The Next Point Annual 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

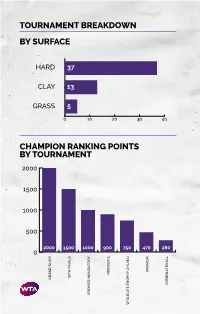

Tournament Breakdown by Surface Champion Ranking Points By

TOURNAMENT BREAKDOWN BY SURFACE HAR 37 CLAY 13 GRASS 5 0 10 20 30 40 CHAMPION RANKING POINTS BY TOURNAMENT 2000 1500 1000 500 2000 1500 1000 900 750 470 280 0 PREMIER PREMIER TA FINALS TA GRAN SLAM INTERNATIONAL PREMIER MANATORY TA ELITE TROPHY HUHAI TROPHY ELITE TA 55 WTA TOURNAMENTS BY REGION BY COUNTRY 8 CHINA 2 SPAIN 1 MOROCCO UNITED STATES 2 SWITZERLAND 7 OF AMERICA 1 NETHERLANDS 3 AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRIA 1 NEW ZEALAND 3 GREAT BRITAIN 1 COLOMBIA 1 QATAR 3 RUSSIA 1 CZECH REPUBLIC 1 ROMANIA 2 CANADA 1 FRANCE 1 THAILAND 2 GERMANY 1 HONG KONG 1 TURKEY UNITED ARAB 2 ITALY 1 HUNGARY 1 EMIRATES 2 JAPAN 1 SOUTH KOREA 1 UZBEKISTAN 2 MEXICO 1 LUXEMBOURG TOURNAMENTS TOURNAMENTS International Tennis Federation As the world governing body of tennis, the Davis Cup by BNP Paribas and women’s Fed Cup by International Tennis Federation (ITF) is responsible for BNP Paribas are the largest annual international team every level of the sport including the regulation of competitions in sport and most prized in the ITF’s rules and the future development of the game. Based event portfolio. Both have a rich history and have in London, the ITF currently has 210 member nations consistently attracted the best players from each and six regional associations, which administer the passing generation. Further information is available at game in their respective areas, in close consultation www.daviscup.com and www.fedcup.com. with the ITF. The Olympic and Paralympic Tennis Events are also an The ITF is committed to promoting tennis around the important part of the ITF’s responsibilities, with the world and encouraging as many people as possible to 2020 events being held in Tokyo. -

Mississippi State Men's Tennis History

MISSISSIPPI STATE MEN’S TENNIS HISTORY 1965: Southeastern Conference Champions 1967: Southeastern Conference Champions 1992: Southeastern Conference Regular Season Champions 1992: Southeastern Conference Indoors "Mythical" Team Champions 1992: Blue-Gray National Collegiate Classic Champions 1993: Southeastern Conference Regular Season Champions 1993: Southeastern Conference Champions 1996: Southeastern Conference Tournament Champions 2011: Southeastern Conference Western Division Champions 2012: Blue-Gray National Collegiate Classic Champions 2012: Southeastern Conference Western Division Champions S 2018: Southeastern Conference Tournament Champions 2019: Southeastern Conference Tournament Champions HIP S 1993 SEC CHAMPIONS FRONT ROW (L-R): MANAGER DREW ANTHONY, JOHN HALL, REMI BARBARIN, STEPHANE PLOT, SYLVAIN GUICHARD, MANAGER SHANNON JENKINS, ASSISTANT COACH DWAYNE CLEGG. BACK ROW (L-R): JEREMY ALLEY, MARC SIMS, DANIEL COURCOL, LAURENT ORSINI, PION LAURENT MIQUELARD, CHASE HENSON, PER NILSSON, KRISTIAN BROEMS, UNDERGRADUATE ASSISTANT HRISTOPHE AMIENS RETT LIDEWELL EAD OACH NDY ACKSON M C D , B G , H C A J . HA C M EA 1965 SEC CHAMPIONS FRONT ROW (L-R): GRAHAM PRIMROSE, PHIL LIVINGSTON, ROBERT DEAN, ORLANDO BRACAMONTE. BACK ROW (L-R): HEAD COACH TOM SAWYER, HAGAN STATON, MACK CAMERON, TITO ECHIBURU, BOBBY BRIEN, MANAGER GEORGE BIDDLE. MSU T 2011 SEC WESTERN DIVISION CHAMPIONS FRONT ROW (L-R): HREHAN HAKEEM, ARTEM ILYUSHIN, TREY SEYMOUR, ANTONIO LASTRE, LOUIS CANT, ASSISTANT COACH MATT HILL. BACK ROW (L-R): VOLUNTEER ASSISTANT COACH CHRIS DOERR, MALTE STROPP, TANNER STUMP, MAX GREGOR, GEORGE COUPLAND, ZACH WHITE, JAMES CHAUDRY, HEAD COACH PER NILSSON. 1967 SEC CHAMPIONS FRONT ROW (L-R): JOHN EDMOND, BOBBY BRIEN, PIERRE LAMARCHE, HUGH THOMSON. BACK ROW (L-R): HEAD COACH TOM SAWYER, ROB CADWALLADER, GLEN GRISILLO, MACK CAMERON, GARY HOCKEY, TED JONES, GRADUATE ASSISTANT COACH GRAHAM PRIMROSE. -

