Hermitage Castle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Soils Round Jedburgh and Morebattle

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOR SCOTLAND MEMOIRS OF THE SOIL SURVEY OF GREAT BRITAIN SCOTLAND THE SOILS OF THE COUNTRY ROUND JEDBURGH & MOREBATTLE [SHEETS 17 & 181 BY J. W. MUIR, B.Sc.(Agric.), A.R.I.C., N.D.A., N.D.D. The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research ED INB URGH HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE '956 Crown copyright reserved Published by HER MAJESTY’SSTATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased from 13~Castle Street, Edinburgh 2 York House, Kingsway, Lond6n w.c.2 423 Oxford Street, London W.I P.O. Box 569, London S.E. I 109 St. Mary Street, Cardiff 39 King Street, Manchester 2 . Tower Lane, Bristol I 2 Edmund Street, Birmingham 3 80 Chichester Street, Belfast or through any bookseller Price &I 10s. od. net. Printed in Great Britain under the authority of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Text and half-tone plates printed by Pickering & Inglis Ltd., Glasgow. Colour inset printed by Pillans & Ylson Ltd., Edinburgh. PREFACE The soils of the country round Jedburgh and Morebattle (Sheets 17 and 18) were surveyed during the years 1949-53. The principal surveyors were Mr. J. W. Muir (1949-52), Mr. M. J. Mulcahy (1952) and Mr. J. M. Ragg (1953). The memoir has been written and edited by Mr. Muir. Various members of staff of the Macaulay Institute for Soil Research have contributed to this memoir; Dr. R. L. Mitchell wrote the section on Trace Elements, Dr. R. Hart the section on Minerals in Fine Sand Fractions, Dr. R. C. Mackenzie and Mr. W. A. Mitchell the section on Minerals in Clay Fractions and Mr. -

Newcastleton Land Management Plan 2020 - 2030

Newcastleton Land Management Plan 2020 - 2030 Property Details Property Name: Newcastleton Grid Reference (main NY 5037 8728 Nearest town or Newcastleton forest entrance): locality: Local Authority: Scottish Borders Applicant’s Details Title: Mr Forename: John Surname: Ogilvie Position: Planning Forester Contact Number: 0131 370 5276 Email: [email protected] Address: Forestry and Land Scotland, Selkirk Office, Weavers Court, Forest Mill, Selkirk Postcode: TD7 5NY Owner’s Details (if different from Applicant) Name: Address: 1. I apply for Land Management Plan approval for the property described above and in the enclosed Land Management Plan. 2. I apply for an opinion under the terms of the Forestry (Environmental Impact Assessment) (Scotland) Regulations 2017 for afforestation / deforestation / roads / quarries as detailed in my application. 3. I confirm that the scoping, carried out and documented in the Consultation Record attached, incorporated those stakeholders which the FC agreed must be included. Where it has not been possible to resolve specific issues associated with the plan to the satisfaction of the consultees, this is highlighted in the Consultation Record. 4. I confirm that the proposals contained in this plan comply with the UK Forestry Standard. 5. I undertake to obtain any permissions necessary for the implementation of the approved Plan. Signed, Signed, Regional Manager Conservator FLS Region South SF Conservancy South Date Date of Approval Date Approval Ends 2 | Newcastleton LMP | John Ogilvie | February -

Notes on the Folk-Lore of the Northern Counties of England and The

S*N DIEGO) atitty, ESTABLISHED IN . THE YEAK MDCCCLXXVIII Alter et Idem. PUBLICATIONS OF THE FOLK-LOKE SOCIETY. II. LONDON: PRINTED BY NICHOLS AND SONS, STREET. 25, PARLIAMENT FOLK-LORE OP THE NORTHERN COUNTIES OF ENGLAND AND THE BORDERS. A NEW EDITION WITH MANY ADDITIONAL NOTES. BY WILLIAM HENDERSON, AUTHOR OF " MY LIFE AS AN ANGLER." " Our mothers' maids in our childhood . have so frayed us with hullbeggars, spirits, witches, urchins, elves, hags, fairies, satyrs, pans, faunes, sylvans.kit-with-the-candlestick (will-o'-the-wisp), tritons (kelpies), centaurs, dwarfs, giants, imps, calcars (assy-pods), conjurors, nymphs, changelings, incubus, Rohin-Goodfellow (Brownies), the spoorey, the man in the oak, the hellwain, the firedrake (dead light), the Puckle, Tom Thumb, Hobgoblin, Tom Tumbler, Bouclus, and such other bug- bears, that we are afraid of our own shadows." REGINALD SCOTT. LONDON: PUBLISHED FOR THE FOLK-LORE SOCIETY BY W. SATCHELL, PEYTON AND CO., 12, TAVISTOCK STREET, COVENT GARDEN. W.C. 1879. TO THE MOST HONOURABLE THE MARQUESS OF LONDONDERRY, IN EEMEMBRANCE OF MUCH KINDNESS AND OF MANY PLEASANT HOURS SPENT TOGETHER, THIS VOLUME IS, BY PERMISSION, INSCRIBED WITH EVERY SENTIMENT OE RESPECT AND ESTEEM BY HIS LORDSHIP'S ATTACHED FRIEND, WILLIAM HENDERSON. VI The Council of the Folk-Lore Society, in issuing this work as one of the publications for the year 1879, desire to point out to the Members 'that it is chiefly owing to the generous proposal of Mr. Henderson they arc enabled to produce in the second year of the Society's existence a book so much appreciated by the Folk-Lore student. -

