Maria Robinson-Cseke Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aird Gallery Robert Houle

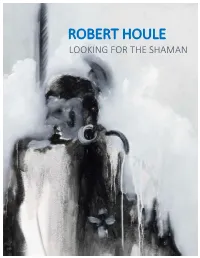

ROBERT HOULE LOOKING FOR THE SHAMAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Carla Garnet ARTIST STATEMENT by Robert Houle ROBERT HOULE SELECTED WORKS A MOVEMENT TOWARDS SHAMAN by Elwood Jimmy INSTALL IMAGES PARTICIPANT BIOS LIST OF WORKS ABOUT THE JOHN B. AIRD GALLERY ROBERT HOULE CURRICULUM VITAE (LONG) PAMPHLET DESIGN BY ERIN STORUS INTRODUCTION BY CARLA GARNET The John B. Aird Gallery will present a reflects the artist's search for the shaman solo survey show of Robert Houle's within. The works included are united by artwork, titled Looking for the Shaman, their eXploration of the power of from June 12 to July 6, 2018. dreaming, a process by which the dreamer becomes familiar with their own Now in his seventh decade, Robert Houle symbolic unconscious terrain. Through is a seminal Canadian artist whose work these works, Houle explores the role that engages deeply with contemporary the shaman plays as healer and discourse, using strategies of interpreter of the spirit world. deconstruction and involving with the politics of recognition and disappearance The narrative of the Looking for the as a form of reframing. As a member of Shaman installation hinges not only upon Saulteaux First Nation, Houle has been an a lifetime of traversing a physical important champion for retaining and geography of streams, rivers, and lakes defining First Nations identity in Canada, that circumnavigate Canada’s northern with work exploring the role his language, coniferous and birch forests, marked by culture, and history play in defining his long, harsh winters and short, mosquito- response to cultural and institutional infested summers, but also upon histories. -

Liss Platt 151 Ray Street North • Hamilton, Ontario L8R 2Y3 905.525.4363 (Phone) • 905.966.6352 (Cell) [email protected] • Lissplatt.Ca

Liss Platt 151 Ray Street North • Hamilton, Ontario L8R 2Y3 905.525.4363 (phone) • 905.966.6352 (cell) [email protected] • lissplatt.ca EDUCATION 1992-93 Whitney Independent Study Program, Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, NY. 1992 Master of Fine Arts, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA. 1988 Bachelor of Fine Arts, The University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT. 1986 The Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, Nova Scotia; Exchange Program. SOLO and TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS, SCREENINGS, PERFORMANCES 2018 b Contemporary, dis/order, Hamilton, ON (photos) 2017 McMaster Museum of Art, Liss Platt - A Constant Decade, Hamilton, ON (photos and videos) Hamilton Artist’s Inc, Domestic Brew: 99 Bottles of Beer on the Wall, Hamilton, ON (Shake-n- Make - sculptural installation and billboard photograph) The Cotton Factory, Hand of Craft, Hamilton, ON (Shake-n-Make – installation) 2015 AXENÉO7, puck painting performance, Gatineau, QC (performance – making a puck painting) Chester Street News, what’s cookin’, Toronto ON (Shake-n-Make collective – crafts/objects) McMaster Museum of Art, Dark Horse Candidate, Hamilton, ON (screening of feature documentary) 2014 MKG127, dis/order, Toronto, ON (photographs) Struts Gallery/Faucet New Media, Call of the Running Tide, Sackville, NB (performance and installation) (2-person show with David Hoffos/Mary Anne McTrowe) 2012 Rodman Hall Art Centre, You Can’t Get There From Here, St. Catherines, ON (video projection, photographs, postcard installation) MKG127, Constant, Toronto, ON (photographs) -

Geoffrey Farmer’S Canadian Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale by Alex Greenberger

