Media Diversity in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music on PBS: a History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station

Music on PBS: A History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station Rochelle Lade (BArts Monash, MArts RMIT) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2021 Abstract This historical case study explores the programs broadcast by Melbourne community radio station PBS from 1979 to 2019 and the way programming decisions were made. PBS has always been an unplaylisted, specialist music station. Decisions about what music is played are made by individual program announcers according to their own tastes, not through algorithms or by applying audience research, music sales rankings or other formal quantitative methods. These decisions are also shaped by the station’s status as a licenced community radio broadcaster. This licence category requires community access and participation in the station’s operations. Data was gathered from archives, in‐depth interviews and a quantitative analysis of programs broadcast over the four decades since PBS was founded in 1976. Based on a Bourdieusian approach to the field, a range of cultural intermediaries are identified. These are people who made and influenced programming decisions, including announcers, program managers, station managers, Board members and the programming committee. Being progressive requires change. This research has found an inherent tension between the station’s values of cooperative decision‐making and the broadcasting of progressive music. Knowledge in the fields of community radio and music is advanced by exploring how cultural intermediaries at PBS made decisions to realise eth station’s goals of community access and participation. ii Acknowledgements To my supervisors, Jock Given and Ellie Rennie, and in the early phase of this research Aneta Podkalicka, I am extremely grateful to have been given your knowledge, wisdom and support. -

Chapter 3: the State of the Community Broadcasting Sector

3 The state of the community broadcasting sector 3.1 This chapter discusses the value of the community broadcasting sector to Australian media. In particular, the chapter outlines recent studies demonstrating the importance of the sector. 3.2 The chapter includes an examination of the sector’s ethos and an outline of the services provided by community broadcasters. More detail is provided on the three categories of broadcaster identified as having special needs or cultural sensitivities. 3.3 The chapter also discusses the sector’s contribution to the economy, and the importance of the community broadcasting sector as a training ground for the wider media industry including the national and commercial broadcasters. Recent studies 3.4 A considerable amount of research and survey work has been conducted to establish the significance of the community broadcasting sector is in Australia’s broader media sector. 3.5 Several comprehensive studies of the community broadcasting sector have been completed in recent years. The studies are: Culture Commitment Community – The Australian Community Radio Sector Survey Of The Community Radio Broadcasting Sector 2002-03 62 TUNING IN TO COMMUNITY BROADCASTING Community Broadcast Database: Survey Of The Community Radio Sector 2003-04 Financial Period Community Radio National Listener Surveys (2004 and 2006) Community Media Matters: An Audience Study Of The Australian Community Broadcasting Sector. 3.6 Each of these studies and their findings is described below. Culture Commitment Community – The Australian Community Radio Sector1 3.7 This study was conducted between 1999 and 2001, by Susan Forde, Michael Meadows, Kerrie Foxwell from Griffith University. 3.8 CBF discussed the research: This seminal work studies the current issues, structure and value of the community radio sector from the perspective of those working within it as volunteers and staff. -

Public Hearings in Melbourne and Alice Springs – 20-21 July Tuning Into Community Broadcasting

MEDIA ALERT Issued: 18 July 2006 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Chair – Jackie Kelly MP STANDING COMMITTEE ON COMMUNICATIONS, Deputy – Julie Owens MP INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND THE ARTS Public hearings in Melbourne and Alice Springs – 20-21 July Tuning into community broadcasting The key role that community radio and television broadcasting plays for ethnic, indigenous, vision impaired and regional areas will be discussed during public hearings held in Melbourne (20 July) and Alice Springs (21 July). These are the second hearings for the inquiry into community broadcasting being conducted by the Standing Committee on Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. In Melbourne, the Committee will hear from Channel 31 (C31), which is a not-for-profit television service providing locally-based entertainment, education and information targeting the many diverse communities within Victoria. A number of radio broadcasters will also appear to outline the vital services they provide to communities. Vision Australia operates a network of radio for the print handicapped stations in Victoria and southern NSW. The National Ethnic and Multicultural Broadcasters’ Council is the peak body representing ethnic broadcasters in Australia, and 3ZZZ is Melbourne’s key ethnic community broadcaster. Western Radio Broadcasters operates Stereo 974 FM in Melbourne’s western suburbs and 3KND is Victoria’s only indigenous community broadcaster. In Alice Springs, the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association operates 8KIN FM, and also a recording studio and television production company. PY Media and the Top End Aboriginal Bush Broadcasting Association assist local and Indigenous groups to develop information services in remote communities. Radio 8CCC is a general community radio station broadcasting to Alice Springs and Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory. -

