LEGO® Universe: Death of a Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Lego Constructs a Cross-Promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2013 How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games David Robert Wooten University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Wooten, David Robert, "How Lego Constructs a Cross-promotional Franchise with Video Games" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2013 ABSTRACT HOW LEGO CONSTRUCTS A CROSS-PROMOTIONAL FRANCHISE WITH VIDEO GAMES by David Wooten The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Michael Newman The purpose of this project is to examine how the cross-promotional Lego video game series functions as the site of a complex relationship between a major toy manufacturer and several media conglomerates simultaneously to create this series of licensed texts. The Lego video game series is financially successful outselling traditionally produced licensed video games. The Lego series also receives critical acclaim from both gaming magazine reviews and user reviews. By conducting both an industrial and audience address study, this project displays how texts that begin as promotional products for Hollywood movies and a toy line can grow into their own franchise of releases that stills bolster the original work. -

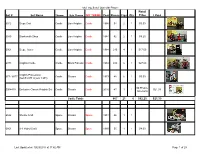

Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid

My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 6012 Siege Cart Castle Lion Knights Castle 1986 54 2 1 $3.50 6040 Blacksmith Shop Castle Lion Knights Castle 1984 92 2 1 $9.25 6061 Siege Tower Castle Lion Knights Castle 1984 216 4 1 $17.50 6073 Knights Castle Castle Black Falcons Castle 1984 410 6 1 $27.00 Knights Procession 677 / 6077 Castle Classic Castle 1979 48 6 1 $5.00 (Set # 6077 is year 1981) $0 Promo- 5004419 Exclusive Classic Knights Set Castle Classic Castle 2016 47 1 1 $21.39 Giveaway Castle Totals 867 21 6 $62.25 $21.39 6842 Shuttle Craft Space Classic Space 1981 46 1 1 6861 X-1 Patrol Craft Space Classic Space 1980 55 1 1 $4.00 Last Updated on 10/29/2017 at 11:42 AM Page 1 of 29 My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 6880 Surface Explorer Space Classic Space 1982 82 1 1 $7.50 6927 All Terrain Vehicle Space Classic Space 1981 170 2 1 $14.50 452 Mobile Tracking Station Space Classic Space 1979 76 1 1 462 Rocket Launcher Space Classic Space 1978 76 2 1 483 Alpha 1 Rocket Base Space Classic Space 1978 187 3 1 Space Totals 692 11 7 $26.00 $0.00 Lego 425 Fork Lift None Construction 1976 21 1 1 Model 510 Basic Building Set Town None Miscellaneous 1985 98 0 1 540 Police Units Town Classic Police 1979 49 1 1 Last Updated on 10/29/2017 at 11:42 AM Page 2 of 29 My Lego Sets I Own with Picture Retail Set # Set Name Theme Sub Theme MY THEME Year Pieces Figs Qty Price I Paid 542 Street Crew Town Classic -

Annual Report 2003 LEGO Company CONTENTS

Annual Report 2003 LEGO Company CONTENTS Report 2003 . page 3 Play materials – page 3 LEGOLAND® parks – page 4 LEGO Brand Stores – page 6 The future – page 6 Organisation and leadership – page 7 Expectations for 2004 – page 9 The LEGO® brand. page 11 The LEGO universe and consumers – page 12 People and Culture . page 17 The Company’s responsibility . page 21 Accounts 2003. page 24 Risk factors – page 24 Income statement – page 25 Notes – page 29 LEGO A/S Board of Directors: Leadership Team: * Mads Øvlisen, Chairman Dominic Galvin (Brand Retail) Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, Vice Chairman Tommy G. Jespersen (Supply Chain) Gunnar Brock Jørgen Vig Knudstorp (Corporate Affairs) Mogens Johansen Søren Torp Laursen (Americas) Lars Kann-Rasmussen Mads Nipper (Innovation and Marketing) Anders Moberg Jesper Ovesen (Corporate Finance) Henrik Poulsen (European Markets & LEGO Trading) President and CEO: Arthur Yoshinami (Asia/Pacific) Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen Mads Ryder (LEGOLAND parks) * Leadership Team after changes in early 2004 LEGO, LEGO logo, the Brick Configuration, Minifigure, DUPLO, CLIKITS logo, BIONICLE, MINDSTORMS, LEGOLAND and PLAY ON are trademarks of the LEGO Group. © 2004 The LEGO Group 2 | ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Annual Report 2003 2003 was a very disappointing year for LEGO tional toy market stagnated in 2003, whereas Company. the trendier part of the market saw progress. Net sales fell by 26 percent from DKK 11.4 bil- The intensified competition in the traditional lion in 2002 to DKK 8.4 billion. Play material toy market resulted in a loss of market share sales declined by 29 percent to DKK 7.2 bil- in most markets – partly to competitors who lion. -

Legoland® California Resort Announces Reopening April 1!