Details Announced for Geoffrey Farmer’s Canadian Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale BY Alex Greenberger For his Canadian Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, Geof- frey Farmer will once again return to his interest in the re- lationship between people and their pictures. In an installation titled A way out of the mirror, he will draw inspiration from a 1955 group of photographs showing a lumber truck that collided with a moving train. Farmer has a personal con- nection to the photographs: his grandfather, who would himself later die in an accident, was present when they were taken. The Vancouver-based artist never knew that, howev- er, until his sister emailed him the images last year. The installation takes its name from an Allen Ginsberg poem—Farmer recalls hold- ing a copy of Howl, Gins- berg’s 1955 epic poem, when Untitled (Collision), 1955. ARCHIVES OF THE ARTIST he opened his sister’s email. Farmer also remembers listen- ing to Ginsberg sing when, as a student at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1991, he first learned about the Venice Biennale. “In his Venice project, Geoffrey once again finds a world enclosed inside an image and an image giving rise to a world,” Kitty Scott, a curator of modern and contemporary art at the Art Gallery of Ontario and the organizer of the pavilion, said in a state- ment. (Scott worked with Josée Drouin-Brisebois, a curator of contemporary art at the National Gallery of Canada and the pa- vilion’s project director.) “Personal memory and familial history flow into a broader stream of reflections on inheritance, trauma, and desire. -

Haunted Canada: the Ninth Annual Trent-Carleton 2013 Graduate Conference in Canadian Studies

Haunted Canada: The Ninth Annual Trent-Carleton 2013 Graduate Conference in Canadian Studies. Held at Carleton University, March 15-16 “Haunted Landscapes: David Hoffos’ Scenes From the House Dream,” presented by Sarah Eastman. Scenes From the House Dream is an immersive video installation by Lethbridge, Alberta artist David Hoffos. It features a darkened gallery, and miniature dioramas which are viewed through windows in the gallery walls (Fig. 1). The installation, completed in 2009, was the culmination of five years of work and is a continuation of Hoffos’ previous artistic experimentation with video, scale models, and illusion. The title refers to the inspiration behind the work; in an interview with Robert Enright, Hoffos notes that the “house dream” is a common, recurring dream about a house. He describes this dream house as a familiar space, which holds surprises because it is continuously changing and expanding.1 Much of the previous scholarship on Scenes From the House Dream takes the dream as its starting point. The four essays published in the exhibition catalogue David Hoffos: Scenes From the House Dream focus on themes of suburbia, the home, the uncanny, and the exhibition as a dream space.2 The role of domestic space has also been studied; in his article “Home Thoughts” Bruce Baugh argues that Hoffos’ work depicts the home as a kind of failed utopia.3 He writes: By making a miniature model of the stereotypical ideal of ‘home’ (modern,middle class, suburban, North American, two-car garage) and simply dimming the lights, Hoffos defamiliarizes the familiar, and introduces the uncertainty of not quite knowing where one is: of being not-at-home in being at ‘home.’4 1 Robert Enright, “Overwhelmer: The Art of David Hoffos,” Border Crossings 25 no. -

The Gallery Guide | November 2008 – January 2009

C A G L A EN L D L A ER R Y O I F N O D P EX E - N P IN G G 8 S 2 - P G 8 6 THE GALLERY GUIDE ALBERT A I BRITISH COLUMBI A I OREGO N I WASHINGTON November/December/January 2008/09 www.preview-art.com Serving the visual arts community Celebrating since 1986 22 years www.preview-art.com 6 PREVIEW previews Vol. 22 No. 5 ALBERTA 10 David Hoffos 8 CalgarY 10 Southern Alberta Art Gallery 14 Edmonton Esplanade Art Gallery 15 Lethbridge 16 Medicine Hat, Red Deer 12 John Hartman: Cities BRITISH COLUMBIA Paul Kuhn Gallery 16 BurnabY 17 Campbell RiVer, Castlegar 16 Wanda Lock: Stacks and Piles 18 ChilliWack, Coquitlam Kelowna Art Gallery 22 CourtenaY 23 Delta, Denman Island, Duncan, 18 Juliette and Friends Fort LangleY, Gabriola Island Presentation House Gallery 25 Galiano Island, Grand Forks , Kamloops 22 Marie Watt 26 Kaslo, KeloWna Greg Kucera Gallery 27 Lions BaY, Maple Ridge, Nanaimo 18 28 Nanoose BaY, Nelson, 36 26 Cole Morgan NeW Westminster Gallery Jones 29 North Vancou Ver 30 OsoYoos, Penticton 28 Hiro Yamagata: TRANSIENT 31 Port MoodY Hodnett Fine Art 32 Prince George, Prince Rupert, Quadra Island, Qualicum Beach, 34 Adaptation: Ben-Ner, Herrera, Sullivan, Richmond and Sussman & The Rufus Corporation 33 Salmon Arm, Salt Spring Island, Henry Art Gallery SidneY 34 SidneY-North Saanich, SilVer 36 Alan Wood: Dreams and Memories Star Mountain, Sooke Winsor Gallery 35 Squamish, Summerland, Sunshine Coast 42 Edward Burtynsky: Uneasy Beauty 36 SurreY 70 Surrey Art Gallery 37 TsaWWassen, VancouVer 8 59 Vernon, Victoria 7 48 Chris Langstroth: New -

