Tuesday, January 2, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

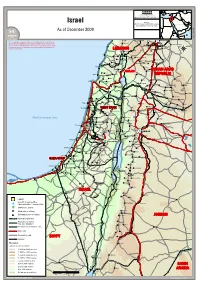

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

Bimt Seminar Handout

Bringing the Bible to LifeSeminar Physical Settings of the Bible Seminar Topics Session I: Introduction - “Physical Settings of the Bible” Session II: “Connecting the Dots” - Geography of Israel Session III: Archaeology & the Bible Session IV: Life & Ministry of Jesus Session V: Jerusalem in the Old Testament Session VI: Jerusalem in the Days of Jesus Session VII: Manners & Customs of the Bible Goals & Objectives • To gain a new and exciting “3-D” perspective of the land of the Bible. • To begin understanding the “playing board” of the Bible. • To pursue the adventure of “connecting the dots” between the ancient world of the Bible and Scripture. • To appreciate the context of the stories of the Bible, including the life and ministry of Jesus. • To grow in our walk of faith with the God of redemptive history. 2 Bringing the Bible to Life Seminar About Biblical Israel Ministries & Tours Biblical Israel Ministries & Tours (BIMT) was created 25 years ago (originally called Biblical Israel Tours) out of a passion for leading people to a personalized study tour experience of Israel, the land of the Bible. The ministry expanded in 2016. BIMT is now a support-based evangelical support-based non-profit 501c3 tax-exempt ministry dedicated to helping people “connect the dots” between the context of the ancient world of the Bible and Scripture. The two-fold purpose of BIMT is: 1. Leading highly biblical study-discipleship tours to Israel and other lands of the Bible, and 2. Providing “Physical Settings of the Bible” teaching and discipleship training for churches and schools. It is our prayer that BIMT helps people to not only grow in a deeper understanding (e.g. -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Sociology and Anthropology 1998 Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel Sarah VanSickle '98 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/socanth_honproj Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation VanSickle '98, Sarah, "Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel" (1998). Honors Projects. 19. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/socanth_honproj/19 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by Faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Trade and Commerce At Sepphoris, Israel Sarah VanSickle 1998 Honors Research Dr. Dennis E. Groh, Advisor I Introduction Trade patterns in the Near East are the subject of conflicting interpretations. Researchers debate whether Galilean cities utilized trade routes along the Sea of Galilee and the Mediterranean or were self-sufficient, with little access to trade. An analysis of material culture found at specific sites can most efficiently determine the extent of trade in the region. If commerce is extensive, a significant assemblage of foreign goods will be found; an overwhelming majority of provincial artifacts will suggest minimal trade. -

Occupied Palestinian Territory (Including East Jerusalem)

Reporting period: 29 March - 4 April 2016 Weekly Highlights For the first week in almost six months there have been no Palestinian nor Israeli fatalities recorded. 88 Palestinians, including 18 children, were injured by Israeli forces across the oPt. The majority of injuries (76 per cent) were recorded during demonstrations marking ‘Land Day’ on 30 March, including six injured next to the perimeter fence in the Gaza Strip, followed by search and arrest operations. The latter included raids in Azzun ‘Atma (Qalqiliya) and Ya’bad (Jenin) involving property damage and the confiscation of two vehicles, and a forced entry into a school in Ras Al Amud in East Jerusalem. On 30 occasions, Israeli forces opened fire in the Access Restricted Area (ARA) at land and sea in Gaza, injuring two Palestinians as far as 350 meters from the fence. Additionally, Israeli naval forces shelled a fishing boat west of Rafah city, destroying it completely. Israeli forces continued to ban the passage of Palestinian males between 15 and 25 years old through two checkpoints controlling access to the H2 area of Hebron city. This comes in addition to other severe restrictions on Palestinian access to this area in place since October 2015. During the reporting period, Israeli forces removed the restrictions imposed last week on Beit Fajjar village (Bethlehem), which prevented most residents from exiting and entering the village. This came following a Palestinian attack on Israeli soldiers near Salfit, during which the suspected perpetrators were killed. Israeli forces also opened the western entrance to Hebron city, which connects to road 35 and to the commercial checkpoint of Tarqumiya. -

