Communication 140 Introduction to Film Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Me and Orson Welles Press Kit Draft

presents ME AND ORSON WELLES Directed by Richard Linklater Based on the novel by Robert Kaplow Starring: Claire Danes, Zac Efron and Christian McKay www.meandorsonwelles.com.au National release date: July 29, 2010 Running time: 114 minutes Rating: PG PUBLICITY: Philippa Harris NIX Co t: 02 9211 6650 m: 0409 901 809 e: [email protected] (See last page for state publicity and materials contacts) Synopsis Based in real theatrical history, ME AND ORSON WELLES is a romantic coming‐of‐age story about teenage student Richard Samuels (ZAC EFRON) who lucks into a role in “Julius Caesar” as it’s being re‐imagined by a brilliant, impetuous young director named Orson Welles (impressive newcomer CHRISTIAN MCKAY) at his newly founded Mercury Theatre in New York City, 1937. The rollercoaster week leading up to opening night has Richard make his Broadway debut, find romance with an ambitious older woman (CLAIRE DANES) and eXperience the dark side of genius after daring to cross the brilliant and charismatic‐but‐ sometimes‐cruel Welles, all‐the‐while miXing with everyone from starlets to stagehands in behind‐the‐scenes adventures bound to change his life. All’s fair in love and theatre. Directed by Richard Linklater, the Oscar Nominated director of BEFORE SUNRISE and THE SCHOOL OF ROCK. PRODUCTION I NFORMATION Zac Efron, Ben Chaplin, Claire Danes, Zoe Kazan, Eddie Marsan, Christian McKay, Kelly Reilly and James Tupper lead a talented ensemble cast of stage and screen actors in the coming‐of‐age romantic drama ME AND ORSON WELLES. Oscar®‐nominated director Richard Linklater (“School of Rock”, “Before Sunset”) is at the helm of the CinemaNX and Detour Filmproduction, filmed in the Isle of Man, at Pinewood Studios, on various London locations and in New York City. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Montana Kaimin, October 20, 1961 Associated Students of Montana State University

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 10-20-1961 Montana Kaimin, October 20, 1961 Associated Students of Montana State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of Montana State University, "Montana Kaimin, October 20, 1961" (1961). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 3744. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/3744 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Montana Kainun Friday, October 20, 1961 Montana State University “Expressing 64 Years of Editorial Freedom” 64th Year of Publication, No. 15 Missoula, Montana MLEA Brings Big Band Man 327 Students Ralph Marterie T o MSU Today Plays Tonight Ralph Marterie, “Big Band Man” The 12th annual Montana Inter will be playing for an ASMSU scholastic Editorial Association dance tonight from 8:30 to 12:30 in meeting began this morning with the Cascade Room of the Lodge. the arrival and registration of 327 The dance is semiformal and high school journalists from 41 tickets are being sold at $3 per schools. couple in the Lodge or may be pur Miss Peggy Jones of Laurel will chased at the door. preside over the Friday and Sat Marterie specializes in instru urday general sessions. -

THE MAGAZINE of MISSOURI WESTERN STATE UNIVERSITY Fall 2016 3 20 Campus News Campus News

The magazineMissouri of Missouri Western State University Western Fall 2016 President’s Perspective Student service abounds! Dear Friends, We were honored and grateful that Top left, nursing students recently raised As I write this letter, one word comes the King family gave Missouri Western funds for St. Joseph’s Social Welfare Board; to mind: BIG. And I think of BIG for permission to create the show. top right, the Organization of Student Social Workers annually hosts A Walk for the two reasons. And there was more BIG news. By Homeless, an informational event for the First, by the time you receive this the end of September 2016, the live, community; middle and lower left, students in magazine, Missouri Western will be home multimedia shows will have been shown the Department of Health, Physical Education to one of the largest video scoreboards in at the Truman Presidential Library in and Recreation host elementary students NCAA Division II – 2,500 square feet. Independence, Missouri; Union Station in for the annual American Heart Association’s Photos and an article about it are on p. 20, Kansas City, Missouri; in New York City fundraiser, Jump Rope for Heart, and the and more photos are on the back cover. and at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. Golden Age Games for area nursing home That is an outstanding component That’s BIG. residents; bottom right, the Department of the new Spratt Memorial Stadium If you haven’t seen all three shows, of Music students and faculty entertained that was completed this past spring. If check out the website – missouriwestern. -

