The Hardcore Continuum Debate SIMON REYNOLDS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nick Cage Direction

craft production just because of what it does with sampling technology and that alone. It’s got quite a conservative form and quite a pop form as well just at the moment, in terms of the clarity of the sonics. When those elements are added to hip-hop tracks it must be difficult to make the vocal stand out. The biggest challenge is always getting the vocal heard on top of the track — the curse of the underground is an ill-defined vocal. When I went to bigger studios and used 1176s and LA2s it was a revelation, chucking one of them on gets the vocal up a bit. That’s how we were able to blag our way through Dizzee’s first album. What do you use in Dizzee’s vocal chain? With the budget we were on when I did Boy In Da Corner I used a Neumann TLM103B. When I bought it, £500 seemed a hell of a lot of money for a microphone. Then it goes to my Drawmer 1960 — I exchanged a couple of my keyboards for that. Certainly with Showtime, the new desk improved the vocal sound. It would be interesting to just step the gear up a notch, now we have the deal with XL, and see what happens. Do you have a label deal for Dirty Stank records with XL? I Love You came out first on Dirty Stank on the underground, plus other tunes like Ho and some beats. XL has licensed the albums from Dirty Stank so it’s not a true label deal in that sense, although with our first signings, it’s starting to move in that Nick Cage direction. -

Daft Punk, La Toile Et Le Disco: Revival Culturel a L'heure Du Numerique

Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco: Revival culturel a l’heure du numerique Philippe Poirrier To cite this version: Philippe Poirrier. Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco: Revival culturel a l’heure du numerique. French Cultural Studies, SAGE Publications, 2015, 26 (3), pp.368-381. 10.1177/0957155815587245. halshs- 01232799 HAL Id: halshs-01232799 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01232799 Submitted on 24 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. © Philippe Poirrier, « Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco. Revival culturel à l’heure du numérique », French Cultural Studies, août 2015, n° 26-3, p. 368-381. Daft Punk, la Toile et le disco Revival culturel à l’heure du numérique PHILIPPE POIRRIER Université de Bourgogne 26 janvier 2014, Los Angeles, 56e cérémonie des Grammy Awards : le duo français de musique électronique Daft Punk remporte cinq récompenses, dont celle de meilleur album de l’année pour Random Access Memories, et celle de meilleur enregistrement pour leur single Get Lucky ; leur prestation live, la première depuis la sortie de l’album, avec le concours de Stevie Wonder, transforme le Staples Center, le temps du titre Get Lucky, en discothèque. -

L'hantologie Résiduelle, L'hantologie Brute, L'hantologie Traumatique*

Playlist Society Un dossier d’Ulrich et de Benjamin Fogel V3.00 – Octobre 2013 L’hantologie Trouver dans notre présent les traces du passé pour mieux comprendre notre futur Sommaire #1 : Une introduction à l’hantologie #2 : L’hantologie brute #3 : L’hantologie résiduelle #4 : L’hantologie traumatique #5 : Portrait de l’artiste hantologique : James Leyland Kirby #6 : Une ouverture (John Foxx et Public Service Broadcasting) L’hantologie - Page | 1 - Playlist Society #1 : Une introduction à l’hantologie Par Ulrich abord en 2005, puis essentiellement en 2006, l’hantologie a fait son D’ apparition en tant que courant artistique avec un impact particulièrement marqué au niveau de la sphère musicale. Évoquée pour la première fois par le blogueur K-Punk, puis reprit par Simon Reynolds après que l’idée ait été relancée par Mike Powell, l’hantologie s’est imposée comme le meilleur terme pour définir cette nouvelle forme de musique qui émergeait en Angleterre et aux Etats-Unis. A l’époque, cette nouvelle forme, dont on avait encore du mal à cerner les contours, tirait son existence des liens qu’on pouvait tisser entre les univers de trois artistes : Julian House (The Focus Group / fondateur du label Ghost Box), The Caretaker et Ariel Pink. C’est en réfléchissant sur les dénominateurs communs, et avec l’aide notamment de Adam Harper et Ken Hollings, qu’ont commencé à se structurer les réflexions sur le thème. Au départ, il s’agissait juste de chansons qui déclenchaient des sentiments similaires. De la nostalgie qu’on arrive pas bien à identifier, l’impression étrange d’entendre une musique d’un autre monde nous parler à travers le tube cathodique, la perception bizarre d’être transporté à la fois dans un passé révolu et dans un futur qui n’est pas le nôtre, voilà les similitudes qu’on pouvait identifier au sein des morceaux des trois artistes précités. -

