Architecture of the Modern Movement in Tucson, 1945-1975 (DRAFT)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston the Story of How One of the Oldest American Cities Became the Epicenter of Concrete Modernist Architecture

Media Contact: Dan Scheffey Ellen Rubin [email protected] [email protected] (212) 979-0058 (212) 909-2625 HEROIC: CONCRETE ARCHITECTURE AND THE NEW BOSTON THE STORY OF HOW ONE OF THE OLDEST AMERICAN CITIES BECAME THE EPICENTER OF CONCRETE MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE As a worldwide phenomenon, concrete modernism represents one of the major architectural movements of the postwar years, but in Boston it was more transformative across civic, cultural, and academic projects than in any other major city in the United States. Concrete provided an important set of architectural opportunities and challenges for the design community, which fully explored the material’s structural and sculptural qualities. From 1960 to 1976, concrete was used by some of the world's most influential architects in the transformation of Boston including Marcel Breuer, Eduardo Catalano, Henry N. Cobb, Araldo Cossutta, Kallmann and McKinnell, Le Corbusier, I. M. Pei, Paul Rudolph, Josep Lluís Sert, and The Architects Collaborative—creating a vision for the city’s widespread revitalization under the banner of the “New Boston.” Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston presents the historical context and new critical profiles of the buildings that defined Boston during this remarkable period, showing the city as a laboratory for refined experiments in concrete and new strategies in urban planning. Heroic further adds to our understanding of the movement’s broader implications through essays by noted historians and interviews with several key practitioners of HEROIC: Concrete Architecture the time: Peter Chermayeff, Henry N. Cobb, Araldo Cossutta, Michael and the New Boston McKinnell, Tician Papachristou, Tad Stahl, and Mary Otis Stevens. -

100709 WBB MG Text.Id2

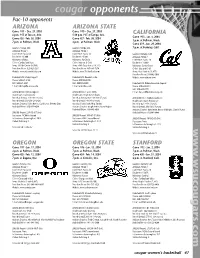

cougar opponents Pac-10 opponents ARIZONA ARIZONA STATE Game #11 – Dec. 29, 2003 Game #10 – Dec. 27, 2003 6 p.m. PST at Tucson, Ariz. 5:30 p.m. PST at Tempe, Ariz. CALIFORNIA Game #13 - Jan. 4, 2004 Game #26 - Feb. 26, 2004 Game #27 - Feb. 28, 2004 1 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. 7 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. 2 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. Game #19 – Jan. 29, 2004 Location: Tucson, Ariz. Location: Tempe, Ariz. 7 p.m. at Berkeley, Calif. Affiliation: NCAA 1 Affiliation: NCAA 1 Conference: Pacific-10 Conference: Pacific-10 Location: Berkeley, Calif. Enrollment: 35,000 Enrollment: 45,693 Affiliation: NCAA 1 Nickname: Wildcats Nickname: Sun Devils Conference: Pacific-10 Colors: Cardinal and Navy Colors: Maroon & Gold Enrollment: 33,000 Arena: McKale Center (14,545) Arena: Wells Fargo Arena (14,141) Nickname: Golden Bears Press Row Phone: 520-621-5291 Press Row Phone: 480-965-7274 Colors: Blue and Gold Website: www.arizonaathletics.com Website: www.TheSunDevils.com Arena: Haas Pavilion (11,877) Press Row Phone: 510-642-3098 Basketball SID: Mindy Claggett Basketball SID: Rhonda Lundin Website: www.calbears.com Phone: 520-621-4163 Phone: 480-965-9780 FAX: 520-621-2681 FAX: 480-965-5408 Basketball SID: Debbie Rosenfeld-Caparaz E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 510-642-3611 FAX: 510-643-7778 Athletic Director: Jim Livengood Athletic Director: Gene Smith E-mail: [email protected] Head Coach: Joan Bonvicini Head Coach: Charli Turner Thorne Record at Arizona: 214-139 (12 years) Record at Arizona State: 106-100 (7 years) Athletic -

2017 Opponents

2017 Opponents PortlaNnIKd ES tIantveit Taotiuornnaal ment Northwestern State Seton Hall Oklahoma Aug. 25, 3:30 p.m., Norman, Okla. Aug. 26, 9 a.m., Norman, Okla. Aug. 26, 6 p.m., Norman, Okla. Location ..............................Natchitoches, La. Location ...........................South Orange, N.J. Location ..................................Norman, Okla. Founded .................................................1884 Founded .................................................1856 Founded .................................................1890 Enrollment .............................................9,819 Enrollment .............................................9,700 Enrollment ...........................................31,250 Nickname .................................Lady Demons Nickname ............................................Pirates Nickname ..........................................Sooners Colors .........................Purple, White, Orange Colors ....................................Blue and White Colors ............................Crimson and Cream Conference ....................................Southland Conference .......................................Big East Conference ..........................................Big 12 Arena (Capacity) ....Prather Coliseum (3,900) Arena (Capacity) ..Walsh Gymnasium (2,600) Arena (Capacity) ......McCasland Field House President .............................Dr. Chris Maggio President ...................Mary Meehan (interim) (5,000) Athletics Director .........................Greg Burke Director -

