Brevard College Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Single Point of Contact on Campuses for Unaccompanied/Homeless Youth

Single Point of Contact on Campuses for Unaccompanied/Homeless Youth College Contact Name Location Phone # Contact email address Fax # Alamance Community College Sabrina DeGain Gee Building First Floor G 124 336-506-4161 [email protected] 336-506-4264 Appalachian State Alan Rasmussen, Interim University Office of the Dean of Students 838-262-8284 [email protected] 828-262-4997 Dean of Students Asheville-Buncombe Technical Heather Pack, Director of Bailey Building; 340 Victoria Road, 828-398-7900 [email protected] 828-251-6718 Community College Student Support Services Asheville, NC 28801 Barton College Thomas Welch, Dir FA Harper Room #118 252-399-6371 [email protected] 252-399-6531 Beaufort County Community College Kimberly Jackson Building 9 Room 925 252-940-6252 [email protected] 252-940-6274 Div. of Student Affairs, Bennett Mrs. Kimberly Drye-Dancy Bennett College College, 900 East Washington St, 336-517-2298 [email protected] Greensboro, NC 27401 Bladen Community College J. Carlton Bryan Bldg. 8 Rm 4 910-879-5524 [email protected] 910-879-5517 Blue Ridge Community College Kirsten Hobbs SINK 137 828-694-1693 [email protected] 828-694-1693 Financial Aid Office, Beam David L. Volrath, Director of Administration Building; One Brevard College Admissions & Financial Aid/ 828-884-8367 [email protected] 828-884-3790 Brevard College Drive, DSO Brevard, NC 28712 Brunswick Community College Julie Olsen, Director of Disability Resources and ACE Lab Building A, office 229 910-755-7338 [email protected] 910-754-9609 Student Life Cabarrus College of Valerie Richard- Financial 401 Medical Park Drive 704-403-3507 [email protected] 704-403-2077 Health Sciences Aid Concord, NC 28025 Caldwell Community College and Counseling and Advisement Technical Institute Shannon Brown Services, Building F. -

The Clarion, Vol. 86, Issue #24, March 17, 2021

Volume 86, Issue 24 Web Edition SERVING BREVARD COLLEGE SINCE 1935 March 17, 2021 BC’s cans for car wash event Last Sunday, there was a special charity car wash on the Brevard College campus called the “Cans for Car Wash.” On March 14, 2021 from 11:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m., anyone could bring in cans to donate and, in return, get a free car wash. The event was open to students, faculty and staff. Photo from WLOS The event took place behind the Porter Streets being blocked off in Downtown Brevard, on Sunday. Center and had a very simple premise. Bring in five or more cans of soup, pasta or similar products, and the hosts would wash your car in exchange. The cans were later donated to Bomb threats in local charities. There was plenty of fun music playing along with many helpers there. The BC Serves group hosting the event received downtown Brevard about 20-30 cans that day. If they ever do this persons were, and find out where they were By Margaret Correll again, make sure you have cans to bring in; Editor in Chief coming from on this.” they go to a good cause, and stuff like this Brevard College, just a few blocks away The small, downtown of Brevard, NC, should be done more often. experienced a bomb threat on Sunday, March from the scene, was notified by Stanley 14, 2021. This threat caused major shutdowns Jacobsen, Director of Safety and Security and —Jackson Inglis of the city and increased police presence in Risk Management, of the event taking place. -

FY 2005 Title III and Title V Eligible Institutions (PDF)

Title III and Title V Eligibility FY 2005 Eligible Institutions Group 1 STATE INSTITUTION CITY AK Sheldon Jackson College Sitka AK University of Alaska at Southeast Sitka Campus Sitka AK University of Alaska Fairbanks Bristol Bay Dillingham AK University of Alaska Fairbanks Chukchi Campus Kotzebue AK University of Alaska Fairbanks Kuskokwim Campus Bethel AK University of Alaska Fairbanks Northwest Campus Nome AL Alabama Southern Community College Monroeville AL Athens State University Athens AL Bevill State Community College Sumiton AL Enterprise-Ozark Community College Enterprise AL Faulkner State Community College Bay Minette AL Faulkner University Montgomery AL George C. Wallace Community College Dothan AL George C. Wallace State Community College Hanceville AL John C. Calhoun State Community College Decatur AL Lurleen B. Wallace Community College Andalusia AL Northeast Alabama Community College Rainsville AL Snead State Community College Boaz AL Southern Community College Tuskegee AL Troy State University Troy AL Troy State University Dothan Dothan AL Troy State University Montgomery Montgomery AL University of North Alabama Florence AR Arkansas Northeastern College Blytheville AR Arkansas State University Beebe Beebe AR Arkansas Technical University Russellville AR Cossatot Community College of the University of Arkansas De Queen AR Mid-South Community College West Memphis AR National Park Community College at Hot Springs Hot Springs AR North Arkansas College Harrison AR Phillips County Community College of the University of Arkansas -