Ebook Download This Is Grime Ebook, Epub

THIS IS GRIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hattie Collins | 320 pages | 04 Apr 2017 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781473639270 | English | London, United Kingdom This Is Grime PDF Book The grime scene has been rapidly expanding over the last couple of years having emerged in the early s in London, with current grime artists racking up millions of views for their quick-witted and contentious tracks online and filling out shows across the country. Sign up to our weekly e- newsletter Email address Sign up. The "Daily" is a reference to the fact that the outlet originally intended to release grime related content every single day. Norway adjusts Covid vaccine advice for doctors after admitting they 'cannot rule out' side effects from the Most Popular. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Definition of grime. This site uses cookies. It's all fun and games until someone beats your h Views Read Edit View history. During the hearing, David Purnell, defending, described Mondo as a talented musician and sportsman who had been capped 10 times representing his country in six-a-side football. Fernie, aka Golden Mirror Fortunes, is a gay Latinx Catholic brujx witch — a combo that is sure to resonate…. Scalise calls for House to hail Capitol Police officers. Drill music, with its slower trap beats, is having a moment. Accessed 16 Jan. This Is Grime. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More On: penn station. Police are scrambling to recover , pieces of information which were WIPED from records in blunder An unwillingness to be chained to mass-produced labels and an unwavering honesty mean that grime is starting a new movement of backlash to the oppressive systems of contemporary society through home-made beats and backing tracks and enraged lyrics. -

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018 Rebellion, genre, drugs, freedom, unity, sex, technology, place, community …………………. Disco • Disco marked the dawn of dance-based popular music. • Growing out of the increasingly groove-oriented sound of early '70s and funk, disco emphasized the beat above anything else, even the singer and the song. • Disco was named after discotheques, clubs that played nothing but music for dancing. • Most of the discotheques were gay clubs in New York • The seventies witnessed the flowering of gay clubbing, especially in New York. For the gay community in this decade, clubbing became 'a religion, a release, a way of life'. The camp, glam impulses behind the upsurge in gay clubbing influenced the image of disco in the mid-Seventies so much that it was often perceived as the preserve of three constituencies - blacks, gays and working-class women - all of whom were even less well represented in the upper echelons of rock criticism than they were in society at large. • Before the word disco existed, the phrase discotheque records was used to denote music played in New York private rent or after hours parties like the Loft and Better Days. The records played there were a mixture of funk, soul and European imports. These "proto disco" records are the same kind of records that were played by Kool Herc on the early hip hop scene. - STARS and CLUBS • Larry Levan was the first DJ-star and stands at the crossroads of disco, house and garage. He was the legendary DJ who for more than 10 years held court at the New York night club Paradise Garage. -

Calliope Writing and Linguistics, Department Of

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Calliope Writing and Linguistics, Department of 2007 Calliope Armstrong Atlantic State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/calliope Part of the Art and Design Commons, Creative Writing Commons, and the Photography Commons This magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Writing and Linguistics, Department of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Calliope by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J alliope 2007 Armstrong Atlantic State University Volume XXIII taff Editor Stephanie Roberts Art Editor Allison Walden Poetry and Fiction Staff Erin Christian Britney Compton Emily Mixon Joe O'Connor Art Staff Amanda Altenauer Tyler Jordan Faculty Advisor Dr. Christopher Baker Calliope is published annually by and for the students of Armstrong Atlantic State University. The Student Government Association of AASU provides funding for each publication. Student submissions are collected dirough the fall semester for the following year's publication. All submissions are read and chosen through an anony- mous process to ensure equal opportunity for every entrant. The Lillian Spencer Awards are presented for outstandmg submissions in fiction, poetry and art. The recipients of this award are chosen by the staff from the student submissions received that year. Calliope 2007 submission guidelines: Regardless of medium, each entrant is limited to five submissions. Each entry must have a completed submission form. To ensure anonymity during the selection process, the Calliope staff asks that you not include your name or any identification on your submitted work. -

