Architecture, Materials and Languages. from Marble to Stone and Viceversa (Sicily 15Th-16Th Centuries)*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architectural Perspectives in the Cathedral of Palermo: Image-Based Modeling for Cultural Heritage Understanding and Enhancement

Inzerillo, L. and Santagati, C. (2015).Xjenza Online, 3:69{75. Xjenza Online - Journal of The Malta Chamber of Scientists www.xjenza.org DOI: 10.7423/XJENZA.2015.1.10 Research Article Architectural Perspectives in the Cathedral of Palermo: Image-Based Modeling for Cultural Heritage Understanding and Enhancement L. Inzerillo1;3, C. Santagati2;3 1University of Palermo, Department of Architecture, viale delle Scienze, Edificio 8, 90128, Palermo 2University of Catania, Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture, viale Andrea Doria n. 6, 95125, Catania 3Euro Mediterranean Institute of Science and Technology (IEMEST), Via Emerico Amari, 123 - 90139 Palermo Abstract. Palermo offers a repertoire of both artistic matic space is transformed into an aberrated pyramidal and architectural solid perspective of great beauty and prism where narratives are represented, subjects charac- in large quantity. This paper addresses the problem of terizing the context (D'Alessandro, Inzerillo & Pizzurro, the 3D survey of these works and their related study 1983; D'Alessandro & Pizzurro, 1989; Inzerillo, 2004, through the use of image-based modelling (IBM) tech- 2012). niques. We propose, as case studies, the use of IBM techniques inside the Cathedral of Palermo. Indeed, the church houses a huge and rich sculptural repertoire, dat- ing back to 16th century, which constitutes a valid field of IBM techniques application. The aim of this study is to demonstrate the effective- ness and potentiality of these techniques for geometric analysis of sculptured works. Indeed, usually the survey of these artworks is very difficult due the geometric com- plexity, typical of sculptured elements. In this study, we analysed cylindrical and planar geometries as well as carrying out an application of perspective return. -

Vladimir-Peter-Goss-The-Beginnings

Vladimir Peter Goss THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Published by Ibis grafika d.o.o. IV. Ravnice 25 Zagreb, Croatia Editor Krešimir Krnic This electronic edition is published in October 2020. This is PDF rendering of epub edition of the same book. ISBN 978-953-7997-97-7 VLADIMIR PETER GOSS THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Zagreb 2020 Contents Author’s Preface ........................................................................................V What is “Croatia”? Space, spirit, nature, culture ....................................1 Rome in Illyricum – the first historical “Pre-Croatian” landscape ...11 Creativity in Croatian Space ..................................................................35 Branimir’s Croatia ...................................................................................75 Zvonimir’s Croatia .................................................................................137 Interlude of the 12th c. and the Croatia of Herceg Koloman ............165 Et in Arcadia Ego ...................................................................................231 The catastrophe of Turkish conquest ..................................................263 Croatia Rediviva ....................................................................................269 Forest City ..............................................................................................277 Literature ................................................................................................303 List of Illustrations ................................................................................324 -

Gian Cristoforo Romano in Rome: with Some Thoughts on the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus and the Tomb of Julius II