Media Contacts: Jake Gonzales /760-429-3288 [email protected] AWESOME IS BACK! LEGOLAND® CALIFORNIA RESORT ANNOUNCES REOPENING APRIL 1! Park Preview Days April 1-12 Includes access to select rides and attractions Resort officially reopens April 15 to include SEA LIFE® aquarium and LEGO® CHIMA™ Water Park Priority access to hotel guests, pass holders and existing ticket holders to be first Park guests in April With limited capacities, guests are required to book online in advance Resort is implementing safety guidelines LINK TO IMAGES: https://spaces.hightail.com/space/nMvjw0kEAr LINK TO BROLL: https://spaces.hightail.com/space/cNda6CmOIX CARLSBAD, Calif. (March 19, 2021) – LEGOLAND® California Resort is excited to offer Park Preview Days with access to select rides and attractions beginning April 1, 2021, under California’s reopening health and safety guidelines with official reopening on April 15, 2021. After closing its gates one year ago, the theme park built for kids is offering priority access to Hotel guests, pass holders and existing ticket holders impacted by COVID- 19 Park closure, for the month of April. Park Preview Days offers access to select rides including Driving School, LEGO® TECHNIC™ Coaster, Fairy Tale Brook and Coastersaurus. Kids and families can also enjoy socially distant character meet and greets, live entertainment, a wide variety of food options and Miniland U.S.A. The Resort officially reopens April 15, offering access to SEA LIFE® aquarium and LEGO® CHIMA™ Water Park. Guests will once again be immersed into the creative world of LEGO® and some of the Park’s more than 60 rides, shows and attractions. -

Rise of the LEGO® Digital Creator

Rise of the LEGO® Digital Creator While you’ve always been able to build your own physical creations with a bucket of LEGO® bricks, the route to the same level of digital LEGO freedom for fans has taken a bit longer. The latest step in that effort sees the LEGO Group teaming up with Unity Technologies to create a system that doesn’t just allow anyone to make a LEGO video game, it teaches them the process. The Unity LEGO Microgame is the most recent microgame created by Unity with the purpose of getting people to design their own video game. But in this case, the interactive tutorial turns the act of creation into a sort of game in and of itself, allowing players to simply drag and drop LEGO bricks into a rendered scene and use them to populate their vision. Designers can even give their LEGO brick creations life with intelligent bricks that breath functionality into any model to which they’re attached. Users can even create LEGO models outside of the Unity platform using BrickLink Studio, and then simply drop them into their blossoming game. While this is just the beginning of this new Unity-powered toolset for LEGO fans, it’s destined to continue to grow. The biggest idea that could come to the Unity project is the potential ability for a fan to share their LEGO video game creations with one another and vote on which is the best, with an eye toward the LEGO Group officially adopting them and potentially releasing them with some of the profit going back to the creator. -

Download Press Release

For Immediate Release Media Contacts: Jake Gonzales/760-918-5379 LEGOLAND® CALIFORNIA RESORT ANNOUNCES BIGGEST PARK ADDITION: THE LEGO® MOVIE™ WORLD! Family Theme Park and Warner Bros. Consumer Products Unveil New Rides, Attractions and Iconic LEGO Characters for 2020! LINK TO ART: https://spaces.hightail.com/space/UsoTZWbIm4 LINK TO IMAGES: https://spaces.hightail.com/space/uCKBaVi2g8 LINK TO BROLL: https://spaces.hightail.com/space/2w5rcshZ6S CARLSBAD, Calif. (August 15, 2019) –The audience erupted in cheer and confetti filled the theater as LEGOLAND® California Resort unveiled its biggest gift for its 20th birthday by announcing the largest addition in the Park’s history: The LEGO® MOVIE™ WORLD. General Manager Peter Ronchetti is excited to take guests from theater to theme park in 2020. “The LEGO MOVIE WORLD is LEGOLAND California Resort’s largest Park addition ever and we are thrilled to create an interactive experience that fully immerses guests into a world that was so brilliantly created by LEGO and celebrated by the hugely popular LEGO film franchise from our friends at Warner Bros.,” said Ronchetti. “We can’t wait to see the faces on all the children as they interact within the creative world of Bricksburg and experience the incredible Masters of Flight ride which is taking the traditional soaring-type of ride to new heights.” On the flagship ride Masters of Flight, guests hop aboard Emmet’s triple decker flying couch for a thrill- seeking adventure. The flying theater attraction whisks guests away on a suspended ride with a full- dome virtual screen, giving the sensational feeling of flying above memorable lands such as Middle Zealand, Cloud Cuckoo Land, Pirates Cove and Outer Space. -

Happy Holidays!

