Charles Vance – Interview Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philip Wilson Director

Philip Wilson Director Philip is a freelance director who spent four very successful years as the Artistic Director of Salisbury Playhouse (2007-2011). He trained on the Regional Theatre Young Director Scheme (Greenwich Theatre, 1995-96), and in 2015 was awarded the inaugural David Fraser/Andrea Wonfor bursary, to train as a multi- camera television director. Recent projects include the British Premiere of Ken Ludwig’s A Fox on the Fairway at Queen’s Theatre Hornchurch and Terence Rattigan’s After The Dance at Theatre By The Lake in Keswick. His adaptations of Philip Pullman’s Grimm Tales (first produced in an immersive staging at Shoreditch Town Hall and then the Oxo Bargehouse, in 2014 and 2015) were performed at Chichester this summer. Philip’s book, Dramatic Adventures in Rhetoric, co-written with Giles Taylor, is published by Oberon Books, and Grimm Tales is available from Nick Hern Books. Agents Giles Smart Assistant Ellie Byrne [email protected] +44 (020 3214 0812 Credits Theatre Production Company Notes THE BOY WITH THE The Hope Theatre By John Straiton BEE JAR 2021 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes COCKPIT LAMDA By Bridget Boland 2021 THE LIGHTS LAMDA By Howard Korder 2019 THIS ISLAND'S MINE Ardent Theatre By Philip Osment 2019 Company / King's Head Theatre PHILIP PULLMAN'S Unicorn Theatre Adapted for the stage by Philip Wilson GRIMM TALES Directed by Kirsty Housley 2018 STRANGE LAMDA By Rodney Ackland ORCHESTRA Performed in The Sainsbury Theatre 2018 PERFECT NONSENSE Theatre By The Lake From the works of P.G. -

3. Terence Rattigan- First Success and After

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „In and out of the limelight- Terence Rattigan revisited“ Verfasserin Covi Corinna angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 30. Jänner 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: 343 Diplomstudium Anglistik und Amerikanistik UniStG Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Rudolf Weiss Table of contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………....p.4 2. The History of the Well-Made Play…………………………......p.5 A) French Precursors.....................................................................p.6 B) The British Well-Made Play...................................................p.10 a) Tom Robertson and the 1870s...........................................................p.10 b) The “Renaissance of British Drama”...............................................p.11 i. Arthur Wing Pinero (1855-1934) and Henry Arthur Jones (1851- 1929)- The precursors of the “New Drama”..............................p.12 ii. Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)..............................................................p.15 c) 1900- 1930 “The Triumph of the New Drama”...............................p.17 i. Harley Granville-Barker (1877-1946)………………................p.18 ii. William Somerset Maugham (1874-1965)..................................p.18 iii. Noel Coward (1899-1973)............................................................p.20 3. Terence Rattigan- first success and after...................................p.21 A) French Without Tears (1936)...................................................p.22 -

Sir Terence Rattigan, CBE 1911 – 1977

A Centenary Service of Celebration for the Life and Work of Sir Terence Rattigan, CBE 1911 – 1977 “God from afar looks graciously upon a gentle master.” St Paul’s Covent Garden Tuesday 22nd May 2012 11.00am Order of Service PRELUDE ‘O Soave Fanciulla’ from La Bohème by G. Puccini Organist: Simon Gutteridge THE WELCOME The Reverend Simon Grigg The Lord’s Prayer Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. For thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory, for ever and ever. Amen. TRIBUTE DAVID SUCHET, CBE written by Geoffrey Wansell 1 ARIA ‘O Mio Babbino Caro’ from Gianni Schicchi by G. Puccini CHARLOTTE PAGE HYMN And did those feet in ancient time Walk upon England's mountains green? And was the holy Lamb of God On England's pleasant pastures seen? And did the countenance divine Shine forth upon our clouded hills? And was Jerusalem builded here Among those dark satanic mills? Bring me my bow of burning gold! Bring me my arrows of desire! Bring me my spear! O clouds, unfold! Bring me my chariot of fire! I will not cease from mental fight, Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand, Till we have built Jerusalem In England's green and pleasant land. ADDRESS ‘The Final Test’ SIR RONALD HARWOOD, CBE 2 HYMN I vow to thee, my country, all earthly things above, Entire and whole and perfect, the service of my love: The love that asks no question, the love that stands the test, That lays upon the altar the dearest and the best; The love that never falters, the love that pays the price, The love that makes undaunted the final sacrifice. -

The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan

Director Sarah Esdaile Designer Ruari Murchison Lighting Designer Chris Davey Sound Designer Mic Pool Composer Simon Slater Casting Director Siobhan Bracke Voice Charmian Hoare Cast Ross Armstrong, Sam Cox, John Hollingworth, Maxine Peake, Ann Penfold John Ramm, Lex Shrapnel, Eleanor Wyld 18 February to 12 March By Terence Rattigan Teacher Resource Pack Introduction Welcome to the Resource Pack for West Yorkshire Playhouse’s production of The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan. In the pack you will find a host of information sheets to enhance your visit to the show and to aid your students’ exploration of this classic text. Contents: Page 2 Synopsis Pages 3 Terence Rattigan Timeline Page 5 The Rehearsal Process Page 10 Interview with Sarah Esdaile, Director and Maxine Peake, Hester Page 12 Interview with Suzi Cubbage, Production Manager Page 14 The Design The Deep Blue Sea By Terence Rattigan, Directed by Sarah Esdaile, Designed Ruari Murchison Hester left her husband for another man. Left the security of the well respected judge, for wild, unpredictable, sexy Freddie – an ex-fighter pilot. Now she’s reached the end of the line. Freddie’s raffish charm has worn thin and Hester is forced to face the reality of life with a man who doesn’t want to be with her. The simple act of a forgotten birthday pushes her to desperation point and to facing a future that offers no easy resolutions. Rattigan’s reputation was founded on his mastery of the ‘well made play’. Now, one hundred years after his birth, it is his skilful creation of troubled, emotional characters that has brought audiences and critics alike to re-visit his plays with renewed appreciation. -

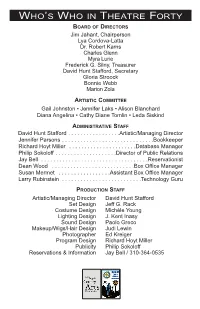

DIRECTED by JULES AARON PRODUCED by DAVID HUNT STAFFORD Set Designer

WHO’S WHO IN THEATRE FORTY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Jim Jahant, Chairperson Lya Cordova-Latta Dr. Robert Karns Charles Glenn Myra Lurie Frederick G. Silny, Treasurer David Hunt Stafford, Secretary Gloria Stroock Bonnie Webb Marion Zola ARTISTIC COMMITTEE Gail Johnston • Jennifer Laks • Alison Blanchard Diana Angelina • Cathy Diane Tomlin • Leda Siskind ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF David Hunt Stafford . .Artistic/Managing Director Jennifer Parsons . .Bookkeeper Richard Hoyt Miller . .Database Manager Philip Sokoloff . .Director of Public Relations Jay Bell . .Reservationist Dean Wood . .Box Office Manager Susan Mermet . .Assistant Box Office Manager Larry Rubinstein . .Technology Guru PRODUCTION STAFF Artistic/Managing Director David Hunt Stafford Set Design Jeff G. Rack Costume Design Michèle Young Lighting Design J. Kent Inasy Sound Design Paolo Greco Makeup/Wigs/Hair Desi gn Judi Lewin Photographer Ed Kreiger Program Design Richard Hoyt Miller Publicity Philip Sokoloff Reservations & Information Jay Bell / 310-364-0535 THEATRE FORTY PRESENTS The 6th Production of the 2016-2017 Season SeparateSeparate TablesTables BY TERENCE RATTIGAN DIRECTED BY JULES AARON PRODUCED BY DAVID HUNT STAFFORD Set Designer..............................................JEFF G. RACK Costume Designer................................MICHÈLE YOUNG Lighting Designer....................................J. KENT INASY Sound Designer ........................................PAOLO GRECO Makeup/Wigs/Hair Designer.....................JUDI LEWIN Stage Manager.........................................DON SOLOSAN Assistant Stage Manager ..................RICHARD CARNER Assistant Director.................................JORDAN HOXSIE PRODUCTION NOTES "Loneliness is a terrible thing, don't you agree." "Yes I do agree. A terrible thing." -- Separate Tables SPECIAL THANKS Theatre 40 would like to thank the BHUSD Board of Education and BH High School administration for their assistance and support in making Theatre 40’s season possible. Thanks to… HOWARD GOLDSTEIN LISA KORBATOV NOAH MARGO MEL SPITZ ISABEL HACKER DR. -

