Folding a World Into Itself

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ashoke Kumar

Ashoke Kumar The boss's wife and leading actress of a leading Film Company runs off with her lead man. She is caught and taken back but not the lead man who is unceremoniously dismissed. So now the company needs a new hero. The boss decides his laboratory assistant would be the Film Company's next leading man. A bizzare film plot??? Hardly. This real life story starred the Bombay Talkies Film Company, it's boss Himansu Rai , lead actress Devika Rani and lead man Najam-ul-Hussain and last but not least its laboratory assistant Ashok Kumar. And thus began an extremely successful acting career that lasted six decades! Ashok Kumar aka Dadamoni was born Kumudlal Kunjilal Ganguly in Bhagalpur and grew up in Khandwa. He briefly studied law in Calcutta, then joined his future brother-in-law Shashadhar Mukherjee at Bombay Talkies as laboratory assistant before being made its leading man. Ashok Kumar made his debut opposite Devika Rani in Jeevan Naiya (1936) but became a well known face with Achut Kanya (1936) . Devika Rani and he did a string of films together - Izzat (1937) , Savitri (1937) , Nirmala (1938) among others but she was the bigger star and chief attraction in all those films. It was with his trio of hits opposite Leela Chitnis - Kangan (1939) , Bandhan (1940) and Jhoola (1941) that Ashok Kumar really came into his own. Going with the trend he sang his own songs and some of them like Main Ban ki Chidiya , Chal Chal re Naujawaan and Na Jaane Kidhar Aaj Meri Nao Chali Re were extremely popular! Ashok Kumar initiated a more natural style of acting compared to the prevaling style that followed theatrical trends. -

Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There Were Few Women Painters in Colonial India

I. (A) Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar Paper Coordinator Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Author Dr. Archana Verma Independent Scholar Content Reviewer (CR) Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Language Editor (LE) Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar (B) Description of Module Items Description of Module Subject Name Women’s Studies Paper Name Women and History Module Name/ Title, Women performers in colonial India description Module ID Paper- 3, Module-30 Pre-requisites None Objectives To explore the achievements of women performers in colonial period Keywords Indian art, women in performance, cinema and women, India cinema, Hindi cinema Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There were few women painters in Colonial India. But in the performing arts, especially acting, women artists were found in large numbers in this period. At first they acted on the stage in theatre groups. Later, with the coming of cinema, they began to act for the screen. Cinema gave them a channel for expressing their acting talent as no other medium had before. Apart from acting, some of them even began to direct films at this early stage in the history of Indian cinema. Thus, acting and film direction was not an exclusive arena of men where women were mostly subjects. It was an arena where women became the creators of this art form and they commanded a lot of fame, glory and money in this field. In this module, we will study about some of these women. Nati Binodini (1862-1941) Fig. 1 – Nati Binodini (get copyright for use – (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Binodini_dasi.jpg) Nati Binodini was a Calcutta based renowned actress, who began to act at the age of 12. -

R[`C Cv[ZX >`UZ¶D W`Tfd ` H`^V

( E8 F F F ,./0,1 234 #)#)* .#,/0 +#,- < 8425?O#$192##618 46$8$+2#$218?7.2123*7$#2 6+@218$16+2694 234$3)9(17 5476354)5612# 6+ +6194$+6$)+ 9461$@6+4 72#$1#7)84$1$6 6##6##$16826847*2 9766*2+$96<$163 24+6)1 4>2+656.$?6> 66 39 )+* " ,,- & G6 # 2 6 ! %% 2# # 5 46 R! #$ O P R 12 234$ ment issue during the Covid 12 234$ sacrifice anyone to meet his Pradesh gets seven Ministers, era and gave enough fodder to 12 234$ the pandemic. Apart from political and governance objec- including Annupriya Patel of n dropping four top level the foreign media to inflict health, Dr Vardhan also held n a major Cabinet overhaul, tives. Aapna Dal (S), an NDA ally IUnion Ministers — Ravi heavy damage on the Modi e was always at the front- two Ministries — science and Iseen as a mid-term appraisal Despite the slogans of and Gujarat has five represen- Shankar Prasad, Prakash Government . Hline shielding the Modi led technology and earth sciences. of his Ministers and resetting “sabka sath sabka vikash,” the tations in the council of Javadekar, Harsh Vardhan, " The others axed a couple of Government’s Covid-19 man- The resignation is seen by Government’s profile post- Cabinet reshuffle has been Ministers. Karnataka is up by Ramesh Pokhriyal “Nishank” ! # hours before the oath-taking agement and Covid-19 vacci- the Government’s critics as an Covid-19 for the next three- based on caste consideration at four Ministers which includes and eight other Ministers — ceremony of new inductions, nation policy, but it did not admission that the pandemic year term, the Prime Minister every level. -