Tuning in to Community Broadcasting

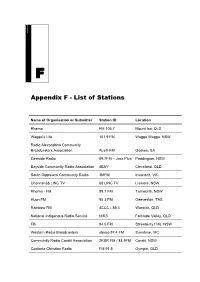

F Appendix F - List of Stations Name of Organisation or Submitter Station ID Location Rhema FM 105.7 Mount Isa, QLD Wagga’s Life 101.9 FM Wagga Wagga, NSW Radio Alexandrina Community Broadcasters Association ALeX-FM Goolwa, SA Eastside Radio 89.7FM – Jazz Plus Paddington, NSW Bayside Community Radio Association 4BAY Cleveland, QLD South Gippsland Community Radio 3MFM Inverloch, VIC Channel 68 LINC TV 68 LINC TV Lismore, NSW Rhema - FM 89.7 FM Tamworth, NSW Huon FM 95.3 FM Geeveston, TAS Rainbow FM 4CCC - 89.3 Warwick, QLD National Indigenous Radio Service NIRS Fortitude Valley, QLD FBi 94.5 FM Strawberry Hills, NSW Western Radio Broadcasters stereo 97.4 FM Sunshine, VIC Community Radio Coraki Association 2RBR FM / 88.9FM Coraki, NSW Cooloola Christian Radio FM 91.5 Gympie, QLD 180 TUNING IN TO COMMUNITY BROADCASTING Orange Community Broadcasting FM 107.5 Orange, NSW 3CR - Community Radio 3CR Collingwood, VIC Radio Northern Beaches 88.7 & 90.3 FM Belrose, NSW ArtSound FM 92.7 Curtin, ACT Radio East 90.7 & 105.5 FM Lakes Entrance, VIC Great Ocean Radio -3 Way FM 103.7 Warrnambool, VIC Wyong-Gosford Progressive Community Radio PCR FM Gosford, NSW Whyalla FM Public Broadcasting Association 5YYY FM Whyalla, SA Access TV 31 TV C31 Cloverdale, WA Family Radio Limited 96.5 FM Milton BC, QLD Wagga Wagga Community Media 2AAA FM 107.1 Wagga Wagga, NSW Bay and Basin FM 92.7 Sanctuary Point, NSW 96.5 Spirit FM 96.5 FM Victor Harbour, SA NOVACAST - Hunter Community Television HCTV Carrington, NSW Upper Goulbourn Community Radio UGFM Alexandra, VIC -

THE PACIFIC-ASIAN LOG January 2019 Introduction Copyright Notice Copyright 2001-2019 by Bruce Portzer

THE PACIFIC-ASIAN LOG January 2019 Introduction Copyright Notice Copyright 2001-2019 by Bruce Portzer. All rights reserved. This log may First issued in August 2001, The PAL lists all known medium wave not reproduced or redistributed in whole or in part in any form, except with broadcasting stations in southern and eastern Asia and the Pacific. It the expressed permission of the author. Contents may be used freely in covers an area extending as far west as Afghanistan and as far east as non-commercial publications and for personal use. Some of the material in Alaska, or roughly one half of the earth's surface! It now lists over 4000 this log was obtained from copyrighted sources and may require special stations in 60 countries, with frequencies, call signs, locations, power, clearance for anything other than personal use. networks, schedules, languages, formats, networks and other information. The log also includes longwave broadcasters, as well as medium wave beacons and weather stations in the region. Acknowledgements Since early 2005, there have been two versions of the Log: a downloadable pdf version and an interactive on-line version. My sources of information include DX publications, DX Clubs, E-bulletins, e- mail groups, web sites, and reports from individuals. Major online sources The pdf version is updated a few a year and is available at no cost. There include Arctic Radio Club, Australian Radio DX Club (ARDXC), British DX are two listings in the log, one sorted by frequency and the other by country. Club (BDXC), various Facebook pages, Global Tuners and KiwiSDR receivers, Hard Core DXing (HCDX), International Radio Club of America The on-line version is updated more often and allows the user to search by (IRCA), Medium Wave Circle (MWC), mediumwave.info (Ydun Ritz), New frequency, country, location, or station. -