The Truth About the Struggle of the Palestinians in the 48 Regions

The truth about the struggle of the Palestinians in the 48 regions By: Wehbe Badarni – Arab Workers union – Nazareth Let's start from here. The image about the Palestinians in the 48 regions very distorted, as shown by the Israeli and Western media and, unfortunately, the .Palestinian Authority plays an important role in it. Palestinians who remained in the 48 regions after the establishment of the State of Israel, remained in the Galilee, the Triangle and the Negev in the south, there are the .majority of the Palestinian Bedouin who live in the Negev. the Palestinians in these areas became under Israeli military rule until 1966. During this period the Palestinian established national movements in the 48 regions, the most important of these movements was "ALARD" movement, which called for the establishment of a democratic secular state on the land of Palestine, the Israeli authorities imposed house arrest, imprisonment and deportation active on this national movement, especially in Nazareth town, and eventually was taken out of .the law for "security" reasons. It is true that the Palestinians in the 48 regions carried the Israeli citizenship or forced into it, but they saw themselves as an integral part of the Palestinian Arab people, are part and an integral part of the Palestinian national movement, hundreds of Palestinians youth in this region has been joined the Palestinian .resistance movements in Lebanon in the years of the sixties and seventies. it is not true that the Palestinians are "Jews and Israelis live within an oasis of democracy", and perhaps the coming years after the end of military rule in 1966 will prove that the Palestinians in these areas have paid their blood in order to preserve their Palestinian identity, in order to stay on their land . -

Liliislittlilf Original Contains Color Illustrations

liliiSlittlilf original contains color illustrations ENERGY 93 Energy in Israel: Data, Activities, Policies and Programs Editors: DANSHILO DAN BAR MASHIAH Dr. JOSEPH ER- EL Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure Jerusalem, 1993 Front Cover: First windfarm in Israel - inaugurated at the Golan Heights, in 1993 The editors wish to thank the Director-General and all other officials concerned, including those from Government companies and institutions in the energy sector, for their cooperation. The contributions of Dr. Irving Spiewak, Nissim Ben-Aderet, Rachel P. Cohen, Yitzhak Shomron, Vladimir Zeldes and Yossi Sheelo (Government Advertising Department) are acknowledged. Thanks are also extended to the Eilat-Ashkelon Pipeline Co., the Israel Electric Corporation, the National Coal Supply Co., Mei Golan - Wind Energy Co., Environmental Technologies, and Lapidot - Israel Oil Prospectors for providing photographic material. TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW 4 1. ISRAEL'S ENERGY ECONOMY - DATA AND POLICY 8 2. ENERGY AND PEACE 21 3. THE OIL AND GAS SECTOR 23 4. THE COAL SECTOR 29 5. THE ELECTRICITY SECTOR 34 6. OIL AND GAS EXPLORATION. 42 7. RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION 46 8. ENERGY CONSERVATION 55 9. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY. 60 OVERVIEW Since 1992. Israel has been for electricity production. The latter off-shore drillings represer involved, for the first time in its fuel is considered as one of the for sizable oil findings in I: short history, in intensive peace cleanest combustible fuels, and may Oil shale is the only fossil i talks with its neighbors. At the time become a major substitute for have been discovered in Isi this report is being written, initial petroleum-based fuels in the future. -

Why Visiting Israel?)

1 Ricardo Motta Pinto Coelho & Consultores em Recursos Hídricos www.rmpcecologia.com [email protected] +5531 3517 9793 2 1.- Introdução (Introduction) A maioria dos brasileiros aprende ainda na escola elementar que esse é um país das infinitas águas. Afinal, temos a maior bacia hidrográfica do mundo, ou seja, o complexo sistema fluvial do rio Amazonas. E não é só isso. Outro grande rio, em escala mundial, o rio Paraná nasce e corre uma boa extensão em território brasileiro. A esses dois sistemas fluviais, de importância global, o país ainda dispõe de vários outros grandes rios (com mais de 1.000 km de extensão), várias províncias ou distritos lacustres, o pantanal, uma das maiores wetlands de toda a biosfera. Esses superlativos lotam os livros das escolas elementares brasileiras. No entanto, essa realidade esconde uma outra, menos ufanista. O Brasil sofre com a crescente falta de água. E não é na Amazônia, nem na bacia do rio Paraná. A água está escassa nas maiores cidades do país, espalhadas pelo planalto central e pelo litoral Atlântico. Nessas regiões, onde se concentra a maior parte dos 250 milhões de brasileiros, graças às mudanças climáticas globais, ao mau uso das águas, e à falta de uma boa governança das águas está faltando água! English Most Brazilians still learn in elementary school that this is a country of infinite waters. After all, we have the largest river basin in the world, that is, the complex river system of the Amazon River. This is not all. Another great river, on a world scale, the Paraná River is born and runs a good extension in Brazilian territory. -