Unit Indian Cinema

Popular Culture .UNIT INDIAN CINEMA Structure Objectives Introduction Introducing Indian Cinema 13.2.1 Era of Silent Films 13.2.2 Pre-Independence Talkies 13.2.3 Post Independence Cinema Indian Cinema as an Industry Indian Cinema : Fantasy or Reality Indian Cinema in Political Perspective Image of Hero Image of Woman Music And Dance in Indian Cinema Achievements of Indian Cinema Let Us Sum Up Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises A 13.0 OBJECTIVES This Unit discusses about Indian cinema. Indian cinema has been a very powerful medium for the popular expression of India's cultural identity. After reading this Unit you will be able to: familiarize yourself with the achievements of about a hundred years of Indian cinema, trace the development of Indian cinema as an industry, spell out the various ways in which social reality has been portrayed in Indian cinema, place Indian cinema in a political perspective, define the specificities of the images of men and women in Indian cinema, . outline the importance of music in cinema, and get an idea of the main achievements of Indian cinema. 13.1 INTRODUCTION .p It is not possible to fully comprehend the various facets of modern Indan culture without understanding Indian cinema. Although primarily a source of entertainment, Indian cinema has nonetheless played an important role in carving out areas of unity between various groups and communities based on caste, religion and language. Indian cinema is almost as old as world cinema. On the one hand it has gdted to the world great film makers like Satyajit Ray, , it has also, on the other hand, evolved melodramatic forms of popular films which have gone beyond the Indian frontiers to create an impact in regions of South west Asia. -

Bollywood Bourgeois Author(S): Rachel Dwyer Source: India International Centre Quarterly, Vol

Bollywood Bourgeois Author(s): Rachel Dwyer Source: India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 3/4, India 60 (WINTER 2006-SPRING 2007), pp. 222-231 Published by: India International Centre Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23006084 . Accessed: 07/11/2013 09:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. India International Centre is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to India International Centre Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 146.96.128.36 on Thu, 7 Nov 2013 09:20:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions INDIA 60 Bollywood Bourgeois cliche of Indian cinema being the domain of the escapist fantasies of the Indian masses can now be safely put to rest. While this may have been true for The the 1980s, when the study of Indian cinema began to grow, the present cinema audiences, who are willing to pay Rs. 200 and upwards for a cinema ticket, are from various sections of the Indian middle classes and elites. These classes now dominate the public sphere in India and film is one of the major media which they are producing and consuming. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

