A Review of the Gram Swaraj Project in Koppal District, Karnataka: Some Policy Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

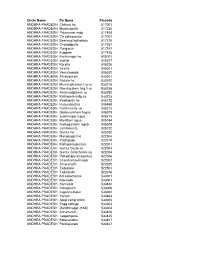

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

HŒ臬 A„簧綟糜恥sµ, Vw笑n® 22.12.2019 Š U拳 W

||Om Shri Manjunathaya Namah || Shri Kshethra Dhamasthala Rural Development Project B.C. Trust ® Head Office Dharmasthala HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ, vw¯ºN® 22.12.2019 Š®0u®± w®lµu® îµ±°ªæX¯Š®N®/ N®Zµ°‹ š®œ¯‡®±N®/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛ‡®± wµ°Š® wµ°î®±N¯r‡®± ªRq® y®‹°£µ‡®± y®ªq¯ºý® D Nµ¡®w®ºruµ. Cu®Š®ªå 50 î®±q®±Ù 50 Oʺq® œµX®±Ï AºN® y®lµu®î®Š®w®±Ý (¬šµ¶g¬w®ªå r¢›Š®±î®ºqµ N®Zµ°‹/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ y®u®ï î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 25 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ î®±q®±Ù îµ±ªæX¯Š®N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ Hš¬.Hš¬.HŒ¬.› /z.‡®±±.› ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ‡µ²ºvSµ 3 î®Ç®Áu® Nµ©š®u® Aw®±„Â®î® î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 30 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ ) î®±±ºvw® œ®ºq®u® š®ºu®ý®Áw®NµÊ B‡µ±Ê ¯l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. š®ºu®ý®Áw®u® š®Ú¡® î®±q®±Ù vw¯ºN®î®w®±Ý y®äqµã°N®î¯T Hš¬.Hº.Hš¬ î®±²©N® ¯Ÿr x°l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. œ¯cŠ¯u® HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ A†Ãw®ºu®wµS®¡®±. Written test Sl No Name Address Taluk District mark Exam Centre out off 100 11 th ward near police station 1 A Ashwini Hospete Bellary 33 Bellary kampli 2 Abbana Durugappa Nanyapura HB hally Bellary 53 Bellary 'Sri Devi Krupa ' B.S.N.L 2nd 3 Abha Shrutee stage, Near RTO, Satyamangala, Hassan Hassan 42 Hassan Hassan. -

1 : in the High Court of Karnataka Dharwad Bench

: 1 : WP No.100587/2018 IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA DHARWAD BENCH DATED THIS THE 07t h DAY OF FEBRUARY 2018 BEFORE THE HON’BLE MRS.JUSTICE K.S.MUDAGAL WRIT PETITION No.100587 of 2018 [LB-RES] BETWEEN : KALAKAPPA S/O KUNATAPPA BALUTAGI AGE: 44 YEARS, R/O: HIREMANNAPUR, TQ: KUSHTAGI, DIST: KOPPAL. ... PETITIONER (By Sri. K L PATIL ADV.) AND: 1. THE STATE OF KARNATAKA RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND PANCHAYAT RAJ, VIDHANA SOUDHA, BENGALURU-01, REPRESENTED BY ITS UNDER SECRETARY. 2. ZILLAL PANCHAYAT KOPPAL DISTRICT, KOPPAL, BY ITS CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER. 3. THE ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER KOPPAL SUB DIVISION, KOPPAL. 4. HIREMANNAPUR GRAM PANCHAYAT HIREMANNAPUR VILLAGE, TQ: KUSHTAGI, DIST: KOPPAL, BY ITS PANCHAYAT DEVELOPMENT OFFICER. 5. SMT.LAXMI W/O YAMANURAPPA VADDAR : 2 : WP No.100587/2018 AGE: MAJOR (NOT KNOWN) OCC: MEMBER GP R/O: HIREMANNAPUR, TQ: KUSHTAGI, DIST: KOPPAL. 6. DODDABASAPPA S/O CHANNABASANGOUDA POLICE PATIL, AGE: MAJOR (NOT KNOWN) OCC: MEMBER GP R/O: HIREMANNAPUR, TQ: KUSHTAGI, DIST: KOPPAL. 7. TIPPANNA S/O HANAMAPPA KURNAL AGE: MAJOR (NOT KNOWN) OCC: MEMBER GP R/O: HIREMANNAPUR, TQ: KUSHTAGI, DIST: KOPPAL. 8. SIDDANAGOUDA S/O PAMPANGOUDA PATIL AGE: MAJOR (NOT KNOWN) OCC: MEMBER GP R/O: HIREMANNAPUR, TQ: KUSHTAGI, DIST: KOPPAL. 9. CHATRAPPA S/O SHANKRAPPA BAJANTRI AGE: MAJOR (NOT KNOWN) OCC: MEMBER GP R/O: HIREMANNAPUR, TQ: KUSHTAGI, DIST: KOPPAL. 10. SMT.BHAGYALAXMI W/O ISHAPPA BUKKANATTI AGE: MAJOR (NOT KNOWN) OCC: MEMBER GP R/O: HIREMANNAPUR, TQ: KUSHTAGI, DIST: KOPPAL. 11. HANAMGOUDA S/O MELAGOUDA PATIL AGE: MAJOR (NOT KNOWN) OCC: MEMBER GP R/O: HIREMANNAPUR, TQ: KUSHTAGI, DIST: KOPPAL. -