Gian Cristoforo Romano in Rome: With some thoughts on the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus and the Tomb of Julius II Sally Hickson University of Guelph En 1505, Michel-Ange est appelé à Rome pour travailler sur le tombeau monumental du pape Jules II. Six mois plus tard, alors que Michel-Ange se trouvait à Carrare, le sculpteur et antiquaire Gian Cristoforo Romano était également appelé à Rome par Jules II. En juin 1506, un agent de la cour de Mantoue rapportait que les « premiers sculpteurs de Rome », Michel-Ange et Gian Cristoforo Romano, avaient été appelés ensemble à Rome afin d’inspecter et d’authentifier le Laocoön, récemment découvert. Que faisait Gian Cristoforo à Rome, et que faisait-il avec Michel-Ange? Pourquoi a-t-il été appelé spécifi- quement pour authentifier une statue de Rhodes. Cet essai propose l’hypothèse que Gian Cristoforo a été appelé à Rome par le pape probablement pour contribuer aux plans de son tombeau, étant donné qu’il avait travaillé sur des tombeaux monumentaux à Pavie et Crémone, avait voyagé dans le Levant et vu les ruines du Mausolée d’Halicarnasse, et qu’il était un sculpteur et un expert en antiquités reconnu. De plus, cette hypothèse renforce l’appartenance du développement du tombeau de Jules II dans le contexte anti- quaire de la Rome papale de ce temps, et montre, comme Cammy Brothers l’a avancé dans son étude des dessins architecturaux de Michel-Ange (2008), que les idées de ce dernier étaient influencées par la tradition et par ses contacts avec ses collègues artistes. -

Sicily: a Cultural Journey 11 DAYS September 2–12, 2019

Join Friendship Force on Sicily: A Cultural Journey 11 DAYS September 2–12, 2019 Speak to a travel expert today 1-800-438-7672 © 2018 EF Education First Sicily: A Cultural Journey 11 DAYS The Sicilian sun shines light on a different side YOUR TOUR PACKAGE INCLUDES of Italy. 9 nights in handpicked hotels 9 breakfasts In the midst of the Mediterranean, discover an island with personality all its own—full 6 dinners with beer or wine of flavor and teeming with one-of-a-kind art and architecture. From multicultural 1 cooking class Guided sightseeing tours Palermo to breathtaking Taormina, each and every stop on this tour of Sicily reveals Expert Tour Director & local guides unexpected treasures. Private deluxe motor coach INCLUDED HIGHLIGHTS Palermo Cathedral, home-hosted dinner in Palermo, Agrigento's Greek ruins, Piazza Amerina, Syracuse Cathedral, Sicilian cooking class, views of Mount Etna, Taormina's Greek theater TOUR PACE On this guided tour, you'll walk for about 1.5 hours daily across uneven terrain, including cobblestone streets and unpaved roads, at high altitudes. Speak to a travel expert today 1-800-438-7672 © 2018 EF Education First Itinerary Overnight flight | 1 NIGHT Taormina Region | 2 NIGHTS Day 1: Travel day Day 9: Transfer to Taormina & sightseeing tour Board your overnight flight to Palermo today. Included meals: breakfast Transfer to Taormina, where a local guide introduces you to this scenic town perched high above the sea. Palermo | 3 NIGHTS • Enjoy views of Mount Etna, Taormina Cathedral, and the Palazzo Corvaia, seat of the first Sicilian parliament Day 2: Arrival in Palermo • Visit the town’s 2nd-century Greek theater Included meals: welcome dinner Welcome to Italy! Gather with your fellow travelers at tonight’s welcome dinner. -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-25551-6 - The Latin Church in Norman Italy G. A. Loud Excerpt More information Introduction The kingdom of Sicily was created by the coronation of its first ruler, the former Count Roger II of Sicily, in Palermo cathedral on Christmas Day 1130. The kingdom that was born then lasted, despite many vicissitudes, and even some lengthy periods of division, until the creation of modern Italy in 1860. The papal bull that sanctioned the creation of this new kingdom recorded that this was proper since God had granted Roger ‘greater wisdom and power’ than other princes, and in recognition of the 1 loyal service to the papacy of his parents and himself. The pope, Anacletus II, was obviously seeking justification for his action, and the reasons for such a grant were in fact considerably more complex, and will be discussed in a later part of this book (below, chapter 3). Yet as Roger’s own con- temporary biographer noted, without mentioning the papal role in the conferment of the new royal title at all, it was appropriate that one who ‘ruled so many provinces, Sicily, Calabria and Apulia and other regions stretching almost to Rome, ...ought to be distinguished by the honour of kingship’. After raising a spurious and unhistorical, if attractive, theory that Sicily had once, in ancient times, been a kingdom, he concluded: now it was right and proper that the crown should be placed on Roger’s head and that this kingdom should not only be restored but should be spread wide to 2 include those other regions where he was now recognised as ruler. -

