Why Philip Morris USA V. Williams Left Juries Confused About Whose Injuries Can Be Considered When Determining Punitive Damages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii

Hawaii State Fire Council Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii Submitted to The Twenty-Eighth State Legislature Regular Session June 2015 2014 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarette Report to the Hawaii State Legislature Table of Contents Executive Summary .…………………………………………………………………….... 4 Purpose ..………………………………………………………………………....................4 Mission of the State Fire Council………………………………………………………......4 Smoking-Material Fire Facts……………………………………………………….............5 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarettes (RIPC) Defined……………………………......6 RIPC Regulatory History…………………………………………………………………….7 RIPC Review for Hawaii…………………………………………………………………….9 RIPC Accomplishments in Hawaii (January 1 to June 30, 2014)……………………..10 RIPC Future Considerations……………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….............15 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………17 Appendices Appendix A: All Cigarette Fires (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss Related to Cigarettes 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………18 Appendix B: Building Fires Caused by Cigarettes (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………………19 Appendix C: Cigarette Related Building Fires 2003 to 2013…………………………..20 Appendix D: Injuries/Fatalities Due To Cigarette Fire 2003 to 2013 ………………....21 Appendix E: HRS 132C……………………………………………………………...........22 Appendix F: Estimated RIPC Budget 2014-2016………………………………...........32 Appendix G: List of RIPC Brands Being Sold in Hawaii………………………………..33 2 2014 -

2020 Fourth-Quarter and Full-Year Results February 4, 2021

Delivering a Smoke-Free Future 2020 Fourth-Quarter and Full-Year Results February 4, 2021 Introduction • A glossary of key terms and definitions, including the definition for reduced-risk products, or "RRPs," additional heated tobacco unit market data, as well as adjustments, other calculations and reconciliations to the most directly comparable U.S. GAAP measures are at the end of today’s webcast slides, which are posted on our website • Unless otherwise stated, all references to IQOS are to our IQOS heat-not-burn devices and consumables • Comparisons presented on a like-for-like basis reflect pro forma 2019 results, which have been adjusted for the deconsolidation of our Canadian subsidiary, Rothmans, Benson & Hedges, Inc. (RBH), effective March 22, 2019 • Growth rates presented on an organic basis reflect currency-neutral underlying results and "like-for-like" comparisons, where applicable 2 Forward-Looking and Cautionary Statements • This presentation and related discussion contain projections of future results and other forward-looking statements. Achievement of future results is subject to risks, uncertainties and inaccurate assumptions. In the event that risks or uncertainties materialize, or underlying assumptions prove inaccurate, actual results could vary materially from those contained in such forward-looking statements. Pursuant to the “safe harbor” provisions of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, PMI is identifying important factors that, individually or in the aggregate, could cause actual results and -

Negativliste. Tobaksselskaber. Oktober 2016

Negativliste. Tobaksselskaber. Oktober 2016 Læsevejledning: Indrykket til venstre med fed tekst fremgår koncernen. Nedenunder, med almindelig tekst, fremgår de underliggende selskaber, som der ikke må investeres i. Alimentation Couche Tard Inc Alimentation Couche-Tard Inc Couche-Tard Inc Alliance One International Inc Alliance One International Inc Altria Group Inc Altria Client Services Inc Altria Consumer Engagement Services Inc Altria Corporate Services Inc Altria Corporate Services International Inc Altria Enterprises II LLC Altria Enterprises LLC Altria Finance Cayman Islands Ltd Altria Finance Europe AG Altria Group Distribution Co Altria Group Inc Altria Import Export Services LLC Altria Insurance Ireland Ltd Altria International Sales Inc Altria Reinsurance Ireland Ltd Altria Sales & Distribution Inc Altria Ventures Inc Altria Ventures International Holdings BV Batavia Trading Corp CA Tabacalera Nacional Fabrica de Cigarrillos El Progreso SA Industria de Tabaco Leon Jimenes SA Industrias Del Tabaco Alimentos Y Bebidas SA International Smokeless Tobacco Co Inc National Smokeless Tobacco Co Ltd Philip Morris AB Philip Morris Albania Sh pk Philip Morris ApS Philip Morris Asia Ltd Philip Morris Baltic UAB Philip Morris Belgium BVBA Philip Morris Belgium Holdings BVBA Philip Morris Belgrade doo Philip Morris BH doo Philip Morris Brasil SA Philip Morris Bulgaria EEOD Philip Morris Capital Corp Philip Morris Capital Corp /Rye Brook Philip Morris Chile Comercializadora Ltda Philip Morris China Holdings SARL Philip Morris China Management -