Washington State

WASHINGTON STATE Women’s Basketball Washington State Athletic Media Relations • Bohler Addition 195 • Pullman, WA 99164 • (509) 335-2684 Jason Krump (Interim Women’s Basketball) - Office 509.335.8843 • [email protected] Bill Stevens, Director - Office: 509.335.4294 • Email: [email protected] Assistant Directors: Linda Chalich ([email protected]) • Craig Lawson ([email protected]) • Jessica Schmick ([email protected]) WSU Schedule Time (PT)/Result Cougars End Regular Season at USC and No. 9 UCLA 11/7 Lewis-Clark State (Exh.) W - 64-63 11/12 at Saint Mary’s L - 73-69 11/14 at UC Davis L - 77-38 11/18 at Portland L - 91-80 11/22 vs. No. 21 Nebraska L - 87-79 Waikiki Beach Marriott Rainbow Wahine Showdown Washington State Cougars (8-20, 6-10) 11/26 vs. No. 14 North Carolina L - 93-55 11/27 vs. Long Beach State W - 87-63 at USC 11/28 vs. Gonzaga L - 67-65 March 3 • Los Angeles, Calif. • 7 p.m. 12/5 vs. Nevada W - 67-54 12/7 vs. South Dakota St. L - 72-61 Cougars begin L.A. trip at USC 12/11 at Gonzaga L - 93-75 12/18 at Wyoming L - 63-43 at No. 9 UCLA 12/21 at San Diego State L - 66-57 12/31 vs. USC L - 72-57 March 5 • Los Angeles, Calif. • 2 p.m. 1/2 vs. No. 8 UCLA L - 80-55 1/6 at Oregon L - 77-72 Cougars face sixth ranked opponent of season 1/8 at Oregon State W - 58-50 1/14 vs. -

Doing Business Search - People

Doing Business Search - People MOCS PEOPLE ID ORGANIZATION NAME 50136 CASTLE SOFTWARE INC 158890 J2 147-07 94TH AVENUE LI LLC 160281 SDF67 SPRINGFIELD BLVD OWNER LLC 129906 E-J ELECTRIC INSTALLATION CO. 63414 NEOPOST USA INC 56283 MAKE THE ROAD NEW YORK 53828 BOSTON TRUST & INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT COMPANY 89181 FALCON BUILDER INC 105272 STERLING INFOSYSTEMS INC 107736 SIEGEL & STOCKMAN 160919 UTECH PRODUCTS INC 49631 LIRO GIS INC. 12881 THE GORDIAN GROUP INC. 64818 ZUCKER'S GIFTS INC 52185 JAMAICA CENTER FOR ARTS & LEARNING INC 146694 GOOD SHEPHERD SERVICES 156009 ATOMS INC. 116226 THE MENTAL HEALTH ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK CITY INC. 150172 SOSA USA LLC Page 1 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People PERSON FIRST NAME PERSON MIDDLE NAME SCOTT FRANK C NATALIE DEBORAH L LUCIA B MEHMET ANDREW PHILIPPE J JAMES J MICHAEL HARRY H MARVIN CATHY HUIYING RACHEL SIDRA SUSAN UZI B Page 2 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People PERSON LAST NAME PERSON_NAME_SUFFIX FISCHER PRG NATIONAL URBAN FUNDS LLC SULLIVAN DEBT FUND HLDINGS LLC LAMBRAIA ADAIR AXT SANTINI PALAOGLU REIBEN DALLACORTE COSTANZO BAILEY MELLON STERNBERG HUNG KITAY QASIM SHANKLIN SCHEFFER Page 3 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People RELATIONSHIP TYPE CODE MCT EWN EWN MCT MCT CFO OWN CFO CFO CEO MCT MCT MCT CEO CEO MCT COO COO CEO Page 4 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People DOING BUSINESS START DATE 09/21/0016 11/20/0019 01/14/0020 03/10/0016 08/08/0008 04/03/0021 11/19/0008 06/02/0014 09/02/0016 03/03/0013 04/03/0021 06/02/0018 08/02/0008 12/05/0008 04/14/0015 02/22/0018 06/05/0019 03/08/0014 01/03/0020 Page 5 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People DOING BUSINESS END DATE Page 6 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People 65572 RUSSELL TRUST COMPANY 53596 MOHAWK LTD 68208 ST ANN'S ABH OWNER LLC 136274 NEW YORK CITY CENTER INC. -