United Methodist Dollars for Scholars Scholarship, ONLINE APPLICATION, Not Both

HOW TO APPLY DEADLINE: March 1, 2019 United Methodist Applications will be accepted beginning January 2, 2019 for the 2019-2020 Dollars for scholars academic year. The application and all required documents must be postmarked scholarship application no later than March 1, 2019. (or June 1, 2019 for students planning to For 2019-2020 Academic Year enroll in a 2-year college only) 1. Complete in full. Every question must be answered and all sections of the form must be completed; please type or print legibly. Review the provided Application Check List before sending in your materials. 2. Applications must be postmarked by the deadline date of March 1, 2019 (June 1, 2019 for students planning BASIC CRITERIA FOR ELIGIBILITY to enroll in a two-year college only). 3. SUBMIT EITHER PAPER OR To be eligible for a United Methodist Dollars for Scholars scholarship, ONLINE APPLICATION, not both. you must meet the following eligibility requirements: Submit online at umhef.org. You may also download a PDF, fill it out • You must be an active, full member of The United Methodist Church electronically then print and sign for at least one year prior to applying. before mailing. Applicant will be • You must be enrolled or planning to enroll in a full-time degree considered for only one award from program (graduate or undergraduate) at a United Methodist-related UMHEF during an academic year. college, university, or seminary in the United States. • Doctoral (Ph.D.) candidates are not eligible at this time. 4. A check for $1,000 payable to UMHEF from the sponsoring church (no personal checks) must be mailed How dollars for scholars works with the completed application. -

Bennett College Brevard College Greensboro College High Point University Pfeiffer University Western North Carolina Conference

REQUIREMENTS 1. All applicants must apply in writing to 6. All applicants are to be interviewed the Chair of the Scholarship Committee. each year by the Scholarship Committee, or be interviewed by a 2. All applicants must be members of person selected by the Chair of the the United Methodist Church and reside Scholarship Committee, prior to granting within the bounds of the Western North scholarships. Interviews will be held in Carolina Conference. Scholarship the spring. recipients shall pursue an academic course in one of the five United 7. No applicant will be considered Methodist-supported colleges or until all requirements are met. A universities in the Western North small, non-returnable picture attached to Bennett College Carolina Conference. the application will be helpful to the Brevard College Scholarship Committee. All applications Greensboro College 3. All applicants must have references are due by March 1 each year. from the following people: The High Point University applicant’s pastor, a faculty member of Pfeiffer University the school last attended, a peer group Additional information and person, and a business or professional application forms may be obtained from: person who knows the applicant through some experience outside the church. Forms will be provided. Cathy McCauley WNCC UMW Scholarship Chairperson 4. All applicants recently graduated 6835 Farmingdale Dr. Apt. A must supply a transcript of this high Charlotte, NC 28212 school record. In the case of a second- Phone: 704-965-6566 cell career applicant who has not been in Email: [email protected] school recently, a transcript will not be required. 5. -

The Clarion, Vol. 86, Issue #29, April 21, 2021

Volume 86, Issue 29 Web Edition SERVING BREVARD COLLEGE SINCE 1935 April 21, 2021 Graduation update Another graduation update for Brevard College graduates, senior hooding will be taking place on the day of graduation (May 8) during the commencement ceremony. According to the Commencement Team, some aspects of the Baccalaureate ceremony have been taken and incorporated into the graduation ceremony. Students and their chosen faculty member will complete the hooding process as their Courtesy of USA Today name is called and then will proceed to walk Capsized boat on the Louisiana Coast. across the stage to receive their diploma followed by pictures. Students are reminded that they will be receiving a diploma holder, without the actual diploma inside. Due to the ceremony being “rain or shine”, diplomas will be dispersed by mail. Boat capsized Seniors are also reminded that pinning will be taking place the evening before graduation (May 7) following the commencement rehearsals and the class photo. The first commencement rehearsal for those graduating off the coast of at 8 a.m. will take place at 4:30 p.m., followed by a class photo. The second rehearsal for those graduating at noon will begin at 5:30 p.m. while senior pinning number one is taking place. The second senior pinning Coast Guard boats and aircraft have covered rescued another two people. Louisiana ceremony will take place at 6:30 p.m. an area larger than the state of Rhode Island to One worker was found dead on the surface Graduating students are encouraged to search for 12 people still missing Wednesday, of the water, Watson said at a news conference keep up with updates from the Brevard April 14, off the Louisiana coast after their Wednesday. -

