TRINIDAD and TOBAGO URBAN REGENERATION and REVITALIZATION PROGRAMME (TT-T1086 and TT- L1057)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gazette No. 119 of 2008.Pdf

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO GAZETTE VOL . 47 Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, Thursday 14th August, 2008—Price $1.00 NO. 119 NO.GAZETTE NOTICE PAGE NO.GAZETTE NOTICE PAGE 1407 Notice re Supplement ……………845 1417 Central Bank, Weekly Statement of Account as at 850 6th August, 2008 Appointments— 1418 Application for the Grant of a New Licence under 851 1408 To act as Minister of Information ……845 the Gambling and Betting Act 1409 To act as Minister of Science, Technology and 845 Tenders— Tertiary Education 1419 For the Supply and Delivery of Mechanical 851 1410 To act as Minister of Agriculture, Land and 846 Equipment to the Highways Division— Marine Resources Ministry of Works and Transport 1411 –12 Appointment of Private Warehouses …… 1420 For the Design and Construction of a 852 846 Pre-Fabricated Office Building for the 1413 Hindu Marriage Officer’s Licence Granted … 846 Tunapuna/Piarco Regional Corporation— 1414 Grant of Certificates of Registration ……847 Ministry of Local Government 1415 Registration of a Minor—Oath of Allegiance … 1421 Extension of closing date of Tender for the 852 847 Development of Recreational Facilities for 1416 Probate and Letters of Administration— 847 the Arima Borough Corporation—Ministry of Applications Local Government 1407 SUPPLEMENT TO THIS ISSUE THE DOCUMENTS detailed hereunder have been issued and are published as a Supplement to this issue of the Trinidad and Tobago Gazette: Legal Supplement Part B— T Notice of Declaration of Trinidad and Tobago Standards—(Legal Notice No. 131 of 2008). Notice of Variation of Trinidad and Tobago Standards—(Legal Notice No. 132 of 2008). Notice of Revocation of Trinidad and Tobago Standards—(Legal Notice No. -

Agencies Continue to Drive Relief Efforts to Support the People of St Vincent and the Grenadines

Agencies continue to drive relief efforts to support the people of St Vincent and the Grenadines (/content/agencies-continue-drive-relief-efforts-support-people-st-vincent-and-grenadines) Following the eruption of the La Soufrière Volcano, the Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, through the Office of Disaster Preparedness and Management (ODPM), is hosting a relief collection drive as part of our ongoing response and relief efforts in support of St Vincent and the Grenadines. Through this initiative, the national community can once again demonstrate our true Caribbean solidarity by providing much needed relief items to many persons and families during this critical time. Persons and organisations who are interested in donating to the relief collection drive are asked to follow the Immediate Needs List provided by the National Emergency Management Organisation of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. While we are aware that many persons would want to give many items in the spirit of humanitarianism, it is important that we do not send unsolicited supplies that may overwhelm the country’s logistics system (Please see the attached listing). To assist you in this venture, the ODPM with support from the Disaster Management Units of the Ministry of Rural Development and Local Government (MoRDLG), Tobago Emergency Management Agency (TEMA), and the Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA) International, has established a number of relief collection centres across Trinidad and Tobago (Please see the attached listing). For your convenience, relief items can be dropped off today (Saturday 10th April, 2021) at all centres and collection will resume on Monday 12th April, 2021. -

20191206, Eighth Report of the JSC

2 An electronic copy of this report can be found on the Parliament’s website: www.ttparliament.org The Joint Select Committee on Land and Physical Infrastructure Contact the Committees Unit Telephone: 624-7275 Extensions 2828/2425/2283, Fax: 625-4672 Email: [email protected] 3 Joint Select Committee on Land and Physical Infrastructure (including Land, Agriculture, Marine Resources, Public Utilities, Transport and Works) An inquiry into the Effectiveness of Measures in Place to Reduce Traffic Congestion on the Nation’s Roads. Eighth Report of Fifth Session 2019/2020, Eleventh Parliament Report, together with Minutes Ordered to be printed Date Laid Date Laid H.o.R: 6/12/2019 Senate: 7/12/2019 Published on ________ 201__ 4 THE JOINT SELECT COMMITTEE ON LAND AND PHYSICAL INFRASTRUCTURE Establishment 1. The Joint Select Committee on Land and Physical Infrastructure was appointed pursuant to section 66A of the Constitution of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. The House of Representatives and the Senate on Friday November 13, 2015 and Tuesday November 17, 2015, respectively agreed to a motion, which among other things, established this Committee. Current Membership 2. The following Members were appointed to serve on the Committee: Mr. Deoroop Teemal - Chairman1 Mr. Rushton Paray – Vice Chairman Mr. Franklin Khan Dr. Lovell Francis Mrs. Glenda Jennings-Smith Mr. Darryl Smith Mr. Nigel De Freitas2 Mr. Wade Mark3 Functions and Powers 3. The Committee is one of the Departmental Select Committees, the functions and powers of which are set out principally in Standing Orders 91 and 101 of the Senate and 101 and 111 of the House of Representatives. -

Gazette No. 183, Vol. 58, Thursday 19Th December, 2019

VOL. 58 Caroni, Trinidad, Thursday 19th December, 2019–Price $1.00 NO. 183 NO.GAZETTE NOTICE PAGE NO.GAZETTE NOTICE PAGE 2482 Notice re Supplements … … … 3085 2487 P robate and Letters of Administration– 3087 Applications 2483 Assent to Acts … … … … 3086 2488 Central Bank, Weekly Statement of Account as 3094 at 18th December, 2019 2484 Publication of Bill … … … … 3086 Loss of Policies– Appointments– 2489—92 Maritime Life (Caribbean) Limited Policies ... 3095 2485 To act as Minister of Public Administration … 3086 2493 Pan-American Life Insurance of (Trinidad and Tobago), Policies … … ... 3095 2486 To be Temporarily a member of the Senate … 3086 2494—95 Transfer of Licences … … … ... 3095 THE FOLLOWING HAVE BEEN ISSUED: ACT NO. 23 of 2019–“An Act to provide for the imposition or variation of certain duties and taxes and to introduce provisions of a fiscal nature and for related matters”–($1.60). ACT NO. 24 of 2019–“An Act to amend the Dangerous Drugs Act, Chap. 11:25”–($3.20). ACT NO. 25 of 2019–“An Act to amend the Criminal Law Act, Chap. 10:04, the Prisons Act, Chap. 13:01, the Police Service Act, Chap. 15:01, the Special Reserve Police Act, Chap. 15:03, the Immigration Act, Chap. 18:01, the Fire Service Act, Chap. 35:50 and the Customs Act, Chap. 78:01”–($9.60). BILL entitled “An Act to amend the Constitution (Prescribed Matters) Act, Chap. 1:02, the Interpretation Act, Chap. 3:01 and the Judicial and Legal Service Act, Chap. 6:01”–($1.20). 2482 SUPPLEMENTS TO THIS ISSUE THE DOCUMENTS detailed hereunder have been issued and are published as Supplements to this issue of the Trinidad and Tobago Gazette: Legal Supplement Part A– Act No. -

Trinidad and Tobago Postal Corporation

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO POSTAL CORPORATION SALE OF TRACKPAKS No. Shop Name Address Contact No Business Hours 17 Prince Street, Arima, 1 Arima 667-5363 Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm Trinidad and Tobago 9 St. Yves Street, 2 Chaguanas Chaguanas, 500699, 671-2254 Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm Trinidad & Tobago 2 Lucky Street, 3 La Romain La Romaine, 650199, 697-7110 Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm Trinidad & Tobago 240-250 Golden Grove Road, 669-5363 ext 4 N.M.C. Piarco 350462, Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm 102 Trinidad and Tobago 5 Eastern Main Road, Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm 5 San Juan San Juan, 250199, 675-9659 Trinidad & Tobago 29 St. Ann’s Road, 6 St. Ann’s St. Ann’s, 160299, 621-0759 Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm Trinidad & Tobago 61-63 Western Main Road, 7 St. James St. James, 180199, 622-9862 Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm Trinidad & Tobago 22-24 St. Vincent St, 8 St. Vincent St Port-of-Spain, 623-5042 Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm Trinidad and Tobago 177 Tragarete Road, Tragarete 9 Port of Spain, 100498, 622-3364 Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm Road Trinidad & Tobago 76-78 Eastern Main Road, Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm 10 Tunapuna Tunapuna, 330899, 645-3914 Trinidad & Tobago 13 Cypress Avenue, 11 Bon Accord Bon Accord, 910398, 639-1023 Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm Trinidad & Tobago Caroline Building 36 Wilson Road, 12 Scarborough 660-7377 Mon to Fri 8:00 am to 4:00 pm Scarborough, Tobago Sterlin Mc Alister, Sterlin's Electrical Supplies Ltd, Mon-Fri 8:00am -4:00pm 13 Coffee Street 653-7070 180 Coffee Street, San Fernando, Sat 8:00am-12:00pm -

