Midamerica XL 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dangerous Summer

theHemingway newsletter Publication of The Hemingway Society | No. 73 | 2021 As the Pandemic Ends Yet the Wyoming/Montana Conference Remains Postponed Until Lynda M. Zwinger, editor 2022 the Hemingway Society of the Arizona Quarterly, as well as acquisitions editors Programs a Second Straight Aurora Bell (the University of Summer of Online Webinars.… South Carolina Press), James Only This Time They’re W. Long (LSU Press), and additional special guests. Designed to Confront the Friday, July 16, 1 p.m. Uncomfortable Questions. That’s EST: Teaching The Sun Also Rises, moderated by Juliet Why We’re Calling It: Conway We’ll kick off the literary discussions with a panel on Two classic posters from Hemingway’s teaching The Sun Also Rises, moderated dangerous summer suggest the spirit of ours: by recent University of Edinburgh A Dangerous the courage, skill, and grace necessary to Ph.D. alumna Juliet Conway, who has a confront the bull. (Courtesy: eBay) great piece on the novel in the current Summer Hemingway Review. Dig deep into n one of the most powerful passages has voted to offer a series of webinars four Hemingway’s Lost Generation classic. in his account of the 1959 bullfighting Fridays in a row in July and August. While Whether you’re preparing to teach it rivalry between matadors Antonio last summer’s Houseguest Hemingway or just want to revisit it with fellow IOrdóñez and Luis Miguel Dominguín, programming was a resounding success, aficionados, this session will review the Ernest Hemingway describes returning to organizers don’t want simply to repeat last publication history, reception, and major Pamplona and rediscovering the bravery year’s model. -

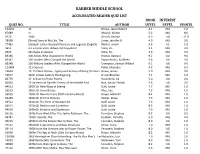

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

Jesse White Along with Illinois Poet Laureate Kevin Stein (Right) Present Andrew Galligan His Illi- Nois Emerging Writers Competition, Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Award

For more information about the Illinois Center for the Book and its programs, contact: The Illinois Center for the Book is a programming Illinois Center for the Book arm of the Illinois State Library that promotes Illinois State Library reading, writing and author programs with the Gwendolyn Brooks Building mission: “Nurturing and connecting readers and 300 S. Second St. An affiliate of the Center for the Book writers, and honoring our rich literary heritage.” Springfield, IL 62701 in the Library of Congress 217-558-2065 The Illinois Center for the Book was incorporated 217-782-1877 (fax) in 1985, making it the third affiliate of the Center Illinoiscenterforthebook.org for the Book in the Library of Congress. Today, ______________ all 50 states, the District of Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands have a center affiliated with the Li- Illinois authorsʼ names on the brary of Congress. Each state center provides pro- frieze of the Illinois State Library, grams that highlight their own literary heritage, books, reading, literacy and libraries. Gwendolyn Brooks Building Jane Addams, George Ade, Nelson Algren, Sherwood Anderson, Paul Angle, L. Frank Baum, Saul Bellow, Black Hawk, Ray Bradbury, Gwendolyn Brooks, Cyrus Colter, “Nurturing and connecting Theodore Dreiser, Finley Peter Dunne, Eliza Farnham, James T. Farrell, Edna Ferber, readers and writers, and honoring Henry Blake Fuller, Hamlin Garland, our rich literary heritage.” Lorraine Hansberry, Ben Hecht, Ernest Hemingway, Robert Herrick, James Jones, Ring Lardner, Abraham Lincoln, Vachel Lindsay, Edgar Lee Masters, William Maxwell, Frank Norris, Donald Culross Peattie, Elia Wilkinson Peattie, Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, Louis (Studs) Terkel, Richard Wright ILLINOIS EMERGING WRITERS COMPETITION Secretary of State and State Librarian Jesse White along with Illinois Poet Laureate Kevin Stein (right) present Andrew Galligan his Illi- nois Emerging Writers Competition, Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Award. -

White Privilege Topic of Discussion

FAN FAVORITE Faculty votes for requirement hike "Not everyone graduates with 128 credits, so there will be a small subset who need to pick The change would raise up one more class to graduate," said Yeterian. "There will be an even smaller subset who the graduation minimum need to pick up two classes." f rom120 to 128 credits The • majority of comparable institutions already require 128 credits to graduate, or the equivalent number of courses. Middlebury and By MATT APUZZO Bates, for instance, require 32 courses to gradu- EDITOR IN CHIEF ate. The credit requirement is more flexible than The faculty voted by a significant majority course requirements at other schools, as each at its November meeting to raise the gradua- semester with three courses must be offset by a tion requirement to 128 credits. The proposal semester with five courses. At Colby, because would raise the minimum from the current 120 classes are weighted differently, students can required for current students. elect five-credit courses while only taking three "This is something we needed to do to get classes a semester. At schools that require a us in line with our peer institutions," said Dean minimum number of courses, this is not possi- of the Faculty Edward Yeterian. ble. The change would take place for the class of One of the issues brought up last year was 2005, but requires approval from the Trustees how the change would effect Jan Plan intern- before it is implemented. ships. For each of the last two years, approxi- The proposal originated during ihe 1997-98 mately 360 students elected to do non-credit scholastic year but was not voted upon until course work during January. -

