Planning & Environment Court of Queensland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O U Thern Great Barrier Reef

A1 S O Gladstone U Lady Musgrave Island T Tannum Sands Calliope H Benaraby Bustard Head E R Castle Tower NP Turkey Beach N Lady Elliot Island 69 G Lake Awoonga Town of 1770 R Eurimbula NP E G Agnes Water l A ad s t T o n e Miriam Vale B M A o Deepwater NP n R t o A1 R R d I ER R Many Peaks Baffle Creek Rules Beach E Lowmead E Burnett Hwy P a F Lake Cania c Rosedale i c C Warro NP Kalpowar o Miara a Littabella NP 1. Moore Park Beach s t Yandaran 1 69 ( 2 B Avondale 2. Burnett Heads r u 3 A3 Mungungo 3. Mon Repos c e Lake Monduran 4 H 5 4. Bargara Monto w y) 6 5. Innes Park A1 Bundaberg 7 6. Coral Cove Mulgildie 7. Elliott Heads Gin Gin Langley Flat 8. Woodgate Beach Cania Gorge NP Boolboonda Tunnel Burrum Coast NP 8 Cordalba Walkers Point Mount Perry Apple Tree Creek Burrum Heads Fraser Lake Wuruma Goodnight Scrub NP Childers Island Ceratodus Bania NP 52 Paradise Dam Hervey Bay Howard Torbanlea Eidsvold Isis Hwy Dallarnil Biggenden Binjour Maryborough Mundubbera 52 Gayndah Coalstoun Lakes Ban Ban Springs A1 Brisbane A3 Auburn River NP Mount Walsh NP LADY MUSGRAVESOUTHERN GREAT BARRIER EXPERIENCE REEF DAY TOURS Amazing Day Tours Available! Experience the Southern Great Barrier Reef in style and enjoy a scenic and comfortable transfer from Bundaberg Port Marina to Lady Musgrave Island aboard Departing from BUNDABERG Port Marina, the luxury high speed catamaran, Lady Musgrave Experience offers a premium MAIN EVENT. -

Bundaberg Region

BUNDABERG REGION Destination Tourism Plan 2019 - 2022 To be the destination of choice for the Great Barrier Reef, home of OUR VISION Australia’s premier turtle encounter as well as Queensland’s world famous food and drink experiences. Achieve an increase of Increase Overnight Increase visitation to 5% in average occupancy KEY ECONOMIC Visitor Expenditure to our commercial visitor rates for commercial $440 million by 2022 experiences by 8% GOALS accommodation FOUNDATIONAL PILLARS GREEN AND REEF OWN THE TASTE MEANINGFUL CUSTODIANS BUNDABERG BRAND As the southernmost gateway to the Sustainability is at the forefront of By sharing the vibrant stories of our Great Barrier Reef, the Bundaberg the visitor experience, with a strong people, place and produce, we will region is committed to delivering community sense of responsibility for enhance the Bundaberg region’s an outstanding reef experience the land, for the turtle population and reputation as a quality agri-tourism that is interactive, educational for the Great Barrier Reef. destination. and sustainable. ENABLERS OF SUCCESS Data Driven Culture United Team Bundaberg Resourcing to Deliver STRATEGIC PRIORITY AREAS Product and Experience Visitor Experience Identity and Influence Upskilling and Training Marketing & Events Development BT | Destination Tourism Plan (2019 - 2022) | Page 2 Bundaberg Region Today .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Visitation Summary ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Bundaberg Regional Council Multi Modal Pathway Strategy Connecting Our Region

Bundaberg Regional Council Multi Modal Pathway Strategy Connecting our Region February 2012 Contents 1. Study Background 1 2. Study Objectives 2 3. Purpose of a Multi Modal Pathway Network 3 3.1 How do we define ‘multi modal’ 3 3.2 Community Benefits of a Multi Modal Network 3 3.3 What Characteristics Should a Multi Modal Network Reflect? 4 3.4 Generators of Trips 5 3.5 Criteria for Ascertaining Location of Proposed Paths 6 4. Review of Previous Multi Modal Pathway Strategy Plans 8 4.1 Bundaberg City Council Interim Integrated Open Space and Multi Modal Pathway Network Study 2006 8 4.2 Burnett Shire Walk and Cycle Plan – For a Mobile Community 2004 9 4.3 Bundaberg – Burnett Regional Sport and Recreation Strategy 2006 9 4.4 Kolan Shire Sport and Recreation Plan 2004 10 4.5 Bundaberg Region Social Plan 2006 10 4.6 Woodgate Recreational Trail 10 5. Proposed Multi Modal Pathway Strategy 11 5.1 Overall Outcomes of the Multi-Modal Pathway Network 11 5.2 Hierarchy Classification 11 5.3 Design and Construction Standards 13 5.4 Weighting Criteria for Locating Pathways and Prioritising Path Construction 14 5.5 Pathway Network for the Former Bundaberg City Council Local Government Area 17 5.6 Pathway Network for the former Burnett Shire Council Local Government Area 18 5.7 Pathway Network for the former Isis Shire Council Local Government Area 20 5.8 Pathway Network for the Former Kolan Shire Council Local Government Area 21 5.9 Integration with Planning Schemes 21 5.10 Other Pathway Opportunities 22 6. -