Ernst Kitzinger Research Papers and Photographs, 1940S–1980S

PRELIMINARY FINDING AID to the ERNST KITZINGER RESEARCH PAPERS AND PHOTOGRAPHS, 1940s-1980s Repository: Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C. Location: ICFA Stacks Identifier: MS.BZ.016 Collection Title: Ernst Kitzinger Research Papers and Photographs, 1940s-1980s Name of Creator(s): Ernst Kitzinger Inclusive Dates: 1940s-1980s Language(s): English, Italian, German Quantity: TBD SCOPE AND CONTENT Ernest Kitzinger conducted study of the twelfth-century mosaics of Norman Sicily. Dumbarton Oaks Fieldwork sponsored this project. The materials document in detail mosaics and other architectural aspects from several buildings in Sicily. The collection contains photographic negatives and oversize drawings from Capella Palatina, Cefalù, Martorana, Monreale, and other sites. HISTORICAL NOTE Ernst Kitzinger was born on December 27, 1912 in Munich and died on January 22, 2003 in Poughkeepsie, NY. He received his PhD, summa cum laude, from the University of Munich in 1934 under the direction of Wilhelm Pinder. He completed his dissertation entitled Roman Painting from the early seventh to mid-eight century1 where he discussed the influence of Byzantine art on the early stages of medieval Roman artistic production. In the same year, Kitzinger moved to England, where he worked at the Department of British and Mediaeval Antiques at the British Musum, and in 1937, he published Early Medieval Art at the British Museum.2 He eventually migrated to the United States in 1941, and “he had been created Director of Studies [at Dumbarton Oaks], a post that he held with great distinction from 1955 until 19663. From 1950 to 1951, Kitzinger was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship during his tenure as an Assistant Professor of Byzantine Art and Archaeology at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection (Dumbarton Oaks). -

Giorgio Vasari a Palazzo Abatellis: Percorsi Del Rinascimento in Sicilia / a Cura Di Stefano Piazza

11 a cura di frammenti di storia e architettura Stefano Piazza a cura di Stefano Piazza La mostra si inserisce nell’ambito delle celebrazioni per i 500 anni dalla nascita di Giorgio Vasari (1511-2011), ricorrenza che, nel corso dell’anno, è stata oggetto di numerosi eventi culturali italiani e internazionali. L’iniziativa nasce dalla collaborazione tra la Biblioteca centrale della Regione siciliana “A. Bombace”, la sezione “Sfera” del Dipartimento di Architettura dell’Università di Palermo, e la Galleria Interdisciplinare Regionale della Sicilia, istituzione che custodisce, nella prestigiosa sede di Palazzo Abatellis, due grandi dipinti su tavola di Vasari, costituenti le ricurve parti laterali del trittico della “Caduta della manna”, realizzato nel 1545 per il refettorio di Santa Maria di Monteoliveto a Napoli. Le lunette vasariane, esposte in modo permanente dal 2009 ma ancora quasi del tutto scono- sciute a studiosi e pubblico, per l’occasione sono state ricollocate secondo gli originari rap- porti dimensionali con il perduto quadro centrale e poste in relazione con il disegno pre- paratorio dello stesso Vasari, oggi custodito presso l’École nationale supérieure des beaux- arts di Parigi. Il percorso analitico, che si è avvalso anche del prezioso contributo di Claudia GIORGIO VASARI Conforti, tra le più autorevoli studiose dell’artista aretino, e delle competenze tecniche dell’Associazione Culturale LapiS, è stato svolto secondo tre tematiche connesse alla polie- drica attività vasariana e al suo contesto culturale: la pittura e l’arte -

