The Book As Instrument: Craft and Technique in Early Modern Practical Mathematics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

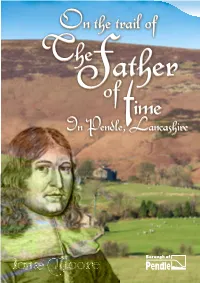

Jonas Moore Trail

1 The Pendle Witches He would walk the three miles to Burnley Grammar School down Foxendole Lane towards Jonas Moore was the son of a yeoman farmer the river Calder, passing the area called West his fascinating four and a half called John Moore, who lived at Higher White Lee Close where Chattox had lived. in Higham, close to Pendle Hill. Charged for crimes committed using mile trail goes back over 400 This was the early 17th century and John witchcraft, Chattox was hanged, alongside years of history in a little- Moore and his wife lived close to Chattox, the Alizon Device and other rival family members and known part of the Forest of Bowland, most notorious of the so called Pendle Witches. neighbours, on the hill above Lancaster, called The Moores became one of many families caught Golgotha. These were turbulent and dangerous an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. up in events which were documented in the times in Britain’s history, including huge religious It explores a hidden valley where there are world famous trial. intolerance between Protestants and Catholics. Elizabethan manor houses and evidence of According to the testimony of eighteen year Civil War the past going back to medieval times and old Alizon Device, who was the granddaughter of the alleged Pendle witch Demdike, John earlier. The trail brings to light the story of Sir Moore had quarrelled with Chattox, accusing her In 1637, at the age of 20, Jonas Moore was Jonas Moore, a remarkable mathematician of turning his ale sour. proficient in legal Latin and was appointed clerk and radical thinker that time has forgotten. -

De Keyser's Royal Hotel Limited

APPENDIX A Ibouee of Xorb6- Monday, May 10, 1920. THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL (on behalf of His Majesty) ....... Appellant AND DE KEYSER'S ROYAL HOTEL, LIMITED . Eespondents, Lords present : LORD DUNEDIN. LORD ATKINSON. LORD MOULTON. LORD SUMNER. LORD PARMOOR. JUDGMENT 1 LORD DUNEDIN : My Lords, it will be well that I should first set forth succinctly the facts which give rise to the present Petition, all the more that as regards them there is no real controversy between the parties. [His Lordship then stated ' the facts as set out at pp. I to 3, ante.] The relief asked was : (1) A declaration that your suppliants are entitled to payment of an annual rent so long as Your Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for the War Department or Your Majesty's Army Council or any other person or persons acting on Your Majesty's behalf continues in use and occupation of the said premises. (2) The sum of £13,520 lis. Id. for use and occupation of your suppliants' said premises by your suppliants' permission from the 8th day of May 1916 to the 14th day of February 1917. (4) A declaration that your suppliants are entitled to a fair rent for use and occupation by way of compensation under the Defence Act, 1842.' To this reply was made by the Attorney-General on ' behalf of His Majesty to the following effect : (7) No rent or compensation is by law payable to the suppliants in respect of the matters aforesaid or any of them either under the Defence Act, 1842, or at all. -

Recent Publications 1984 — 2017 Issues 1 — 100

RECENT PUBLICATIONS 1984 — 2017 ISSUES 1 — 100 Recent Publications is a compendium of books and articles on cartography and cartographic subjects that is included in almost every issue of The Portolan. It was compiled by the dedi- cated work of Eric Wolf from 1984-2007 and Joel Kovarsky from 2007-2017. The worldwide cartographic community thanks them greatly. Recent Publications is a resource for anyone interested in the subject matter. Given the dates of original publication, some of the materi- als cited may or may not be currently available. The information provided in this document starts with Portolan issue number 100 and pro- gresses to issue number 1 (in backwards order of publication, i.e. most recent first). To search for a name or a topic or a specific issue, type Ctrl-F for a Windows based device (Command-F for an Apple based device) which will open a small window. Then type in your search query. For a specific issue, type in the symbol # before the number, and for issues 1— 9, insert a zero before the digit. For a specific year, instead of typing in that year, type in a Portolan issue in that year (a more efficient approach). The next page provides a listing of the Portolan issues and their dates of publication. PORTOLAN ISSUE NUMBERS AND PUBLICATIONS DATES Issue # Publication Date Issue # Publication Date 100 Winter 2017 050 Spring 2001 099 Fall 2017 049 Winter 2000-2001 098 Spring 2017 048 Fall 2000 097 Winter 2016 047 Srping 2000 096 Fall 2016 046 Winter 1999-2000 095 Spring 2016 045 Fall 1999 094 Winter 2015 044 Spring -