A Reappraisal of Three Character Actors from Hollywood’S Golden Age

University of the Incarnate Word The Athenaeum Theses & Dissertations 12-2015 Second-Billed but not Second-Rate: A Reappraisal of Three Character Actors From Hollywood’s Golden Age Candace M. Graham University of the Incarnate Word, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://athenaeum.uiw.edu/uiw_etds Part of the Communication Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Graham, Candace M., "Second-Billed but not Second-Rate: A Reappraisal of Three Character Actors From Hollywood’s Golden Age" (2015). Theses & Dissertations. 70. https://athenaeum.uiw.edu/uiw_etds/70 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Athenaeum. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Athenaeum. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SECOND-BILLED BUT NOT SECOND-RATE: A REAPPRAISAL OF THREE CHARACTER ACTORS FROM HOLLYWOOD’S GOLDEN AGE by Candace M. Graham A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the University of the Incarnate Word in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS University of the Incarnate Word December 2015 ii Copyright 2015 by Candace M. Graham iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Dr. Hsin-I (Steve) Liu for challenging me to produce a quality thesis worthy of contribution to scholarly literature. In addition, thank you for the encouragement to enjoy writing. To Robert Darden, Baylor University communications professor, friend, and mentor whose example in humility, good spirit, and devotion to one’s passion continues to guide my pursuit as a classic film scholar. -

Tommy Dorsey 1 9

Glenn Miller Archives TOMMY DORSEY 1 9 3 7 Prepared by: DENNIS M. SPRAGG CHRONOLOGY Part 1 - Chapter 3 Updated February 10, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS January 1937 ................................................................................................................. 3 February 1937 .............................................................................................................. 22 March 1937 .................................................................................................................. 34 April 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 53 May 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 68 June 1937 ..................................................................................................................... 85 July 1937 ...................................................................................................................... 95 August 1937 ............................................................................................................... 111 September 1937 ......................................................................................................... 122 October 1937 ............................................................................................................. 138 November 1937 ......................................................................................................... -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

Eoff Runs Away with Honor the Death Penalty Affects Society

I Entertainment 1 Features 1 Sports Chestnut Station hosts 5% B Dieting has been around forever Burgess Lands I See page 11 I See page 13 I See page 14 THE CHANTICLEER Jacksonville State University Vol. 32No. 31 Jacksonvrlle. Alabama May 23, 1985 Wrong or right The death penalty affects society By VICKY WALLACE Does a fist degree murderer deserve the death penalty? Can the death penalty serve as a deterrent? Who usually gets the death penalty? Is capital punishment wrong or right? These and other questions are being studied in Dr. Robert Bohm's Capital Punishment class this minimester. So far, Dr. Bohm's class has been studying historical aspects of the death penalty and Supreme Court cases dealing with the death penalty. Later on in their studies, the class will be talking about issues of deterrence. "We'll look at the question of whether or not the death penalty prevents other people from committing violent crimes by looking at evidence. Then we'll look at how the death penalty is actually administered in the United States,Dr. Bohm said.When a person is sentenced to death, thelperson may be either electrocuted, killed by a f-g squad, forced to inhale cyanide gas, hanged,,or given a lethalinjection,but it is up to each state which method is used. One might assume that the newest method, lethal in- jection, would be the most 'humane' or least painful, but according to Dr. Bohm, problems arise if any of the methods of capital punishment are not administered properly. "Lethal injection involves a combination of an ultra-short working barbituate, which is a central nervous system photo by Jerry Harris depressant,and a paralytic agent. -

The Media Assemblage: the Twentieth-Century Novel in Dialogue with Film, Television, and New Media

THE MEDIA ASSEMBLAGE: THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY NOVEL IN DIALOGUE WITH FILM, TELEVISION, AND NEW MEDIA BY PAUL STEWART HACKMAN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Robert Markley Associate Professor Jim Hansen Associate Professor Ramona Curry ABSTRACT At several moments during the twentieth-century, novelists have been made acutely aware of the novel as a medium due to declarations of the death of the novel. Novelists, at these moments, have found it necessary to define what differentiates the novel from other media and what makes the novel a viable form of art and communication in the age of images. At the same time, writers have expanded the novel form by borrowing conventions from these newer media. I describe this process of differentiation and interaction between the novel and other media as a “media assemblage” and argue that our understanding of the development of the novel in the twentieth century is incomplete if we isolate literature from the other media forms that compete with and influence it. The concept of an assemblage describes a historical situation in which two or more autonomous fields interact and influence one another. On the one hand, an assemblage is composed of physical objects such as TV sets, film cameras, personal computers, and publishing companies, while, on the other hand, it contains enunciations about those objects such as claims about the artistic merit of television, beliefs about the typical audience of a Hollywood blockbuster, or academic discussions about canonicity. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Citizen Kane Ebook, Epub

CITIZEN KANE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harlan Lebo | 368 pages | 01 May 2016 | Thomas Dunne Books | 9781250077530 | English | United States Citizen Kane () - IMDb Mankiewicz , who had been writing Mercury radio scripts. One of the long-standing controversies about Citizen Kane has been the authorship of the screenplay. In February Welles supplied Mankiewicz with pages of notes and put him under contract to write the first draft screenplay under the supervision of John Houseman , Welles's former partner in the Mercury Theatre. Welles later explained, "I left him on his own finally, because we'd started to waste too much time haggling. So, after mutual agreements on storyline and character, Mank went off with Houseman and did his version, while I stayed in Hollywood and wrote mine. The industry accused Welles of underplaying Mankiewicz's contribution to the script, but Welles countered the attacks by saying, "At the end, naturally, I was the one making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank's and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own. The terms of the contract stated that Mankiewicz was to receive no credit for his work, as he was hired as a script doctor. Mankiewicz also threatened to go to the Screen Writers Guild and claim full credit for writing the entire script by himself. After lodging a protest with the Screen Writers Guild, Mankiewicz withdrew it, then vacillated. The guild credit form listed Welles first, Mankiewicz second. Welles's assistant Richard Wilson said that the person who circled Mankiewicz's name in pencil, then drew an arrow that put it in first place, was Welles. -