Municipality of Tunapuna/Piarco

Municipality of Tunapuna/Piarco Local Area Economic Profile (Final Report) Municipality of Tunapuna/Piarco Local Area Economic Profile (Final Report) Submitted to: Permanent Secretary Ministry of Local Government Kent House, Maraval, Trinidad and Tobago Submitted by: Kairi Consultants Limited 14 Cochrane Street, Tunapuna, TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Tel: 1 868 663 2677; Fax: 1 868 663 1442 Email: [email protected] "Striving Towards Our Potential as the Premier Education and Knowledge Centre of the Southern Caribbean…" Contents List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... v List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................ vii Acronyms and Abbreviations................................................................................................................. ix Chapter 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 12 1.1 Limitations of the Study ........................................................................................................ 13 1.2 Content of the Tunapuna/Piarco Local Area Economic Profile ............................................ 13 Chapter 2 Area Information and Demography ..................................................................................... 14 2.1 Location ............................................................................................................................... -

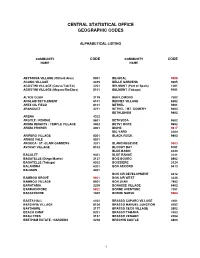

Community Codes

CENTRAL STATISTICAL OFFICE GEOGRAPHIC CODES ALPHABETICAL LISTING COMMUNITY CODE COMMUNITY CODE NAME NAME ABYSSINIA VILLAGE (Oilfield Area) 5301 BEJUCAL 9805 ACONO VILLAGE 3319 BELLE GARDENS 9605 AGOSTINI VILLAGE (Couva/Tab/Tal) 4201 BELMONT (Port of Spain) 1001 AGOSTINI VILLAGE (Mayaro/RioClaro) 5101 BELMONT (Tobago) 9101 ALYCE GLEN 3119 BEN LOMOND 7502 ANGLAIS SETTLEMENT 6101 BENNET VILLAGE 8202 APEX OIL FIELD 8101 BETHEL 9401 ARANGUEZ 3211 BETHEL / MT. GOMERY 9303 BETHLEHEM 9402 ARENA 4202 ARGYLE / KENDAL 9601 BETHSEDA 9502 ARIMA HEIGHTS / TEMPLE VILLAGE 3402 BETSY HOPE 9602 ARIMA PROPER 3001 BICHE 9817 BIG YARD 3104 ARIPERO VILLAGE 8301 BLACK ROCK 9403 ARNOS VALE 9501 AROUCA / ST. CLAIR GARDENS 3311 BLANCHISSEUSE 9803 AVOCAT VILLAGE 8102 BLOODY BAY 9701 BLUE BASIN 3130 BACOLET 9301 BLUE RANGE 3141 BAGATELLE (Diego Martin) 3127 BOIS BOURG 8402 BAGATELLE (Tobago) 9302 BOISSIERE 3124 BALANDRA 6301 BON ACCORD 9413 BALMAIN 4401 BON AIR DEVELOPMENT 3312 BAMBOO GROVE 9801 BON AIR WEST 3336 BAMBOO VILLAGE 8401 BON JEAN 7403 BARATARIA 3209 BONASSE VILLAGE 8403 BARRACKPORE 9802 BONNE AVENTURE 7301 BASSETERRE 7402 BORDE NARVE 9804 BASTA HALL 4402 BRASSO CAPARO VILLAGE 4101 BATCHYIA VILLAGE 8104 BRASSO MANUEL JUNCTION 4102 BAYSHORE 3117 BRASSO SECO VILLAGE 3502 BEACH CAMP 8201 BRASSO TAMANA 4103 BEAU PRES 3137 BRASSO VENADO 4104 BEETHAM ESTATE / GARDENS 3218 BRECHIN CASTLE 4403 1 CENTRAL STATISTICAL OFFICE GEOGRAPHIC CODES ALPHABETICAL LISTING COMMUNITY CODE COMMUNITY CODE NAME NAME BRICKFIELD 4203 CARMICHAEL 6501 BRICKFIELD / NAVET 5202 CARNBEE -

