnerships (RWPs) and 86 Country Water Partnerships (CWPs), and includes more than 3000 Partners located in 1774 countries. Photo: GWP Steering Committee Meeting - December 2016 - Stockholm Updated 21 December 2016 Global Water Partnership (GWP), Global Secretariat, PO Box 24177, 104 51 Stockholm, SWEDEN Visitor’s address: Linnégatan 87D, Phone: +46 (0)8 1213 8600, Fax: + 46 (0)8 1213 8604, e-mail: [email protected] Table of Contents List of GWP Partners.................................................................................................................. 1 GWP Caribbean .......................................................................................................................... 3 GWP Central Africa..................................................................................................................... 6 GWP Central America................................................................................................................. 9 GWP Central and Eastern Europe ............................................................................................ 16 GWP Central Asia and Caucasus .............................................................................................. 21 GWP China................................................................................................................................ 25 GWP Eastern Africa ................................................................................................................. -

Interact Summer 2007

interact The magazine of The option for the poor A new beginning for the Church in Latin America Also in this issue: Water in El Salvador HIV and AIDS in Zimbabwe Qat chewing in Yemen ISSN 1816-045X Summer 2007 interact summer 2007 Contents Nick Sireau/Progresio editorial 3 first person: seeing through a different lens The option for 7 4 news: elections in East Timor the poor 6 update: bulletins from the frontline The insight section of this issue of Interact 7 agenda: committed to peace and justice examines the messages from the 5th General Conference of the Latin American and Caribbean insight: the option for the poor bishops held in Aparecida, Brazil, in May. The articles look in some detail at what it means to be an ‘advocate of justice and defender of the poor’. 8 A new beginning 8 A concern for the poor and powerless is at the Latin American bishops take new heart of Progressio’s approach. We seek to step in church’s journey empower people to tackle the poverty and injustice that they face. This can be seen in the 10 Declaration of intent work described elsewhere in this Interact: in The spirit of Medellín is alive and well Christopher Nyamandi’s work with young people in Zimbabwe (see page 14), or Hans Joel’s work action with communities in El Salvador (page 13), or Francisco Hernandez’s work with the environmental movement of Olancho in Honduras 12 Putting the poor first (page 6). The challenges posed by climate change Progressio’s approach is always grounded in what we ‘see’ of the world: the experience of our viewpoint work in countries in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Asia; the views of our partners 14 and the people we work with in those countries; 13 Clear water and, as our environmental advocacy coordinator A community in El Salvador Sol Oyuela describes (page 12), our analysis of the fights for its rights issues that the people we work with face. -

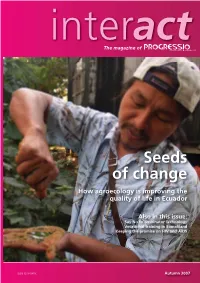

Interact Autumn 2007 Contents Editorial 6 3 First Person: Growing Together

interact The magazine of Seeds of change How agroecology is improving the quality of life in Ecuador Also in this issue: Say No to Terminator Technology Vocational training in Somaliland Keeping the promise on HIV and AIDS ISSN 1816-045X Autumn 2007 interact Autumn 2007 Contents editorial 6 3 first person: growing together Seeds of change 4 news: speaking out on Zimbabwe I hope you will read this issue of Interact and be 6 agenda: the quality of life inspired. Because I was. By the people of Ecuador who are standing up to the colonisation of their insight: seeds of change country – their natural resources, their culture and traditions – by multinational companies, A better living from the land international institutions and global capital. By the 7 Alternatives for food security in Ecuador 10 Progressio development workers like José Jiménez, Alex Amézquita, Rogasian Massue and Chris Nyamandi, whose commitment to their 10 You are what you eat Changing the way food is produced work – and to the people they work with – shines through in the articles they have written for you voices to read. Back to their roots But most of all, I hope that what you read here 12 Farmers in Ecuador talk about agroecology will inspire you to action. Because the people throughout the world struggling to take control action of their lives, in the face of the challenges of poverty, need our support. Whether it is practical 14 Say No to Terminator Technology action such as adding your voice to Progressio’s Join Progressio’s seedsaver campaign campaign against Terminator technology, or financial support for the Progressio development viewpoint workers in countries from East Timor to Ecuador, what you do can make – and does make – a real difference. -