FORWARD THINKERS WHOSE IDEAS and ACCOMPLISHMENTS INSPIRE and IMPROVE OUR LIVES the Opposite VOLUME 88 ISSUE NO

Ohio Wesleyan Magazine OWU VOLUME 88 ISSUE NO. 3 r FALL 2011 Creativity FORWARD THINKERS WHOSE IDEAS AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS INSPIRE AND IMPROVE OUR LIVES The Opposite VOLUME 88 ISSUE NO. 3 r FALL 2011 of Ordinary www.owualumni.com Ohio Wesleyan Alumni Online Community Editor Pamela Besel Class Notes Editor Andrea Misko Strle ’99 OWU [email protected] Ohio Wesleyan Magazine Designer Sara Stuntz FEATURES // Contributing Writers Pam Besel Cole Hatcher Gretchen Hirsch 12 The Angel in the Marble Kelsey Kerstetter ’12 What is creativity and how is it nourished and unleashed? Four Ohio Wesleyan Linda Miller O’Horo ’79 professors weigh in on teaching and learning ‘beyond the syllabus.’ Michelle Rotuno-Johnson ’12 Andrea Misko Strle ’99 Amanda Zeichel ’09 18 Man Behind the Camera Contributing Photographers Merging innovative artistic talent and passion with business savvy in today’s Sara Blake Doug Martin Pam Burtt Taylor Rivkin ’14 flourishing online and digital communications realms, Tom Powel ’79 is John Holliger Kelsey Ullom ’14 revolutionizing how works of fine art are photographed, exhibited, sold, and archived Paul Molitor Brittany Vickers ’13 for the world to admire. Director of Marketing and Communication Mark Cooper Marketing and Communication Office 25 Getting His Slice of the Pie (740) 368-3335 Glenn Mueller ’77 has come a long way, from the teenager who remodeled pizza Director of Alumni Relations shops, to the President and CEO of RPM, the largest franchise of Domino’s Pizza in Brenda DeWitt the country. Idea sharing and responding to consumer needs have everything to do Alumni Relations Office with that success. -

2010 Catalog

BREVARD COLLEGE 2009 – 2010 Catalog BREVARD COLLEGE CATALOG 2009-2010 This catalog is designed to assist prospective and current students, parents, and high school counselors, as well as the faculty, staff, alumni, and friends of the College. It portrays the College in all its complexity, it purpose and history, its individual faculty members and the classes they teach, its leadership opportunities and recreational programs, its campus facilities and its surrounding communities, its traditions and regulations, and the financial aid programs that make it possible for students from every economic background to enjoy the benefits of a Brevard College education. EQUAL OPPORTUNITY POLICY Brevard College does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, sexual orientation, age, disability, or veteran’s status and prohibits such discrimination by its students, faculty and staff. Students, faculty, and staff are assured of participation in college programs and in use of facilities without such discrimination. The College also complies with all applicable federal and North Carolina statutes and regulations prohibiting unlawful discrimination. All members of the student body, faculty, and staff are expected to assist in making this policy valid in fact. NOTICE: INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO REVISION Information in this catalog is current through June 2009. Brevard College reserves the right to change programs of study, academic requirements, fees, and College policies at any time, in accordance with established procedures, without prior notice. An effort will be made to notify persons who may be affected. The provisions of this catalog are not to be regarded as an irrevocable contract between the student and the College. -

Comparison Group 2 Details

NSSE 2012 Selected Comparison Groups Regent University Comparison Group 2 Details This report displays the 2012 comparison group 2 institutions for Regent University. The institutions listed below are represented in the 'Southeast' column of the Respondent Characteristics, Mean Comparisons, Frequency Distributions, and Benchmark Comparisons reports. HOW GROUP WAS SELECTED You selected specific institutions from a list of NSSE 2012 participants. SELECTED COMPARISON GROUP CRITERIA a Basic 2010 Carnegie Classification(s): Carnegie - Undergraduate Instructional Program(s): Carnegie - Graduate Instructional Program(s): Carnegie - Enrollment Profile(s): Carnegie - Undergraduate Profile(s): Carnegie - Size and Setting(s): Sector(s) (public/private): Undergraduate enrollment(s): Locale(s): Geographic Region(s): State(s): Barron's admissions selectivity ratings(s): COMPARISON GROUP 2 INSTITUTIONS Institution Name City State Abilene Christian University Abilene TX Appalachian State University Boone NC Auburn University Auburn University AL Auburn University at Montgomery Montgomery AL Augusta State University Augusta GA Austin Peay State University Clarksville TN Barry University Miami FL Barton College Wilson NC Baylor University Waco TX Bellarmine University Louisville KY Belmont Abbey College Belmont NC Belmont University Nashville TN Berry College Mount Berry GA Bethune Cookman University Daytona Beach FL Birmingham-Southern College Birmingham AL Bluefield College Bluefield VA a. See the Comparison Group Selection Criteria Codelist for code -

