The Case of Race Classification and Reclassification Under Apartheid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Conscription in South Africa, 1952-1972

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 35, Nr 1, 2007. doi: 10.5787/35-1-29 46 PATRIOTIC DUTY OR RESENTED IMPOSITION? PUBLIC REACTIONS TO MILITARY CONSCRIPTION IN WHITE SOUTH AFRICA, 1952-1972 __________________________________ Graeme Callister Department of History, University of Stellenbosch1 Introduction It is widely known that from the introduction of the Defence Amendment Act of 1967 (Act no. 85 of 1967) until the fall of apartheid in 1994, South Africa had a system of universal national service for white males, and that the men conscripted into the South African Defence Force (SADF) under this system were engaged in conflicts in Namibia, Angola, and later in the townships of South Africa itself. What is widely ignored however, both in academia and in wider society, is that the South African military relied on conscripts, selected through a ballot system, to fill its ranks for some fifteen years before the introduction of universal service. This article intends to redress this scholastic imbalance. The period of universal military service coincides with the period that saw South Africa in the world’s spotlight, when defeating apartheid was the great crusade in which capitalist and communist alike could engage. It is therefore not surprising that the military of that era has also been studied. Post-1967 universal national service in South Africa has received some attention from scholars, and is generally portrayed as a resented imposition at best. Resistance to conscription is widely covered, especially through the 1980s when organisations such as the Conscientious Objectors Support Group (COSG, formed in 1980) and the End Conscription Campaign (ECC, formed in 1983) gave a more public ‘face’ to the anti-conscription movement.2 However, as can be seen from the relatively late 1 I would like to extend my gratitude to Professor Albert Grundlingh of the University of Stellenbosch for his comments and advice on the first draft of this article. -

Reflections on Apartheid in South Africa: Perspectives and an Outlook for the Future

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 415 168 SO 028 325 AUTHOR Warnsley, Johnnye R. TITLE Reflections on Apartheid in South Africa: Perspectives and an Outlook for the Future. A Curriculum Unit. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminar Abroad 1996 (South Africa). INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 77p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *African Studies; *Apartheid; Black Studies; Foreign Countries; Global Education; Instructional Materials; Interdisciplinary Approach; Peace; *Racial Discrimination; *Racial Segregation; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS African National Congress; Mandela (Nelson); *South Africa ABSTRACT This curriculum unit is designed for students to achieve a better understanding of the South African society and the numerous changes that have recently, occurred. The four-week unit can be modified to fit existing classroom needs. The nine lessons include: (1) "A Profile of South Africa"; (2) "South African Society"; (3) "Nelson Mandela: The Rivonia Trial Speech"; (4) "African National Congress Struggle for Justice"; (5) "Laws of South Africa"; (6) "The Pass Laws: How They Impacted the Lives of Black South Africans"; (7) "Homelands: A Key Feature of Apartheid"; (8) "Research Project: The Liberation Movement"; and (9)"A Time Line." Students readings, handouts, discussion questions, maps, and bibliography are included. (EH) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 00 I- 4.1"Reflections on Apartheid in South Africa: Perspectives and an Outlook for the Future" A Curriculum Unit HERE SHALL watr- ALL 5 HALLENTOEQUALARTiii. 41"It AFiacAPLAYiB(D - Wad Lli -WIr_l clal4 I.4.4i-i PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY (4.)L.ct.0-Aou-S TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) Johnnye R. -