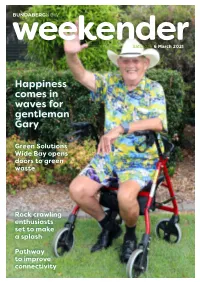

Download PDF File

weekender Saturday 6 March 2021 Happiness comes in waves for gentleman Gary Green Solutions Wide Bay opens doors to green waste Rock crawling enthusiasts set to make a splash Pathway to improve connectivity contents Green Solutions 3 Wide Bay opens doors to green waste Cover story Happiness comes 4 in waves for gentleman Gary What’s on in the Bundaberg 6 Region Magical world unleashed to 7 celebrate parks week Pathway to 8 improve connectivity Gary Ostrofski. Photo of the week Refill Not Landfill 9 sets up shop Photo by @kararosenlund at Stocklands Ladies Garage Party 10 inspired by love of motorbikes Isis Mill career 12 of 50 years honoured Gardening hobby blossoms into 14 healthier lifestyle Bargara sprint 16 triathlon turns on family friendly charm Rock crawling 17 enthusiasts set to make a splash NEWS Green Solutions Wide Bay opens doors to green waste Ashley Schipper Green Solutions Wide Bay is now taking on the region’s green waste after a soft opening at the new facility on Windermere Road this week. The state-of-the-art business is providing Bundaberg Region residents with a place to Greensill Farming Group’s Head of Planning, Infrastructure and Projects Nathan Freeman dispose of green waste for free, which will then at the site on Windermere Road. be turned into compost for utilisation across “By utilising our facility, we can all act to reduce Greensill Farming sites. our planet’s carbon footprint, combat pollution According to Damien Botha, CEO of Greensill and enrich the soil by giving green waste a new Farming, the open-window composting facility life.” is a first for the region and a project which was Damien said the new business venture had adding to the positive recycling message. -

Bundaberg Sport and Recreation Strategy Final.Indd

BBundabergundaberg RRegegiionalonal CCounounccilil regional sport and recreation strategy July 2010 BBundabergundaberg RRegionalegional CCouncilouncil regional sport and recreation strategy July 2010 This Strategy has been prepared by: ROSS Planning Pty Ltd ABN 41 892 553 822 9/182 Bay Terrace (Level 4 Flinders House) Wynnum QLD 4178 PO Box 5660 Manly QLD 4179 “The Regional Sport and Recreation Strategy was developed in partnership with the Telephone: (07) 3901 0730 Queensland Government and the Bundaberg Regional Council to get more Queens- Fax: (07) 3893 0593 landers active through sport and recreation.” © 2010 ROSS Planning Pty Ltd This document may only be used for the purposes for which it was commissioned and in accordance with the terms of engagement for the commission. Unauthorised use of this document in any form whatsoever is prohibited. Table of Contents 1. Recommendations 1 Viability of Sport and Recreation Groups 2 Open Space and Council Planning 4 Maintenance and Improvement of Existing Facilities 7 and Programs New Facilities, Programs and Initiatives 8 2 Purpose and Objectives 9 Purpose 9 Background 9 Study Approach 9 3 Background Research 11 Existing Plans and Studies 11 Demographics 13 Trends in Sport and Recreation 15 4 Demand Assessment 17 Consultation 17 Community Meetings 17 Sport and Recreation Clubs and Organisations 19 Sport and Recreation Clubs Survey 20 Schools Survey 26 5 Open Space 28 Open Space Outcomes 28 Guiding Principles 28 Open Space Classifi cations 29 Open Space Assessment 31 6 Appendices 33 Acronyms -

Referral of Proposed Action Form

Referral of proposed action What is a referral? The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (the EPBC Act) provides for the protection of the environment, especially matters of national environmental significance (NES). Under the EPBC Act, a person must not take an action that has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on any of the matters of NES without approval from the Australian Government Environment Minister or the Minister’s delegate. (Further references to ‘the Minister’ in this form include references to the Minister’s delegate.) To obtain approval from the Environment Minister, a proposed action should be referred. The purpose of a referral is to obtain a decision on whether your proposed action will need formal assessment and approval under the EPBC Act. Your referral will be the principal basis for the Minister’s decision as to whether approval is necessary and, if so, the type of assessment that will be undertaken. These decisions are made within 20 business days, provided sufficient information is provided in the referral. Who can make a referral? Referrals may be made by or on behalf of a person proposing to take an action, the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency, a state or territory government, or agency, provided that the relevant government or agency has administrative responsibilities relating to the action. When do I need to make a referral? A referral must be made for actions that are likely to have a significant impact on the following matters protected by Part 3 of the EPBC -