Joshua Salzmann, Ph.D. Associate Professor ▪ Department of History ▪ Northeastern Illinois University 5500 N

Joshua Salzmann, Ph.D. Associate Professor ▪ Department of History ▪ Northeastern Illinois University 5500 N. Saint Louis Ave. ▪ Chicago, IL 60625 773-442-5632 ▪ [email protected] EDUCATION University of Illinois at Chicago 2008 Ph.D., United States History University of Illinois at Chicago 2003 M.A., United States History Evergreen State College, Olympia, WA 2000 B.A., Liberal Arts ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor, Department of History, Northeastern Illinois University 2017-present Assistant Professor, Department of History, Northeastern Illinois University 2012-2017 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Illinois at Chicago 2010-2012 Lecturer, Department of History, University of Illinois at Chicago 2008-2009 PUBLICATIONS Book Liquid Capital: Making the Chicago Waterfront (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018). Winner of 2018 “Superior Achievement Award,” Illinois State Historical Society Honorable Mention in 2019 Jon Gjerde Prize competition, Midwest History Association Peer-Reviewed Articles and Book Chapters “Blood on the Tracks: Accidental Death and the Built Environment,” in City of Lake and Prairie: Chicago’s Environmental History, eds. William C. Barnett, Kathleen A. Brosnan, and Ann Durkin Keating (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020). “Bionic Ballplayers: Risk, Profit, and the Body as Commodity, 1964-2007,” (co-authored with Sarah Rose) LABOR: Studies in the Working-Class History of the Americas 11 (Spring 2014): 47-75. Winner of 2016 biennial “Best Article Prize,” Labor and Working Class History Association “The Creative Destruction of the Chicago River Harbor: Spatial and Environmental Dimensions of Industrial Capitalism, 1881-1909,” Enterprise and Society: The International Journal of Business History 13 (June 2012): 235-275. “The Lakefront’s Last Frontier: The Turnerian Mythology of Streeterville, 1886-1961,” The Journal of Illinois History 9 (Fall 2006): 201-214. -

Readers Guide 1.Indd

The Great Michigan READ 2007–08 Reader’s Guide “His eye ached and he was hungry. He kept on hiking, putting the miles of track back of him. .” —Ernest Hemingway, “The Battler,” The Nick Adams Stories “Nick looked back from the top of the hill by the schoolhouse. He saw the lights of WHAT IS The Great Michigan READ Petoskey and, off across Little Traverse Bay, the lights of Harbor Springs. .” “Ten Indians” Imagine everyone in Michigan reading the same book. At the same time. The Great Michigan Read is a community reading program for the entire state. With a statewide focus on a single literary masterpiece—Ernest Hemingway’s The Nick Adams Stories— it encourages Michiganians to read and rediscover literature. Why The Nick Adams Stories? The Nick Adams Stories is a literary masterpiece literally made in Michigan. The author, Ernest Hemingway, spent the majority of his fi rst 22 summers in Northern Michigan. These experiences played an essential role in his development as one of the world’s most signifi cant writers. What are The Nick Adams Stories about? The Nick Adams Stories chronicles a young man’s coming of age in a series of linked short stories. As Nick matures, he grapples with the complexities of adulthood, including war, death, marriage, and family. How can I participate? Get a copy of the book or audiobook at Meijer, Barnes & Noble, Borders, Schuler Books & Music, your local library, online, or through other retail locations. Read the book, utilize the reader’s guide and website, talk about it with your friends, family, or book club, and participate in Great Michigan Read events in your neighborhood. -