The Rattigan the Newsletter of the Terence Rattigan Society ISSUE NO

The Rattigan The Newsletter of The Terence Rattigan Society ISSUE NO. 13 DECEMBER 2014 Version Posing for a passer-by in theatreland Clive Montellier reports on a visit to the V&A Archive Collection Photos by John Ruddy This year’s AGM took place in the sleek and elegant was swiftly approved; then almost before we knew it, surroundings of Sheekey’s famous fish restaurant just off your Committee had been re-elected and were later to St Martin’s Lane. This enabled members to carouse in an be found posing in the street as a gallant passerby took a appropriately well-behaved manner whilst being served picture to mark the occasion. Also, centre, were honor- a special Sunday lunch by a waiting staff who swished ary founder member Adrian Brown, new honorary silently around like extras from the set of Hello Dolly! It member Judy Buxton (see p 2) and her husband, the also expedited the business of the day, which had all the thoroughly delightful Jeffrey Holland. In her speech, appearance of two rather agreeable post-prandial Barbara Longford announced the decision to organise a speeches by our Chairman and our Secretary with an TR Society award for a new play, of which there will be occasional raising of hands. I’m sure we were all paying fuller details in due course next year. With the Oxford rapt attention, and the proposal to seek charitable status Conference and other events, all bodes well for 2015. SOCIETY AGM AT SHEEKEY’S RESTAURANT, P 1 TWO NEW RATTIGAN EPISODES, PP 4, 5 INTRODUCING JUDY BUXTON, PP 2, 8 RANDOM AGM THOUGHTS PP 6, 7 -

Guide to the Presbyterian Players Collection

Guide to IU South Bend Presbyterian Players Collection Summary Information Repository: Indiana University South Bend Archives 1700 Mishawaka Avenue P.O. Box 7111 South Bend, Indiana 46634 Phone: (574) 520-4392 Email: [email protected] Creator: Indiana University South Bend Title: Presbyterian Players Collection Extent: .50 linear ft. Abstract: Often touted as “South Bend’s oldest community theatre,” the Presbyterian Players mounted hundreds of productions over five decades, including familiar plays and popular musicals, as well as the occasional lesser-known work. The group formed in 19451 under the auspices of the First Presbyterian Church of South Bend, Indiana. While some productions took place in venues like the Washington High School Auditorium, the Indiana University South Bend Auditorium, or the Bendix Theatre at the Century Center, the majority of the performances associated with the programs in this collection took place in the Church itself. The First Presbyterian Church has a long history as part of the wider Michiana community. A small group of early South Bend residents came together to form the church in 1834, and as the congregation grew, so too did the structures built to accommodate it. The grandest of these, built in 1889, still stand at the corner of Lafayette and West Washington Streets—though it is no longer the site of the First Presbyterian Church, which has been located on West Colfax Avenue since 1953.2 Sisters Mary Pappas (February 7, 1926–June 11, 2012) and Aphrodite Pappas (c. 1923– ), who donated the materials found in this inventory, directed, acted in, or otherwise helped stage numerous performances of the Presbyterian Players. -

