Technical Design in UML for Angular Applications and Other Web Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OMG Systems Modeling Language (OMG Sysml™) Tutorial 25 June 2007

OMG Systems Modeling Language (OMG SysML™) Tutorial 25 June 2007 Sanford Friedenthal Alan Moore Rick Steiner (emails included in references at end) Copyright © 2006, 2007 by Object Management Group. Published and used by INCOSE and affiliated societies with permission. Status • Specification status – Adopted by OMG in May ’06 – Finalization Task Force Report in March ’07 – Available Specification v1.0 expected June ‘07 – Revision task force chartered for SysML v1.1 in March ‘07 • This tutorial is based on the OMG SysML adopted specification (ad-06-03-01) and changes proposed by the Finalization Task Force (ptc/07-03-03) • This tutorial, the specifications, papers, and vendor info can be found on the OMG SysML Website at http://www.omgsysml.org/ 7/26/2007 Copyright © 2006,2007 by Object Management Group. 2 Objectives & Intended Audience At the end of this tutorial, you should have an awareness of: • Benefits of model driven approaches for systems engineering • SysML diagrams and language concepts • How to apply SysML as part of a model based SE process • Basic considerations for transitioning to SysML This course is not intended to make you a systems modeler! You must use the language. Intended Audience: • Practicing Systems Engineers interested in system modeling • Software Engineers who want to better understand how to integrate software and system models • Familiarity with UML is not required, but it helps 7/26/2007 Copyright © 2006,2007 by Object Management Group. 3 Topics • Motivation & Background • Diagram Overview and Language Concepts • SysML Modeling as Part of SE Process – Structured Analysis – Distiller Example – OOSEM – Enhanced Security System Example • SysML in a Standards Framework • Transitioning to SysML • Summary 7/26/2007 Copyright © 2006,2007 by Object Management Group. -

VI. the Unified Modeling Language UML Diagrams

Conceptual Modeling CSC2507 VI. The Unified Modeling Language Use Case Diagrams Class Diagrams Attributes, Operations and ConstraintsConstraints Generalization and Aggregation Sequence and Collaboration Diagrams State and Activity Diagrams 2004 John Mylopoulos UML -- 1 Conceptual Modeling CSC2507 UML Diagrams I UML was conceived as a language for modeling software. Since this includes requirements, UML supports world modeling (...at least to some extend). I UML offers a variety of diagrammatic notations for modeling static and dynamic aspects of an application. I The list of notations includes use case diagrams, class diagrams, interaction diagrams -- describe sequences of events, package diagrams, activity diagrams, state diagrams, …more... 2004 John Mylopoulos UML -- 2 Conceptual Modeling CSC2507 Use Case Diagrams I A use case [Jacobson92] represents “typical use scenaria” for an object being modeled. I Modeling objects in terms of use cases is consistent with Cognitive Science theories which claim that every object has obvious suggestive uses (or affordances) because of its shape or other properties. For example, Glass is for looking through (...or breaking) Cardboard is for writing on... Radio buttons are for pushing or turning… Icons are for clicking… Door handles are for pulling, bars are for pushing… I Use cases offer a notation for building a coarse-grain, first sketch model of an object, or a process. 2004 John Mylopoulos UML -- 3 Conceptual Modeling CSC2507 Use Cases for a Meeting Scheduling System Initiator Participant -

APECS: Polychrony Based End-To-End Embedded System Design and Code Synthesis

APECS: Polychrony based End-to-End Embedded System Design and Code Synthesis Matthew E. Anderson Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Engineering Sandeep K. Shukla, Chair Lamine Mili Alireza Haghighat Chao Wang Yi Deng April 3, 2015 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: AADL, CPS, Model-based code synthesis, correct-by-construction code synthesis, Polychrony, code generators, OSATE, Ocarina Copyright 2015, Matthew E. Anderson APECS: Polychrony based End-to-End Embedded System Design and Code Synthesis Matthew E. Anderson (ABSTRACT) The development of high integrity embedded systems remains an arduous and error-prone task, despite the efforts by researchers in inventing tools and techniques for design automa- tion. Much of the problem arises from the fact that the semantics of the modeling languages for the various tools, are often distinct, and the semantics gaps are often filled manually through the engineer's understanding of one model or an abstraction. This provides an op- portunity for bugs to creep in, other than standardising software engineering errors germane to such complex system engineering. Since embedded systems applications such as avionics, automotive, or industrial automation are safety critical, it is very important to invent tools, and methodologies for safe and reliable system design. Much of the tools, and techniques deal with either the design of embedded platforms (hardware, networking, firmware etc), and software stack separately. The problem of the semantic gap between these two, as well as between models of computation used to capture semantics must be solved in order to design safer embedded systems. -