VICTOR ESTRELLA BURGOS (Dom) DATE of BIRTH: August 2, 1980 | BORN: Santiago, Dominican Republic | RESIDENCE: Santiago, Dominican Republic

VICTOR ESTRELLA BURGOS (dOm) DATE OF BIRTH: August 2, 1980 | BORN: Santiago, Dominican Republic | RESIDENCE: Santiago, Dominican Republic Turned Pro: 2002 EmiRATES ATP RAnkinG HiSTORy (W-L) Height: 5’8” (1.73m) 2014: 78 (9-10) 2009: 263 (4-0) 2004: T1447 (3-1) Weight: 170lbs (77kg) 2013: 143 (2-1) 2008: 239 (2-2) 2003: T1047 (3-1) Career Win-Loss: 39-23 2012: 256 (6-0) 2007: 394 (3-0) 2002: T1049 (0-0) Plays: Right-handed 2011: 177 (2-1) 2006: 567 (2-2) 2001: N/R (2-0) Two-handed backhand 2010: 219 (0-3) 2005: N/R (1-2) Career Prize Money: $635,950 8 2014 HiGHLiGHTS Career Singles Titles/ Finalist: 0/0 Prize money: $346,518 Career Win-Loss vs. Top 10: 0-1 Matches won-lost: 9-10 (singles),4-5 (doubles) Challenger: 28-11 (singles), 4-7 (doubles) Highest Emirates ATP Ranking: 65 (October 6, 2014) Singles semi-finalist: Bogota Highest Emirates ATP Doubles Doubles semi-finals: Atlanta (w/Barrientos) Ranking: 145 (May 25, 2009) 2014 IN REVIEW • In 2008, qualified for 1st ATP tournament in Cincinnati (l. to • Became 1st player from Dominican Republic to finish a season Verdasco in 1R). Won 2 Futures titles in Dominican Republic in Top 100 Emirates ATP Rankings after climbing 65 places • In 2007, won 5 Futures events in U.S., Nicaragua and 3 on home during year soil in Dominican Republic • Reached maiden ATP World Tour SF in Bogota in July, defeating • In 2006, reached 3 Futures finals in 3-week stretch in the U.S., No. -

DI-P15-15-1-(P)- Tas.Qxd

Saturday 15th January, 2010 15 Australian Open men’s capsules BY DENNIS PASSA MELBOURNE, Australia (AP) - Men to watch at the Australian Open, which begins Monday (rankings in parenthe- ses): ANDY MURRAY (5) Age: 23 Country: Britain 2010 Singles Titles: 2 Career Singles Titles: 16 Major Titles: 0 Last 5 Australian Opens: ‘10-F, ‘09-4th, ‘08-1st, ‘07-4th, RAFAEL NADAL (1) ‘06-1st, ‘05-DNP. Topspin: Murray is 0-2 in Grand Slam finals - both loss- es to Roger Federer, at the 2008 U.S. Open and 2010 Australian RAFAEL NADAL (1) Open - and he’s trying to become the first British man to win Age: 24 last year’s French Open, Wimbledon a major championship since Fred Perry in 1936. The pressure Country: Spain and U.S. Open. That would take his of that task showed when he made a tearful speech after last 2010 Match Record: 71-10 Grand Slam total to 10. The Spaniard is year’s loss at Rod Laver Arena. Played with British team- 2010 Singles Titles: 7 aiming to be the first man since Rod mate Laura Robson at the Hopman Cup two weeks ago, and Career Singles Titles: 43 Laver to hold all four Grand Slam tro- the Kooyong exhibition this week to try to hone his game Major Titles: 9 - Wimbledon (‘08, phies at once, although it won’t be a ahead of Melbourne Park. ‘10), Australian Open (‘09), true Grand Slam - Laver won all four in French Open (‘05, ‘06, ‘07, ‘08, ‘10), a calendar year in 1969. Got 2011 off to U.S. -