Complete Annual Report

Philip Morris International 2016 Annual Report THIS CHANGES EVERYTHING 2016 Philip Morris Annual Report_LCC/ANC Review Copy February 22 - Layout 2 We’ve built the world’s most successful cigarette company with the world’s most popular and iconic brands. Now we’ve made a dramatic decision. We’ve started building PMI’s future on breakthrough smoke-free products that are a much better choice than cigarette smoking. We’re investing to make these products the Philip Morris icons of the future. In these changing times, we’ve set a new course for the company. We’re going to lead a full-scale effort to ensure that smoke- free products replace cigarettes to the benefit of adult smokers, society, our company and our shareholders. Reduced-Risk Products - Our Product Platforms Heated Tobacco Products Products Without Tobacco Platform Platform 1 3 IQOS, using the consumables Platform 3 is based on HeatSticks or HEETS, acquired technology that features an electronic holder uses a chemical process to that heats tobacco rather Platform create a nicotine-containing than burning it, thereby 2 vapor. We are exploring two Platform creating a nicotine-containing routes for this platform: one 4 vapor with significantly fewer TEEPS uses a pressed with electronics and one harmful toxicants compared to carbon heat source that, once without. A city launch of the Products under this platform cigarette smoke. ignited, heats the tobacco product is planned in 2017. are e-vapor products – without burning it, to generate battery-powered devices a nicotine-containing vapor that produce an aerosol by with a reduction in harmful vaporizing a nicotine solution. -

Answer and Defenses of Respondent Altria Group, Inc., With

PUBLIC response to competition. Altria withdrew its e-vapor products because it concluded that they could not meet FDA’s regulatory requirements, because they lacked consumer appeal, and because they had lost money and had no short- or long-term path to profitability. The minority investment that the FTC challenges, which was designed to make JLI a more successful competitor by, among other things, helping it to successfully navigate complex regulatory hurdles and thereby continue selling its products, does not violate the antitrust laws. Altria submits that, on the full record, and in considering the applicable law, the relief sought by the Complaint should be denied. Altria’s subsidiary, Philip Morris USA, has for more than a century been one of the nation’s leading manufacturers of conventional, combustible cigarettes. In 2012, Altria established a new subsidiary, Nu Mark, to develop reduced-harm tobacco products, recognizing that adult consumers were becoming interested in e-vapor products because they could potentially provide some or all of the satisfaction of combustible cigarettes without the associated tar and without the stigma associated with smoking. Although Altria set up Nu Mark to compete, it did not have scientists or technical experts who were experienced in developing e-vapor products. After failing in its initial efforts to develop a successful product on its own, Altria undertook an acquisition strategy beginning in 2014. All of this was done at a time when the FDA did not regulate e-vapor products. Far from being a “threat to JLI’s market dominance” as the FTC alleges, Altria’s effort was a failure. -

PHILIP MORRIS USA PERSONNEL NUMBER ORGANIZATION’S CITY/STATE/ZIP CODE Please Include Any Leading Zeros