E N G L I S H

Matura Examination 2017 E N G L I S H Advance Information The written Matura examination in English consists of four main sections (total 90 credits in sections I-III): Section I: Listening (credits: 14) Multiple choice and questions Section II: Reading Comprehension (credits: 20) 1. Short answer questions Section III: Use of English (credits: 56) 1. Synonyms 2. Antonyms 3. Word Formation 4. Sentence Transformation 5. Open Cloze Section IV: Writing, approx. 400 words (the mark achieved in this part will make up 50% of the overall mark) Time management: the total time is 240 minutes. We recommend you spend 120 minutes on sections I-III, and 120 minutes on section IV. Write legibly and unambiguously. Spelling is important in all parts of the examination. Use of dictionary: You will be allowed to use a monolingual dictionary after handing in sections I-III. The examination is based on Morgan Meis’s article “Frank Lloyd Wright Tried to Solve the City”, published in the “Critics” section of the May 22, 2014 issue of The New Yorker magazine. Frank Lloyd Wright Tried to Solve the City by MORGAN MEIS In: The New Yorker, May 22, 2014 Frank Lloyd Wright1 hated cities. He thought that they were cramped and crowded, stupidly designed, or, more often, built without any sense of design at all. He once wrote, “To look at the 5 plan of a great City is 5 to look at something like the cross-section of a fibrous tumor.” Wright was always looking for a way to cure the cancer of the city. -

Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria: Stage One

Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria: Stage One Volume 1: Contextual Overview, Methodology, Lists & Appendices Prepared for Heritage Victoria October 2008 This report has been undertaken in accordance with the principles of the Burra Charter adopted by ICOMOS Australia This document has been completed by David Wixted, Suzanne Zahra and Simon Reeves © heritage ALLIANCE 2008 Contents 1.0 Introduction................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Context ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Project Brief .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................... 6 2.0 Contextual Overview .................................................................................................................. 7 3.0 Places of Potential State Significance .................................................................................... 35 3.1 Identification Methodology .......................................................................................................... 35 3.2 Verification of Places .................................................................................................................. 36 3.3 Application -

2007 Arizona Cactus Classic Program

32 Elite Teams - One Champion - You don't want to miss this. From May 18-20, 2007, the nation's most elite level travel basketball teams will compete in the 2nd Annual Arizona Cactus Classic presented by Precision Toyota & First Magnus, to be played at the University of Arizona's renowned McKale Memorial Center and Bear Down Gymnasium. TED BY Magnus PRESEN AND First Precision Toyota -20 2007 May 18 OFFICIAL PROGRAM TM Additional Support provided by: John Rowe, Tim Garrigan, George Rountree, Peter Evans, Alan Norville, Robert Hansen, Jack Handley, Nyal Leslie, Stanley Feldman, David & Susan Cohn, and Bob Bretz. 3 DAYS • 32 TEAMS • 79 GAMES • $10 BUCKS WHERE: McKale Memorial Center and Bear Down Gymnasium on the campus For ticket information and event details, visit: of The University of Arizona. www.azcactusclassic.com © Copyright 2007, Jim Storey Productions, LLC. Welcome to the Arizona Cactus Classic-2007 May 18, 2007 Dear Basketball Enthusiast: I say “Basketball Enthusiast” because if you are sponsoring, playing, scouting, or attending the 2nd Annual Arizona Cactus Classic then you really must be a basketball enthusiast. With 79 basketball games to be played in two and a half days, this event is truly for those who enjoy the wonderful game of basketball. Thank you for choosing to be a part of this unique basketball environment. I know that many of you have come to Tucson, Arizona from a long distance and I appreciate your willingness to be a part of this event. There have been many people and businesses that have helped make this event possible through their volunteerism and fi nancial support. -