Childers Leaves Stamp on History Bundaberg Rum Distillery to Re-Open Award Winning Visitor Experience

weekenderSaturday 22 August 2020 Childers leaves stamp on history Bundaberg Rum Distillery to re-open award winning visitor experience Full steam ahead for Bundaberg to Gin Gin Rail Trail Creativity unleashed at Milbi Magic Snip and Sip contents Bundaberg Rum Distillery to 3 re-open award winning visitor experience Cover story Childers leaves 4 stamp on history What’s on in the Bundaberg 6 Region Bundaberg leads with disability 7 parking Vietnam Veterans Day observed 8 across region Creativity unleashed at Milbi 9 Magic Snip and Sip Building a Healthy Photo of the week Great photo by @jmcdlandscapes Bundaberg Alliance 10 launched Full steam ahead for Bundaberg to Gin 12 Gin Rail Trail Jobs team skills students in resume 14 writing World’s hottest chilli shop opens 17 in Bundaberg In our Garden: 18 Bullyard Beauty New program encourages students 21 to volunteer BUSINESS Bundaberg Rum Distillery re-opens Monday 24th August. Bundaberg Rum Distillery to re-open award winning visitor experience Megan Dean Australia’s multi award-winning ‘Best welcoming people to the Distillery, but now Distillery Experience’, the Bundaberg more so than ever. We’re thrilled to be able to Rum Distillery, is set to re-open its share our world-class rum with our guests at Bundaberg Rum’s iconic home, particularly in doors from Monday 24th August. a year that we have again been recognised at Guests will once again be able to cross the the Australian Tourism Awards as Best Distillery country’s best distillery experience off their Experience.” bucket list and visit the home of the iconic “The health and safety of our staff and guests Bundy R Bear, as the Queensland Government is of our utmost concern, so visitors can be continues to ease lockdown restrictions. -

Paradise Lane Christmas Lights a Labour of Love

weekenderSaturday 12 December 2020 Paradise Lane Christmas Lights a labour of love Pearl shines at Kobi claims spot 100th birthday in Queensland celebrations life saving team Phytocap Bundaberg technology trial to ‘most generous transform landfill town in Australia’ contents Mayor and RSL call for new 3 HMAS Bundaberg Cover story Paradise Lane Christmas Lights 4 a labour of love What’s on in the Bundaberg 6 Region Phytocap technology trial to 7 transform landfill Small school charm highlight 8 of Kaye’s career Photo of the week Teaching a Photo by @this_orchard_life passion for retiring 9 principal Pearl shines at 100th birthday 10 celebrations Family gathers for 75th wedding 11anniversary A tale of two much-loved 12 gardens Bundaberg ‘most generous 14 town in Australia’ Kobi claims spot in Queensland 16 life-saving team Warren Zunker retires after 55 years 17 of farming NEWS The second HMAS Bundaberg, which was destroyed by fire in 2014. Photo: RAN Mayor and RSL call for new HMAS Bundaberg Michael Gorey build tradition and foster a sense of esprit de The Bundaberg RSL Sub-branch corps among ship’s companies. “The first HMAS Bundaberg launched on has endorsed a call by Mayor Jack 1 December 1941 and saw active service in the Dempsey for a new HMAS Bundaberg Second World War,” he said. to be commissioned in the Royal “On 28 October 1945 she arrived at the Port Australian Navy. of Bundaberg where she was given an official reception by our grateful citizens.” Mayor Dempsey wrote last month to Defence Minister Linda Reynolds and Chief of Navy, Vice Bundaberg paid off at Brisbane on 26 March Admiral Michael Noonan. -