Useful Information Before Booking Civado

FULLY ESCORTED TOURS OF ITALY We feature a wide variety of tours starting with four days to explore the best of Italy including Sicily with a perfect balance of quality and price. Our tours oer guaranteed departure dates with overnight stay in selected hotels, professional local guides, fully escorted tour, entrance fees and typical meals. Tours are guaranteed in English, Spanish and Portuguese languages. USEFUL INFORMATION BEFORE BOOKING CIVADO TOURS The Tour includes: • Transportation by deluxe motorcoach • Monolingual tour-escort in English • Accommodation in 4 stars or 3 stars hotels • Meals as per itinerary • Entrance to the archaeological site in Pompeii with “skip the line” (when included in the itinerary) • Entrance ticket to Vatican Museums & St. Peter’s Basilica with “skip the line” (when included in the itinerary) • Visits with local expert guide as per itinerary (Rome, Florence, Venice, Sorrento, Capri, Palermo, Agrigento, Siracusa) • Entrance to the archaeological sites in Sicily on our Sicilia Bella, La magia del Sud and Grand Tour d’Italia. • Entrance to the St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice with “skip the line” (when included in the itinerary) • Visit of the Blue Grotto in Capri (when included in the itinerary) Tour does not include: • Porterage service • Drinks • Entrance fees to monuments or museums when not mentioned • City tax for overnight stays (according to each city council rules) • Everything that is not mentioned in the paragraph “the tour includes” DUE TO TECHNICAL AND / OR LOGISTIC ISSUES, ITINERARIES COULD BE AMENDED We inform all Clients that rates do not include city tax when applicable. City tax will have to be paid directly from clients at the Hotel upon arrival or at the check out. -

Art and Politics at the Neapolitan Court of Ferrante I, 1458-1494

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: KING OF THE RENAISSANCE: ART AND POLITICS AT THE NEAPOLITAN COURT OF FERRANTE I, 1458-1494 Nicole Riesenberger, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Professor Meredith J. Gill, Department of Art History and Archaeology In the second half of the fifteenth century, King Ferrante I of Naples (r. 1458-1494) dominated the political and cultural life of the Mediterranean world. His court was home to artists, writers, musicians, and ambassadors from England to Egypt and everywhere in between. Yet, despite its historical importance, Ferrante’s court has been neglected in the scholarship. This dissertation provides a long-overdue analysis of Ferrante’s artistic patronage and attempts to explicate the king’s specific role in the process of art production at the Neapolitan court, as well as the experiences of artists employed therein. By situating Ferrante and the material culture of his court within the broader discourse of Early Modern art history for the first time, my project broadens our understanding of the function of art in Early Modern Europe. I demonstrate that, contrary to traditional assumptions, King Ferrante was a sophisticated patron of the visual arts whose political circumstances and shifting alliances were the most influential factors contributing to his artistic patronage. Unlike his father, Alfonso the Magnanimous, whose court was dominated by artists and courtiers from Spain, France, and elsewhere, Ferrante differentiated himself as a truly Neapolitan king. Yet Ferrante’s court was by no means provincial. His residence, the Castel Nuovo in Naples, became the physical embodiment of his commercial and political network, revealing the accretion of local and foreign visual vocabularies that characterizes Neapolitan visual culture. -