Sysml Distilled: a Brief Guide to the Systems Modeling Language

ptg11539604 Praise for SysML Distilled “In keeping with the outstanding tradition of Addison-Wesley’s techni- cal publications, Lenny Delligatti’s SysML Distilled does not disappoint. Lenny has done a masterful job of capturing the spirit of OMG SysML as a practical, standards-based modeling language to help systems engi- neers address growing system complexity. This book is loaded with matter-of-fact insights, starting with basic MBSE concepts to distin- guishing the subtle differences between use cases and scenarios to illu- mination on namespaces and SysML packages, and even speaks to some of the more esoteric SysML semantics such as token flows.” — Jeff Estefan, Principal Engineer, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory “The power of a modeling language, such as SysML, is that it facilitates communication not only within systems engineering but across disci- plines and across the development life cycle. Many languages have the ptg11539604 potential to increase communication, but without an effective guide, they can fall short of that objective. In SysML Distilled, Lenny Delligatti combines just the right amount of technology with a common-sense approach to utilizing SysML toward achieving that communication. Having worked in systems and software engineering across many do- mains for the last 30 years, and having taught computer languages, UML, and SysML to many organizations and within the college setting, I find Lenny’s book an invaluable resource. He presents the concepts clearly and provides useful and pragmatic examples to get you off the ground quickly and enables you to be an effective modeler.” — Thomas W. Fargnoli, Lead Member of the Engineering Staff, Lockheed Martin “This book provides an excellent introduction to SysML. -

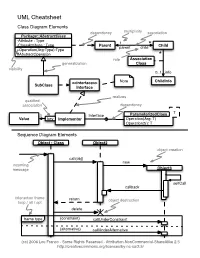

UML Cheatsheet

UML Cheatsheet Class Diagram Elements dependency multiplicity association Package::AbstractClass -Attribute : Type 1 -ClassAttribute : Type Parent Child parent child* +Operation(Arg:Type):Type #AbstractOperation * role Association generalization Class visibility 0..1 info <<interface>> Note ChildInfo SubClass Interface realizes qualified association dependency T 1 Interface ParameterizedClass Value key Implementor Operation(Arg: T) Operation2(): T Sequence Diagram Elements Object : Class Object2 object creation call(obj) new incoming message Object3 selfCall callback interaction frame return object destruction loop / alt / opt delete frame type {constraint} callUnderConstraint {alternative} callUnderAlternative (cc) 2006 Lou Franco - Some Rights Reserved - Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 (cc) 2006 Lou Franco - Some Rights Reserved - Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ Package Diagram Elements dependency Data View Model SQLServer Oracle Object Diagram Elements John : Child name = "John" parent: Parent Mary : Child name = "Mary" Use Case Diagram Elements system boundary actor 1 Library checkout 1 Membership <<include>> Common return start : Date Role Use Case Use Case renewal : Date * LendRecord Role Lendable due : Date <<include>> id 1 returned : Boolean newArrival : Boolean * LendRecord(lendable, member, date) calcDueDate(member): Date isDue() : Boolean Use Case Use Case renew(Date) * Role Book CD 1 Role * Member DVD (cc) 2006 -

What Is Package Diagram? How to Draw Package Diagram?

Visual Paradigm Tutorial What is Package Diagram? How to Draw Package Diagram? What is Package Diagram? How to Draw Package Diagram? Written Date : July 29, 2014 At the beginning of the project, you only have a limited number of diagrams and everything is simple and beautiful. However, when time flies, more and more diagrams have been created and they start to become unmanageable. As a result, your project becomes hard to navigate and diagrams become difficult to locate when you want to review or make changes. How can we fix it up? We can make use of the Package Diagram to organize your diagrams into different packages. This helps you in categorizing your diagrams according to their natures, making them easier to be navigated and located. The Package Diagram also serves as a catalog for you to jump to the diagram that you want to look at. In this tutorial, we will show you how this can be done. Create Packages for your diagrams First, we need to have our packages ready. To create packages: 1. To create a Package Diagram, select Diagram > New from the toolbar. 2. In the New Diagram window, select Package Diagram and click Next. https://www.visual-paradigm.com/tutorials/packagediagram.jsp Page 1 of 11 Visual Paradigm Tutorial What is Package Diagram? How to Draw Package Diagram? 3. Enter Racing Game Packages as diagram name and click OK to confirm. 4. Click the Package button in diagram tool bar, then click on the blank area of the diagram to create the package. 5. Name the package as Race. -

Getting Started with Sysml 3 This Chapter Provides an Introduction to Sysml and Guidance on How to Begin Modeling in Sysml