Postmaster and the Merton Record 2019

Postmaster & The Merton Record 2019 Merton College Oxford OX1 4JD Telephone +44 (0)1865 276310 www.merton.ox.ac.uk Contents College News Edited by Timothy Foot (2011), Claire Spence-Parsons, Dr Duncan From the Acting Warden......................................................................4 Barker and Philippa Logan. JCR News .................................................................................................6 Front cover image MCR News ...............................................................................................8 St Alban’s Quad from the JCR, during the Merton Merton Sport ........................................................................................10 Society Garden Party 2019. Photograph by John Cairns. Hockey, Rugby, Tennis, Men’s Rowing, Women’s Rowing, Athletics, Cricket, Sports Overview, Blues & Haigh Awards Additional images (unless credited) 4: Ian Wallman Clubs & Societies ................................................................................22 8, 33: Valerian Chen (2016) Halsbury Society, History Society, Roger Bacon Society, 10, 13, 36, 37, 40, 86, 95, 116: John Cairns (www. Neave Society, Christian Union, Bodley Club, Mathematics Society, johncairns.co.uk) Tinbergen Society 12: Callum Schafer (Mansfield, 2017) 14, 15: Maria Salaru (St Antony’s, 2011) Interdisciplinary Groups ....................................................................32 16, 22, 23, 24, 80: Joseph Rhee (2018) Ockham Lectures, History of the Book Group 28, 32, 99, 103, 104, 108, 109: Timothy Foot -

SIS Bulletin Issue 68

Scientific Inst~ u: nent SOciety • ~ ~': ~z ~ ........ ....... ~ :~,,, _~ , ......~ ,~ ., .. ~. "i I, ~'~..~ i;.)~ i!~ ~' • Bulletin March No. 68 2001 Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society IssN 0956-8271 For Table of Contents, see back cover President Gerard Turner Vice-President Howard Dawes Honorary Committee Stuart Talbot, Chairman Gloria Clifton, SecretaW John Didcock, Treasurer WiUem Hackmann, Editor Sunon Chetfetz Alexander Crum-Ewmg Peter de Clercq Tom l~mb Svh'ia Sunmra L~ba Taub Membership and Administrative Matters The Executive Officer (Wg Cdr Geoffrey Bennett) 31 HJ~h Sweet Stanford m the Vale Farmgdon Tel: 01367 710223 Oxon SNr7 8LH Fax: 01367 718963 e-mail: [email protected] See outside back cover for infvrmation on membership Editorial Matters Dr. Willem D. Hackmann Museum of the History of Science Old Ashmolean Building Tel: 01865 277282 (office) Broad Street Fax: 01865 277288 Oxford OXI 3AZ Tel: 01608 811110 (home) e-mail: willemhackmann@m~.ox,ac.uk " Society's Website http://ww~,.sis.org.uk Advertising .See 'Summary of Advertising Services' panel elsewhere in this Bulletin. Further enquiries to the Executive Officer. Typesetting and Printing IJthoflow Ltd 26-36 Wharfdale Road Tel: 020 7833 2344 King's Cross Fax: 020 7833 8150 London N1 9RY Price: £6 per issue, including back numbers where available. (Enquiries to the Executive Officer) The Scientific Instrument Society is Registered Charily No. 326733 :~ The Scientific Instrument Society 2001 i; Editorial Spring is in the Air - Somewhere maxnum opus on Elizabethan Lnstruments. Getting the March Bulletin ready always Object' brings with it a special excitement as it This issue's 'Mystery has elicited a coincides with nature awakening from its great deal of interest,and has been correctly winter slumber; there is a sense of renewal, identified as what the German's call a for measunng the of new plausibilities. -