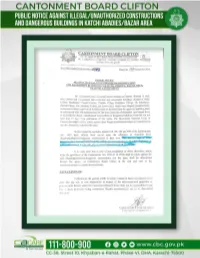

Public Notice Against Illegal / Unauthorized Constructions

CANTONMENT BOARD CLIFTON CC-38, Street 10, Kh-e-Rahat, Phase-VI, DHA, Karachi-75500 Ph. # 35847831-2, 35348774-5, 35850403, 35348784, Fax 5847835 Website: www.cbc.gov.pk _____________________________________ No. CBC/Lands/Publication/012/ Dated the 16 December 2020. PUBLIC NOTICE AGAINST ILLEGAL/UNAUTHORIZED CONSTRUCTION AND DANGEROUS BUILDINGS IN KATCHI ABADIES/BAZAR AREA CLIFTON CANTONMENT All concerned/owners/occupants/lessees/tenants are hereby directed in their own interest and convenience that residential and commercial buildings situated at Delhi Colony, Madniabad, Punjab Colony, Chandio Village, Bukhshan Village, Ch. Khaliq-uz-Zaman Colony, Pak Jamhoria Colony and Lower Gizri, which were illegally/unauthorizedly constructed without approval of building plans or deviated from the approved building plans or constructed with sub- standard material and may cause loss of properties and human lives, to demolish the illegal, unauthorized constructions or dangerous buildings forthwith but not later than 15 days from publication of this notice. The Honourable Supreme Court of Pakistan has taken serious notice against these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions and also directed to demolish the same. In this regard the requisites notices U/S 126, 185 and 256 of the Cantonments Act, 1924 have already been served upon the offenders to demolish these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions at their own. The details of such properties are as under:- DEHLI COLONY NO.01 S. Property Name of present owner Violation/ status of Name of original Lessee No. No. as per record of CBC illegal construction 1 A-01/01 Mr. Noor Bat Khan Mrs. Abida Noor Ground + 7th Floor 2 A-01/02 Mr. -

Unit-2 Silent Era to Talkies, Cinema in Later Decades

Bachelor of Arts (Honors) in Journalism& Mass Communication (BJMC) BJMC-6 HISTORY OF THE MEDIA Block - 4 VISUAL MEDIA UNIT-1 EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY, LITHOGRAPHY AND CINEMA UNIT-2 SILENT ERA TO TALKIES, CINEMA IN LATER DECADES UNIT-3 COMING OF TELEVISION AND STATE’S DEVELOPMENT AGENDA UNIT-4 ARRIVAL OF TRANSNATIONAL TELEVISION; FORMATION OF PRASAR BHARATI The Course follows the UGC prescribed syllabus for BA(Honors) Journalism under Choice Based Credit System (CBCS). Course Writer Course Editor Dr. Narsingh Majhi Dr. Sudarshan Yadav Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Journalism and Mass Communication Dept. of Mass Communication, Sri Sri University, Cuttack Central University of Jharkhand Material Production Dr. Manas Ranjan Pujari Registrar Odisha State Open University, Sambalpur (CC) OSOU, JUNE 2020. VISUAL MEDIA is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licences/by-sa/4.0 Printedby: UNIT-1EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY, LITHOGRAPHY AND CINEMA Unit Structure 1.1. Learning Objective 1.2. Introduction 1.3. Evolution of Photography 1.4. History of Lithography 1.5. Evolution of Cinema 1.6. Check Your Progress 1.1.LEARNING OBJECTIVE After completing this unit, learners should be able to understand: the technological development of photography; the history and development of printing; and the development of the motion picture industry and technology. 1.2.INTRODUCTION Learners as you are aware that we are going to discuss the technological development of photography, lithography and motion picture. In the present times, the human society is very hard to think if the invention of photography hasn‘t been materialized. It is hard to imagine the world without photography. -

Sample Pages

Between the Studio and the World Built Sets and Outdoor Locations in the Films of Bombay Talkies ¢ Debashree Mukherjee ¢ Cinema is a form that forces us to question distinctions between the natural world and a world made by humans. Film studios manufacture natural environments with as much finesse as they fabricate built environments. Even when shooting outdoors, film crews alter and choreograph their surroundings in order to produce artful visions of nature. This historical proclivity has led theorists such as Jennifer Fay to name cinema as the “aesthetic practice of the Anthropocene,” that is, an art form that intervenes in and interferes with the natural world, mirroring humankind’s calamitous impact on the planet since the Industrial Revolution (2018, 4). In what follows, my concern is with thinking about how the indoor and the outdoor, Publishingthe world of the studio and the many worlds outside, are co-constituted through the act of filming. I am interested in how we can think of a mutual exertion of spatial influence and the co-production of space by multiple actors. Once framed by the camera, nature becomes a set of values (purity, regeneration, unpredictability), as does the city (freedom, anonymity, danger). The Wirsching collection allows us to examine these values and their construction by keeping in view both the filmed narrative as well as parafilmic images of production. By examining the physical and imaginative worlds that were manufactured in the early films of Bombay Talkies—built sets, Mapin painted backdrops, carefully calibrated outdoor locations—I pursue some meanings of “place” that unfold outwards from the film frame, and how an idea of place is critical to establishing the identity of characters. -