Tournament Notes

TOURNAMENT NOTES as of April 21, 2016 BOYD TINSLEY CLAY COURT CLASSIC CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA • APRIL 24-MAY 1 USTA PRO CIRCUIT WOMEN’S TENNIS RETURNS TO CHARLOTTESVILLE FOR 15TH YEAR, CONTINUES USTA PRO CIRCUIT ROLAND GARROS WILD CARD CHALLENGE The Boyd Tinsley Clay Court Classic returns to TOURNAMENT Charlottesville for the 15th consecutive year. INFORMATION It is the only USTA Pro Circuit women’s event held in Virginia. Charlottesville also hosts a Ryan USTA/Steven Site: Boar’s Head Sports Club $50,000 USTA Pro Circuit men’s Challenger in Charlottesville, Va. early November and, for the first time, will host a $25,000 men’s event in June to kick off the Websites: www.boarsheadinn.com new USTA Pro Circuit Collegiate Series. procircuit.usta.com Qualifying Draw Begins: Sunday, April 24 Charlottesville is also one of three consecutive women’s clay-court tournaments (joining last Main Draw Begins: Tuesday, April 26 week’s $50,000 event in Dothan, Ala., and Main Draw: 32 Singles / 16 Doubles next week’s $75,000 event in Indian Harbour Beach, Fla.) that are part of the USTA Pro Surface: Clay / Outdoor Circuit Roland Garros Wild Card Challenge, Prize Money: $50,000 which will award a men’s and women’s wild card into the 2016 French Open. Along with Tournament Director: these three women’s tournaments, the men’s Top seed and 2013 Charlottesville singles champion Shelby Rogers advanced to the third Ron Manilla, (434) 960-3364 tournaments that are part of the challenge round at the 2015 US Open as a qualifier. -

Successful Execution of Growth Strategy

Perform Group plc Annual Report and Successful execution Accounts 2012 of growth strategy ABOUT US Perform is a global market leader in the commercialisation of multimedia sports content across multiple platforms. The Group licenses one of the largest portfolios of digital sports rights in the world, through contracts relating to more than 200 sports leagues, tournaments and events. The Group’s Management is focused on driving earnings growth through leveraging its content across new digital platforms, new products and across new geographies, taking advantage of favourable technology trends such as growth in digital media consumption and online video viewership. www.performgroup.co.uk OVERVIEW Financial highlights OVERVIEW OVERVIEW Revenue (£’000) Financial highlights 1 Business at a glance 4 151,607 Market overview 6 Chairman/Joint CEOs’ review 10 Year on year growth of 47% Vision and growth strategy 12 2010 67,430 Enhance digital sports rights portfolio 14 2011 103,194 Expand geographically 16 2012 151,607 Grow the audience 18 Pursue complementary strategic acquisitions 19 Launch on new digital platforms 20 Adjusted EBITDA 1 (£’000) 2013: Investment for future growth 22 BUSINESS AND FINANCIAL REVIEW REVIEW FINANCIAL AND BUSINESS 37,502 BUSINESS AND FINANCIAL REVIEW Year on year growth of 103% Content distribution 26 2010 10,345 Advertising & sponsorship (display) 28 2011 18,474 Advertising & sponsorship (video) 30 2012 37,502 Subscription 32 Technology & production 34 Financial review 36 Adjusted profit after tax 2 (£’000) 26,861 Year -