Scientific Instrument Curators in Britain: Building a Discipline with Material Culture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Museums Scotland Research Repository Alberti, S J M M (2018) Scientific instrument curators in Britain: building a discipline with material culture. Journal of the History of Collections (fhy027). ISSN 1477-8564 https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhy027 Deposited on: 09 December 2019 NMS Repository – Research publications by staff of the National Museums Scotland http://repository.nms.ac.uk/ Journal of the History of Collections vol. 31 no. 3 (2019) pp. 519–530 Scientific instrument curators in Britain Building a discipline with material culture Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jhc/article-abstract/31/3/519/5077066 by National Museums Scotland user on 09 December 2019 Samuel J.M.M. Alberti From the mid-1960s a new breed of scientific instrument curators emerged in the United Kingdom. This small community of practice developed in parallel to but distinctly from the expanding generation of university historians of science and other cognate museum sub-professions. Presenting the trajectories, experiences and practices of personnel in British scientific instrument collections, especially the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh, this article explores how networks of interest around collections shaped the museum sector in later twentieth-century Britain. With particular objects – especially eighteenth-century instruments – the ‘brass brigade’ built a discipline. On 3 September 1968, sixty curators and other The museum professionals present at the ‘Aspects’ historians gathered at the Royal Scottish Museum meeting formed part of a distinct cohort emerging at in Edinburgh to discuss ‘Aspects of Eighteenth- this time. -

Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England

The Ingenious Mr Dummer: Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England Celina Fox In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Royal Navy constituted by far the greatest enterprise in the country. Naval operations in and around the royal dockyards dwarfed civilian industries on account of the capital investment required, running costs incurred and logistical problems encountered. Like most state services, the Navy was not famed as a model of efficiency and innovation. Its day-to-day running was in the hands of the Navy Board, while a small Admiralty Board secretariat dealt with discipline and strategy. The Navy Board was responsible for the industrial organization of the Navy including the six royal dockyards; the design, construction and repair of ships; and the supply of naval stores. In practice its systems more or less worked, although they were heavily dependent on personal relationships and there were endless opportunities for confusion, delay and corruption. The Surveyor of the Navy, invariably a former shipwright and supposedly responsible for the construction and maintenance of all the ships and dockyards, should have acted as a coordinator but rarely did so. The labour force worked mainly on day rates and so had no incentive to be efficient, although a certain esprit de corps could be relied upon in emergencies.1 It was long assumed that an English shipwright of the period learnt his art of building and repairing ships primarily through practical training and experience gained on an apprenticeship, in contrast to French naval architects whose education was grounded on science, above all, mathematics. -

A Classified Bibliography on the History of Scientific Instruments by G.L'e

A Classified Bibliography on the History of Scientific Instruments by G.L'E. Turner and D.J. Bryden Originally published in 1997, this Classified Bibliography is "Based on the SIC Annual Bibliographies of books, pamphlets, catalogues and articles on studies of historic scientific instruments, compiled by G.L'E. Turner, 1983 to 1995, and issued by the Scientific Instrument Commission. Classified and edited by D.J. Bryden" (text from the inside cover page of the original printed document). Dates for items in this bibliography range from 1979 to 1996. The following "Acknowledgments" text is from page iv of the original printed document: The compiler thanks the many colleagues throughout the world who over the years have drawn his attention to publications for inclusion in the Annual Bibliography. The editor thanks Miss Veronica Thomson for capturing on disc the first 6 bibliographies. G.L'E. Turner, Oxford D.J. Bryden, Edinburgh April 1997 ASTROLABE ACKERMANN, S., ‘Mutabor: Die Umarbeitung eines mittelalterlichen Astrolabs im 17. Jahrhundert’, in: von GOTSTEDTER, A. (ed), Ad Radices: Festband zum fünfzigjährrigen Bestehen des Instituts für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften der Johann Wolfgang Goethe- Universtät Frankfurt am Main (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1994), 193-209. ARCHINARD, M., Astrolabe (Geneva: Musée d'histoire des Sciences de Genève, 1983). 40pp. BORST, A., Astrolab und Klosterreform an der Jahrtausendwende (Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitatsverlag, 1989) (Sitzungsberichte der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften Philosophisch-historische Klasse). 134pp. BROUGHTON, P., ‘The Christian Island "Astrolabe" ’, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 80, no.3 (1986), 142-53. DEKKER, E., ‘An Unrecorded Medieval Astrolabe Quadrant c.1300’, Annals of Science, 52 (1995), 1-47. -