Speak! the Community Listens

Speak! The Community Listens ABC Radio, Nova and Triple J are all household radio names. Between AM and FM core radio stations, we get our international and national news, entertainment and music. But for those of us who want something a bit closer to home, or something slightly out of the mainstream, there is community radio. Community radio first made its appearance in 1972, following the election of Gough Whitlam, whose government believed in developing grass-root social participation (Seneviratne 1993, pg. 4). In 1993, there were just 118 community radio services across Australia, with 2.5 million people tuning in each week (Seneviratne 1993, pg. 5). Now, Community broadcasting is Australia’s largest media sector, with over 5 million people tuning into over 440 radio services each week (Community Broadcasting Association of Australia 2017). Community radio has been a major avenue for individuals to voice their opinions and experiences to a broader community. Even though community radio, due to its limited funding, is mainly staffed by volunteers, many of the community radio broadcasters have professional experience. The Australian community broadcasting sector is also recognised internationally as a successful form of grassroots media (Community Broadcasting Foundation 2017). As such, community radio should be considered in a professional light. Earlier this year, a brave 14 year old radio host, Lilly Lyons, made headlines when she used community radio to reach out to other sexual assault survivors (Costello 2017). She described the radio as ‘helping her get her voice out there’, a voice that continues to inspire other survivors, reminding them that they are not alone. -

Call Sign Station Name 1RPH Radio 1RPH 2AAA 2AAA 2ARM Armidale

Call Sign Station Name 1RPH Radio 1RPH 2AAA 2AAA 2ARM Armidale Community Radio - 2ARM FM92.1 2BBB 2BBB FM 2BLU RBM FM - 89.1 Radio Blue Mountains 2BOB 2BOB RADIO 2CBA Hope 103.2 2CCC Coast FM 96.3 2CCR Alive905 2CHY CHYFM 104.1 2DRY 2DRY FM 2EAR Eurobodalla Radio 107.5 2GCR FM 103.3 2GLA Great Lakes FM 2GLF 89.3 FM 2GLF 2HAY 2HAY FM 92.1 Cobar Community Radio Incorporated 2HOT FM 2KRR KRR 98.7 2LVR 97.9 Valley FM 2MBS Fine Music 102.5 2MCE 2MCE 2MIA The Local One 95.1 FM 2MWM Radio Northern Beaches 2NBC 2NBC 90.1FM 2NCR River FM - 92.9 2NSB FM 99.3 - 2NSB 2NUR 2NURFM 103.7 2NVR Nambucca Valley Radio 2OCB Orange FM 107.5 2OOO 2TripleO FM 2RDJ 2RDJ FM 2REM 2REM 107.3FM 2RES 89.7 Eastside Radio 2RPH 2RPH - Sydney's Radio Reading Service 2RRR 2RRR 2RSR Radio Skid Row 2SER 2SER 2SSR 2SSR 99.7 FM 2TEN TEN FM TLC 100.3FM TLC 100.3 FM 2UUU Triple U FM 2VOX VOX FM 2VTR Hawkesbury Radio 2WAY 2WAY 103.9 FM 2WEB Outback Radio 2WEB 2WKT Highland FM 107.1 1XXR 2 Double X 2YOU 88.9 FM 3BBB 99.9 Voice FM 3BGR Good News Radio 3CR 3CR 3ECB Radio Eastern FM 98.1 3GCR Gippsland FM 3GRR Radio EMFM 3HCR 3HCR - High Country Radio 3HOT HOT FM 3INR 96.5 Inner FM 3MBR 3MBR FM Mallee Border Radio 3MBS 3MBS 3MCR Radio Mansfield 3MDR 3MDR 3MFM 3MFM South Gippsland 3MGB 3MGB 3MPH Vision Australia Radio Mildura 107.5 3NOW North West FM 3ONE OneFM 98.5 3PBS PBS - 3PBS 3PVR Plenty Valley FM 88.6 3REG REG-FM 3RIM 979 FM 3RPC 3RPC FM 3RPH Vision Australia 3RPH 3RPP RPP FM 3RRR Triple R (3RRR) 3SCB 88.3 Southern FM 3SER Casey Radio 3UGE UGFM - Radio Murrindindi 3VYV Yarra -