Tournament Notes

TournamenT noTes as of may 8, 2013 TAMPA USTA MEN’S PRO CIRCUIT FUTURES TAMPA, FL • MAY 10-19 USTA PRO CIRCUIT RETURNS TO TAMPA TournamenT InFormaTIon The Tampa USTA Men’s Pro Circuit Futures is being held in Tampa for the 14th consecutive Site: Harbour Island Athletic Club – Tampa, Fla. year. It also hosted nine USTA Pro Circuit events between 1980 and 1997. It is the David Kenas Website: procircuit.usta.com last of three consecutive clay-court USTA Pro Qualifying Draw Begins: Friday, May 10 Circuit Futures, all of which have been held in Florida, to synchronize the USTA Pro Circuit Main Draw Begins: Tuesday, May 14 clay-court season with the French Open. In Main Draw: 32 Singles / 16 Doubles all, there are 13 Futures scheduled to be held in Florida in 2013, all on clay. In conjunction Surface: Clay / Outdoor with USTA Player Development, the USTA Pro Prize Money: $10,000 Circuit continues to emphasize the importance of increased training for younger players on Tournament Director: clay, this year adding four additional clay-court Jose Campos, (813) 202-1950 ext. 107 tournaments to the calendar. [email protected] Tournament Press Contact: Players competing in the main draw are: Jose Campos, (813) 202-1950 ext. 107 [email protected] Chase Buchanan, the 2012 NCAA men’s doubles champion for Ohio State. On the USTA Communications Contacts: USTA Pro Circuit in 2012, Buchanan won Amanda Korba, (914) 697-2219, [email protected] two Futures singles titles and three Futures Former US Open boys’ singles finalist Chase doubles titles—all on clay. -

Tournament Notes

TournamenT noTes as of april 25, 2013 AUDI MELBOURNE PRO TENNIS CLASSIC INDIAN HARBOUR BEACH, FL • APRIL 28–MAY 5 USTA PRO CIRCUIT EVENT IN INDIAN HARBOUR BEACH CONCLUDES HAR-TRU USTA PRO CIRCUIT WILD CARD CHALLENGE The Audi Melbourne Pro Tennis Classic returns to Indian Harbour Beach, Fla., for TournamenT the eighth consecutive year. It is the fourth Hartis Tim InFormaTIon $50,000 USTA Pro Circuit clay-court event of the 2013 season and the eighth of nine consecutive clay-court events, ranging from Site: Kiwi Tennis Club – Indian Harbour Beach, Fla. $25,000 to $50,000 in prize money, to Websites: www.kiwitennisclub.com develop players on clay and prepare them for procircuit.usta.com the 2013 French Open. Facebook: Kiwi Tennis Club Indian Harbour Beach is the final of three Twitter: @KiwiTennisClub consecutive women’s clay-court tournaments (joining $50,000 events in Dothan, Ala., Wild Card Challenge Twitter: #USTAHarTruWC and Charlottesville, Va.) that are part of Qualifying Draw Begins: Sunday, April 28 the Har-Tru USTA Pro Circuit Wild Card Challenge, which will award a men’s and Main Draw Begins: Tuesday, April 30 women’s wild card into the 2013 French 2011 US Open junior champion Grace Min Main Draw: 32 Singles / 16 Doubles Open. The three women’s tournaments join captured last year’s singles title in Indian three men’s tournaments—the Sarasota Harbour Beach. Surface: Clay / Outdoors Open in Florida, held the week of April Prize Money: $50,000 15; the Savannah Challenger in Georgia, held the week of April 22; and the USTA cards into the 2013 French Open and Tournament Director: Tallahassee Tennis Challenger in Florida, US Open are exchanged. -

Match Notes Internationaux De Strasbourg - Strasbourg, France 2021-05-23 - 2021-05-29 | $ 235,238