Part A: To be completed by donor FIRST/LAST NAME NAME OF ORGANIZATION RECEIVING GIFT PHILIP MORRIS USA PERSONNEL NUMBER ORGANIZATION’S CITY/STATE/ZIP CODE Please include any leading zeros. Your Philip Morris USA Personnel Number can be found by accessing My Info/My Staff through the Human Resources section on Philip Morris USA's intranet or on the stub of your payroll check in the box marked Employee ID. $ , .00 HOME ADDRESS CHECK IF NEW ADDRESS AMOUNT OF GIFT (MINIMUM $25) CITY/STATE/ZIP CODE EXACT DATE OF GIFT (MONTH/DAY/YEAR) CHECK CREDIT SECURITIES DEPARTMENT NAME # SHARES BUSINESS E-MAIL ADDRESS NAME OF COMPANY STOCK PERSONAL E-MAIL ADDRESS DAYTIME PHONE NUMBER EMPLOYEE CERTIFICATION: I am currently an eligible employee of Philip Morris USA. The information submitted is correct and my gift qualifies as a tax-deductible gift to a tax-exempt public charity recognized by the Internal Revenue Service under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. My gift has been paid and is a current, personal contribution and is not a future pledge. This is an individual gift and not pooled with funds belonging to others. Neither I nor my family will derive any direct or indirect financial or material benefit from this gift. My gift does not represent payment for service. I understand that misuse of the Philip Morris USA Matching Gifts Program will result in permanent revocation of my matching gifts privileges and may lead to other disciplinary actions, including termination. I have read and understand the Philip Morris USA Matching Gifts Program Guidelines, and I submit this request in accordance with them. -

Iowa Cigarette Brand List

Iowa Directory of Certified Tobacco Product Manufacturers and Brands PLEASE NOTE Flavored Cigarettes & RYO are now illegal. Regardless of being on this List. See footnote *(3) 7/2/19 Iowa Additions to the Directory (within the last six months) NPM This KT&G Corp. cigarettes 7/2/19 PM Leaf by Lane Ltd Scandinavian Tobacco Group Lane Ltd roll your own 6/24/19 PM Manitou Premier Manufacturing cigarettes 5/24/19 Deletions to the Directory (within the last six months) PM Custom Blends Wind River Tobacco Co., LLC roll your own 6/17/19 PM Fantasia Sherman 1400 Broadway NYC, Ltd. cigarettes 6/17/19 PM Rave ITG Brands, LLC roll your own 6/17/19 PM Roll Rich Scandinavian Tobacco Group Lane Ltd. roll your own 5/24/19 NPM Native Native Trading Associates cigarettes 5/13/19 NPM Native Native Trading Associates roll your own 5/13/19 NPM Market Smokin Joes cigarettes 2/6/19 NPM Smokin Joes Smokin Joes cigarettes 2/6/19 NPM Smokin Joes Smokin Joes roll your own 2/6/19 NPM Smokin Joes Natural Smokin Joes cigarettes 2/6/19 Type of Manufacturer is for Participating (PM) or Non-Participating (NPM) with the Master Settlement Agreement. TYPE BRAND MANUFACTURER PRODUCT DATE PM 1839 Premier Manufacturing cigarettes 10/1/14 PM 1839 Premier Manufacturing roll your own 10/1/14 NPM 24/7 Xcaliber International Ltd. cigarettes 12/13/18 PM American Bison Wind River Tobacco Co., LLC roll your own 7/22/03 NPM Aura Cheyenne International, LLC cigarettes 8/4/10 PM Bali Shag Top Tobacco, L.P. -

38 2000 Tobacco Industry Projects—A Listing (173 Pp.) Project “A”: American Tobacco Co. Plan from 1959 to Enlist Professor