Agenda of Council Meeting

Contents AGENDA Council Meeting to be held at Darebin Civic Centre, 350 High Street Preston on Monday, 7 August 2017 at 6.00 pm. Public question time will commence shortly after 6.00 pm. COUNCIL MEETING 7 AUGUST 2017 Table of Contents Item Page Number Number 1. MEMBERSHIP .............................................................................................................. 1 2. APOLOGIES ................................................................................................................. 1 3. DISCLOSURES OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST ......................................................... 1 4. CONFIRMATION OF THE MINUTES OF COUNCIL MEETINGS ................................. 1 5. QUESTION AND SUBMISSION TIME .......................................................................... 2 6. CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS ................................................................................ 3 6.1 PEDESTRIAN CROSSINGS IN DAREBIN ........................................................... 3 6.2 PRESTON BUSINESS ADVISORY COMMITTEE - MEMBERSHIP AND AMENDED TERMS OF REFERENCE ................................................................. 9 6.3 PROPOSED SUBDIVISION AND SALE OF COUNCIL LAND AND DISCONTINUANCE AND SALE OF RIGHT OF WAY (ROAD) ADJOINING 148 WESTGARTH STREET, NORTHCOTE ...................................................... 13 6.4 EDWARDES LAKE BOATHOUSE ..................................................................... 18 6.5 WELCOMING CITIES ....................................................................................... -

Submission to the Standing Committee on Communications, Information Technology and the Arts

Submission 113 Submission to the Standing Committee on Communications, Information Technology and the Arts House of Representatives Parliament House Canberra ACT, 2600 AUSTRALIA From 3KND/ South East Indigenous Media Association Introduction 3knd is Melbourne’s Indigenous radio station. We are operated by the South East Indigenous Media Association (SEIMA) which was granted a community broadcasting licence in December 2001 by the Australian Broadcasting Authority. 3knd has been broadcasting since June 2003. 3knd is made up of Indigenous broadcasters addressing the needs and preferences of the local community. The aim of 3knd is to provide inspirational services and opportunities to local Indigenous groups and individuals…and to reach a national Indigenous audience. These services and opportunities include: Up to date information on news, sport, weather and current affairs Entertainment in the form of Indigenous music and chat, interactive talk shows, live performances and interviews Education and cultural awareness in the form of oral histories, interviews and documentaries on Indigenous life and history Training for all broadcasters, including theoretical and practical hands on training in the studio for all ages and levels of skill Opportunities for experience and employment Provide open and affordable membership and training SEIMA is deeply committed to open membership and actively encourages listeners to become directly involved by offering free training, opportunities to gain experience and affordable membership dues. Actively encourage participation of Indigenous women A further goal of SEIMA is to actively encourage participation of Indigenous women as broadcasters, writers, researchers, trainers and managers at 3knd. Teach and learn from the wider non Indigenous community SEIMA also aims to provide a broadcasting service of deep and abiding interest to the wider non Indigenous community, with the goal of increasing mutual respect, learning and reconciliation between all Australians. -