The Greenwich Clock at Towneley by Tony Kitto

The Greenwich Clock at Towneley by Tony Kitto Towneley Hall Art Gallery and Museums 2007 Copyright Burnley Borough Council Reading the time from the Greenwich Clock The hour hand goes round the dial once every twelve hours in the usual way but the minute and second hands take twice as long as is normal. It takes 2 hours for the minute hand to go round. At the top of the dial, starting at 12 o'clock, there are 60 divisions of one minute down to 6 o'clock and another 60 divisions back to 12 o'clock. The minutes are difficult to read because the minute hand shares the same dial as the hour hand. In comparison, it is relatively easy to read the second hand. The second hand goes round its own dial with 120 divisions, marked out in 10 second periods, once every 2 minutes. We expect a minute hand to go round the dial once an hour. Most people estimate the time from the angle of the minute hand but that is misleading when looking at this clock. 2:00 ? 2:15 ? 3:30 ? 3:45? 4:00? yes no, its 2:30 no, its 3:00 no, its 3:30 yes The Greenwich Clock at Towneley The Greenwich Clock in the entrance hall at Towneley is a reconstruction of one of a pair of clocks presented to the Royal Observatory at Greenwich by Sir Jonas Moore in 1676. It was made in 1999 by Alan Smith of Worsley, Greater Manchester, to show how the original clocks worked. -

Mathematical Instruments Commonly Used Among the Ottomans

Advances in Historical Studies, 2019, 8, 36-57 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ahs ISSN Online: 2327-0446 ISSN Print: 2327-0438 Mathematical Instruments Commonly Used among the Ottomans Irem Aslan Seyhan Department of Philosophy, Bartın University, Bartın, Turkey How to cite this paper: Seyhan, I. A. Abstract (2019). Mathematical Instruments Com- monly Used among the Ottomans. Ad- At the end of 17th century and during 18th century, after devastating Russian vances in Historical Studies, 8, 36-57. wars the Ottomans realized that they fell behind of the war technology of the https://doi.org/10.4236/ahs.2019.81003 Western militaries. In order to catch up with their Western rivals, they de- cided that they had to reform their education systems. For that they sent sev- Received: January 24, 2019 Accepted: March 5, 2019 eral students to abroad for education and started to translate Western books. Published: March 8, 2019 They established Western style military academies of engineering. They also invited foreign teachers in order to give education in these institutes and they Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and consulted them while there were preparing the curriculum. For all these, Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative during the modernization period, the reform (nizâm-ı cedid) planers mod- Commons Attribution International elled mainly France, especially for teaching the applied disciplines. Since their License (CC BY 4.0). main aim was to grasp the technology of the West, their interest focused on http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ the applied part of sciences and mathematics. -