38 2000 Tobacco Industry Projects—a Listing (173 pp.) Project “A”: American Tobacco Co. plan from 1959 to enlist Professors Hirsch and Shapiro of NYU’s Institute of Mathematical Science to evaluate “statistical material purporting to show association between smoking and lung cancer.” Hirsch and Shapiro concluded that “such analysis is not feasible because the studies did not employ the methods of mathematical science but represent merely a collection of random data, or counting noses as it were.” Statistical studies of the lung cancer- smoking relation were “utterly meaningless from the mathematical point of view” and that it was “impossible to proceed with a mathematical analysis of the proposition that cigarette smoking is a cause of lung cancer.” AT management concluded that this result was “not surprising” given the “utter paucity of any direct evidence linking smoking with lung canner.”112 Project A: Tobacco Institute plan from 1967 to air three television spots on smoking & health. Continued goal of the Institute to test its ability “to alter public opinion and knowledge of the asserted health hazards of cigarette smoking by using paid print media space.” CEOs in the fall of 1967 had approved the plan, which was supposed to involve “before-and-after opinion surveys on elements of the smoking and health controversy” to measure the impact of TI propaganda on this issue.”113 Spots were apparently refused by the networks in 1970, so plan shifted to Project B. Project A-040: Brown and Williamson effort from 1972 to 114 Project AA: Secret RJR effort from 1982-84 to find out how to improve “the RJR share of market among young adult women.” Appeal would 112 Janet C. -

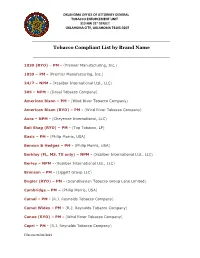

Tobacco Compliant List by Brand Name ______

OKLAHOMA OFFICE OF ATTORNEY GENERAL TOBACCO ENFORCEMENT UNIT 313 NW 21st STREET OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLAHOMA 73105-3207 _____________________________________________________________________________ Tobacco Compliant List by Brand Name _________________________________________ 1839 (RYO) – PM - (Premier Manufacturing, Inc.) 1839 – PM - (Premier Manufacturing, Inc.) 24/7 – NPM - (Xcaliber International Ltd., LLC) 305 – NPM - (Dosal Tobacco Company) American Bison – PM - (Wind River Tobacco Company) American Bison (RYO) – PM - (Wind River Tobacco Company) Aura – NPM - (Cheyenne International, LLC) Bali Shag (RYO) – PM - (Top Tobacco, LP) Basic – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Benson & Hedges – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Berkley (FL, MS, TX only) – NPM - (Xcaliber International Ltd., LLC) Berley – NPM - (Xcaliber International Ltd., LLC) Bronson – PM - (Liggett Group LLC) Bugler (RYO) – PM - (Scandinavian Tobacco Group Lane Limited) Cambridge – PM – (Philip Morris, USA) Camel – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Camel Wides – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Canoe (RYO) – PM - (Wind River Tobacco Company) Capri – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Effective 06/01/2021 Carlton – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Carnival – NPM - (KT&G Corporation) Chesterfield – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Cheyenne – NPM - (Cheyenne International, LLC) Crowns – PM - (Commonwealth Brands, Inc.) DTC – NPM - (Dosal Tobacco Company) Decade – NPM - (Cheyenne International, LLC) Doral – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Drum (RYO) – PM - (Top Tobacco, LP) Dunhill -

Last Updated 7/9/2015 Marlboro Ingredients by Packing

Marlboro Ingredients by Packing These lists identify ingredients that are added to tobacco at levels of 0.1% or more of the weight of the tobacco rod (the column of tobacco in each cigarette) of our cigarette products. The ingredients are in descending order by weight. Philip Morris USA manufactures its cigarettes in a variety of lengths. Cigarette length descriptors are used to identify different products. These length descriptors include (in order of increasing product length) 72mm, Kings, 100's and 120's. There are other ingredients added to tobacco at levels less than 0.1% in PM USA cigarettes, including the natural and artificial flavorings that give a cigarette product its unique characteristics, as well as ingredients in the non-tobacco components. Please view the Cigarette Non-Tobacco Ingredients document for composite lists. Marlboro100’s Box Marlboro 100’s Soft Pack • Tobacco • Tobacco • Water • Water • Sugars (Sucrose and/or Invert Sugar and/or • Sugars (Sucrose and/or Invert Sugar and/or High Fructose Corn Syrup) High Fructose Corn Syrup) • Propylene Glycol • Propylene Glycol • Glycerol • Glycerol • Licorice Extract • Licorice Extract • Diammonium Phosphate • Diammonium Phosphate • Ammonium Hydroxide • Ammonium Hydroxide • Cocoa and Cocoa Products • Cocoa and Cocoa Products • Carob Bean and Extract • Carob Bean and Extract • Natural and Artificial Flavors • Natural and Artificial Flavors Marlboro Box Marlboro 25’s Box • Tobacco • Tobacco • Water • Water • Sugars (Sucrose and/or Invert Sugar and/or • Sugars (Sucrose and/or -