Rotch JUL 13 1973

A HOUSING SYSTEM: A STUDY OF AN INDUSTRIALIZED HOUSING SYSTEM IN METAL By: BRUCE M. HAXTON Bachelor of Architecture, University of Minnesota (1969) Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE, ADVANCED STUDIES A t the MA SSACHUSETT S INST ITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May, 1973 Author.............. .. .... .. ...... ... .. ... - Department of Arch itecture Certified by. .. .. .. .. .- . ..-.. ' . .. ... b. ..... -- Thesis Advisor Accepted by.......... -- - Ch i rman, Dew&icr.mental Committee on Graduate Students Rotch JUL 13 1973 May 11, 1973 Dean William Porter School of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Dear Dean Porter: In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture, Advanced Studies, I hereby submit this thesis entitled: A HOUSING SYSTEM: A STUDY OF AN INDUSTRIALIZED HOUSING SYSTEM IN METAL. Respectfully, Bruce M. Haxton ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to gratefully acknowledge the following people, whose assistance and advice have contributed significantly to the development of this thesis. Waclaw P. Zalewski Professor of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Thesis Advisor Eduardo Catalano Professor of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Aurthor D. Bernhardt Professor of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Ezra Ehrenkrantz Visiting Professor Massachusetts Institute of Technology James Bock Executive Vice President Bock Industries Incorporated TABLE OF CONTENTS Ti tle Page Letter of Submittal Acknowledgements Table of Contents Abstract Introduct ion Design Analysis Design Constraints Methodology Design Considerations Areas for Further Study User Requirement Study Market Study Design Study Design Categories Design Components Delivery Components Unit Plans Unit Cluster Plans Details Unit Model Bibliography ABSTRACT A HOUSING- SYSTEM: A STUDY OF AN INDUSTRIALIZED HOUSING SYSTEM IN METAL By BRUCE M. -

Artistic Evolution at the Confluence of Cultures

Dochaku: Artistic Evolution at the Confluence of Cultures Toshiko Oiyama A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art, College of Fine Arts University of New South Wales 2011 Acknowledgements Had I known the extent of work required for a PhD research, I would have had a second, and probably a third, thought before starting. My appreciation goes to everyone who made it possible for me to complete the project, which amounts to almost all with whom I came in contact while undertaking the project. Specifically, I would like to thank my supervisors Dr David McNeill, Nicole Ellis, Dr Paula Dawson, Mike Esson and Dr Diane Losche, for their inspiration, challenge, and encouragement. Andrew Christofides was kind to provide me with astute critiques of my practical work, while Dr Vaughan Rees and my fellow PhD students were ever ready with moral support. Special thanks goes to Dr Janet Chan for giving me the first glimpse of the world of academic research, and for her insightful comments on my draft. Ms Hitomi Uchikura and Ms Kazuko Hj were the kind and knowledgeable guides to the contemporary art world in Japan, where I was a stranger. Margaret Blackmore and Mitsuhiro Obora came to my rescue with their friendship and technical expertise in producing this thesis. My sister Setsuko Sprague and my mother Nobuko Oiyama had faith in my ability to complete the task, which kept me afloat. Lastly, a huge thanks goes to my husband Derry Habir. I hold him partly responsible for the very existence of this project – he knew before I ever did that I wanted to do a PhD, and knew when and how to give me a supporting hand in navigating its long process. -

PENTAGON OFFICE BUILDING COMPLEX Other Name/Site Number: the Pentagon

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 THE PENTAGON Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: PENTAGON OFFICE BUILDING COMPLEX Other Name/Site Number: The Pentagon 2. LOCATION Street & Number: U.S. 1, Va. 110, and Not for publication: Interstate 395 City/Town: Arlington Vicinity:__ State: Virginia County: Arlington Code: 013 Zip Code: 20301 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private:__ Building(s): X Public-local:__ District:__ Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal: X Structure:__ Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 ____ buildings 1 sites (helipad) ____ structures ____ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 4 Name of related multiple property listing: NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 THE PENTAGON Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Iep 291858 L I E3 R A- "Johansen Village Hansenarium"

IEP 291858 L I E3 R A- "JOHANSEN VILLAGE HANSENARIUM" A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master in Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 15 August 1958. SUBMITTED BY CHARLES A. BLONDHEIM, JR. PIETRO BELLUSCHI Dean, School of Architecture and Planning LAWRENCE B. ANDERSON Head, Department of Architecture p Boston, Massachusetts 15 August 1958 Dean Pietro Belluschi School of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts Dear Sir: In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master in Architecture, I submit my Thesis entitled "Johansen Village Hansenarium". Sincerely yours, Charles A. Blondheim, Jr. DEDICATION The winter was cold the summer was hot but Maxie my wif e kept typing & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere thanks and appreciation for their critism, advise, and inspiration. Dean Pietro Belluschi Dean of the Department of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts Professor Lawrence B. Anderson Head of Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts Professor Eduardo Catalano Critic Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts Professor Horacio Caminos Guest Critic School of Design, North Carolina State College Raleigh, North Carolina Hideo Sasaki Guest Critic Department of Architecture, Harvard University Cambridge, Massachtsetts Fred Taylor Guest Critic School of Design, North Carolina State College Raleigh, North Carolina Paul M. Heffernam Head of School of Architecture Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, Georgia Dr. E* B. Johnwick Medical Officer In Charge U. S. Public Health Service Hospital Carirille, Louisiana Dr. R. R. Wolcott Clinical Director U. S. Public Health Service Hospital Carvi.le, Louisiana F.