Cromwelliana

Cromwelliana The Journal of The Cromwell Association 2017 The Cromwell Association President: Professor PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS Vice Presidents: PAT BARNES Rt Hon FRANK DOBSON, PC Rt Hon STEPHEN DORRELL, PC Dr PATRICK LITTLE, PhD, FRHistS Professor JOHN MORRILL, DPhil, FBA, FRHistS Rt Hon the LORD NASEBY, PC Dr STEPHEN K. ROBERTS, PhD, FSA, FRHistS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA Chairman: JOHN GOLDSMITH Honorary Secretary: JOHN NEWLAND Honorary Treasurer: GEOFFREY BUSH Membership Officer PAUL ROBBINS The Cromwell Association was formed in 1937 and is a registered charity (reg no. 1132954). The purpose of the Association is to advance the education of the public in both the life and legacy of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), politician, soldier and statesman, and the wider history of the seventeenth century. The Association seeks to progress its aims in the following ways: campaigns for the preservation and conservation of buildings and sites relevant to Cromwell commissions, on behalf of the Association, or in collaboration with others, plaques, panels and monuments at sites associated with Cromwell supports the Cromwell Museum and the Cromwell Collection in Huntingdon provides, within the competence of the Association, advice to the media on all matters relating to the period encourages interest in the period in all phases of formal education by the publication of reading lists, information and teachers’ guidance publishes news and information about the period, including an annual journal and regular newsletters organises an annual service, day schools, conferences, lectures, exhibitions and other educational events provides a web-based resource for researchers in the period including school students, genealogists and interested parties offers, from time to time grants, awards and prizes to individuals and organisations working towards the objectives stated above. -

United States National Museum

? Lat. Capitol, .58:.^,5, N. lEBBf/^ Lonl 0: 0. l/BEiF) ]E/iEP^ cnLVv ,Ei^tS^ "tnnB EEC^ ^^ferjtiBt^ GEOKGEnnnnDco\\T 3Er^t> ^«r;j]p prac^ iSlilEEBiR up 13 0BSERT^\TI0]VS explanatory of the 1. lHE-f>csitto,isJ,rthc ili/jrrent Jiflifirc.,, m„7/h- //i several S^uairs cr. 4rca., ofdi^eni shxfts. as tha, an htd ^ rlvun,. utrejirst detcniuned vn t/„ „„^t ,uh„„tar^,,,s ,;n;„u/, ^ m„mar.dn,r^ ,Ar „„^r r.vh„st,rfirasfjrrfs, and du letter s,ucrphH^ >fsuc/, nuf„-r,rn,n,Ts. a., nt/.rr ase or ,.r„a,„n,l ,„a>, /.nra,ln^- 11. L.INi:S or. irrnues rfdirrct ronn,n„ar„tw„ /.mr Orrn dn, b> co„nrrr thr .,.,,„rnte „ud .„os, d,.,fan, oh,rrt. ,n,/, d,e pnnrn, and y,„.nr //„„,/, ,/,, ,,/,./. a rrri^, rr,,,,,.;:.,„J,j f,^,,i, ^^'''f'r'; /'^s /rrn^uf fo d,r/,a^^,,>; ,fr/u^., f„,,/,,,,:_ y„,^,„^.. ,„^^ moMJarcrohh r^,r,o<d /,:,y.n.,^rf and rrarr,an,rr. M.JfojtrB and Aon,/, l.nrs .nUrseCrd In, rtUrs n..,„.a, due Eas, a„d fn.r., hare f.rn so co,nhu,ed a, A, ».rr, a, crrUa,, .pj„f,..n„s ,,,7/ ,(,,.„ ^nnyral. i.r„ar... ,,o a., to on //>r A).„er., f,r,„ '//rst drf'r,„u,rdr ,/, SmmrfS cr. /rras. Scale of Poles, 6i<c -Prirs. f)' Iiirbrs. ''^ idCrrfk S .-^^pf the CITY o£^ ( of Coliunbia, ) ) r. / r "^n tKe TprrifoF>' "^^^^ ceded hv the States of ^^-^ Virgi:n^ia and Maryla:nd I '-'-ft a , i&s Cfimti0 5^tat<8 OF x!i\\\ix\tiK\ aiK^ ,7^I'll l/icin endNi.ilirfl <i.> llie Seat <?/ then tir/e/- r/if '//^///' md6cc.