Frommer's Scotland 8Th Edition

Scotland 8th Edition by Darwin Porter & Danforth Prince Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers About the Authors Darwin Porter has covered Scotland since the beginning of his travel-writing career as author of Frommer’s England & Scotland. Since 1982, he has been joined in his efforts by Danforth Prince, formerly of the Paris Bureau of the New York Times. Together, they’ve written numerous best-selling Frommer’s guides—notably to England, France, and Italy. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5744 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for per- mission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. -

Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plans

Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plans 1 2 Contents Page 2 Chairman’s Introduction Page 3 Arthuret Community Plan Introduction Page 4 Kirkandrews-on-Esk Plan Introduction Page 5 Arthuret Parish background and History Page 7 Brief outline of Kirkandrews on Esk Parish and History Page 9 Arthuret Parish Process Page 12 Kirkandrews on Esk Parish Process Page 18 The Action Plan 3 Chairman’s Introduction Welcome to the Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan – a joint Community Action Plan for the parishes of Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk. The aim is to encourage local people to become involved in ensuring that what matters to them – their ideas and priorities – are identified and can be acted upon. The Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan is based upon finding out what you value in your community. Then, based upon the process of consultation, debate and dialogue, producing an Action Plan to achieve the aspirations of local people for the community you live and work in. The consultation process took several forms including open days, questionnaires, workshops, focus group meetings, even a business speed dating event. The process was interesting, lively and passionate, but extremely important and valuable in determining the vision that you have for your community. The information gathered was then collated and produced in the following Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan. The Action Plan aims to show a balanced view point by addressing the issues that you want to be resolved and celebrating the successes we have achieved. It contains a range of priorities from those which are aspirational to those that can be delivered with a few practical steps which will improve life in our community. -

Kirkandrews on Esk: Introduction1

Victoria County History of Cumbria Project: Work in Progress Interim Draft [Note: This is an incomplete, interim draft and should not be cited without first consulting the VCH Cumbria project: for contact details, see http://www.cumbriacountyhistory.org.uk/] Parish/township: KIRKANDREWS ON ESK Author: Fay V. Winkworth Date of draft: January 2013 KIRKANDREWS ON ESK: INTRODUCTION1 1. Description and location Kirkandrews on Esk is a large rural, sparsely populated parish in the north west of Cumbria bordering on Scotland. It extends nearly 10 miles in a north-east direction from the Solway Firth, with an average breadth of 3 miles. It comprised 10,891 acres (4,407 ha) in 1864 2 and 11,124 acres (4,502 ha) in 1938. 3 Originally part of the barony of Liddel, its history is closely linked with the neighbouring parish of Arthuret. The nearest town is Longtown (just across the River Esk in Arthuret parish). Kirkandrews on Esk, named after the church of St. Andrews 4, lies about 11 miles north of Carlisle. This parish is separated from Scotland by the rivers Sark and Liddel as well as the Scotsdike, a mound of earth erected in 1552 to divide the English Debatable lands from the Scottish. It is bounded on the south and east by Arthuret and Rockcliffe parishes and on the north east by Nicholforest, formerly a chapelry within Kirkandrews which became a separate ecclesiastical parish in 1744. The border with Arthuret is marked by the River Esk and the Carwinley burn. 1 The author thanks the following for their assistance during the preparation of this article: Ian Winkworth, Richard Brockington, William Bundred, Chairman of Kirkandrews Parish Council, Gillian Massiah, publicity officer Kirkandrews on Esk church, Ivor Gray and local residents of Kirkandrews on Esk, David Grisenthwaite for his detailed information on buses in this parish; David Bowcock, Tom Robson and the staff of Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle; Stephen White at Carlisle Central Library. -

Kelso Town Trail.Indd

ke elso town trail . k lso n trail . k elso town tra to lso tow il . kelso wn ail . ke town t tr wn tr introductionrail . ail lso to kelso . kel il . ke tow so t n tra n t w own tow Scottish Borders Council has created which houses the Visitorra Infilor. mation Centre. to trai lso kel so l . kelso town trail . ke the Kelso Town Trail and would like to For those with more time, extensionsso t too wthe l . kel acknowledge and thank Mr Charles Denoon Trail which would add to the enjoyment ofn trail . kelso town trai for kindly allowing the use of material from the walk are suggested in the text. the Kelso Community Website (www.kelso. bordernet.co.uk/walks). The aim of the trail is In order to guide the visitor, plaques are sited to provide the visitor to Kelso with an added along the route at specific points of interest dimension to local history and a flavour of and information relating to them can be the town’s development, in particular, the found within this leaflet. As some of the sites historical growth of the town, its buildings along the Trail are houses, we would ask you and other items of interest. Along the route to respect the owners’ privacy. there is the opportunity to view structures which may be as old as the 12th century or We hope you will enjoy walking around as new as the year 2000, but all show the Kelso Town Trail and trust that you will have a architectural richness which together make pleasant stay in the town. -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Sir Bobby Charlton