Sicily UMAYYAD ROUTE

SICILY UMAYYAD ROUTE Umayyad Route SICILY UMAYYAD ROUTE SICILY UMAYYAD ROUTE Umayyad Route Index Sicily. Umayyad Route 1st Edition, 2016 Edition Introduction Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí Texts Maria Concetta Cimo’. Circuito Castelli e Borghi Medioevali in collaboration with local authorities. Graphic Design, layout and maps Umayyad Project (ENPI) 5 José Manuel Vargas Diosayuda. Diseño Editorial Free distribution Sicily 7 Legal Deposit Number: Gr-1518-2016 Umayyad Route 18 ISBN: 978-84-96395-87-9 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, nor transmitted or recorded by any information retrieval system in any form or by any means, either mechanical, photochemical, electronic, photocopying or otherwise without written permission of the editors. Itinerary 24 © of the edition: Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí © of texts: their authors © of pictures: their authors Palermo 26 The Umayyad Route is a project funded by the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI) and led by the Cefalù 48 Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí. It gathers a network of partners in seven countries in the Mediterranean region: Spain, Portugal, Italy, Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan. Calatafimi 66 This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union under the ENPI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the beneficiary (Fundación Pública Castellammare del Golfo 84 Andaluza El legado andalusí) and their Sicilian partner (Associazione Circuito Castelli e Borghi Medioevali) and can under no Erice 100 circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or of the Programme’s management structures. -

Palermo, Cagliari, Palma De Mallorca, Valencia, Marseille, Itineraries: Genoa Departure Date: 07/04/2019

Cruise : MEDITERRANEAN Italy, Spain, France Cruise Ship: MSC DIVINA Departing from: Civitavecchia, Italy Palermo, Cagliari, Palma de Mallorca, Valencia, Marseille, Itineraries: Genoa Departure Date: 07/04/2019 Duration: 8 Days, 7 Nights Palermo Mon 8 April 2019 CULTURE AND HISTORY PALERMO AND MONREALE - PMO02 Duration 4 h A coach tour will take you past the key sights, although we will stop for a full visit of the Cathedral, built in an unusual marriage of Norman and Arab architectural styles and which houses the tombs of different Norman kings and Emperor Frederick II. Another religious site of note is the Casa Professa, one of the most important baroque churches in Palermo. You will also visit the new Mercato di San Lorenzo rich in typical Sicilian products where you can enjoy some free time for shopping. Discover the area around Palermo on a bus tour to Monreale, just 8 km away; enjoy a walking tour around the town and visit the Cathedral, home to an exquisite display of golden mosaics depicting scenes from the Old and New Testament. Free time to shop in Monreale before returning to the ship. Please note: you have to walk up some steps to visit the Cathedral in Monreale. The guide will give explanation only outside the sites; guests will visit them individually. Conservative attire recommended for visiting sites of religious importance. This tour is not suitable for guests with walking difficulties or using a wheelchair. At the end of the tour, guests must return audioguide to the guide in perfect conditions. Any damaging or loss of the audioguides may result in debiting the cost of the device to the guest. -

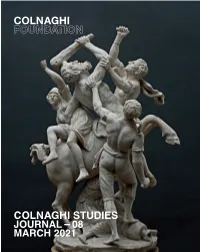

Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

JOURNAL 08 MARCH 2021 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Stijn Alsteens International Head of Old Master Drawings, Patrick Lenaghan Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Hispanic Society of America, Christie’s. New York. Jaynie Anderson Professor Emeritus in Art History, The Patrice Marandel Former Chief Curator/Department Head of European Painting and JOURNAL 08 University of Melbourne. Sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Jennifer Montagu Art Historian specializing in Italian Baroque. Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Scott Nethersole Senior Lecturer in Italian Renaissance Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Andrea Bacchi Director, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna. Larry Nichols William Hutton Senior Curator, European and American Painting and Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is to publish texts on significant Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Sculpture before 1900, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition that have recently come to light or about which new research is Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Honorary Associate in Art History, Tom Nickson Senior Lecturer in Medieval Art and Architecture, Courtauld Institute of Art, underway, as well as on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the broader context The Open University. London. of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. Francesca Baldassari Professor, Università degli Studi di Padova. Gianni Papi Art Historian specializing in Caravaggio. Bonaventura Bassegoda Catedràtic, Universitat Autònoma de Edward Payne Assistant Professor in Art History, Aarhus University. Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Editorial Committee, composed of Barcelona.