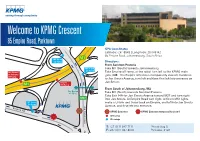

Welcome to KPMG Crescent

Jan Smuts Ave St Andrews M1 Off Ramp Winchester Rd Jan Smuts Off Ramp Welcome to KPMGM27 Crescent M1 North On Ramp De Villiers Graaff Motorway (M1) 85 Empire Road, Parktown St Andrews Rd Albany Rd GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.18548 | Longitude: 28.045142 85 Empire Road, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 B M1 North On Ramp Directions: From Sandton/Pretoria M1 South Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg On Ramp Jan Smuts / Take Empire off ramp, at the robot turn left to the KPMG main St Andrews gate. (NB – the Empire entrance is temporarily closed). Continue Off Ramp to Jan Smuts Avenue, turn left and then first left into entrance on Empire Jan Smuts. M1 Off Ramp From South of JohannesburgWellington Rd /M2 Sky Bridge 4th Floor Take M1 (North) towards Sandton/Pretoria Take Exit 14A for Jan Smuts Avenue toward M27 and turn right M27 into Jan Smuts. At Empire Road turn right, at first traffic lights M1 South make a U-turn and travel back on Empire, and left into Jan Smuts On Ramp M17 Jan Smuts Ave Avenue, and first left into entrance. Empire Rd KPMG Entrance KPMG Entrance temporarily closed Off ramp On ramp T: +27 (0)11 647 7111 Private Bag 9, Jan Jan Smuts Ave F: +27 (0)11 647 8000 Parkview, 2122 E m p ire Rd Welcome to KPMG Wanooka Place St Andrews Rd, Parktown NORTH GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.182416 | Longitude: 28.03816 St Andrews Rd, Parktown, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 St Andrews Off Ramp Jan Smuts Ave Directions: Winchester Rd From Sandton/Pretoria Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg Take St Andrews off ramp, at the robot drive straight to the KPMG Jan Smuts main gate. -

Forced Removal of Population the Apartheid Regime Has Sought to Enforce Strict Territorial Segregation of the Different ‘Population Groups’

residence, commercial activities and industry for members of the White, Coloured and Asian groups (each in separate zones). Based on these group areas are segregated local government structures, and a segregated tricameral parliament with separate White, Coloured and Indian chambers, designed to preserve white political power while extending limited participation in central government to small sections of the Indian and Coloured communities. The majority of the population in South Africa is united in rejecting the segregated political structures of apartheid. Forced Removal of Population The apartheid regime has sought to enforce strict territorial segregation of the different ‘population groups’. People are forcibly evicted from their homes if they are in a zone which the government has asigned to another group. The government speaks, not of forced removal or eviction, but of Relocation and Resettlement. The evictions take place in many different kinds of areas and under different laws. In rural areas people are moved on a number of different pretexts. The places in which they live may be designated Black Spots — these are areas of land occupied and owned by Africans which the government has designated for another group, usually white. The occupiers are moved to a bantustan. Others are moved in the course of Consolidation of the bantustans, as the regime attempts to reduce the number of fragments of land which make up the bantustans. Over a million black tenants have been evicted from white owned farms since the 1960s. Tenants who paid cash rent to the farms were called Squatters, implying they had no right to be on the land. -

Resistance, Language and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North

Masthead Logo Smith ScholarWorks History: Faculty Publications History Summer 2016 The tE ymology of Nigger: Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor Smith College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/hst_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Pryor, Elizabeth Stordeur, "The tE ymology of Nigger: Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North" (2016). History: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/hst_facpubs/4 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] The Etymology of Nigger: Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor Journal of the Early Republic, Volume 36, Number 2, Summer 2016, pp. 203-245 (Article) Published by University of Pennsylvania Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jer.2016.0028 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/620987 Access provided by Smith College Libraries (5 May 2017 18:29 GMT) The Etymology of Nigger Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North ELIZABETH STORDEUR PRYOR In 1837, Hosea Easton, a black minister from Hartford, Connecticut, was one of the earliest black intellectuals to write about the word ‘‘nigger.’’ In several pages, he documented how it was an omni- present refrain in the streets of the antebellum North, used by whites to terrorize ‘‘colored travelers,’’ a term that elite African Americans with the financial ability and personal inclination to travel used to describe themselves. -

The White Opposition Splits

12 THE WHITE OPPOSITION SPLITS STANLEY UYS Political Correspondent of the 'Sunday Times1 THE annual congress of the official South African Parliamentary Opposition or United Party in August last year, on the eve of the Provincial Elections, resulted in the resignation of almost a quarter of its Members of Parliament and the formation of a new white political party—the Progressives. Amidst the exhuma tions and excuses, analyses and adjustments that followed, two highly significant conclusions emerged—the official Parliamentary Opposition has swung substantially to the right, narrowing the already narrow gap between Government and United Party on the doctrines of race rule; and, for the first time in South African history, a substantial white Parliamentary Party with wide, if not dominant, electoral support in many urban areas, had come into existence specifically in order to propagate a more liberal policy in race relations. The origin of the Progressive break must be sought in the right-wing ''rethinking" resulting from the total failure of the United Party to avoid a steady electoral decline during the n years in which it has been in Opposition. In 1948, the Nationalist Party came to power with a majority of fewer than half-a-dozen M.P.s. Today, it has two-thirds of the House of Assembly, partly due to the completely one-sided character of the electoral system (particularly delimitation methods) and partly to the growing numerical superiority of the Afrikaner. It did not take the United Party long to evolve the view that there was no profit in battering its head against a stone wall, and that the only chance of success lay in winning over "moderate'' Nationalist voters. -

Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010

Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010 Julian A Jacobs (8805469) University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie Masters Research Essay in partial fulfillment of Masters of Arts Degree in History November 2010 DECLARATION I declare that „Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010‟ is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. …………………………………… Julian Anthony Jacobs i ABSTRACT This is a study of activists from Manenberg, a township on the Cape Flats, Cape Town, South Africa and how they went about bringing change. It seeks to answer the question, how has activism changed in post-apartheid Manenberg as compared to the 1980s? The study analysed the politics of resistance in Manenberg placing it within the over arching mass defiance campaign in Greater Cape Town at the time and comparing the strategies used to mobilize residents in Manenberg in the 1980s to strategies used in the period of the 2000s. The thesis also focused on several key figures in Manenberg with a view to understanding what local conditions inspired them to activism. The use of biographies brought about a synoptic view into activists lives, their living conditions, their experiences of the apartheid regime, their brutal experience of apartheid and their resistance and strength against a system that was prepared to keep people on the outside. This study found that local living conditions motivated activism and became grounds for mobilising residents to make Manenberg a site of resistance. It was easy to mobilise residents on issues around rent increases, lack of resources, infrastructure and proper housing. -

The Semantics and Pragmatics of Slurs and Thick Terms Bianca Cepollaro

The Semantics and Pragmatics of slurs and thick terms Bianca Cepollaro To cite this version: Bianca Cepollaro. The Semantics and Pragmatics of slurs and thick terms. Philosophy. Uni- versité Paris sciences et lettres; Scuola normale superiore (Pise, Italie), 2017. English. NNT : 2017PSLEE003. tel-01508856 HAL Id: tel-01508856 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01508856 Submitted on 14 Apr 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE DE DOCTORAT de l’Université de recherche Paris Sciences et Lettres PSL Research University Préparée dans le cadre d’une cotutelle entre Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa et École Normale Supérieure, Paris La sémantique et la pragmatique des termes d’offense et des termes éthiques épais Ecole doctorale n°540 ÉCOLE TRANSDISCIPLINAIRE LETTRES/SCIENCES Spécialité Philosophie COMPOSITION DU JURY : Mme. JESHION Robin University of South California, Rapporteur M. VÄYRYNEN Pekka University of Leeds, Rapporteur Mme. BIANCHI Claudia Soutenue par Bianca Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Membre du jury CEPOLLARO Le 20 janvier 2017h Mme. SBISÀ Marina Università degli Studi di Trieste, Membre du jury Dirigée par Pier Marco BERTINETTO et Isidora STOJANOVIC The semantics and pragmatics of slurs and thick terms Bianca Cepollaro Abstract In this thesis I develop a uniform account of slurs and thick terms in terms of presuppositions. -

Hillbilly Heroin(E) Lauren Audrey Tussey [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2015 Hillbilly heroin(e) Lauren Audrey Tussey [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, and the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation Tussey, Lauren Audrey, "Hillbilly heroin(e)" (2015). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 960. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HILLBILLY HEROIN(E) A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Lauren Audrey Tussey Approved by Dr. Rachael Peckham, Committee Chairperson Dr. Carrie Oeding Dr. Cody Lumpkin Marshall University December 2015 ii Lauren Audrey Tussey ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The literary journal Pithead Chapel possesses First Serial Rights and nonexclusive Electronic Archival Rights to “Father’s Fence” as of June 2015. iv DEDICATIONS This work is dedicated to my mother, Laura Tussey, who has always been a brilliant inspiration to me through her strength and wisdom; and to my mentors, Rachael Peckham and A.E. Stringer, who have guided me through my education and provided me with the skills I needed to find my voice. I appreciate you all. v The following manuscript -