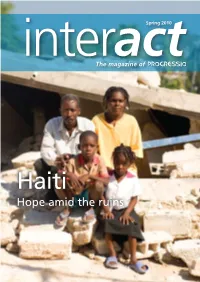

Interact Spring 2010

interactSpring 2010 The magazine of Haiti Hope amid the ruins contents agenda Charity must be underpinned by Cover: The Vilme family, justice, says Progressio’s Executive Sonnel and Marie Rose with Director Christine Allen their children Walker and Marie Walkine, pictured in the Mariani district of interact Port-au-Prince, Haiti, five days after the earthquake. Hope amid the ruins Photo: Moises Saman/Panos The recent earthquake in Haiti was a tragedy of epic 4 insight spring 2010 • proportions. Yet it also showed us the capacity of human hope amid the ruins beings for generosity. There was an enormous response to our own appeal and for that we thank you. 8 action Haitians ‘locked out’ As the immediate emergency efforts give way to plans and action on longer-term measures, the people of Haiti 10 voices remind us that our response can never only be a matter Romero’s legacy of charitable giving. It must also be about justice, and tackling the structures that cause and perpetuate poverty. 12 viewpoint prisoners in Zimbabwe Someone who lived out that dual commitment to charity and justice was Oscar Romero: an Archbishop who lived 14 Q&A a simple life and who genuinely loved, listened to and Dahir Korrow Issak spoke out on behalf of the poor of El Salvador. He showed us how the church can truly be a church of the poor, 16 reflection by taking sides, denouncing injustice and being a living Romero’s prophetic message witness to a new hope for the people. That question of justice, of structures, of the need for a policy response to poverty is doubtless in our minds here in the UK as a General Election approaches. -

Interact Spring 2008 Contents

issue 019 3/4/08 17:50 Page 1 interact The magazine of Changing lives How Progressio development workers help change people’s lives Also in this issue: Illegal logging in Ecuador Women’s roles in Somaliland A question of faith in Yemen ISSN 1816-045X Spring 2008 issue 019 3/4/08 17:50 Page 2 interact Spring 2008 Contents editorial 4 3 first person Changing lives 4 news In 2005, on a visit to Peru and Ecuador, I met 6 agenda Progressio development worker Jaime Torres (pictured on the front of this Interact). I wrote insight: changing lives at the time (http://incatrials.blogspot.com/): ‘Jaime is a young Colombian who gave up a prestigious job in Bogotá to come to a rural Breaking new ground community to teach farmers to use computers. 7 Patrick Reilly in Somaliland If that sounds stupid, it’s not. It’s really amazing. There are 13,000 farms in the district Outside the comfort zone and they all rely on water distributed through a 8 Michelle Lowe in Ecuador complex system of irrigation channels. The water is controlled by local irrigation councils, Discovery and renewal which need to know how much water to send 9 Charlie Smith in Peru where, and when. The irrigation councils have to apply to the government to get the water, Growing stronger 11 so need to know how much water is needed, 10 Sanne te Pas in El Salvador and when. The farmers need to know which crops to plant and when, so that they can get Playing our part the best prices, and be sure they will have 11 Stephanie Boyd in Peru enough water for the crops to grow… ‘Jaime has devised a database system to The hurricane that brings good collate all the information, and a wireless 13 Jane Freeland in Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast internet system to make it accessible to the farmers and the irrigation councils… [He has] viewpoint faced problems head on, solved them creatively, and created a sustainable system that provides a simple, workable solution to a Finding yourself problem faced by an entire district of farms. -

Interact Summer 2006

issue 012 13/7/06 16:47 Page 1 interact The magazine of The future in our hands Universities by the people, for the people Also in this issue: Capacity building in Yemen Food sovereignty in Nicaragua Water management in Peru ISSN 1816-045X Summer 2006 issue 012 13/7/06 16:47 Page 2 interact summer 2006 Contents /Progressio Nick Sireau editorial 6 3 first person: Tsitsi Choruma The future in our 4 voices: struggles and victories hands 6 news: churches oppose Terminator Educationalists would no doubt protest that times insight: the future in our hands have changed. But my own experience of education was of being told what I needed to know, and of being taught to think what the 8 Learning wisdom people in charge wanted me to think. An indigenous university in Ecuador 10 Imagine how much worse this is when what you 10 From guns to pens are told, and how you are told to think, does not Somaliland’s first ever university conform to your own reality. I believe that challenging the given way of viewpoint thinking can enable people to better understand 12 their own reality – and perhaps, to see more clearly their own future. 12 The chance of a lifetime Capacity building in Yemen This edition of Interact examines how people are thinking outside the boxes provided for them. The insight section tells the stories of two pioneering analysis universities: one that seeks to build on the wisdom of the indigenous peoples of Ecuador; another that seeks to build a future for a country, 13 Why we are hungry Somaliland, being built by its people. -