National Spatial Development Strategy for Trinidad and Tobago

National Spatial Development Strategy for Trinidad and Tobago Surveying the Scene 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction..................................................................................... 4 2. Population and Settlement Distribution..................................... 5 Geographic Distribution ........................................................................ 7 List of Figures Pattern and Form of Settlements........................................................... 9 Figure 1: Population Structure for 2000 and 3. Society and Culture........................................................................ 12 Forecast Change in 2020 and 2025 3.1 Crime................................................................................................ 12 3.2 Poverty............................................................................................. 14 Figure 2: Population Density by Administrative 3.3 Health............................................................................................... 16 Area, Trinidad and Tobago 2011 3.4 Housing............................................................................................ 17 Figure 3: Population Change by Administrative 3.5 Education......................................................................................... 18 Area 2000 – 2011 3.6 Cultural Heritage and Expression..................................................... 19 Figure 4: Distribution of Serious Crimes by 3.7 Recreation, Leisure and Sport......................................................... -

Speaking Notes of KPB – MNF Tunapuna

Speaking Notes of The Hon Kamla Persad Bissessar, MP, SC BA (Hons), Dip Ed, LLB (Hons), LEC, EMBA (Dist) Political Leader of the United National Congress and Leader of the Opposition of Trinidad and Tobago The UNC’s Monday Night Forum Kamla: “The UNC is a party for all of T&T. The principles that guide us – the safety and security of our families and the nation, opportunities for all, empowerment through education and skills development, integrity and good governance – these principles inspire our people to work together to help build a better future for our country. Tonight, I call on everyone, let us unite, let us work together to get T&T working again.” El Dorado West Secondary School Tunapuna Monday March 18, 2019 Good evening Tunapuna and Good evening Trinidad and Tobago. It’s hard to say that when the murder toll is 100 and a 71-year-old man can be gunned down in front a mall filled with families in broad daylight on a Sunday afternoon. Nevertheless, I am pleased to be back in Tunapuna tonight. On Saturday, we opened our brand-new East-West Corridor People Centre right here in Tunapuna I want to pay a special tribute to (list names) for making this possible. It is your hard work, sacrifice and dedication to the UNC that has made this new centre possible. This new East-West Corridor People Centre will serve as a hub of community development. Here, thanks to all the UNC family members who have stepped up to volunteer to serve their community, you will be able to access free health services, free legal advice, free resume writing and job advice and much more. -

STAMP RESELLERS AREA ADDRESS CONTACT Arima

STAMP RESELLERS AREA ADDRESS CONTACT Kopies Kraft Etc. 7 Woodford Street Arima 667-3585 ARIMA 300417 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO O'Meara Pharmacy 7 O'Meara Road 664-3246/ Arima ARIMA 301812 740-6015 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Hallmark Greetings Mid Centre Mall Chaguanas 13-39 Southern Main Road 665-8719/4715 CHAGUANAS 500624 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Edinburgh Variety Store & Gift Shop Southern Main Road Chaguanas Edinburgh Village 665-2730 CHAGUANAS 500325 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Richard H Sirjoo & Co. Ramsaran Street Chaguanas 671-4182 CHAGUANAS 500626 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO The Medicene Stop, #59 Rodney Road, Chaguanas Endeavour, 671-7654 CHAGUANAS 502154 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO DR&ASL, 71 La Clave Street, Chaguanas Montrose 672-8862 CHAGUANAS 500732 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Blu Darlin Company Limited #1 Nanan Street Couva Preysal Village 472-8601 COUVA 550233 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Coast Mini Mart 560 Southern Main Road Cunupia 755-3846 CUNUPIA 520209 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Cunupia Photocopy Centre and Gift Shop Chin Chin Road Cunupia 764-8760 CUNUPIA 520116 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Pharma Care Drugs #257 Eastern Main Road Curepe 645-1861 CUREPE 310706 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Josand Educational Institute #130 S.S Erin Road 712-6595/647- Debe DEBE 680216 2311 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Starlite Drugs Starlite Shopping Plaza 39-47 Diego Martin Main Road Diego Martin 632-0516 Four Roads DIEGO MARTIN 151707 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Diamond Vale Drugs Limited Diamond Vale Co-operative Shopping Plaza 1-11 Garnet Road Diego Martin 632-3459 Diamond Vale DIEGO MARTIN 150606 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO All Services Solutions Ltd Starlite Shopping Plaza Buliding 5 Diego Martin 39-47 Diego Martin Main Road, Unit 46 225-2229/2230 Four Roads DIEGO MARTIN 151707 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Ellen's Copy Centre #213 Eastern Main Road El Dorado El Dorado 742-5967 TUNAPUNA 330120 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Specialist Pharmacy Ltd. -