The Benefits of a College Education Are Within Reach for Your Child

College Is Affordable The benefits of a college education are within reach for your child CFNC.org/collegeworks A college degree can transform your child’s life in five important ways: 1. More security 2. Better health 3. Closer family 4. Stronger community 5. Greater wealth Talking to your child about staying in school and aiming for college is a good way to help him or her achieve a brighter future. Each extra year that your child stays in school will lead to higher earnings. And for most students who go to college, the increase in their lifetime earnings is far greater than the cost of their education. But greater wealth is not the only positive outcome of a college education. College provides a path to an overall fuller life. That’s why we want to show you that your family really can afford your child’s college education. College is affordable because of what is known as financial aid. Offered by the How do federal and state governments, colleges, and other sources, aid is available to families like everyone who needs it. Financial aid can significantly reduce the cost of college, even covering the entire cost of tuition and fees. yours afford Financial aid can also make paying for any small costs you may have to cover much college? easier to manage. It is important for you to know that most students pay far less than the high prices you hear about in the news. So nobody should ever rule out going to college based just on published prices! There are three types of financial aid that let you reduce and manage the cost of a college education. -

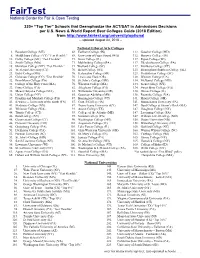

Test Optional Schools in the Top 100 U

FairTest National Center for Fair & Open Testing 320+ “Top Tier” Schools that Deemphasize the ACT/SAT in Admissions Decisions per U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges Guide (2018 Edition) from http://www.fairtest.org/university/optional -- updated August 24, 2018 -- National Liberal Arts Colleges 3. Bowdoin College (ME) 68. Earlham College (IN) 112. Goucher College (MD) 6. Middlebury College (VT) “Test Flexible” 68. University of Puget Sound (WA) 112. Hanover College (IN) 12. Colby College (ME) “Test Flexible” 71. Knox College (IL) 117. Ripon College (WI) 12. Smith College (MA) 71. Muhlenberg College (PA) 117. Elizabethtown College (PA) 18. Hamilton College (NY) “Test Flexible” 71. Wofford College (SC) 117. Marlboro College (VT) 21. Wesleyan University (CT) 76. Beloit College (WI) 123. Birmingham-Southern College (AL) 23. Bates College (ME) 76. Kalamazoo College (MI) 123. Presbyterian College (SC) 23. Colorado College (CO) “Test Flexible” 76. Lewis and Clark (OR) 128. Whittier College (CA) 32. Bryn Mawr College (PA) 76. St. John’s College (NM) 134. McDaniel College (MD) 33. College of the Holy Cross (MA) 76. Wheaton College (MA) 134. Siena College (NY) 33. Pitzer College (CA) 82. Allegheny College (PA) 134. Sweet Briar College (VA) 36. Mount Holyoke College (MA) 82. Willamette University (OR) 138. Illinois College (IL) 36. Union College (NY) 85. Gustavus Adolphus (MN) 138. Roanoke College (VA) 39. Franklin and Marshall College (PA) 87. Bennington College (VT) 141. Hiram College (OH) 41. Sewanee -- University of the South (TN) 87. Cornell College (IA) 141. Susquehanna University (PA) 41. Skidmore College (NY) 87. Transylvania University (KY) 147. Bard College at Simon’s Rock (MA) 41. -

Member Colleges & Universities

Bringing Colleges & Students Together SAGESholars® Member Colleges & Universities It Is Our Privilege To Partner With 427 Private Colleges & Universities April 2nd, 2021 Alabama Emmanuel College Huntington University Maryland Institute College of Art Faulkner University Morris Brown Indiana Institute of Technology Mount St. Mary’s University Stillman College Oglethorpe University Indiana Wesleyan University Stevenson University Arizona Point University Manchester University Washington Adventist University Benedictine University at Mesa Reinhardt University Marian University Massachusetts Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Savannah College of Art & Design Oakland City University Anna Maria College University - AZ Shorter University Saint Mary’s College Bentley University Grand Canyon University Toccoa Falls College Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Clark University Prescott College Wesleyan College Taylor University Dean College Arkansas Young Harris College Trine University Eastern Nazarene College Harding University Hawaii University of Evansville Endicott College Lyon College Chaminade University of Honolulu University of Indianapolis Gordon College Ouachita Baptist University Idaho Valparaiso University Lasell University University of the Ozarks Northwest Nazarene University Wabash College Nichols College California Illinois Iowa Northeast Maritime Institute Alliant International University Benedictine University Briar Cliff University Springfield College Azusa Pacific University Blackburn College Buena Vista University Suffolk University California