S. No. Name of the Project Anganwadi Centre No. Name of The

ICDS Projects S. No. Name of the Anganwadi Name of the Name of the Address of the Anganwadi Project Centre No. Anganwadi Anganwadi Centre Worker Helper Babarpur 1 Neetu Lalita Gali Number - 49, D Block, Janta Mazdoor Colony 2 Pavitra Chetna D - 362, Janta Mazdoor Colony 3 Virendri Vimlesh D - 282, Janta Mazdoor Colony 4 Chandresh Pal Geeta Sharma L - 392, Janta Mazdoor Colony 5 Archana Raj Kumari A - 49, B - 383, Janta Mazdoor Colony 6 Bharti Pandey Meena B - 334, Janta Mazdoor Colony 7 Vijay Laxmi Deepali Jamshed Anwar - 49 / L - Jaidev 350, Janta Mazdoor Colony 8 Vijay Laxmi Devki Aklota L - 132, Gali Number - 27, Janta Mazdoor Colony 9 Rajni Anju Sharma K - 97, Janta Mazdoor Colony, Gali Number - 5 10 Manju Sharma Vimlesh Deva K - 336, Chaman Panwali, Sushil Gali Number - 4 11 Babita Sonia F - 555, Nazta, Mazdoor Colony 12 Manju Sharma Geeta Vikas F - 179, Janta Mazdoor Devender Colony 1 13 Bharti Vandarna I - 30, Janta Mazdoor Maheswari Colony 14 Akshma Sharma Sunita Om I - 58, Block Khazoor Wali Gali, Janta Mazdoor Colony 15 Sangeeta Poonam Goyal A - 338, Idgah Road, Janta Mazdoor Colony 16 Jayshree Poonam Pawan J - 160, Janta Mazdoor Colony 17 Anjana Kaushik Shradha E - 49, B - 60, Janta Mazdoor Colony 18 Pooja Kaushik Sarvesh E - 49, D - 265, Janta Mazdoor Colony 19 Neetu Singh Rita Sharma E - 49, E - 11, Janta Mazdoor Colony 20 Konika Sharma Sunita Anil E - 49 / 128, Janta Mazdoor Colony 21 Monika Sharma Prem Lata D - 96, Gali Number - 3, Janta Mazdoor Colony 22 Rajeshwari Poonam Manoj W - 586, Gali Number - 3 / 8, Sudama Puri -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

Download Download

Kervan – International Journal of Afro-Asiatic Studies n. 21 (2017) Item Girls and Objects of Dreams: Why Indian Censors Agree to Bold Scenes in Bollywood Films Tatiana Szurlej The article presents the social background, which helped Bollywood film industry to develop the so-called “item numbers”, replace them by “dream sequences”, and come back to the “item number” formula again. The songs performed by the film vamp or the character, who takes no part in the story, the musical interludes, which replaced the first way to show on the screen all elements which are theoretically banned, and the guest appearances of film stars on the screen are a very clever ways to fight all the prohibitions imposed by Indian censors. Censors found that film censorship was necessary, because the film as a medium is much more popular than literature or theater, and therefore has an impact on all people. Indeed, the viewers perceive the screen story as the world around them, so it becomes easy for them to accept the screen reality and move it to everyday life. That’s why the movie, despite the fact that even the very process of its creation is much more conventional than, for example, the theater performance, seems to be much more “real” to the audience than any story shown on the stage. Therefore, despite the fact that one of the most dangerous elements on which Indian censorship seems to be extremely sensitive is eroticism, this is also the most desired part of cinema. Moreover, filmmakers, who are tightly constrained, need at the same time to provide pleasure to the audience to get the invested money back, so they invented various tricks by which they manage to bypass censorship.