Of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN

Page 1 of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR_SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN REG_NUM QUALIF MOBILE EMAIL 7356 1994S 2091 345 28.04.49 KRISHNAMSETY D-12, IVRI, QTRS, HEBBAL, KARNATAKA VCI/85/94 B.V.Sc./APAU/ PRABHODAS BANGALORE-580024 KARNATAKA 8992 1994S 3750 425 03.01.43 SATYA NARAYAN SAHA IVRI PO HA FARM BANGALORE- KARNATAKA VCI/92/94 B.V.Sc. & 24 KARNATAKA A.H./CU/66 6466 1994S 1188 295 DINTARAN PAL ANIMAL NUTRITION DIV NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2150/91 BVSc & 9480613205 [email protected] ADUGODI HOSUR ROAD AH/BCKVV/91 BANGALORE 560030 KARNATAKA 7200 1994S 1931 337 KAJAL SANKAR ROY SCIENTIST (SS) NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2254/93 BVSc&AH/BCKVV/93 9448974024 [email protected] ADNGODI BANGLORE 560030 m KARNATAKA 12229 1995 2593 488 26.08.39 KRISHNAMURTHY.R,S/ #1645, 19TH CROSS 7TH KARNATAKA APSVC/205/94,VCI/61 BVSC/UNI OF 080 25721645 krishnamurthy.rayakot O VEERASWAMY SECTOR, 3RD MAIN HSR 7/95 MADRAS/62 09480258795 [email protected] NAIDU LAYOUT, BANGALORE-560 102. 14837 1995 5242 626 SADASHIV M. MUDLAJE FARMS BALNAD KARNATAKA KAESVC/805/ BVSC/UAS VILLAGE UJRRHADE PUTTUR BANGALORE/69 DA KA KARANATAKA 11694 1995 2049 460 29/04/69 JAMBAGI ADIGANGA EXTENSION AREA KARNATAKA 591220 KARNATAKA/2417/ BVSC&AH 9448187670 shekharjambagi@gmai RAJASHEKHAR A/P. HARUGERI BELGAUM l.com BALAKRISHNA 591220 KARANATAKA 10289 1995 624 386 BASAVARAJA REDDY HUKKERI, BELGAUM DISTT. KARNATAKA KARSUL/437/ B.V.SC./GAS 9241059098 A.I. KARANATAKA BANGALORE/73 14212 1995 4605 592 25/07/68 RAJASHEKAR D PATIL, AMALZARI PO, BILIGI TQ, KARNATAKA KARSV/2824/ B.V.SC/UAS S/O DONKANAGOUDA BIJAPUR DT. -