CHAPTER Getting Started with SysML 3 This chapter provides an introduction to SysML and guidance on how to begin modeling in SysML. The chapter provides a brief overview of SysML, and then introduces a simplified version of the language we refer to as SysML-Lite, along with a simplified example, and tool tips on how to capture the model in a typical modeling tool. This chapter also introduces a simplified model-based systems engineering (MBSE) method that is consistent with the systems engineering process described in Chapter 1, Section 1.2. The chapter finishes by describing some of the challenges involved in learning SysML and MBSE. 3.1 SYSML PURPOSE AND KEY FEATURES SysML1 is a general-purpose graphical modeling language that supports the analysis, specification, design, verification, and validation of complex systems. These systems may include hardware, soft- ware, data, personnel, procedures, facilities, and other elements of man-made and natural systems. The language is intended to help specify and architect systems and specify their components that can then be designed using other domain-specific languages such as UML for software design and VHDL and three-dimensional geometric modeling for hardware design. SysML is intended to facilitate the application of an MBSE approach to create a cohesive and consistent model of the system that yields the benefits described in Chapter 2, Section 2.1.2. SysML can represent the following aspects of systems, components, and other entities: n Structural composition, interconnection, and classification n Function-based, message-based, and state-based behavior n Constraints on the physical and performance properties n Allocations between behavior, structure, and constraints n Requirements and their relationship to other requirements, design elements, and test cases 3.2 SYSML DIAGRAM OVERVIEW SysML includes nine diagrams as shown in the diagram taxonomy in Figure 3.1. -

Standardized Technical Architecture Modeling Conceptual and Design Level

Standardized Technical Architecture Modeling Conceptual and Design Level Version 1.0 March 2007 Copyright 2007 SAP AG. All Rights Reserved No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or for any purpose without the express permission of SAP AG. The information contained herein may be changed without prior notice. Some software products marketed by SAP AG and its distributors contain proprietary software components of other software vendors. Microsoft, Windows, Excel, Outlook, and PowerPoint are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. IBM, DB2, DB2 Universal Database, OS/2, Parallel Sysplex, MVS/ESA, AIX, S/390, AS/400, OS/390, OS/400, iSeries, pSeries, xSeries, zSeries, System i, System i5, System p, System p5, System x, System z, System z9, z/OS, AFP, Intelligent Miner, WebSphere, Netfinity, Tivoli, Informix, i5/OS, POWER, POWER5, POWER5+, OpenPower and PowerPC are trademarks or registered trademarks of IBM Corporation. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Acrobat, PostScript, and Reader are either trademarks or registered trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. Oracle is a registered trademark of Oracle Corporation. UNIX, X/Open, OSF/1, and Motif are registered trademarks of the Open Group. Citrix, ICA, Program Neighborhood, MetaFrame, WinFrame, VideoFrame, and MultiWin are trademarks or registered trademarks of Citrix Systems, Inc. HTML, XML, XHTML and W3C are trademarks or registered trademarks of W3C®, World Wide Web Consortium, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Java is a registered trademark of Sun Microsystems, Inc. JavaScript is a registered trademark of Sun Microsystems, Inc., used under license for technology invented and implemented by Netscape. -

UNIT 1 UML DIAGRAMS Introduction to OOAD – Unified Process

VEL TECH HIGH TECH Dr. RANGARAJAN Dr. SAKUNTHALA ENGINEERING COLLEGE UNIT 1 UML DIAGRAMS Introduction to OOAD – Unified Process - UML diagrams – Use Case – Class Diagrams– Interaction Diagrams – State Diagrams – Activity Diagrams – Package, component and Deployment Diagrams. INTRODUCTION TO OOAD ANALYSIS Analysis is a creative activity or an investigation of the problem and requirements. Eg. To develop a Banking system Analysis: How the system will be used? Who are the users? What are its functionalities? DESIGN Design is to provide a conceptual solution that satisfies the requirements of a given problem. Eg. For a Book Bank System Design: Bank(Bank name, No of Members, Address) Student(Membership No,Name,Book Name, Amount Paid) OBJECT ORIENTED ANALYSIS (OOA) Object Oriented Analysis is a process of identifying classes that plays an important role in achieving system goals and requirements. Eg. For a Book Bank System, Classes or Objects identified are Book-details, Student-details, Membership-Details. OBJECT ORIENTED DESIGN (OOD) Object Oriented Design is to design the classes identified during analysis phase and to provide the relationship that exists between them that satisfies the requirements. Eg. Book Bank System Class name Book-Bank (Book-Name, No-of-Members, Address) Student (Name, Membership No, Amount-Paid) OBJECT ORIENTED ANALYSIS AND DESIGN (OOAD) • OOAD is a Software Engineering approach that models an application by a set of Software Development Activities. YEAR/SEM: III/V CS6502-OOAD Page 1 VEL TECH HIGH TECH Dr. RANGARAJAN Dr. SAKUNTHALA ENGINEERING COLLEGE • OOAD emphasis on identifying, describing and defining the software objects and shows how they collaborate with one another to fulfill the requirements by applying the object oriented paradigm and visual modeling throughout the development life cycles. -