Apartheid Laws & Regulations

APARTHEID LAWS & REGULATIONS : INTRODUCED AND RESCINDED A Short Summary The absurdity of apartheid legislation, which incorporated legislation passed by the (minority) white governments prior to 1948, is reflected in the following list . Although the legislation was seemingly passed in the interest of the white minority, to maintain both political and social hegemony, it is obvious that most of the measures carried little or no economic benefit for the ruling class and that its scrapping would be in the interests of the capitalist class as well as the majority of blacks . For blacks the end of apartheid laws meant that the hated pass system was abolished, that the legality of residential apartheid was removed from the statute book and that antu education was formally ended . Nonetheless there was little freedom for the poor to move from their squatter camps or township houses and most children still went to third rate schools with few amenities to assist them . It was only a section of the wealthier blacks and those who ran the political machine that benefited most fully from the changes . The vast majority saw no improvements in their way of life, a matter that is dealt with in this issue of Searchlight South Africa . It is also not insignificant that many measures were repealed before the unbanning of opposition political movements and before negotia- tions got under way. The pressure for change came partly from the activities of the internal resistance movement and the trade unions, from covert discussions between movements that supported the government and the ANC, from the demographic pressure that led to a mass migra- tion to the urban areas and also from the altered relations between the USSR and the west - a change which was interpreted by the govern- ment as removing the communist threat from the region . -

Curren T Anthropology

Forthcoming Current Anthropology Wenner-Gren Symposium Curren Supplementary Issues (in order of appearance) t Human Biology and the Origins of Homo. Susan Antón and Leslie C. Aiello, Anthropolog Current eds. e Anthropology of Potentiality: Exploring the Productivity of the Undened and Its Interplay with Notions of Humanness in New Medical Anthropology Practices. Karen-Sue Taussig and Klaus Hoeyer, eds. y THE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES Previously Published Supplementary Issues April THE BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY OF LIVING HUMAN Working Memory: Beyond Language and Symbolism. omas Wynn and 2 POPULATIONS: WORLD HISTORIES, NATIONAL STYLES, 01 Frederick L. Coolidge, eds. 2 AND INTERNATIONAL NETWORKS Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas. Setha M. Low and Sally GUEST EDITORS: SUSAN LINDEE AND RICARDO VENTURA SANTOS Engle Merry, eds. V The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations olum Corporate Lives: New Perspectives on the Social Life of the Corporate Form. Contexts and Trajectories of Physical Anthropology in Brazil Damani Partridge, Marina Welker, and Rebecca Hardin, eds. e Birth of Physical Anthropology in Late Imperial Portugal 5 Norwegian Physical Anthropology and a Nordic Master Race T. Douglas Price and Ofer 3 e Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas. The Ainu and the Search for the Origins of the Japanese Bar-Yosef, eds. Isolates and Crosses in Human Population Genetics Supplement Practicing Anthropology in the French Colonial Empire, 1880–1960 Physical Anthropology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States Humanizing Evolution Human Population Biology in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century Internationalizing Physical Anthropology 5 Biological Anthropology at the Southern Tip of Africa The Origins of Anthropological Genetics Current Anthropology is sponsored by e Beyond the Cephalic Index Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Anthropology and Personal Genomics Research, a foundation endowed for scientific, Biohistorical Narratives of Racial Difference in the American Negro educational, and charitable purposes. -

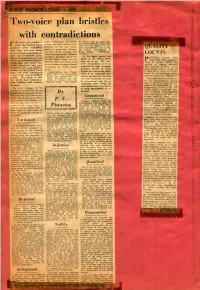

A1132-Ba2-002-Jpeg.Pdf

- ■ m m m Two-voice plan bristles with contradictions N the first two articles I either individuals or racial be shared with all those non- wrote that United Party groups, and apart from a brief Europeans who have shown that I reference to what was clearly they have the capacity to take speakers often contradict joint responsibility with us for each other and even them meant as safeguards between the future development of selves in their statements on the two White sections and South Afriea.” ("Weekblad,” which was made in the "Ordered 1 7 . 3 . 6 1 . ) COUNTS v> their race federation plan. In the tame speech the Advance” pamphlet issued by OLITICAL parties, more | Those contradictions are no leader of the United Party doubt an indication that the Sir De Villiers Graaff on Oc than most other organisa- S tober 25, 1960, I could find little went on to say: "W e want j P! tions of people, reflect the whole plan was rather hur them (the Africans) to be re W , i riedly conceived and pre or no reference to constitutional , quality of human material safeguards in United Party presented by eight European \ j they embody. In other words maturely horn and that the members, elected by those I good people tend to make for f leaders of the United Party policy. Natives who have shown them- ■ | a good party, indifferent j have not even considered Nevertheless the United selves to be responsible citi people for an indifferent party, ï certain vital aspects of their Party has as its main policy plank, the safeguarding of zens of our country." But ham and bad people for a bad party.