A. Booth Packing Company

MARINE SUBJECT FILE GREAT LAKES MARINE COLLECTION Milwaukee Public Library/Wisconsin Marine Historical Society page 1 Current as of January 7, 2019 A. Booth Packing Company -- see Booth Fleets Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987 (includes Antiquities Act of 1906) Abitibi Fleet -- see Abitibi Power and Paper Company Abitibi Power and Paper Company Acme Steamship Company Admiralty Law African Americans Aids to Navigation (Buoys) Aircraft, Sunken Alger Underwater Preserve -- see Underwater parks and preserves Algoma Central Railway Marine Algoma Steamship Co. -- see Algoma Central Railway (Marine Division) Algoma Steel Corporation Allan Line (Royal Mail Steamers) Allen & McClelland (shipbuilders) Allen Boat Shop American Barge Line American Merchant Marine Library Assn. American Shipbuilding Co. American Steamship Company American Steel Barge Company American Transport Lines American Transportation Company -- see Great Lakes Steamship Company, 1911-1957 Anchor Line Anchors Andrews & Sons (Shipbuilders) Andrie Inc. Ann Arbor (Railroad & Carferry Co.) Ann Arbor Railway System -- see Michigan Interstate Railway Company Antique Boat Museum Antiquities Act of 1906 see Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987 Apostle Islands -- see Islands -- Great Lakes Aquamarine Armada Lines Arnold Transit Company Arrivals & Departures Association for Great Lakes Maritime History Association of Lake Lines (ALL) Babcock & Wilcox Baltic Shipping Co. George Barber (Shipbuilder) Barges Barry Transportation Company Barry Tug Line -- see Barry Transportation Company Bassett Steamship Company MARINE SUBJECT FILE GREAT LAKES MARINE COLLECTION Milwaukee Public Library/Wisconsin Marine Historical Society page 2 Bay City Boats Inc. Bay Line -- see Tree Line Navigation Company Bay Shipbuilding Corp. Bayfield Maritime Museum Beaupre, Dennis & Peter (Shipbuilders) Beaver Island Boat Company Beaver Steamship Company -- see Oakes Fleets Becker Fleet Becker, Frank, Towing Company Bedore’s, Joe, Hotel Ben Line Bessemer Steamship Co. -

Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame 2001

CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME 2001 City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Richard M. Daley Clarence N. Wood Mayor Chair/Commissioner Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues William W. Greaves Laura A. Rissover Director/Community Liaison Chairperson Ó 2001 Hall of Fame Committee. All rights reserved. COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues 740 North Sedgwick Street, 3rd Floor Chicago, Illinois 60610 312.744.7911 (VOICE) 312.744.1088 (CTT/TDD) Www.GLHallofFame.org 1 2 3 CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME The Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and our country are made aware of the contributions of Chicago's lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate homophobic bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. The Hall of Fame recognizes the volunteer and professional achievements of people of the LGBT communities, their organizations, and their friends, as well as their contributions to their communities and to the city of Chicago. This is a unique tribute to dedicated individuals and organizations whose services have improved the quality of life for all of Chicago's citizens. -

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

In 193X, Constance Rourke's Book American Humor Was Reviewed In

OUR LIVELY ARTS: AMERICAN CULTURE AS THEATRICAL CULTURE, 1922-1931 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Schlueter, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Thomas Postlewait, Adviser Professor Lesley Ferris Adviser Associate Professor Alan Woods Graduate Program in Theatre Copyright by Jennifer Schlueter c. 2007 ABSTRACT In the first decades of the twentieth century, critics like H.L. Mencken and Van Wyck Brooks vociferously expounded a deep and profound disenchantment with American art and culture. At a time when American popular entertainments were expanding exponentially, and at a time when European high modernism was in full flower, American culture appeared to these critics to be at best a quagmire of philistinism and at worst an oxymoron. Today there is still general agreement that American arts “came of age” or “arrived” in the 1920s, thanks in part to this flogging criticism, but also because of the powerful influence of European modernism. Yet, this assessment was not, at the time, unanimous, and its conclusions should not, I argue, be taken as foregone. In this dissertation, I present crucial case studies of Constance Rourke (1885-1941) and Gilbert Seldes (1893-1970), two astute but understudied cultural critics who saw the same popular culture denigrated by Brooks or Mencken as vibrant evidence of exactly the modern American culture they were seeking. In their writings of the 1920s and 1930s, Rourke and Seldes argued that our “lively arts” (Seldes’ formulation) of performance—vaudeville, minstrelsy, burlesque, jazz, radio, and film—contained both the roots of our own unique culture as well as the seeds of a burgeoning modernism. -

Ernest Hemingway's Mistresses and Wives

Ernest Hemingway’s Mistresses and Wives: Exploring Their Impact on His Female Characters by Stephen E. Henrichon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph. D. Lawrence R. Broer, Ph. D. Victor Peppard, Ph. D. Date of Approval: October 28, 2010 Keywords: Up in Michigan, Cat in the Rain, Canary for One, Francis Macomber, Kilimanjaro, White Elephants, Nobody Ever Dies, Seeing-Eyed Dog © Copyright 2010, Stephen E. Henrichon TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ i CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2: MICHIGAN: WHERE IT ALL BEGAN ....................................................9 CHAPTER 3: ADULTERY, SEPARATION AND DIVORCE ......................................16 CHAPTER 4: AFRICA ....................................................................................................29 CHAPTER 5: THE WAR YEARS AND BEYOND........................................................39 CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSION .........................................................................................47 CHAPTER 7: REFERENCES ..........................................................................................52 i ABSTRACT “Conflicted” succinctly describes Ernest Hemingway. He had a strong desire