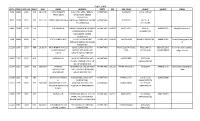

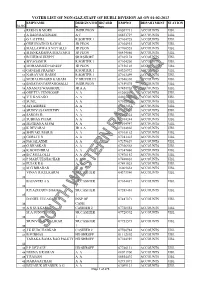

Hubli Voter List-2013

VOTER LIST OF NON-GAZ STAFF OF HUBLI DIVISION AS ON 01-02-2013 EMPNAME DESIGNATIO IDCARD EMPNO DEPARTMENT STATION SL.NO N NO 1 REKHA B MORE JMDR PEON 00207731 ACCOUNTS UBL 2 A BABURATHNAM A C 06431719 ACCOUNTS UBL 3 G LALITHA R SORTER 1 07104728 ACCOUNTS UBL 4 GURUNATH D RAWAL JD PEON 07104935 ACCOUNTS UBL 5 MALLAWWA S NITTALLI JD PEON 07760528 ACCOUNTS UBL 6 SHANKARAPPA M.KUDAGI JD PEON 06434060 ACCOUNTS UBL 7 B I HURALIKUPPI SR RSHORT 07105174 ACCOUNTS UBL 8 SIVAGAMI R R SORTER 1 07104200 ACCOUNTS UBL 9 MOHAMMED HANEEF JD PEON 07456104 ACCOUNTS UBL 10 GANESH PRASAD R SORTER 1 00328972 ACCOUNTS UBL 11 NARAYAN BADDI R SORTER 1 07103499 ACCOUNTS UBL 12 MURALIDHARD KADAM V DRIVER III 07348370 ACCOUNTS UBL 13 BASAVANTAPPAHOSALLI JMDR PEON 07459075 ACCOUNTS UBL 14 ANAND.S.WAGMORE JR A A 07450916 ACCOUNTS UBL 15 GRETTA PUNNOOSE A A 01206564 ACCOUNTS UBL 16 V V KANAGO A A 04695240 ACCOUNTS UBL 17 SUNIL A A 07102768 ACCOUNTS UBL 18 JAYASHREE A A 07103451 ACCOUNTS UBL 19 SRINIVASAMURTHY A A 07103463 ACCOUNTS UBL 20 SAROJA B A A 07104224 ACCOUNTS UBL 21 SUBHAS PUJAR A A 07104248 ACCOUNTS UBL 22 MEGHANA M PAI A A 07104947 ACCOUNTS UBL 23 K DEVARAJ JR A A 07104960 ACCOUNTS UBL 24 SHIVAKUMAR.B A A 07105162 ACCOUNTS UBL 25 GORLI V N A A 07241422 ACCOUNTS UBL 26 NAGALAXMI A A 07279619 ACCOUNTS UBL 27 G.BHASKAR A A 07306568 ACCOUNTS UBL 28 K.GOVINDRAJ A A 07347080 ACCOUNTS UBL 29 B.C.MULLOLLI A A 07476152 ACCOUNTS UBL 30 P MARUTESHACHAR A A 07488816 ACCOUNTS UBL 31 PUJAR R S A A 07491025 ACCOUNTS UBL 32 M G BIRADAR A A 16069638 ACCOUNTS UBL VINAY R -

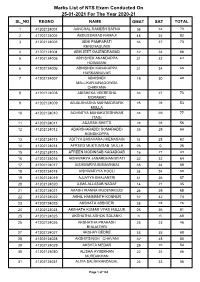

Marks List of NTS Exam Conducted on 25-01-2021 for the Year 2020-21 SL NO REGNO NAME GMAT SAT TOTAL