Latin America Solidarity Centre Lnformation Pack

R8915 Folder Inserts New TABS 28/1/08 3:20 pm Page 1 Latin America Solidarity Centre lnformation Pack An information and learning resource providing an introduction to Latin America This pack was first produced in 2006 Updates are available on www.lasc.ie Funding was kindly provided by DCI and Trocaire LASC 5, Merrion Row, Dublin 2, Ireland Phone: +353-1-6760435 Fax: +353-1-6621784 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.lasc.ie R8915 Folder Inserts New TABS 28/1/08 3:20 pm Page 2 What is LASC? The Latin America Solidarity Centre (LASC) is a non-governmental organisation founded in 1996. LASC is an initiative for cultural promotion, development education and campaigning solidarity, linking Ireland and Latin America. Vision LASC believes in a Latin America and an Ireland based on equality, social justice and an equal expression of cultural, social, political and economic rights for all human beings. Mission LASC’s mission is to challenge the current economic and social injustices in Latin America and Ireland by engaging in public awareness raising, education, information exchanges and campaigns in solidarity with the people of Latin America. What does LASC do? ✱ Offers solidarity to Latin America social movements ✱ Co-ordinates Latin America Week ✱ Runs courses in Latin American Development Issues ✱ Runs courses in Latin American Spanish ✱ Organises public meetings & talks ✱ Runs a resource centre, email news list and website ✱ Supports sub-groups campaigning on specific issues ✱ Organises cultural events Get involved in LASC: Become a member: Become a member of LASC for €25 or €10 (unwaged). Send your details (name, address, phone number & email) with a cheque/postal order to: LASC, 5, Merrion Row, Dublin 2. -

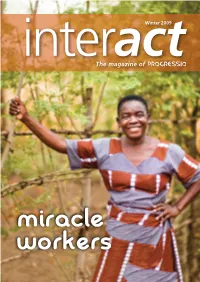

Interact Winter 2009

interactWinter 2009 The magazine of miracle workers contents agenda Our actions must speak as loud Cover: Gladys Gogwe (53), a as our words, writes Progressio’s small-scale farmer in southern Executive Director Christine Allen Malawi, who has been growing Jatropha, Neem and Moringa trees to boost her interact income and conserve and enrich the soil. See page 4 for miracle workers the full story. Photo: Marcus Perkins/ The Progressio people who went to Copenhagen for the Progressio winter 2009 • climate change summit were not the rich and powerful in the traditional sense. But our delegation included 4 insight representatives from our partner organisations, who bring miracle workers a wealth of experience of the reality of living vulnerable to climate and weather changes. The delegation therefore 8 action represented powerful voices – the voices of those who are climate change poor and marginalised around the world, but nevertheless powerful because they speak of truth, from experience. 10 voices rights and freedoms The individual, small-scale level can often feel very far from ‘high-level’ policy and decision-making. At Progressio, 12 viewpoint we seek to make the connections by rooting our policy women in Honduras analysis in our direct experience with people who are poor and marginalised – and by bringing their voices to the 14 Q&A negotiating table. Monika Galeano Small voices being heard loudly is something of a theme 16 reflection for this edition of Interact. Whether it’s the experience the lives of all living beings and potential of small-scale farmers being heard amidst the clamour of large-scale food production, or the voices of women standing up for their rights, we are seeking to make sure we can amplify and support the voices of people being heard where it matters. -

Thirsting for Justice “Defending the Global Water Commons”

R9490 L.A.W. Magazine 30/4/07 8:10 AM Page 1 ***LATIN AMERICA WEEK 2007 (programme inside) 15-21 APRIL*** THIRSTING FOR JUSTICE “DEFENDING THE GLOBAL WATER COMMONS” © water for people Water wars: Exploring the 20th-century neo-liberal context and the struggle against water privitisation. Voices of resistance: From North and South, Latin America and Ireland. Global challenges Water and Gender. Water and Youth. Water and Debt. Water and Culture. Water and Environment... Latin America Solidarity Centre 01 6760435 [email protected] www.lasc.ie LASC gratefully acknowledges funding from Irish Aid & TRÓCAIRE L.A.W. 1 R9490 L.A.W. Magazine 30/4/07 8:10 AM Page 2 LATIN AMERICA SOLIDARITY L.A.W. 2007 concentrates on the CENTRE (LASC) lessons that we here in Ireland can TABLE OF CONTENTS 5, Merrion Row, Dublin 2 learn from the Latin American Tel: + 353 1 6760435 struggles for access to water. How did Water Wars – The Neoliberal Background 3 Fax: + 353 1 6621784 some of our brothers and sisters in E-mail: [email protected] Latin America manage to regain Enclosing the Water Commons 5 Website: www.lasc.ie control of their water services in the face of neoliberalism? How did they Water struggles in Latin America 7 manage to throw some of the most EDITORIAL powerful water corporations in the The record of water privatization in developing countries 8 On behalf of LASC I’m delighted to world out of their cities? present you with the programme for These are success stories – or are they? Water struggles in Ireland Latin America Week 2007, ‘Thirsting We look forward to hearing what the for Justice: Defending the Global situation is in Bolivia after the Water Beating the water charges in Dublin 9 Water Commons’.