Artist Biographies

Artist Biographies Kim Adams (BFA and MFA, University of Victoria, BC) lives and works in Grand Valley and Toronto, Ontario. Recent solo exhibitions include the Harbourfront Centre, Toronto, in honor of the 75th Anniversary of the Banff Centre; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; The Power Plant, Toronto; Art Gallery of Hamilton, ON; Ontario College of Art and Design, Toronto; Musée d'art contemPorain de Montréal; and Centraal Museum, Utrecht, Netherlands. GrouP exhibitions include Wandering Positions/Here We Go Again, Museum of ContemPorary Art, Mexico City; Adaptations, APexart, New York, and Kunsthalle Friedericanum, Kassel, Germany; Insiders, Centre d’architecture and CAPC Musée d’art contemPorain, Bordeaux; The Big Gift, Glenbow Museum, Calgary; Cabin, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; El Geni de Les Coses, Office for Artistic Diffusion (ODA), Barcelona; the 2002 Sydney Biennale; and Model World, The Aldrich ContemPorary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT. Adams’s work is included in numerous Private collections and Public collections, such as the Musée d'art contemPorain de Montréal; National Gallery of Canada; Centraal Museum, Utrecht; Collection Publique d’art contemPorain du Conseil général de la Seine-Saint-Denis, Paris; Vancouver Art Gallery; and the Art Gallery of Ontario. Gisele Amantea (BFA, University of Calgary; MFA, University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, WA) lives and works in Montreal, Quebec. Amantea has had solo exhibitions at the Musée d’art de Joliette, QC; Seagull Arts and Media Resource Centre, Kolkata, India; the Walter PhilliPs Gallery, Banff; the Centre d’art contemPorain de Basse-Normandie, Hérouville St. Clair, France; Oboro Artists’ Centre, Montreal; and YYZ Artists’ Outlet, Toronto. In APril 2007, The King v. -

Faculty of Media, Art, and Performance 2016 01-06 Teaching History

Ruth Chambers Professor [email protected], (306) 585 5575, Education and Professional Development Master of Fine Art, University of Regina, Saskatchewan 1994 University of Guelph, Art History undergraduate courses 1995 University of Wisconsin, Madison, Special Student, Graduate Studies 1985 Sun Valley Center for the Arts and Humanities, Sun Valley, (U of Idaho) Ceramics 1984/83 AOCA, Ontario College of Art, (OCAD University) Toronto, ON, Honours 1983 Employment History Professor, Department of Visual Art, University of Regina 2009- present Acting Associate Dean, Undergrad, Faculty of Media, Art, and Performance 2016 01-06 Teaching History Introduction to Ceramics: ART 260 Intermediate Ceramics: ART 360 Thematic Intermediate Ceramics Courses: ART 361, ART 362, ART 363, ART 364 Undergraduate Directed Reading Courses: ART 390, ART 490 Advanced Ceramics Courses: ART 460, ART 461, ART 462, ART 463, ART 464 Open Studio Courses: ART 416-419 Group Studio Courses: ART 410- 412 Graduate directed reading Courses: ART 860, ART 890, ART 902 Graduate Group Studio: ART 801-803 Student Supervision Name Position Dates of supervision Brenda Watt MFA September 2020 to present Brenda Danbrook MFA Co-supervision Sept 2016 -2018 Olivia Rosema MFA Co-supervision Sept 2014 - 2017 Denise Smith MFA Co-supervision Sept 2014 - 2017 Jody Greenman-Barber MFA Sept 2013- 2015 April Fairbrother MFA graduated 2012 Zane Wilcox MFA graduated 2011 Alex Sparkes MFA Sept 2011 – Sept 2012 Troy Coulterman MFA Co-supervision grad 2012 Michelle Markatos Post Bacc Certificate