Grime + Gentrification

GRIME + GENTRIFICATION In London the streets have a voice, multiple actually, afro beats, drill, Lily Allen, the sounds of the city are just as diverse but unapologetically London as the people who live here, but my sound runs at 140 bpm. When I close my eyes and imagine London I see tower blocks, the concrete isn’t harsh, it’s warm from the sun bouncing off it, almost comforting, council estates are a community, I hear grime, it’s not the prettiest of sounds but when you’ve been raised on it, it’s home. “Grime is not garage Grime is not jungle Grime is not hip-hop and Grime is not ragga. Grime is a mix between all of these with strong, hard hitting lyrics. It's the inner city music scene of London. And is also a lot to do with representing the place you live or have grown up in.” - Olly Thakes, Urban Dictionary Or at least that’s what Urban Dictionary user Olly Thake had to say on the matter back in 2006, and honestly, I couldn’t have put it better myself. Although I personally trust a geezer off of Urban Dictionary more than an out of touch journalist or Good Morning Britain to define what grime is, I understand that Urban Dictionary may not be the most reliable source due to its liberal attitude to users uploading their own definitions with very little screening and that Mr Thake’s definition may also leave you with more questions than answers about what grime actually is and how it came to be. -

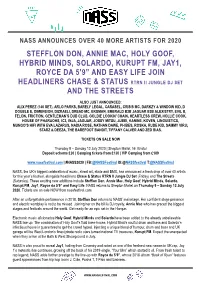

Stefflon Don, Annie Mac, Holy Goof, Hybrid Minds, Solardo

NASS ANNOUNCES OVER 40 MORE ARTISTS FOR 2020 STEFFLON DON, ANNIE MAC, HOLY GOOF, HYBRID MINDS, SOLARDO, KURUPT FM, JAY1, ROYCE DA 5’9” AND EASY LIFE JOIN HEADLINERS CHASE & STATUS RTRN II JUNGLE DJ SET AND THE STREETS ALSO JUST ANNOUNCED: ALIX PEREZ (140 SET), ARLO PARKS, BARELY LEGAL, CARASEL, CRISIS MC, DARKZY & WINDOW KID, D DOUBLE E, DIMENSION, DIZRAELI, DREAD MC, EKSMAN, EMERALD B2B JAGUAR B2B ALEXISTRY, EVIL B, FELON, FRICTION, GENTLEMAN’S DUB CLUB, GOLDIE LOOKIN’ CHAIN, HEARTLESS CREW, HOLLIE COOK, HOUSE OF PHARAOHS, IC3, INJA, JAGUAR, JOSSY MITSU, JUBEI, KANINE, KOVEN, LINGUISTICS, MUNGO’S HIFI WITH EVA LAZARUS, NADIA ROSE, NATHAN DAWE, PHIBES, ROSKA, RUDE KID, SAMMY VIRJI, STARZ & DEEZA, THE BAREFOOT BANDIT, TIFFANY CALVER AND ZED BIAS. TICKETS ON SALE NOW Thursday 9 – Sunday 12 July 2020 | Shepton Mallet, Nr. Bristol Deposit scheme £30 | Camping tickets from £130 | VIP Camping from £189 www.nassfestival.com | #NASS2020 | FB:@NASSFestival IG:@NASSfestival T:@NASSfestival NASS, the UK's biggest celebration of music, street art, skate and BMX, has announced a fresh drop of over 40 artists for this year’s festival, alongside headliners Chase & Status RTRN II Jungle DJ Set (Friday) and The Streets (Saturday). These exciting new additions include Stefflon Don, Annie Mac, Holy Goof, Hybrid Minds, Solardo, Kurupt FM, Jay1, Royce da 5’9” and Easy Life. NASS returns to Shepton Mallet on Thursday 9 – Sunday 12 July 2020. Tickets are on sale NOW from nassfestival.com After an unforgettable performance in 2018, Stefflon Don returns to NASS’ mainstage. Her confident stage presence and electric wordplay is not to be missed. -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