John Cassavetes, Director De Cinc Capítols

bobila.blogspot.com el fanzine del “Club de Lectura de Novel·la Negra” de la Biblioteca la Bòbila # 119 Biblioteca la bòbila. L’hospitalet / esplugues L'H Confidencial 1 Johnny Staccato és un pianista de jazz frustrat criat a Little Italy, bressol de la màfia italoamericana de Nova York. Es guanya la vida exercint de detectiu privat, però no té oficina. Rep els seus clients al Waldo’s, un club de jazz del Greenwich Village, habitual centre de reunió de la Beat Generation i de la bohemia novaiorquesa de finals dels cinquanta i començaments dels seixanta. Sèrie realitzada el 1959-60, Johnny Staccato està protagonitzada pel llegendari John Cassavetes, director de cinc capítols. Combina la bona música, violencia i intrigues policíaques en un còctel únic, tractat sense embuts temàtiques tant agosarades (per John Cassavetes a l’època) com el sexe, la religió, les drogues, el tràfic d’infants o l’anticomunisme. La sèrie va plegar després de 27 capítols, John Cassavetes nace el 9 de diciembre de 1929 en Nueva York, en una alguns judicats “massa controvertits” per la productora. familia de origen griego. A principio de los años cincuenta ingresa en la Ara, per primera vegada a Espanya es pot veure la única Academy of Dramatic Arts en Nueva York, fuertemente influida por el temporada completa d’aquesta sèrie d’alta qualitat técnica, estilo del Actor's Studio. En marzo de 1954 se casa con una joven artística i narrativa, amb actors de la talla de John Cassavetes, actriz, Gena Rowlands, que le acompañará toda su vida. Tras Elisha Cook Jr., Cloris Leachman, Gena Rowlands, Elizabeth numerosos pequeños papeles en telefilmes y películas de segunda fila Montgomery, Michael Landon i Dean Stockwell, i dirigida per rueda en 1956 sus dos primeras películas como protagonista, Crime in respectats directors com John Cassavetes, Boris Sagal, John the Streets, de Don Siegel y Edge of the City, de Martin Ritt. -

The Booklet That Accompanied the Exhibition, With

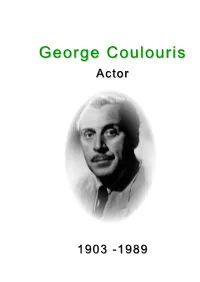

GGeeoorrggee CCoouulloouurriiss AAccttoorr 11990033 --11998899 George Coulouris - Biographical Notes 1903 1st October: born in Ordsall, son of Nicholas & Abigail Coulouris c1908 – c1910: attended a local private Dame School c1910 – 1916: attended Pendleton Grammar School on High Street c1916 – c1918: living at 137 New Park Road and father had a restaurant in Salisbury Buildings, 199 Trafford Road 1916 – 1921: attended Manchester Grammar School c1919 – c1923: father gave up the restaurant Portrait of George aged four to become a merchant with offices in Salisbury Buildings. George worked here for a while before going to drama school. During this same period the family had moved to Oakhurst, Church Road, Urmston c1923 – c1925: attended London’s Central School of Speech and Drama 1926 May: first professional stage appearance, in the Rusholme (Manchester) Repertory Theatre’s production of Outward Bound 1926 October: London debut in Henry V at the Old Vic 1929 9th Dec: Broadway debut in The Novice and the Duke 1933: First Hollywood film Christopher Bean 1937: played Mark Antony in Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre production of Julius Caesar 1941: appeared in the film Citizen Kane 1950 Jan: returned to England to play Tartuffe at the Bristol Old Vic and the Lyric Hammersmith 1951: first British film Appointment With Venus 1974: played Dr Constantine to Albert Finney’s Poirot in Murder On The Orient Express. Also played Dr Roth, alongside Robert Powell, in Mahler 1989 25th April: died in Hampstead John Koulouris William Redfern m: c1861 Louisa Bailey b: 1832 Prestbury b: 1842 Macclesfield Knutsford Nicholas m: 10 Aug 1902 Abigail Redfern Mary Ann John b: c1873 Stretford b: 1864 b: c1866 b: c1861 Greece Sutton-in-Macclesfield Macclesfield Macclesfield d: 1935 d: 1926 Urmston George Alexander m: 10 May 1930 Louise Franklin (1) b: Oct 1903 New York Salford d: April 1989 d: 1976 m: 1977 Elizabeth Donaldson (2) George Franklin Mary Louise b: 1937 b: 1939 Where George Coulouris was born Above: Trafford Road with Hulton Street going off to the right.