Marks List of NTS Exam Conducted On 25-01-2021 For The Year 2020-21 SL_NO REGNO NAME GMAT SAT TOTAL 1 41202124001 AANCHAL RAMESH BAFNA 36 34 70 2 41202124002 ABDUSSAMAD NAMAJI 48 34 82 3 41202124003 ABHI PAMPAPATI 36 37 73 KENCHAGUNDI 4 41202124004 ABHIJEET GAJENDRAGAD 32 34 66 5 41202124005 ABHISHEK ANANDAPPA 31 32 63 HOSAMANI 6 41202124006 ABHISHEK KANAKAPPA 31 34 65 HURKANNAVAR 7 41202124007 ABHISHEK 19 30 49 MALLIKARJUNAGOWDA CHIKKANA 8 41202124008 ABISHEKA VEERESHA 33 37 70 MORABAD 9 41202124009 ABJALBHASHA MAHMADRAFIK 25 28 53 MULLA 10 41202124010 ACHINTYA MAHAKUTESHWAR 38 39 77 ITAGI 11 41202124011 ADARSH SHETTI 28 28 56 12 41202124012 ADARSHARADDI SOMARADDI 35 29 64 KONDIKOPPA 13 41202124013 ADITYA BASAVARAJ MENASAGI 34 28 62 14 41202124014 AFREED MUKTUMSAB MULLA 26 0 26 15 41202124015 AFREEN MODINSAB KAGADGAR 16 27 43 16 41202124016 AISHWARYA JANARDHAN BYATI 32 32 64 17 41202124017 AISHWARYA M MAVINKAI 35 34 69 18 41202124018 AISHWARYYA HOOLI 34 24 58 19 41202124019 AJJAYYA BHAJANTRI 31 36 67 20 41202124020 AJMA ALLASAB NADAF 14 21 35 21 41202124021 AKASH IRANNA MUDENAGUDI 26 39 65 22 41202124022 AKHIL HANMANTH KONNUR 32 42 74 23 41202124023 AKSHATA ABBIGERI 38 38 76 24 41202124024 AKSHATA KUMAR VYAS HULLUR 25 36 61 25 41202124025 AKSHATHA ASHOK SOLANKI 0 0 AB 26 41202124026 AKSHATHA PRAKASH 23 23 46 BHAJATHRI 27 41202124027 AKSHAY BEDRE 33 35 68 28 41202124028 AKSHITSINGH CHAVANI 32 48 80 29 41202124029 AKSHTA MEDAR 29 25 54 30 41202124030 ALISHA AYUBKHAN 22 24 46 MURDAKHAN 31 41202124031 ALIYA SALIM KANDAGAL 23 33 56 Page 1 -

Etiology and Symptomatology, Survey and Host Range Studies of Yellow Mosaic Disease on Horsegram Transmitted by Whitefly (B

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2020) 9(2): 766-786 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 9 Number 2 (2020) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2020.902.094 Etiology and Symptomatology, Survey and Host Range Studies of Yellow Mosaic Disease on Horsegram Transmitted by Whitefly (B. tabaci) in North Eastern Karnataka, India H. S. Ganesh1*, M. R. Govindappa2, D. S. Ashwathanarayana1 and L. N. Yogesh3 1Department of Plant Pathology, College of Agriculture, UAS, Raichur, Karnataka, India, 584104 2Department of Plant Pathology, KVK, and ARS Hagari, UAS, Raichur, Karnataka, India, 584104 3Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding, ARS, Hagari, UAS, Raichur, Karnataka, India, 584104 *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Yellow mosaic disease (YMD) on horsegram caused by begomovirus belongs to family geminiviridae is an emerging threat for crop cultivation in peninsular India and in many parts of Karnataka. The present etiological studies indicated that the K e yw or ds symptoms characterized by faint yellow discoloration on the young leaves in the beginning as disease progresses, the leaves show characteristic symptoms of Horsegram, Yellow mottling. The mottling are irregular, small, greenish yellow in colour and mosaic disease, intermixed with normal green patches, later on the mottling become enlarged and Geminivirus, turn bright yellow and eventually become completely bleached. The average Whitefly, Incidence incidence of horsegram yellow mosaic disease (HgYMD) varied from 10.68 to Article Info 44.91% in major surveyed areas of north eastern Karnataka. The maximum Accepted: incidence (44.91%) was recorded in Kushtagi taluk of Karnataka. -