Read Mo Re in Our Latest Annual Report

Community Broadcasting Foundation Annual Report 2020 Our Vision 3 Contents Our Organisation 4 Community Broadcasting Snapshot 5 President and CEO Report 6 Our Board 7 Our People 8 Year at a Glance 9 Achieving our Strategic Priorities 10 Strengthening and Extending Community Media 12 Partnering to Provide Vital Support to Broadcasters 13 Supporting Stations through the Pandemic 14 Content Grants 15 Development & Operations Grants 19 Sector Investment 23 Grants Allocated 26 Financial Highlights 39 Cover: Gerry ‘G-man’ Lyons is the Station Manager at 3KND in Melbourne, and is also a member of our Content Grants Advisory Committee. In 2019 he was awarded the CBAA’s Station Leadership Award. The CBF acknowledges First Nations’ sovereignty and recognises the continuing connection to lands, waters and communities by Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia. We pay our respects to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, and to Elders both past and present. We support and contribute to the process of reconciliation. 2 Annual Report 2020 Our OrganisationVision A voice for every community – sharing our stories. 3 Anna and Kyra in the PAW media studios. Annual Report 2020 Our organisation is a proud This year, we have granted $19.9 million to help 232 Our Values Our champion of community organisations communicate, connect and share knowledge through radio, television and digital media. Values are the cornerstone of our community-based Organisation media – Australia’s largest Our grants support media – developed for and by the organisation, informing our decision-making. independent media sector. community – that celebrates creativity, diversity, and Community-minded multiculturalism. Community media provides access to those We care. -

Global Media

Global Media Distribution to key consumer and general media, with coverage of newspapers, television, radio, news agencies, and general/consumer publications/editors in the Americas, including the US (National Circuit), Canada and Latin America, Asia-Pacific, Europe, Middle East and Africa. Distribution to a global mobile audience via a variety of platforms and aggregators including AFP Mobile, AP Mobile and Yahoo! Finance. Full text Arabic, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish, simplified-PRC Chinese, traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean translations as well as Italian and Dutch summary translations are included based on your English-language news release. Additional translation services are available. Global Media Australian Macedonian Weekly Buderim Chronicle Central Queensland News Asia-Pacific Media Australian National Review Bunbury Herald Central Sydney Afghanistan Avon Valley Gazette Bunbury Mail Central Western Daily News Services Bairnsdale Advertiser Bundaberg Guardian Chelsea Mordialloc Mentone Associated Press/Kabul Ballina Shire Advocate Bundaberg News-Mail News American Samoa Balonne Beacon Burwood Scene China Financial Review Newspapers Barossa & Light Herald Busselton-Dunsborough Mail Chinchilla News & Murilla Samoa News Barraba Gazette Busselton-Dunsborough Times Advertiser Armenia Barrier Daily Truth Byron Shire Echo Circular Head Chronicle Television Baw Baw Shire & West Byron Shire News City Circular Shant TV Gippsland Trader Caboolture Herald City North News Australia Bay News of the Area Caboolture News City -

Community Radio Digital Launch

Lauren Zoric | Dog Day Oz PR T: 0405 793 722 E: [email protected] W: dogdayoz.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: MONDAY MARCH 21, 2011 Melbourne Community Radio Digital Launch Thursday April 14, 2011 MC: Brian ‘Rockwiz’ Nankervis Welcome to Country: Aunty Joy Guest speech: Lord Mayor, Robert Doyle Live from The Atrium, Federation Square, Melbourne 3000 11.00am sharp Nine Melbourne community radio stations will make their digital radio network debut on Thursday April 14 when for the first time all nine stations will simultaneously broadcast side-by- side live from Federation Square to commemorate this historic occasion. The nine Melbourne community stations are: 3CR PBS 89.9 LightFm 3KND 3RRR SYN 3MBS 3ZZZ Vision Australia Radio This is the first time that so many community stations have ever broadcast together anywhere in Australia – no mean feat in a broadcast sector offering so much diversity, with programming including specialist music, current affairs, youth, ethnic and services for listeners with print disabilities. Community broadcasters in other mainland capital cities are also set to launch their digital radio services over the next few weeks. Community Broadcasting Association of Australia General Manager, Kath Letch, welcomed the move to digital. “The CBAA is delighted to see community digital radio launched in Melbourne with a combined live broadcast of all nine metropolitan-wide stations. Community broadcasters will make a strong addition to the diversity and local content of digital radio services available to the Melbourne community.” Australia is one of the first countries to implement the new DAB+ format (Digital Audio Broadcasting using enhanced audio coding), which can offer text and pictures, as well as audio.