Merit Ingredients by Packing

Merit Ingredients by Packing These lists identify ingredients that are added to tobacco at levels of 0.1% or more of the weight of the tobacco rod (the column of tobacco in each cigarette) of our cigarette products. The ingredients are in descending order by weight. Philip Morris USA manufactures its cigarettes in a variety of lengths. Cigarette length descriptors are used to identify different products. These length descriptors include (in order of increasing product length) 72mm, Kings, 100's and 120's. There are other ingredients added to tobacco at levels less than 0.1% in PM USA cigarettes, including the natural and artificial flavorings that give a cigarette product its unique characteristics, as well as ingredients in the non-tobacco components. Please view the Cigarette Non-Tobacco Ingredients document for composite lists. Merit Gold Pack 100’s Soft Pack Merit Gold Pack Box • Tobacco • Tobacco • Water • Water • Sugars (Sucrose and/or Invert Sugar and/or • Sugars (Sucrose and/or Invert Sugar and/or High Fructose Corn Syrup) High Fructose Corn Syrup) • Propylene Glycol • Propylene Glycol • Glycerol Licorice Extract • Glycerol • Diammonium Phosphate • Licorice Extract • Ammonium Hydroxide • Diammonium Phosphate • Cocoa and Cocoa Products • Ammonium Hydroxide • Carob Bean and Extract • Cocoa and Cocoa Products • Natural and Artificial Flavors • Carob Bean and Extract • Natural and Artificial Flavors Merit Gold Pack Soft Pack Merit Menthol Gold Pack 100’s Soft Pack • Tobacco • Tobacco • Water • Water • Sugars (Sucrose and/or Invert -

Iowa Cigarette Brand List

Iowa Directory of Certified Tobacco Product Manufacturers and Brands PLEASE NOTE Flavored Cigarettes & RYO are now illegal. Regardless of being on this List. See footnote *(3) 8/12/20 Iowa Additions to the Directory (within the last six months) PM Nat's Philip Morris USA cigarettes 8/12/20 PM Montego Liggett Group Inc. cigarettes 6/8/20 Deletions to the Directory (within the last six months) PM Nat's Sherman 1400 Broadway NYC, Ltd. cigarettes 8/12/20 PM Ace King Maker Marketing cigarettes 5/7/20 PM Dreams Kretek International cigarettes 5/7/20 PM Gold Crest King Maker Marketing cigarettes 5/7/20 PM Wings Japan Tobacco International cigarettes 5/7/20 Type of Manufacturer is for Participating (PM) or Non-Participating (NPM) with the Master Settlement Agreement. TYPE BRAND MANUFACTURER PRODUCT DATE PM 1839 Premier Manufacturing cigarettes 10/1/14 PM 1839 Premier Manufacturing roll your own 10/1/14 NPM 24/7 Xcaliber International Ltd. cigarettes 12/13/18 PM American Bison Wind River Tobacco Co., LLC roll your own 7/22/03 NPM Aura Cheyenne International, LLC cigarettes 8/4/10 PM Bali Shag Top Tobacco, L.P. roll your own 11/9/18 PM Baron American Blend Farmers Tobacco Company of Cynthiana, Inc. cigarettes 9/20/05 PM Basic Philip Morris USA cigarettes 7/22/03 PM Benson & Hedges Philip Morris USA cigarettes 7/22/03 NPM Berley Xcaliber International Ltd. cigarettes 12/13/18 PM Black & Gold Sherman 1400 Broadway NYC, Ltd. cigarettes 7/22/03 PM Bronson Liggett Group Inc cigarettes 4/11/06 PM Bugler Scandinavian Tobacco Group Lane Ltd.