EDUCATION PACK 2019 Activity 1 Matchbox Memories Activity 2 A Living For Northumberland Day 2019, we are running Northumbrian Legend ‘Matchbox Memories’ - an initiative with which we would like to get schools involved. – Sir Bobby Charlton We are inviting schoolchildren to write their favourite memory of Northumberland, so far in their lives, on a plain white matchbox. Alternatively, they could write it on a piece of paper and a teacher could then write on the boxes, as these are quite small. Another option is for children to take a matchbox home and collect a matchbox memory from a parent, or elderly family member. In this way, they can take part in an oral history exercise. We then wish to collect the memory boxes and put as many as possible on display. The children can add their name, or the name of the person who has given them their special memory, if they wish. We have a limited number of matchbox memory boxes available, but they can be bought at Amazon, if needs be. We could also possibly partner a school with a local sponsor, if we can find one for you. We’d love to have pictures of children working on their matchbox memories, or all holding one aloft for a photo. We will try to arrange for certain collection points, if you take part. This is a very special way to being generations together and find out what people have found special about Northumberland, past and present. We hope you have fun with it. One of the most famous Northumbrians alive today is a footballing legend and one of the few Englishmen to have won the World Cup football trophy. -

Scottish Folk Tales Free Download

TALES OF THE SEAL PEOPLE: SCOTTISH FOLK TALES FREE DOWNLOAD Duncan Williamson | 160 pages | 01 Mar 1998 | Interlink Publishing Group, Inc | 9780940793996 | English | Massachusetts, United States Scottish Fairy Tales, Folk Tales and Fables Johan rated it really liked it Nov 20, Hide Your feedback is much appreciated. Great imagery. Brownie A Tales of the Seal People: Scottish Folk Tales term for fairies in England and Scotland, they were generally benevolent but could turn bad if they were neglected. Thank you! The Fiddler and the Bogle of Bogandoran James Dane on Who are the Picts? Brown Man of the Muirs A supernatural guardian of the wild creatures from the Border region of Scotland. Gaels migrated into Scotland from Ireland until the Norsemen began their raids on the Scottish coast, and the stories of Fingal would doubtless have come across too. The seal people represent all that is gentle and loving about the vast waters, but they are also shape changers and can disappear without warning, making them the perfect characters Tales of the Seal People: Scottish Folk Tales star in the romantic tragedies of folklore. Blog at WordPress. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. The Laird harnessed the strength of the horse-form Kelpie by using halter stamped with the sign of a cross. More filters. Mauns' Stane Daoine Shie, or the Men of Peace Tales once abounded of a man who found a beautiful female selkie sunbathing on a beach, stole her skin and forced her to become his Tales of the Seal People: Scottish Folk Tales and bear his children. -

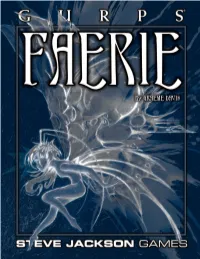

Faerie Is a Complete Guide to the Other Folk, Be Used with Any Game System

They lie, steal, kidnap, maim, and kill . and we put them in nurseries. They have been described as gods, demons, fallen angels, and ghosts – even aliens – but no one truly knows what they are. All through history, all around the world, they have been in the shadows, behind the trees, beneath the hills – and yes, even under the bed. Some are pretty, delicate little people with gossamer wings. But others are ten feet tall with a taste for human GURPS Basic Set, Third flesh, or wizened horrors with blue skins and claws of Edition Revised and GURPS iron. Some strike down those who unwittingly break Compendium I are required to use this supplement in a their laws. Others kill just for fun. GURPS campaign. The information in this book can GURPS Faerie is a complete guide to the Other Folk, be used with any game system. covering traditions from around the world. It describes their magic and worlds, and provides templates for THE STORYTELLERS: different faerie types and for the mortals who know them. You can incorporate the beautiful and sinister Fair Written by Ones into almost any existing game setting, or create a Graeme Davis new campaign set in the Unseelie Realms and beyond. Edited by Kimara Bernard Just keep cold iron and scripture close to hand, believe the opposite of what you hear, and don’t trust anything Illustrated by you see. Alex Fernandez And whatever you do, FIRST EDITION,FIRST PRINTING don’t eat their food. PUBLISHED OCTOBER 2003 ISBN9!BMF@JA:RSURQRoY`Z]ZgZnZ` 1-55634-632-8 Printed in SJG02295 6043 the USA By Graeme Davis Edited by Kimara Bernard Illustrated by Alex Fernandez Additional material by James L.