26/05/2021 SAP Tennis Analytics 1.4.9 MATCH NOTES INTERNATIONAUX DE STRASBOURG - STRASBOURG, FRANCE 2021-05-23 - 2021-05-29 | $ 235,238 1 0 win win 1 matches played 61 Sorana Shuai Cirstea (6) Zhang 45 ROMANIA CHINA 1990-04-07 Date of Birth 1989-01-21 Targoviste, Romania Residence Tianjin, China Right-handed (two-handed backhand) Plays Right-handed (two-handed backhand) 5' 9" (1.76 m) Height 5' 10" (1.77 m) 21 Career-High Ranking 23 $6,064,123 Career Prize Money $6,952,466 $233,024 Season Prize Money $160,240 1 / 2 Singles Titles YTD / Career 0 / 2 47-48 (QF: 2009 Roland Garros) Grand Slam W-L (best) 28-34 (QF: 2019 Wimbledon; 2016 Australian Open) 1-0 / 1-1 (Second round: 2021) YTD / Career STRASBOURG W-L 1-0 / 4-4 (Quarter-Finalist: 2020) (best) 12-6 / 242-252 YTD / Career W-L 1-7 / 178-200 6-1 / 83-77 YTD / Career Clay W-L 1-5 / 31-49 2-1 / 90-75 YTD / Career 3-Set W-L 0-1 / 51-49 3-1 / 56-46 YTD / Career TB W-L 0-1 / 42-45 Champion: Istanbul YTD Best Result Second round: Strasbourg https://dev.saptennis.com/media/mediaportal/#season/2021/events/0406/matches/LS009/apps/post-match-insights/match-notes/snapshots/58b5f… 1/8 26/05/2021 SAP Tennis Analytics 1.4.9 MATCH NOTES INTERNATIONAUX DE STRASBOURG - STRASBOURG, FRANCE 2021-05-23 - 2021-05-29 | $ 235,238 Sorana Shuai Cirstea Zhang Head To Head Record YEAR TOURNAMENT SURFACE ROUND WINNER SCORE/ RESULT TIME 2008 CUNEO CLAY 1r Sorana Cirstea 6-3 4-6 6-3 0m Ranking History TOP RANK YEAR-END YEAR TOP RANK YEAR-END 58 - 2021 35 - 69 86 2020 30 35 72 72 2019 31 46 33 86 2018 27 35 37 37 2017 23 36 81 81 2016 24 24 90 244 2015 61 186 21 93 2014 30 62 21 22 2013 51 51 26 27 2012 120 122 https://dev.saptennis.com/media/mediaportal/#season/2021/events/0406/matches/LS009/apps/post-match-insights/match-notes/snapshots/58b5f… 2/8 26/05/2021 SAP Tennis Analytics 1.4.9 MATCH NOTES INTERNATIONAUX DE STRASBOURG - STRASBOURG, FRANCE 2021-05-23 - 2021-05-29 | $ 235,238 Sorana Shuai Cirstea Zhang Tournament History CURRENT TOURNAMENT CURRENT TOURNAMENT 1r: d. -

Wimbledon: Second Williams Sister Still in Tourney /B1

Wimbledon: Second Williams sister still in tourney /B1 WEDNESDAY TODAY CITRUS COUNTY & next morning HIGH 85 Very windy; showers LOW likely and a slight chance of storms. 74 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JUNE 27, 2012 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOLUME 117 ISSUE 325 NEWS BRIEFS Citrus County Bracing for Debby in state of emergency Due to expected high winds and coastal storm flooding in low-lying areas on the west side of Citrus County, the Board of County Commissioners unanimously voted to de- clare a local State of Emergency for Citrus County. This event declaration will last for seven days. Although no mandatory evacuations have been ordered, emergency man- agement officials are opening a special-needs shelter at the Renais- sance Center in Lecanto at 3630 W. Educational Path, and a pet-friendly/ general population shelter at Lecanto Primary School at 3790 W. Educational Path, Lecanto. Both shelters opened at 7 p.m. Tuesday. More information re- garding shelter openings and evacuations will be activated and distributed through the Citrus County Sheriff’s Office. Citizens may call the Sheriff’s Of- fice Citizen Information Lines at 352-527-2106 or DAVE SIGLER/Chronicle 352-746-5470. Doreen Mylin, owner of Magic Manatee Marina, waits Tuesday night in hopes her husband could move two forklifts away from the rising waters along the Homosassa River. “The ‘no-name’ storm was worst. This will be the second-worst,” Mylin said. —From staff reports Debby’s tropical weather brings flooding to portions of Citrus County INSIDE MIKE WRIGHT The high tide Tuesday night was expected stein said, referring to coastal residents who LOCAL NEWS: Staff Writer to bring 3 to 5 feet additional water to areas have seen water rise steadily since Sunday such as Homosassa and Crystal River that al- when the area was soaked with rain by Debby. -