Police Station List

PS CODE POLOCE STATION NAME ADDRESS DIST CODEDIST NAME TK CODETALUKA NAME 1 YESHWANTHPUR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 2 JALAHALLI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 3 RMC YARD PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 4 PEENYA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 5 GANGAMMAGUDI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 6 SOLADEVANAHALLI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 7 MALLESWARAM PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 8 SRIRAMPURAM PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 9 RAJAJINAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 10 MAHALAXMILAYOUT PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 11 SUBRAMANYANAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 12 RAJAGOPALNAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 13 NANDINI LAYOUT PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 14 J C NAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 15 HEBBAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 16 R T NAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 17 YELAHANKA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 18 VIDYARANYAPURA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 19 SANJAYNAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 20 YELAHANKA NEWTOWN PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 21 CENTRAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 22 CHAMARAJPET PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 23 VICTORIA HOSPITAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 24 SHANKARPURA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 25 RPF MANDYA MANDYA 22 MANDYA 5 Mandya 26 HANUMANTHANAGAR PS BANGALORE -

Koppal District

GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY) DISTRICT IRRIGATION PLAN KOPPAL DISTRICT 2016 CONTENTS Chapter Page Contents No No PMKSY - Introduction 1-7 I General Information of the district 8-30 II District water profile 31-34 III Water availability 35-44 IV Water requirement/ demand 45-62 V Strategic action plan for irrigation 63-101 Conclusions 102-103 Appendices 104-167 i LIST OF TABLES Table No Title of Tables Page No 1.1 District profile 10 1.2 Taluk wise population 11 1.3 Details of house holds 12 1.4 Large animal population 14 1.5 Small animal population 15 1.6 Rainfall pattern in Koppal district 17 1.7 Soil types of Koppal district 19 1.8 Slope characteristic 20 1.9 Soil erosion and runoff status 27 1.10 Land use pattern in Koppal district 29 2.1 Crop wise- season-wise irrigated area in Koppal 31 district 2.2 Area, Production and Productivity of major 33 agricultural crops 2.3 Status of irrigated area in Koppal district 34 3.1 Status of water availability 36 3.2 Status of ground water in Koppal district 38 3.3 Status of command area 41 3.4 Status of ongoing lift irrigation schemes 41 3.5 Source wise irrigated area 42 3.6 Water availability in Koppal district 43 4.1 Domestic water requirement /Demand of Koppal 48 district & projected for 2020 4.2 Water requirement of horticultural/ agril crops 52 4.3 Water requirement of livestock in Koppal district in 54 2012 and projected for 2020 4.4 Water demand for industries in Koppal district 56 4.5 Water demand for power generation in -

NCVT Private/Unaided ITI List

Annexure-3A Karnataka State Private Un-Aided ITIs (Pvt ITIs) Details Sl. MIS Code of Rural / Division ITI Name & Address District No. ITI Urban Aravinda Pvt ITI, Sanjaynagar, Doddballapur, 1 PR29001232 Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural District Divya Jyothi Pvt ITI, Vishwa Building, Chikkanna 2 PR29000490 Bengaluru Layout, Nelamangala Town, Bengaluru Rural Rural Bengaluru Rural District GS Pvt ITI, CGSS Campus, College Road, Hosakote 3 PR29000641 Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural Town, Bengaluru Rural District GS Pvt ITI, Pillagumpe, Industrial Area, Hosakote 4 PR29000640 Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural Taluk, Bangalore Road, Bengaluru Rural District JRS Pvt ITI Nelamangala, Kuluvanahalli, 5 PR29000753 Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural Nelamangala Taluk, Bengaluru Rural District M V M Pvt ITI, Old Madrass Road, Hosakote 6 PR29000273 Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural Town, Hosakote, Bengaluru Rural District Pragathi Pvt ITI, Fort Street, Vijaypura, Bengaluru 7 PR29000023 Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural Rural District R.L. Jalappa Pvt ITI, Kodigehalli, Doddaballapura, 8 PR29000409 Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural District Rajalakshmi Pvt ITI, 174, Next to GEF Eye 9 PR29000443 Bengaluru Hospital, Akashavani Extension, Hosakote Town, Rural Bengaluru Rural Hosakote, Bengaluru Rural District Shankari Pvt ITI, Koratagere Road, Dabaspete, 10 PR29000557 Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural Nelamangala Taluk, Bengaluru Rural District Shri Siddeswara Pvt ITI, Thyamagondlu 11 PR29000533 Bengaluru Rural Bengaluru Rural Nelamangala, -