Palestine About the Author

PALESTINE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Professor Nur Masalha is a Palestinian historian and a member of the Centre for Palestine Studies, SOAS, University of London. He is also editor of the Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. His books include Expulsion of the Palestinians (1992); A Land Without a People (1997); The Politics of Denial (2003); The Bible and Zionism (Zed 2007) and The Pales- tine Nakba (Zed 2012). PALESTINE A FOUR THOUSAND YEAR HISTORY NUR MASALHA Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History was first published in 2018 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Copyright © Nur Masalha 2018. The right of Nur Masalha to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by seagulls.net Index by Nur Masalha Cover design © De Agostini Picture Library/Getty All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑272‑7 hb ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑274‑1 pdf ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑275‑8 epub ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑276‑5 mobi CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 1. The Philistines and Philistia as a distinct geo‑political entity: 55 Late Bronze Age to 500 BC 2. The conception of Palestine in Classical Antiquity and 71 during the Hellenistic Empires (500‒135 BC) 3. -

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Research and writing: Michal Belikoff and Safa Ali Agbaria Editing: Shirley Racah Steering committee: Samah Elkhatib-Ayoub, Ron Gerlitz, Azar Dakwar, Mohammed Khaliliye, Abed Kanaaneh, Jabir Asaqla, Ghaida Rinawie Zoabi, and Shirley Racah Critical review and assistance with research and writing: Ron Gerlitz and Shirley Racah Academic advisor: Dr. Nahum Ben-Elia Co-directors of Sikkuy’s Equality Policy Department: Abed Kanaaneh and Shirley Racah Project director for Injaz: Mohammed Khaliliye Hebrew language editing: Naomi Glick-Ozrad Production: Michal Belikoff English: IBRT Jerusalem Graphic design: Michal Schreiber Printed by: Defus Tira This pamphlet has also been published in Arabic and Hebrew and is available online at www.sikkuy.org.il and http://injaz.org.il Published with the generous assistance of: The European Union This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Sikkuy and Injaz and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The Moriah Fund UJA-Federation of New York The Jewish Federations of North America Social Venture Fund for Jewish-Arab Equality and Shared Society The Alan B. -

United Nations Conciliation.Ccmmg3sionfor Paiestine

UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION.CCMMG3SIONFOR PAIESTINE RESTRICTEb Com,Tech&'Add; 1 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH APPENDIX J$ NON - JlXWISHPOPULATION WITHIN THE BOUNDARXESHELD BY THE ISRAEL DBFENCEARMY ON X5.49 AS ON 1;4-,45 IN ACCORDANCEWITH THE PALESTINE GOVERNMENT VILLAGE STATISTICS, APRIL 1945. CONTENTS Pages SUMMARY..,,... 1 ACRE SUB DISTRICT . , , . 2 - 3 SAPAD II . c ., * ., e .* 4-6 TIBERIAS II . ..at** 7 NAZARETH II b b ..*.*,... 8 II - 10 BEISAN l . ,....*. I 9 II HATFA (I l l ..* a.* 6 a 11 - 12 II JENIX l ..,..b *.,. J.3 TULKAREM tt . ..C..4.. 14 11 JAFFA I ,..L ,r.r l b 14 II - RAMLE ,., ..* I.... 16 1.8 It JERUSALEM .* . ...* l ,. 19 - 20 HEBRON II . ..r.rr..b 21 I1 22 - 23 GAZA .* l ..,.* l P * If BEERSHEXU ,,,..I..*** 24 SUMMARY OF NON - JEWISH'POPULATION Within the boundaries held 6~~the Israel Defence Army on 1.5.49 . AS ON 1.4.45 Jrr accordance with-. the Palestine Gp~ernment Village ‘. Statistics, April 1945, . SUB DISmICT MOSLEMS CHRISTIANS OTHERS TOTAL ACRE 47,290 11,150 6,940 65,380 SAFAD 44,510 1,630 780 46,920 TJBERIAS 22,450 2,360 1,290 26,100 NAZARETH 27,460 Xl, 040 3 38,500 BEISAN lT,92o 650 20 16,590 HAXFA 85,590 30,200 4,330 120,520 JENIN 8,390 60 8,450 TULJSAREM 229310, 10 22,320' JAFFA 93,070 16,300 330 1o9p7oo RAMIIEi 76,920 5,290 10 82,220 JERUSALEM 34,740 13,000 I 47,740 HEBRON 19,810 10 19,820 GAZA 69,230 160 * 69,390 BEERSHEBA 53,340 200 10 53,m TOT$L 621,030 92,060 13,710 7z6,8oo . -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District.