Le Premier Film Documentaire Sur Daft Punk, L'épopée Du Duo Le Plus Secret Du Monde, Avec La Participation Exceptionnelle De Leurs Proches Collaborateurs Et Amis

©Peter Lindbergh LE PREMIER FILM DOCUMENTAIRE SUR DAFT PUNK, L'ÉPOPÉE DU DUO LE PLUS SECRET DU MONDE, AVEC LA PARTICIPATION EXCEPTIONNELLE DE LEURS PROCHES COLLABORATEURS ET AMIS. PREMIÈRE MONDIALE : ÉDITION COLLECTOR DIGIBOOK (DVD ET BLU-RAY™) LE 24 NOVEMBRE #DaftPunkUnchained 2015 : LES 20 ANS DE DAFT PUNK Synopsis DAFT PUNK UNCHAINED réalisé par Hervé Martin Delpierre et co-écrit avec Marina Rozenman est le premier film indépendant qui révèle un Lévy ©Philippe phénomène de société sans précédent dans l'univers de la pop culture depuis 20 ans : DAFT PUNK. Entre fiction et réalité, magie et secrets, théâtralité et humilité, les deux Français Thomas Bengalter et Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo ont créé un univers artistique unique. Tout au long de leur carrière, ils ont choisi de maitriser sans relâche chaque maillon de leur chaîne créative. Le film met en lumière les moments clefs de leur histoire, depuis leur premier groupe de lycée à Paris jusqu'à leur triomphe à Los Angeles, où ils ont remporté cinq Grammy Awards pour leur album Random Access Memories en 2014. A travers leur posture - à contre-courant de notre société du paraître - les DAFT PUNK nous interrogent sur la quête d'indépendance et de liberté de deux créateurs, et sur notre propre rapport à l'image, aux médias, et à la célébrité. A l'heure de la mondialisation et de l'explosion des réseaux sociaux, ils refusent d'afficher leur vrai visage et orchestrent avec précision chacune de leurs apparitions en robots. Produit par BBC Wordwide France, DAFT PUNK UNCHAINED a nécessité deux ans de production. -

Collective Community Chicago Who We Are

Collective Community Chicago Who We Are .. Them Flavors connects curious and open mined creatures with new and progressive forms of art, music, and creation - Giving individuals an inviting environment to reflect, examine and grow one’s perspectives and personalities. … What we do them Flavors is a full-production event collective, both producing and promoting on the rise musicians and artists with club nights, underground parties, record releases, and community involvement. ’ve Been .. Where We As a Chicago-based collective, we pride ourselves on what motivates and moves our fellow beings in the midwest region, but are also mindful of the art and movements of other regions of the great planet we all share as one. Chicago Them flavors were early responders to the footwork movement - the offspring of the native genre, juke. we stay rooted in chicago house music and celebrate its legacy in almost every Event we promote. Detroit we pay homage to our sister, Detroit often with promoting techno music and underground parties. In May 2016, we collaborated with Detroit-local hip hop promoters 777 Renegade , and paired their programming with a bit of chicago footwork, Producing a cross-region and cross - genre function. Texas Marfa, Frontiers red bull Each guest was a result of a thoughtful and hand picked curation process led by t he team at Red Bull to identify those powerful agents of change who are emerging as the disruptors and innovators in their respective cities. Each day was a series of conversations with sciences, academics, and professionals in a variety of disciplines to push innovation and creative thinking, wth the goal of catalyzing new ideas and opportunities in nightlife. -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine