2. the Avengers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captain America

TIMELY COMICS MARCH 1941 CAPTAIN AMERICA Captain America is a fictional character that appears in comic books published by Marvel Comics. Early Years and WWII Steve Rogers was a scrawny fine arts student specializing in industrialization in the 1940's before America entered World War II. He attempted to enlist in the army only to be turned away due to his poor constitution. A U.S. officer offered Rogers an alternative way to serve his country by being a test subject in project, Operation: Rebirth, a top secret defense research project designed to create physically superior soldiers. Rogers accepted and after a rigorous physical and combat training and selection process was selected as the first test subject. He was given injections and oral ingestion of the formula dubbed the "Super Soldier Serum" developed by the scientist Dr. Abraham Erskine. Rogers was then exposed to a controlled burst of "Vita-Rays" that activated and stabilized the chemicals in The Golden Age of Comics his system. The process successfully altered his physiology from its frail state The Golden Age of Comic Books among them Superman, Batman, to the maximum of human efficiency, was a period in the history of Captain America, and Wonder including greatly enhanced musculature American comic books, generally Woman. and reflexes. After the assassination of Dr. thought of as lasting from the late Erskine. Roger was re-imagined as a The period saw the arrival of the 1930s until the late 1940s. During superhero who served both as a counter- comic book as a mainstream art intelligence agent and a propaganda this time, modern comic books form, and the defining of the symbol to counter Nazi Germany's head of were first published and enjoyed a medium's artistic vocabulary and terrorist operations, the Red Skull. -

Sloane Drayson Knigge Comic Inventory (Without

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Number Donor Box # 1,000,000 DC One Million 80-Page Giant DC NA NA 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 A Moment of Silence Marvel Bill Jemas Mark Bagley 2002 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alex Ross Millennium Edition Wizard Various Various 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Open Space Marvel Comics Lawrence Watt-Evans Alex Ross 1999 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alf Marvel Comics Michael Gallagher Dave Manak 1990 33 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 2 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 3 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 4 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 5 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 6 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Aphrodite IX Top Cow Productions David Wohl and Dave Finch Dave Finch 2000 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 600 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 601 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 602 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 603 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 -

Jun 18 Customer Order Form

#369 | JUN19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JUN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Jun19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:08:57 PM June19 Humanoids Ad.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:15:02 PM SPAWN #300 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN/SUPERMAN #1 DC COMICS COFFIN BOUND #1 GLOW VERSUS IMAGE COMICS THE STAR PRIMAS TP IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN VS. RA’S AL GHUL #1 DC COMICS BERSERKER UNBOUND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS THE DEATH-DEFYING DEVIL #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS #1000 MARVEL COMICS HELLBOY AND THE B.P.R.D.: SATURN RETURNS #1 ONCE & FUTURE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS Jun19 Gem Page.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:24:56 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Bad Reception #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Flash: Crossover Crisis Book 1: Green Arrow’s Perfect Shot HC l AMULET BOOKS Archie: The Married Life 10 Years Later #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Warrior Nun: Dora #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars: Rey and Pals HC l CHRONICLE BOOKS 1 Lady Death Masterpieces: The Art of Lady Death HC l COFFIN COMICS 1 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons l DISNEY EDITIONS Moomin: The Lars Jansson Edition Deluxe Slipcase l DRAWN & QUARTERLY The Poe Clan Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Cycle of the Werewolf SC l GALLERY 13 Ranx HC l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Superman and Wonder Woman With Collectibles HC l HERO COLLECTOR Omni #1 l HUMANOIDS The Black Mage GN l ONI PRESS The Rot Volume 1 TP l SOURCE POINT PRESS Snowpiercer Hc Vol 04 Extinction l TITAN COMICS Lenore #1 l TITAN COMICS Disney’s The Lion King: The Official Movie Special l TITAN COMICS The Art and Making of The Expance HC l TITAN BOOKS Doctor Mirage #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT The Mall #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 2 World’s End Harem: Fantasia Volume 1 GN l GHOST SHIP My Hero Academia Smash! Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Kingdom Hearts: Re:Coded SC l YEN ON Overlord a la Carte Volume 1 GN l YEN PRESS Arifureta: Commonplace to the World’s Strongest Zero Vol. -

Everybody Loves a Muscle Boi”: Homos, Heroes, and Foes in Post-9/11 Spoofs of the 300 Spartans

1 “Everybody Loves a Muscle Boi”: Homos, Heroes, and Foes in Post-9/11 Spoofs of the 300 Spartans Ralph J. Poole “It’s Greek to whom?” In 2007-2008, a significant accumulation of cinematic and other visual media took up a celebrated episode of Greek antiquity recounting in different genres and styles the rise of the Spartans against the Persians. Amongst them are the documentary The Last Stand of the 300 (2007, David Padrusch), the film 300 (2007, Zack Snyder), the video game 300: March to Glory (2007, Collision Studios), the short film United 300 (2007, Andy Signore), and the comedy Meet the Spartans (2008, Jason Friedberg/Aaron Seltzer). Why is the legend of the 300 Spartans so attractive for contemporary American cinema? A possible, if surprising account for the interest in this ancient theme stems from an economic perspective. Written at the dawn of the worldwide financial crisis, the fight of the 300 Spartans has served as point of reference for the serious loss of confidence in the banking system, but also in national politics in general. William Streeter of the ABA Banking Journal succinctly wonders about what robs bankers’ precious resting hours: What a fragile thing confidence is. Events of the past six months have seen it coalesce and evaporate several times. […] This is what keeps central bankers awake at night. But then that is their primary reason for being, because the workings of economies and, indeed, governments, hinge upon trust and confidence. […] With any group, whether it be 300 Spartans holding off a million Persians at Thermopylae or a group of central bankers trying to keep a global financial community from bolting, trust is a matter of individual decisions. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

Ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2011 Remas(k)ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film Carolyn P. Fisher College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Fisher, Carolyn P., "Remas(k)ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 402. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/402 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Remas(k)ulating the American Man: Fear and Masculinity in the Post-9/11 American Superhero Film by Carolyn Fisher A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from The College of William and Mary Accepted for _________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ______________________________________ Dr. Colleen Kennedy, Director ______________________________________ Dr. Frederick Corney ______________________________________ Dr. Arthur Knight Williamsburg, VA April 15, 2011 Fisher 1 Introduction Superheroes have served as sites for the reflection and shaping of American ideals and fears since they first appeared in comic book form in the 1930s. As popular icons which are meant to engage the American imagination and fulfill (however unrealistically) real American desires, they are able to inhabit an idealized and fantastical space in which these desires can be achieved and American enemies can be conquered. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

2015 Upper Deck Marvel Avengers Age of Ultron Final Checklist

2015 Upper Deck Marvel Avengers Age of Ultron Final Checklist Card First Name Last Name Set Name Notes 1 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 2 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 3 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 4 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 5 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 6 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 7 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 8 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 9 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 10 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 11 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 12 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 13 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 14 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 15 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 16 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 17 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 18 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 19 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 20 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 21 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 22 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 23 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 24 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 25 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 26 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 27 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 28 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 29 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 30 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 31 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 32 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 33 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 34 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 35 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 36 Age of Ultron Avengers Age of Ultron 37 Age of Ultron Avengers Age -

This Session Will Be Begin Closing at 6PM on 5/19/20, So Be Sure to Get Those Bids in Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook & Twitter @Back2past for Updates

5/19 Bronze to Modern Comic Books, Board Games, & Toys 5/19/2021 This session will be begin closing at 6PM on 5/19/20, so be sure to get those bids in via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook & Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Policies 1 13 Uncanny X-Men #350/Gambit Holofoil Cover 1 Holofoil cover art by Joe Madureira. NM condition. 2 Amazing Spider-Man #606/Black Cat Cover 1 Cover art by J. Scott Campbell featuring The Black Cat. NM 14 The Mighty Avengers Near Run of (34) Comics 1 condition. First Secret Warriors. Lot includes issues #1-23, 25-33, and 35-36. NM condition. 3 Daredevil/Black Widow Figure Lot 1 Marvel Select. New in packages. Package have minor to moderate 15 Comic Book Superhero Trading Cards 1 shelf wear. Various series. Singles, promos, and chase cards. You get all pictured. 4 X-Men Origins One-Shot Lot of (4) 1 Gambit, Colossus, Emma Frost, and Sabretooth. NM condition. 16 Uncanny X-Men #283/Key 1st Bishop 1 First full appearance of Bishop, a time-traveling mutant who can 5 Guardians of The Galaxy #1-2/Key 1 New roster and origin of the Guardians of the Galaxy: Star-Lord, absorb and redistribute energy. NM condition. Gamora, Drax, Rocket Raccoon, Adam Warlock, Quasar and 17 Crimson Dawn #1-4 (X-Men) 1 Groot. -

Kirby: the Wonderthe Wonderyears Years Lee & Kirby: the Wonder Years (A.K.A

Kirby: The WonderThe WonderYears Years Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years (a.k.a. Jack Kirby Collector #58) Written by Mark Alexander (1955-2011) Edited, designed, and proofread by John Morrow, publisher Softcover ISBN: 978-1-60549-038-0 First Printing • December 2011 • Printed in the USA The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 18, No. 58, Winter 2011 (hey, it’s Dec. 3 as I type this!). Published quarterly by and ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Four-issue subscriptions: $50 US, $65 Canada, $72 elsewhere. Editorial package ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All artwork is ©2011 Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. Editorial matter ©2011 the respective authors. ISSN 1932-6912 Visit us on the web at: www.twomorrows.com • e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the publisher. (above and title page) Kirby pencils from What If? #11 (Oct. 1978). (opposite) Original Kirby collage for Fantastic Four #51, page 14. Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to my Aunt June for buying my first Marvel comic, and for everything else. Next, big thanks to my son Nicholas for endless research. From the age of three, the kid had the good taste to request the Marvel Masterworks for bedtime stories over Mother Goose. He still holds the record as the youngest contributor to The Jack Kirby Collector (see issue #21). Shout-out to my partners in rock ’n’ roll, the incomparable Hitmen—the best band and best pals I’ve ever had. -

CUSTOMER ORDER FORM (Net)

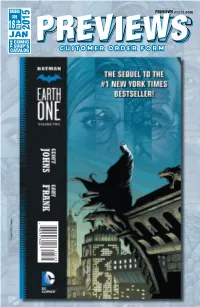

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 JAN 2015 JAN COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jan15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:14:17 PM Available only from your local comic shop! STAR WARS: “THE FORCE POSTER” BLACK T-SHIRT Preorder now! BIG HERO 6: GUARDIANS OF THE DC HEROES: BATMAN “BAYMAX BEFORE GALAXY: “HANG ON, 75TH ANNIVERSARY & AFTER” LIGHT ROCKET & GROOT!” SYMBOL PX BLACK BLUE T-SHIRT T-SHIRT T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now! 01 Jan15 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:06:36 PM FRANKENSTEIN CHRONONAUTS #1 UNDERGROUND #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: EARTH ONE VOLUME 2 HC DC COMICS PASTAWAYS #1 DESCENDER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS IMAGE COMICS JEM AND THE HOLOGRAMS #1 IDW PUBLISHING CONVERGENCE #0 ALL-NEW DC COMICS HAWKEYE #1 MARVEL COMICS Jan15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 2:59:43 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Fox #1 l ARCHIE COMICS God Is Dead Volume 4 TP (MR) l AVATAR PRESS The Con Job #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Bill & Ted’s Most Triumphant Return #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 3 #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS/ARCHAIA PRESS Project Superpowers: Blackcross #1 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Angry Youth Comix HC (MR) l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 Hellbreak #1 (MR) l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: The Ninth Doctor #1 l TITAN COMICS Penguins of Madagascar Volume 1 TP l TITAN COMICS 1 Nemo: River of Ghosts HC (MR) l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Ninjak #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT BOOKS The Art of John Avon: Journeys To Somewhere Else HC l ART BOOKS Marvel Avengers: Ultimate Character Guide Updated & Expanded l COMICS DC Super Heroes: My First Book Of Girl Power Board Book l COMICS MAGAZINES Marvel Chess Collection Special #3: Star-Lord & Thanos l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #1 l COMICS Alter Ego #132 l COMICS Back Issue #80 l COMICS 2 The Walking Dead Magazine #12 (MR) l MOVIE/TV TRADING CARDS Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. -

Trends in Gender Portrayal in the Marvel Cinematic Universe Avengers Series: a Conventional Content Analysis

Volume 10 Issue 1 (2021) Trends in Gender Portrayal in the Marvel Cinematic Universe Avengers Series: A Conventional Content Analysis Haley Morales1 and Daniel Olivo1 1Bergen County Technical High School, Teterboro, NJ, USA ABSTRACT The Bechdel test, used to examine the frequency and portrayal of women in film, consists of three criteria – (1) a movie must represent two or more women, (2) who have names and speak to each other, (3) about anything other than a man. In order to answer the research question “Based on the Bechdel test, how does the Avengers series portray their female characters compared to their male characters?”, this paper utilizes and extends beyond the Bechdel test by performing a conventional content analysis of same-gender conversations in four top-grossing superhero films – Mar- vel’s The Avengers (2012), Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015), Avengers: Infinity War (2018), and Avengers: Endgame (2019). By combining the simplicity of the Bechdel test with a qualitative approach to code dialogue, this paper illus- trates the underrepresentation of female characters and specific differences between the portrayal of men and women in modern Marvel films. While the films improved in the number of female characters and female-to-female conver- sations over time, there is still a small number of female-to-female conversations in these films compared to male-to- male conversations. Furthermore, while male characters rarely spoke to each other about women, female characters spoke to each other about men very often. Some common elements of dialogue for both male and female characters were worries about danger, discussions of violence, and insulting others.