Rattigan Version 33 – Jul 2020

The Rattigan The Newsletter of The Terence Rattigan Society ISSUE NO. 33 JULY 2020 Version When the show doesn’t go on his will always be remembered as the year of generally held good. Until now. the lockdown, as no one will need reminding. Well, public health does have to come first. And T It has pulled the rug from under people’s lives governments do have to make very tough decisions. It in an extraordinary and devastating fashion. And the is not the business of this newsletter to take this, or world of theatre and performance arts has suffered any, government to task, nor to criticise (or praise) perhaps its deadliest blow since the Puritans closed all the way this crisis has been handled, but it is the theatres and places of business of this news- entertainment in the letter to observe that mid-17th century. somehow theatre ‘will As The Stage news- always out’ in one way paper reminded us or another, even in recently, the govern- the most adverse ment ordered no circumstances. closures during the First A perfect example World War, and perfor- of this is the rehearsed mances continued reading produced by during Zeppelin raids. Jermyn Street Theatre Similarly, there were on 26 May of one of no such closures during A screenshot from the online rehearsed reading of In Praise of Rattigan’s later plays, Love streamed by Jermyn Street Theatre via YouTube on 26 the Spanish ’Flu May, featuring Jack Klaff, Issy van Randwyck, Andrew Francis In Praise of Love. The epidemic of 1918-19 (all pictured) and Mackenzie Heynes, directed by Cat Robey. -

CM1 STD Format.Pdf

1 Ahoy hoy! Hello and welcome to the new, re-launched Cosmic Masque! We hope you'll stay with us as I couldn't be more thrilled to be back in an editor’s we try to bring you a wide range of material from chair with the honoured privilege of resurrecting a the extended worlds of Doctor Who and Doctor DWAS classic and I couldn't be happier to have Who fandom. my friend, Ian Wheeler, alongside me for the ride too. We are both stupidly excited about this pro- It's been around a long time, this Society of ject. The amount of emails sent between us ex- our's. For nearly forty years, DWAS has been pressing this is similar to those of a couple teen- putting on events, publishing fanzines and bring- age boys preparing for a double date. So here ing fans together. For most of this time, Celestial we both are, dressed in our Sunday best with the Toyroom has been our flagship publication but promise of a kebab at the end of the night, it's now it's time for its sister title to make a trium- going to be fun and a little bit mad! phant return. This issue has been a challenging one to put together but we hope you approve of Welcome to first issue of the returning Cosmic the finished result. Masque, how exciting! Some of you may recall we tested the water with a downloadable CM for My own contribution to DWAS spans nearly the Fiftieth Anniversary of Who which I am thirty years as a member and twenty-five as an pleased to say was very well received. -

Past Productions 1976 • Sound of Murder • Ladies in Retirement 1977

Past productions 1976 • Sound of murder • Ladies in Retirement 1977 • Move Over Mrs Markham • The Owl and the Pussy-cat went to Sea • Relatively Speaking • Witness for the Prosecution • Our Town 1978 • Flibberty and the Penguin • Blithe Spirit • A Midsummer Night's Dream • Three One-act plays • Hay Fever • Sweeney Todd 1979 • Pied Piper • Everything in the Garden • When We Are Married • Trap for a Lonely Man • A Month in the Country • Waltz of the Toreadors 1980 • Goldilocks and the Three Bears • How the Other Half Loves • Ghost Train • Letter from the General • Good Woman of Setzuan • Busybody 1981 • The Plotters of Cabbage Patch Corner • The Caretaker • Arms and the Man • Double Bill • This Year Next Year • Who Killed Santa Claus 1982 • The Incredible Vanishing • Post Horn Gallop • Winter’s Tale • Bedroom Farce • Anybody for Tennis 1983 • Quest for the Golden Key • Hobson's Choice • The Miser • The Potting Shed • Anastasia • Not Now Darling 1984 • Pinocchio • A Lily in Little India • The Importance of being Earnest(1) • Any Number Can Die • House Guest • Noah 1985 • The Gingerbread Man • A Life • An Italian Straw Hat • The Deep Blue Sea • Lloyd George knew my Father • Under Milk Wood 1986 • The Man in the Moon • The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie • Time and Time Again • A Nightingale Sang • A Dolls House • All in Good Time 1987 • The Singing Swans • Arsenic and Old Lace • I Have Been Here Before • The Lady's not for Burning • Flare Path • A Little Hotel on the Side 1988 • Mr Macaroni • Love on the Dole • The Drunkard • Laughter and Song -