Bundaberg Region Visitor

MAP MAP MAP AAOK Riverdale Caravan Park REF J22 Bundy Bogan & Sherree’s Disposals REF K22 Moncrieff Entertainment Centre REF J22 Whether you have your own caravan, We sell souvenirs, picking needs, The Moncrieff Entertainment Centre @BUNDABERGRUM require a campsite or are simply outdoors, Chern’ee Sutton original art, is the cultural heart of the Bundaberg RUM BUNDABERG traveling around the country, AAOK metal detectors and hunting gear. region. Boasting over 800 seats in its (07) 4131 2999 4131 (07) Riverdale Caravan Park has your After hours appointments available for theatre, the venue is a hub of live events BUNDABERGRUM.COM.AU H21 and cinema. The Moncrieff is your go-to REF accommodation needs covered, and at groups. venue for an entertainment experience MAP competitive prices. Pet friendly sites. with a difference. SAVE AND ONLINE BOOK A: 6 Perry St, Bundaberg North A: 177 Bourbong Street, Bundaberg P: (07) 4153 6696 A: 67 Bourbong St, Bundaberg P: 07 4130 4100 E: [email protected] P: 07 4198 1784 / 0419790633 E: [email protected] W: www.riverdalecaravanpark.com.au E: [email protected] W: moncrieff-bundaberg.com.au MAP MAP MAP Bargara Brewing Co & The Brewhouse REF K23 Hinkler Central Shopping Centre REF J24 Ohana Winery and Exotic Fruits REF R38 Family owned and operated, visiting The Find just the thing you’re looking for A boutique winery, set on 11 acres of Brewhouse is a must when travelling at Kmart, Coles, Woolworths and over fertile red soil in the hinterland town of LONDON AWARDS, to Bundaberg. -

Rural Towns and Hinterland Areas

FACT SHEET 3 RURAL TOWNS AND HINTERLAND AREAS Council and the community’s vision is for the Bundaberg Region to be “vibrant, progressive, connected and sustainable”. To achieve this vision, Council has prepared the Bundaberg Regional Council Planning Scheme to help manage future land use and development in the Bundaberg Region. The planning scheme aims to strengthen the economy, support local communities, protect and sustainably manage the natural environment and provide targeted investments in infrastructure. The planning scheme provides a framework for sustainable growth management with a time horizon of 2031. This fact sheet has been prepared to provide a summary of the requirements in the planning scheme most relevant to the rural towns and hinterland areas in the Bundaberg Region. Rural Towns and Hinterland Areas Queensland’s Lifestyle Capital The Bundaberg Region covers an area of approximately CHILDERS & GIN GIN – HOUSING CHOICE 6,451 km². Almost 90% of the region forms part of the AND RESIDENTIAL GROWTH rural landscape, incorporating natural environmental The planning scheme provides for a range of housing areas, public open space, forestry and rural production types and densities to accommodate projected growth areas. in the region over the next 20+ years. While most demand for urban growth and residential The rural towns of Childers and Gin Gin provide a development is intended to be concentrated in the range of business, retail, employment and community regional city of Bundaberg and nearby coastal towns, services to their surrounding rural communities, and the planning scheme also provides opportunities also serve as gateways to the region on the Bruce for the growth of rural towns and villages across the Highway. -

Record of Proceedings

PROOF ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/hansard/ E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (07) 3406 7314 Fax: (07) 3210 0182 Subject FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT Page Tuesday, 15 February 2011 MOTION ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Suspension of Standing and Sessional Orders ........................................................................................................................ 1 MOTION ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Natural Disasters ...................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Tabled paper: Proposed Queensland Reconstruction Authority Bill 2011.................................................................... 6 Tabled paper: Proposed Queensland Reconstruction Authority Bill 2011, explanatory notes. .................................... 6 Tabled paper: Bundle of photos of water coming down Toowoomba range. ............................................................. 15 ADJOURNMENT ............................................................................................................................................................................... -

Gin Gin Hospital

Contact Us Wide Bay Gin Gin Monto Bundaberg Hospital Gin Gin Mt Perry Gin Gin, image courtesy of Hervey Bay Childers Sabrina Lauriston/Tourism and Events Queensland Eidsvold Biggenden Mundubbera Maryborough About Gin Gin Gayndah Gin Gin is located in the Bundaberg region. Situated on the Bruce Highway, it lies approximately 50km south-west of Bundaberg and 370km north-west To Gladstone of Brisbane. GIN GIN HOSPITAL Gin Gin must be one of the only towns in Australia King St Elliot St that can link bushrangers, thick scrub, red soil and AplinTce barramundi together through its unique and varied history and landscape. Dear St Bruce Hwy Elliot St Take a trip down Queensland’s pioneering past with May St rural countryside and cattle country, vineyards and olive groves in Gin Gin and surrounds. Gin Gin is a Walker St Milden St To Childers perfect pit stop for travellers heading north or south. To Bundaberg Campbell St With markets in the main street every Saturday, Bundaberg Gin Gin Rd a gallery in the old Courthouse, and international fishing destination Lake Monduran just 20 minutes away, there are plenty of things to see and do. Gin Gin Hospital Country hospitality, The town centre is within walking distance from the 5 King Street, Gin Gin Qld 4671 hospital and has services including a grocery store, Phone: 07 4157 2222 professional health service post office, pharmacy, bank, newsagent, laundromat, bakery, cafes and service stations. Wide Bay Hospital and Health Service respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the land and water on which we work and live.