GREAT GIFT HAPPY HOLIDAYS! Light brick IDEAS! Press down on the chimney- Holiday Sets smoke button AGES 6+ 1 to set the fire aglow! Gingerbread House LEGO® WHAT’S NEW? Harry Potter Check out the new holiday sets: Gingerbread House, 10267 AGES 12+ 1,477 PIECES AGES 7+ 5 R E E LE® Star Wars™ Enjoy a festive build-and-play experience with the LEGO® Creator LEGO® sets, LEGO Disney Frozen II sets and more! Expert 10267 Gingerbread House. A treasure chest of magical details, this amazing model features frosted roofs with colorful candy buttons Creator Expert AGES 12+ 8 and a delicious facade with candy-cane columns, glittery windows BENEFITS & SERVICE and a tall chimney stack with a glowing fireplace. Inside the house ® When you purchase from the official LEGO® Shop, there’s an array of fun details and candy furnishings including LEGO Disney a tasteful bedroom with chocolate bed and cotton-candy AGES 5+ 12 LE lamp, and a bathroom with the essential toilet and bathtub. P This wonderful LEGO Gingerbread House sets the scene ® for imaginative adventures with the gingerbread family. THE LEGO MOVIE 2™ Children can light up the cozy fireplace, help clear the AGES 6+ 14 sidewalk with the snowblower and nestle the gingerbread Free Shipping every day on orders over $35! Visit LEGO.com/shipping for complete shipping details. baby in its carriage. It also includes a decorated Christmas tree with wrapped gifts and LEGO® Technic™ toys, including a rocking horse and a toy train. AGES 9+ 16 Exclusive Free Gifts with your order! This advanced LEGO set delivers Check LEGO.com or ask a Store Associate for details and purchase a challenging and rewarding ® A LEGO building experience and Architecture makes a great seasonal AGES 8+ 20 LEGO® VIP Tour the new VIP program, centerpiece for the home or office. -

GCSE MEDIA STUDIES Factsheet

GCSE MEDIA STUDIES Factsheet The Lego Movie Video Game: Industry and Audience DISCLAIMER This resource was designed using the most up to date information from the specification at the time it was published. Specifications are updated over time, which means there may be contradictions between the resource and the specification, therefore please use the information on the latest specification at all times. If you do notice a discrepancy please contact us on the following email address: [email protected] www.ocr.org.uk/mediastudies Media industries The following subject content needs to be studied in relation to The Lego Movie Video Game: Key idea Learners must demonstrate and apply their knowledge and understanding of: Media producers • the nature of media production, including by large organisations, who own the products they produce, and by individuals and groups. • the impact of production processes, personnel and technologies on the final product, including similarities anddifferences between media products in terms of when and where they are produced. Ownership and control • the effect of ownership and control of media organisations, including conglomerate ownership, diversification and vertical integration. Convergence • the impact of the increasingly convergent nature of media industries across different platforms and different national settings. Funding • the importance of different funding models, including government funded, not-for- profit and commercial models. Industries and audiences • how the media operate as commercial industries on a global scale and reach both large and specialised audiences. Media regulation • the functions and types of regulation of the media. • the challenges for media regulation presented by ‘new’ digital technologies. -

Children, Technology and Play

Research report Children, technology and play Marsh, J., Murris, K., Ng’ambi, D., Parry, R., Scott, F., Thomsen, B.S., Bishop, J., Bannister, C., Dixon, K., Giorza, T., Peers, J., Titus, S., Da Silva, H., Doyle, G., Driscoll, A., Hall, L., Hetherington, A., Krönke, M., Margary, T., Morris, A., Nutbrown, B., Rashid, S., Santos, J., Scholey, E., Souza, L., and Woodgate, A. (2020) Children, Technology and Play. Billund, Denmark: The LEGO Foundation. June 2020 ISBN: 978-87-999589-7-9 Table of contents Table of contents Section 1: Background to the study • 4 1.1 Introduction • 4 1.2 Aims, objectives and research questions • 4 1.3 Methodology • 5 Section 2: South African and UK survey findings • 8 2.1 Children, technology and play: South African survey data analysis • 8 2.2 Children, technology and play: UK survey data analysis • 35 2.3 Summary • 54 Section 3: Pen portraits of case study families and children • 56 3.1 South African case study family profiles • 57 3.2 UK case study family profiles • 72 3.3 Summary • 85 Section 4: Children’s digital play ecologies • 88 4.1 Digital play ecologies • 88 4.2 Relationality and children’s digital ecologies • 100 4.3 Children’s reflections on digital play • 104 4.4 Summary • 115 Section 5: Digital play and learning • 116 5.1 Subject knowledge and understanding • 116 5.2 Digital skills • 119 5.3 Holistic skills • 120 5.4 Digital play in the classroom • 139 5.5 Summary • 142 2 Table of contents Section 6: The five characteristics of learning through play • 144 6.1 Joy • 144 6.2 Actively engaging • 148 -

Internet of Toys: Julia and Lego Mindstorms

Internet of Toys: Julia and Lego Mindstorms Robin Deits December 13, 2015 Abstract The latest version of the Lego Mindstorms robotics system is an excel- lent candidate for the exploration of distributed robotics. I implemented bindings to the ev3dev operating system, which runs on the Mindstorms ev3 brick, in Julia. Using those bindings, I constructed a library to per- form a simple cooperative mapping task on a pair of mobile robots. Due to the hardware limitations of the ev3 processor, I was not yet able to run Julia onboard. Instead, I developed a simple server-client architec- ture using ZeroMQ [1] to allow Julia code to run off-board and control the Mindstorms robot over WiFi. With this system, I was able to map simple environments both in serial (with one robot) and in parallel (with a team of two robots). Contents 1 Background2 2 Hardware Interface3 2.1 Running Julia on the EV3...................3 2.2 Running Julia Off-board....................4 3 Software5 3.1 Low-Level Bindings.......................5 4 Collaborative Mapping on the EV36 4.1 Hardware Design........................6 4.2 Software Design.........................6 4.2.1 Finite-State Machine Behaviors............8 4.2.2 Mapping.........................8 4.2.3 Parallel Collaborative Mapping............9 5 Example Results9 5.1 Mapping.............................9 5.2 Software Performance.....................9 1 6 Future Work 12 6.1 Eliminating the WiFi Link................... 12 6.1.1 Move Julia onto the EV3............... 12 6.1.2 Mount a Raspberry Pi Onboard........... 12 6.1.3 Replace the EV3 entirely............... 13 6.1.4 Robot Operating System.............. -

Cult of Lego Sample

$39.95 ($41.95 CAN) The Cult of LEGO of Cult The ® The Cult of LEGO Shelve in: Popular Culture “We’re all members of the Cult of LEGO — the only “I defy you to read and admire this book and not want membership requirement is clicking two pieces of to doodle with some bricks by the time you’re done.” plastic together and wanting to click more. Now we — Gareth Branwyn, editor in chief, MAKE: Online have a book that justifi es our obsession.” — James Floyd Kelly, blogger for GeekDad.com and TheNXTStep.com “This fascinating look at the world of devoted LEGO fans deserves a place on the bookshelf of anyone “A crazy fun read, from cover to cover, this book who’s ever played with LEGO bricks.” deserves a special spot on the bookshelf of any self- — Chris Anderson, editor in chief, Wired respecting nerd.” — Jake McKee, former global community manager, the LEGO Group ® “An excellent book and a must-have for any LEGO LEGO is much more than just a toy — it’s a way of life. enthusiast out there. The pictures are awesome!” The Cult of LEGO takes you on a thrilling illustrated — Ulrik Pilegaard, author of Forbidden LEGO tour of the LEGO community and their creations. You’ll meet LEGO fans from all walks of life, like professional artist Nathan Sawaya, brick fi lmmaker David Pagano, the enigmatic Ego Leonard, and the many devoted John Baichtal is a contribu- AFOLs (adult fans of LEGO) who spend countless ® tor to MAKE magazine and hours building their masterpieces. -

Word Match Minds-On Investigations Hands-On Investigations

Minds-on investigations Word match Paper bridges: strong and stable or weak and wobbly? When using identical materials, one design can be weak and another can be strong. Find these vocabulary words from this poster in the word match. Then 1. Place a sheet of paper between two desktops. Lying flat, the paper will fall; it is not read through the Tampa Bay Times very strong or stable. or Orlando Sentinel to find these 2. Now roll the paper and tape it to form a tube. Place the paper between the two words in articles, headliners, ads, tables. By changing the shape, a stronger and more stable structure is created. or comics. 3. Fold the paper into different shapes and lay it across two desktops. Find the Tower Structure strongest and most stable design. Stable Shape Your skeleton: a natural frame structure Size Skeleton Each person has a natural frame structure inside his or her body — a skeleton! Our Flexible Rigid skeleton gives us shape and supports the weight of our muscles. The size of our frame, or skeleton, determines how tall we are. The tallest person who ever lived was Robert Pulley Lever Wadlow (1918-1940), of Alton, Ill. When he was five years old in kindergarten, he was 5 feet Machine Engineer 6 inches. He grew to be 8 feet 11 inches! Mechanical Gear I T G I E S J M T T H I U I W Y A M D K Compare shapes and sizes 1. Lie on the floor on butcher paper and ask a partner to trace the shape of your body.