Proceedings+Of+The+8Th+ Scheduling+And+Planning+

ICAPS 2014 ! ! Proceedings+of+the+8th+ Scheduling+and+Planning+Applications+Workshop+ + Edited+By:+ Gabriella+Cortellessa,+Mark+Giuliano,+Riccardo+Rasconi+and+Neil+Yorke@Smith+ + Portsmouth,*New*Hampshire,*USA*5*June*22,*2014* * Organizing*Committee* Gabriella(Cortellessa! ISTC&CNR,!Italy! Mark(Giuliano( Space!Telescope!Science!Institute,!USA!! Riccardo(Rasconi! ISTC&CNR,!Italy! Neil(Yorke6Smith( American!University!of!Beirut,!Lebanon,!and!University!of!Cambridge,!UK! ! Program*Committee* Laura(Barbulescu,!Carnegie!Mellon!University,!USA!! Anthony(Barrett,!Jet!Propulsion!Laboratory,!USA!! Mark(Boddy,!Adventium,!USA!! Luis(Castillo,!University!of!Granada,!Spain!! Gabriella(Cortellessa,!ISTC&CNR,!Italy! Riccardo(De(Benedictis,!ISTC&CNR,!Italy!! Minh(Do,!SGT!Inc.,!NASA!Ames,!USA!! Simone(Fratini,!ESA&ESOC,!Germany!! Mark(Giuliano,!Space!Telescope!Science!Institute,!USA! Christophe(Guettier,!SAGEM,!France!! Patrik(Haslum,!NICTA,!Australia!! Nicola(Policella,!ESA&ESOC,!Germany!! Riccardo(Rasconi,!ISTC&CNR,!Italy! Bernd(Schattenberg,!University!of!Ulm,!Germany!! Tiago(Vaquero,!University!of!Toronto,!Canada!! Ramiro(Varela,!University!of!Oviedo,!Spain!! Gérard(Verfaillie,!ONERA,!France!! Neil(Yorke6Smith,!American!University!of!Beirut,!Lebanon!and!University!of!Cambridge,!UK! Terry(Zimmerman,!University!of!Washington!–!Bothell,!USA! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Foreword! ! Application!domains!that!entail!planning!and!scheduling!(P&S)!problems!present!a!set!of!compelling!challenges! to!the!AI!planning!and!scheduling!community,!from!modeling!to!technological!to!institutional!issues.!New!real& -

Adelaide International – Day 2 Ranking Points

MATCH NOTES: ADELAIDE INTERNATIONAL ADELAIDE, AUSTRALIA | JANUARY 13-18, 2020 | USD $782,900 PREMIER WTA Website: www.wtatennis.com | @WTA | facebook.com/wta Tournament Website: www.adelaideinternational.com.au | @AdelaideTennis | facebook.com/AdelaideInternationalTennis WTA Communications: Chase Altieri ([email protected]), Ellie Emerson ([email protected]), Adam Lincoln ([email protected]) SAP Tennis Analytics for Media is an online portal that provides real-time data and insights to media during every WTA event and across all devices. Please email [email protected] to request your individual login to grant access to SAP Tennis Analytics for Media. ADELAIDE INTERNATIONAL – DAY 2 [Q] ARINA RODIONOVA (AUS #201) vs. SLOANE STEPHENS (USA #25) First meeting Rodionova was taken to three sets in both her qualifying matches… Stephens fell at opening hurdle last week in Brisbane… Rodionova is one of four Australians in the starting field [1] ASHLEIGH BARTY (AUS #1) vs. ANASTASIA PAVLYUCHENKOVA (RUS #31) Pavlyuchenkova leads 3-2 Barty came from a break down in the third set to triumph when they met at 2018 Wuhan… Pavlyuchenkova bidding for second win over a World No.1… Both players lost early last week [WC] AJLA TOMLJANOVIC (AUS #52) vs. [2] SIMONA HALEP (ROU #4) Halep leads 2-0 Halep won when they met at Roland Garros in 2019… Tomljanovic beat Putintseva in straight sets on Monday… Halep playing first singles match since reuniting with coach Darren Cahill [6/WC] ARYNA SABALENKA (BLR #12) vs. HSIEH SU-WEI (TPE #36)