Fakulta Informatiky UML Modeling Tools for Blind People Bakalářská

Masarykova univerzita Fakulta informatiky UML modeling tools for blind people Bakalářská práce Lukáš Tyrychtr 2017 MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta informatiky ZADÁNÍ BAKALÁŘSKÉ PRÁCE Student: Lukáš Tyrychtr Program: Aplikovaná informatika Obor: Aplikovaná informatika Specializace: Bez specializace Garant oboru: prof. RNDr. Jiří Barnat, Ph.D. Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Dalibor Toth Katedra: Katedra počítačových systémů a komunikací Název práce: Nástroje pro UML modelování pro nevidomé Název práce anglicky: UML modeling tools for blind people Zadání: The thesis will focus on software engineering modeling tools for blind people, mainly at com•monly used models -UML and ERD (Plant UML, bachelor thesis of Bc. Mikulášek -Models of Structured Analysis for Blind Persons -2009). Student will evaluate identified tools and he will also try to contact another similar centers which cooperate in this domain (e.g. Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Tsukuba University of Technology). The thesis will also contain Plant UML tool outputs evaluation in three categories -students of Software engineering at Faculty of Informatics, MU, Brno; lecturers of the same course; person without UML knowledge (e.g. customer) The thesis will contain short summary (2 standardized pages) of results in English (in case it will not be written in English). Literatura: ARLOW, Jim a Ila NEUSTADT. UML a unifikovaný proces vývoje aplikací : průvodce analýzou a návrhem objektově orientovaného softwaru. Brno: Computer Press, 2003. xiii, 387. ISBN 807226947X. FOWLER, Martin a Kendall SCOTT. UML distilled : a brief guide to the standard object mode•ling language. 2nd ed. Boston: Addison-Wesley, 2000. xix, 186 s. ISBN 0-201-65783-X. Zadání bylo schváleno prostřednictvím IS MU. Prohlašuji, že tato práce je mým původním autorským dílem, které jsem vypracoval(a) samostatně. -

UML Package Diagrams

UML Package Diagrams © 2008 Haim Michael. All Rights Reserved. Introduction The UML Package Diagram presents separated groups of elements. Nearly all UML elements can be grouped into packages. Each package has a separated name space. Referring an element that belongs to a specific package from outside of that package must include the package name preceding the element name we try to refer. © 2008 Haim Michael. All Rights Reserved. Introduction Technically we can use the package construct to organize any type of UML elements. The package construct is usually used to organize classes in the following cases: Classes that belong to the same framework will be placed in the same package. Classes in the same inheritance hierarchy usually belong to the same package. Classes that have the aggregation / composition relationship with each other usually belong to the same package. © 2008 Haim Michael. All Rights Reserved. Package Representation Depicting a package is done using a rectangle that has a tab attached to its top left. © 2008 Haim Michael. All Rights Reserved. Package Representation Within the package we can draw the elements it includes. When doing so, it is possible to write the package name within the package top left tab. © 2008 Haim Michael. All Rights Reserved. Package Representation Alternatively, it is possible to draw each one of the elements outside of the package area and connect each one of them with the package using a solid line and a small circle with a plus sign in it at the end nearest the package. © 2008 Haim Michael. All Rights Reserved. Package Representation © 2008 Haim Michael. -

Tutorial Exercise 4 Answer

Information System Design (U08182) Tutorial Exercise 4 Answer 1. List the different categories of software that may be used in developing a system. CASE tools; compilers, interpreters and run-time support; visual editors; integrated development environments; class browsers; component managers; DBMS; CORBA; testing tools; conversion tools; documentation generators; configuration management systems; debuggers. 2. What packages (not the UML package concept) have you used and what categories do they fall into? The answer to this will depend on the individual. Examples would be: Rational Rose – CASE tool; Java – compiler with run-time support; JBuilder – visual editor/IDE; Microsoft Developer’s Studio – IDE; Oracle – DBMS; VisiBroker – CORBA ORB; TestScope – testing tool; ClearCase – configuration mangement tool; gdb – debugger. 3. Define what is meant by a component. A physical element of a system, usually a file of some sort. can be a source file, used in producing the software for the system, or an element of the runtime system 4. Define what is meant by a node. Processor in the implementation of a system, shown in a deployment diagram. 5. What is a notation for a component? U08182 @Peter Lo 2010 1 6. What is a notation for a node? 7. What are the main purposes of using component diagrams? Model physical software components and the relationships between them; Model source code and relationships between files; Model the structure of releases of software; Specify the files that are compiled into an executable. 8. What are the main purposes of using deployment diagrams? Model physical hardware elements and the communication paths between them; Plan the architecture of the system; Document the deployment of software components on hardware nodes.