Regional Corporation Summary

ELECTIONS AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION ELECTORATE BY REGIONAL CORPORATIONS BOROUGH OF ARIMA ARIMA CENTRAL Polling Division Electorate 1975 525 1976 804 1980 655 1981 596 1982 655 2041 883 TOTAL 6 4118 ARIMA NORTHEAST Polling Division Electorate 2005 566 2010 274 2015 175 2020 348 2025 160 2030 432 2035 839 2040 567 2096 1045 TOTAL 9 4406 ELECTIONS AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION ELECTORATE BY REGIONAL CORPORATIONS BOROUGH OF ARIMA ARIMA WEST/O'MEARA Polling Division Electorate 1961 1109 1979 941 1985 756 1990 724 1991 416 TOTAL 5 3946 CALVARY Polling Division Electorate 1936 867 1937 531 1938 392 1946 374 1995 554 1996 536 2000 877 TOTAL 7 4131 MALABAR NORTH Polling Division Electorate 1965 864 1971 862 1972 425 1977 838 1978 1068 TOTAL 5 4057 ELECTIONS AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION ELECTORATE BY REGIONAL CORPORATIONS BOROUGH OF ARIMA MALABAR SOUTH Polling Division Electorate 1967 661 1968 602 1969 1124 1970 1192 1973 549 TOTAL 5 4128 TUMPUNA Polling Division Electorate 1966 954 1983 710 2045 762 2046 431 2047 763 2091 554 TOTAL 6 4174 ELECTIONS AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION ELECTORATE BY REGIONAL CORPORATIONS BOROUGH OF CHAGUANAS CHARLIEVILLE Polling Division Electorate 2750 1809 2755 1665 2875 1789 2880 1418 2885 264 2915 972 TOTAL 6 7917 CUNUPIA Polling Division Electorate 2705 995 2715 1060 2716 556 2718 381 2719 721 2770 592 2771 627 2772 645 2815 573 2816 447 2817 904 2818 493 TOTAL 12 7994 ELECTIONS AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION ELECTORATE BY REGIONAL CORPORATIONS BOROUGH OF CHAGUANAS EDINBURGH/LONGDENVILLE Polling Division Electorate 2800 1347 2835 -

Trincity Millennium Vision Trinidad and Tobago

Annika Fritz, Trincity Millennium Vision, 44 th ISOCARP Congress 2008 TRINCITY MILLENNIUM VISION TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 1 Annika Fritz, Trincity Millennium Vision, 44 th ISOCARP Congress 2008 INTRODUCTION Trinidad and Tobago, a twin island Republic are the two most southerly islands in the Caribbean; located between 10°3′N, 60°55′W and 10°50′N, 61°55′W as seen in Figure 1 below. Trinidad is located eleven (11) kilometers off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and its total land area is 5,128 km2 or 1,980 sq. miles. Tobago’s total land area on the other hand is estimated at 300 km2. The population of Trinidad and Tobago is approximately, one million two hundred and sixty-two thousand three hundred and sixty-six persons. (1 262 366) (http://www.cso.gov.tt/statistics/cssp/census2000/default.asp ). Its economy is very reliant on petrochemicals but is described as being diversified. Private individuals own 47% of the land while the State owns the remaining 53%, much of which is forest reserves (Smart 1988; Stanfield and Singer, 1993). The average population growth rate for the period 2000-2005 was 0.3%; the unemployment rate measured at the fourth quarter of 2006 was 5.0% (http://www.cso.gov.tt ). Source: www.ajmtours.com/maps.html Figure 1: Trinidad and Tobago within the larger Caribbean Context The islands of Trinidad and Tobago were both former British colonies. As a consequence, their political system, institutional and administrative structures reflect a British tradition. The construct of its land use planning system, is quite archaic as it is based on the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act of England and Wales .