Small Premium, Big Profit

Small Premium, Big Profit SOURCE: E-BOOK ON SUCCESS STORIES RELEASED BY THE PRIME MINISTER ON CIVIL SERVICES DAY 2017 Ramana Gouda is a one of a kind man. This 58-year-old farmer from Hiremannapur village in Kustagi Taluka in Koppal district, one of the most backward regions in Karnataka, was a high school dropout. He became a full-time farmer at a young age but that certainly didn’t mean that he was averse to learning and gaining knowledge. His motto in life was: “Look to the skies, and the stars will guide you, look to your heart and you will always know the way.” When the entire district was reeling under severe drought conditions, he came across a coloured schematic booklet of PMFBY, realised its potential and worked day and night to popularize it among fellow farmers, despondent with crop failures year on year. After the introduction of PMFBY, the District Administration worked out a way to regain the lost faith in the insurance scheme. Farm facilitators, who were farmers themselves like Ramana Gouda were assigned the task of creating awareness and confidence among the farmers and encourage them to enroll in the Scheme. ‘Small Premium – Big Profit’ (Sanna Kanthu- Dodda Labha in Kannada) was the slogan that propelled the farm facilitators into action. Ramanagouda would personally go around and meet small and marginal farmers, SC/ STs who were cut off from mainstream medium and also big farmers. He would sit with them and help them to fill up application forms in tea shops and village chavadi. -

Sub Centre List As Per HMIS SR

Sub Centre list as per HMIS SR. DISTRICT NAME SUB DISTRICT FACILITY NAME NO. 1 Bagalkote Badami ADAGAL 2 Bagalkote Badami AGASANAKOPPA 3 Bagalkote Badami ANAVALA 4 Bagalkote Badami BELUR 5 Bagalkote Badami CHOLACHAGUDDA 6 Bagalkote Badami GOVANAKOPPA 7 Bagalkote Badami HALADURA 8 Bagalkote Badami HALAKURKI 9 Bagalkote Badami HALIGERI 10 Bagalkote Badami HANAPUR SP 11 Bagalkote Badami HANGARAGI 12 Bagalkote Badami HANSANUR 13 Bagalkote Badami HEBBALLI 14 Bagalkote Badami HOOLAGERI 15 Bagalkote Badami HOSAKOTI 16 Bagalkote Badami HOSUR 17 Bagalkote Badami JALAGERI 18 Bagalkote Badami JALIHALA 19 Bagalkote Badami KAGALGOMBA 20 Bagalkote Badami KAKNUR 21 Bagalkote Badami KARADIGUDDA 22 Bagalkote Badami KATAGERI 23 Bagalkote Badami KATARAKI 24 Bagalkote Badami KELAVADI 25 Bagalkote Badami KERUR-A 26 Bagalkote Badami KERUR-B 27 Bagalkote Badami KOTIKAL 28 Bagalkote Badami KULAGERICROSS 29 Bagalkote Badami KUTAKANAKERI 30 Bagalkote Badami LAYADAGUNDI 31 Bagalkote Badami MAMATGERI 32 Bagalkote Badami MUSTIGERI 33 Bagalkote Badami MUTTALAGERI 34 Bagalkote Badami NANDIKESHWAR 35 Bagalkote Badami NARASAPURA 36 Bagalkote Badami NILAGUND 37 Bagalkote Badami NIRALAKERI 38 Bagalkote Badami PATTADKALL - A 39 Bagalkote Badami PATTADKALL - B 40 Bagalkote Badami SHIRABADAGI 41 Bagalkote Badami SULLA 42 Bagalkote Badami TOGUNSHI 43 Bagalkote Badami YANDIGERI 44 Bagalkote Badami YANKANCHI 45 Bagalkote Badami YARGOPPA SB 46 Bagalkote Bagalkot BENAKATTI 47 Bagalkote Bagalkot BENNUR Sub Centre list as per HMIS SR. DISTRICT NAME SUB DISTRICT FACILITY NAME NO.