IN PRAISE of LOVE by Terence Rattigan

PRESS RELEASE – Wednesday 19 September 2018 IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED here Twitter/ Facebook / website Theatre Royal Bath Productions presents IN PRAISE OF LOVE by Terence Rattigan ▪ FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED FOR TERENCE RATTIGAN’S IN PRAISE OF LOVE WITH CHRISTOPHER BONWELL AND JULIAN WADHAM JOINING ROBERT LINDSAY AND TARA FITZGERALD ▪ JONATHAN CHURCH MAKES HIS USTINOV STUDIO DIRECTORIAL DEBUT IN THE FINAL PRODUCTION OF THEATRE ROYAL BATH’S 2018 SUMMER SEASON ▪ RUNNING FROM 3 OCTOBER TO 3 NOVEMBER, WITH OPENING NIGHT ON 15 OCTOBER ▪ IMAGES AVAILABLE TO DOWNLOAD HERE Theatre Royal Bath Productions today announces full casting for In Praise of Love at the Ustinov Studio with Christopher Bonwell and Julian Wadham joining the previously announced Robert Lindsay and Tara Fitzgerald. Jonathan Church will direct Terence Rattigan’s powerful drama at the Ustinov Studio marking his first production at the venue as well as the closing play in his second year as Artistic Director of Theatre Royal Bath’s Summer Season. In Praise of Love will run from Wednesday 3 October to Saturday 3 November with opening night or press on Monday 15 October. In Praise of Love is a perceptive and compelling drama about the concealed truths and veiled emotions in a marriage. Sebastian and Lydia Crutwell live in a small flat in Islington. Sebastian, once a promising novelist, is now a cantankerous critic. Lydia, an Estonian refugee, has recently discovered she is seriously ill, news that she confides to a family, Mark, but not to Sebastian. Over the course of two evenings, a series of heart-breaking revelations changes the facade of Lydia and Sebastian’s relationship forever. -

2021 Annual STD Format.Pdf

1 Pat was charming and spent a lot Editorial of time with the fans afterwards. He signed my little autograph By Paul Winter book ‘To Paul. Pat Troughton’ and I still treasure it to this day. I am one of those fans lucky A year later he was gone, but of enough to have met Patrick course, was never forgotten. Troughton, albeit only briefly. When I was seventeen years old Thank you Doctor. the DWAS annual convention ‘Panopticon’ came to Brighton and I realised that with the town (as it Paul then was) within bus journey dis- tance, I could actually attend. And so for two days in 1985 I im- mersed myself into the world of Doctor Who, at Brighton’s Metropole Hotel on the seafront. THE CELESTIAL TOYROOM ANNUAL 2021 Now, I know of the tremendous angst that event caused behind the scenes, causing the Society Published by The Doctor Who Ap- some financial problems, that in preciation Society. All content is © turn led to other problems and so DWAS and to the respective con- on. However, my enduring memo- tributors. ries are of seeing (and meeting) Jon Pertwee, and making his only full UK convention appearance, CONTACT US Patrick Troughton. Pat appeared on the Saturday and took the DWAS stage with Michael Craze who P O Box 1011 was interviewed first. When the Horsham time came for the man himself to RH12 9RZ, UK appear the room was buzzing with excitement. Instead of coming on- Edited by: Paul Winter to the stage from the side as other Publications Manager: Rik Moran guests had done, Pat instead en- tered the hall from the back.