Historic Preservation Elements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Farm to School Policy Handbook: 2002–2020 Builds on a Survey That Was Originally Released in 2011, and Updated in 2013, 2014, 2017, and 2019

State Farm to School Policy Handbook 2002–2020 Includes state policies introduced between January 2002 and December 2020, as publicly available at the time of the Handbook’s publication. PUBLISHED | JULY 2021 Table of Contents 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 What’s New in this Edition 7 Our Methodology 8 How to Use this Handbook 9 What is Farm to School? 9 Why Farm to School? 10 Why State Farm to School Legislation Matters 11 Key Strategies for Advancing Farm to School through Policy 12 TRENDS IN FARM TO SCHOOL POLICY 15 Overall Look at State Policy Efforts 16 2019–2020 Legislative Trends 19 Emerging Farm to School Opportunities 20 POLICY IN ACTION 21 Promising Practices 23 Advocacy Strategies 28 Next Steps for Advocates 30 CASE STUDIES 31 Local Procurement Incentives: Lessons from the Field 35 Farm to School State Policy Strategies to Support Native Food and Tribal Sovereignty 38 State Policy Responses to COVID-19 Impacting Farm to School 40 BILL SUMMARIES 145 APPENDIX 146 Methodology: The Coding Process 147 Additional Farm to School Resources 148 US Territories 149 2018 Case Studies 149 Hawai‘i 151 Michigan 153 New Mexico 155 US Virgin Islands 157 Vermont 159 State Rankings Chart Acknowledgements This project is funded by the National Agricultural Library, Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture. About the Authors National Farm to School Network has a vision of a strong and just food system for all. We seek deep transformation toward this vision through farm to school – the ways kids eat, grow, and learn about food in schools and early care and education settings. -

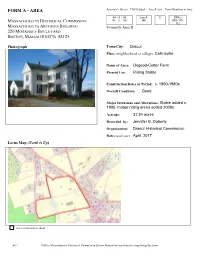

FORM a - AREA Assessor’S Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area

FORM A - AREA Assessor’s Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area 44 – 0 – 99 Lowell, E DRA.2 MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION 44 – 0 – 100 MA DRA.110- 112 MASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES BUILDING Formerly Area B 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Photograph Town/City: Dracut Place (neighborhood or village): Collinsville Name of Area: Osgood-Cutter Farm Present Use: Riding Stable Construction Dates or Period: c. 1850-1980s Overall Condition: Good Major Intrusions and Alterations: Stable added c. 1985, indoor riding arena added 2000s Acreage: 31.34 acres Recorded by: Jennifer B. Doherty Organization: Dracut Historical Commission Date (month/year): April, 2017 Locus Map (North is Up) see continuation sheet 4 / 1 1 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM A CONTINUATION SHEET DRACUT OSGOOD-CUTTER FARM MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area Letter Form Nos. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 B DRA.2, DRA.110-112 Recommended for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. If checked, you must attach a completed National Register Criteria Statement form. Use as much space as necessary to complete the following entries, allowing text to flow onto additional continuation sheets. ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION Describe architectural, structural and landscape features and evaluate in terms of other areas within the community. The Osgood-Cutter Farm includes a historic c. 1850 house as well as more recent buildings related to its use as a riding stable. The c. 1850 Atis Osgood House, 746 Mammoth Road, is a two-story T-plan building composed of two gabled sections set perpendicular to each other, forming a T. -

The New Hampshire Barn Survey Began Three Years

THE NEW HAMPSHIRE BARN SURVEY Elizabeth H. Muzzey, State Survey Coordinator The New Hampshire property owner, and by checking the Barn Survey began three years ago, town history and old photographs – a when the NH Division of Historical tall order for just one person. With Resources and the Historic Agricultural practice over a year and a half, the team Structures Advisory Committee kicked devoted an average of three hours to off a farm reconnaissance inventory every barn, including fieldwork and project. assembling the inventory form in its The Advisory Committee was final format. formed the year before, with the The historical society legislative charge to slow the loss of advertised the barn survey in the local New Hampshire’s historic agricultural newspaper to let property owners know structures – barns, silos, corn cribs, WALLACE FARM (PIONEER FARM) what was happening. Although some poultry houses and more – by helping COLUMBIA, NH property owners initially worried that property owners preserve these Photograph by Christine E. Fonda the project was somehow related important cultural landmarks. The barn property to tax assessments (a common survey was initiated to determine how Francestown fear for any historical survey work!), the many and what types of agricultural The Francestown Historical society found that most everyone was buildings remained in the state Society was among the first to contact thrilled that the town’s agricultural In the past three years, the Division of Historical Resources for buildings were being cataloged. hundreds of barn owners from every ideas on how to complete a town-wide Recently, “many properties have rapidly part of New Hampshire have completed barn survey. -

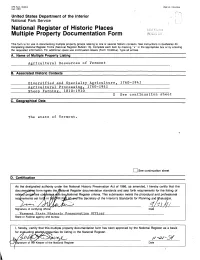

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 7024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service , ., . .Ii {: National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ______Agricultural Resources of Vermont_________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts__________________________________________ ______Diversified and Specialty Agriculture, 1760-1941___________ ______Agricultural Processing, 1760-1941________________________ ______Sheep Farming, 1810-1910____________________________ —————— jr See continuation sheet C. Geographical Data The state of Vermont. I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documerjtaten form meets the J&tional Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of relatpdprqpenies coijis/istep* wfti thejNational Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set for$ in /^pFR Pj^jB£l-a«d*the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. kl— Signature of certifying official Vermont: State Hi stnrn _c. Preservation Officer State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating celateckproperties for listing in the National Register. ignature of tHe Keeper of the National Register Date NFS Form 1MOO* 0MB Appnvtl No. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms lies? Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Harrisville Rural District and/or common street & number not for publication city, town Harrisville __ vicinity of state New Hampshire code 33 county Cheshire code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use _X_ district public X occupied _ X_ agriculture museum building(s) _x_ private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible __ entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation __ no __ military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple (see attached listings) street & number city, town __ vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. r.hP<;rn>P r.nnnty CnnrthniisP - Rpg-Utry nf street & number Court Street city, town Keene state New Hampshi re 6. Representation in Existing Surveys:^] Determination of Eligibility: title Harrisvilie Rural District has this property been determined eligible? _X_yes no date August, 1982 J<_ federal state county depository for survey records Department of the Interior city, town Washington state 7. Description Condition , Check one Check one -

National Register of Historic Places Received 3 N Inventory Nomination

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register of Historic Places received 3 n Inventory Nomination Form date entered FEB 27 1986 See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________________________________ 1. Name historic William Boyd House and/or common GENERAL MASON J. YOUNG HOUSE (preferred) 2. Location n/a not for publication city, town Londonderry n/a vicinity of state New Hampshire code 33 county Rockingham code 015 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational X private residence site Public .Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted __ government scientific being considered _ X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation X N/A no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Col. Mason James Young, Jr.. U.S. Armv.Retired 4 Young Road * street & number 716 Plymouth Circle ** Londonderry * New Hampshire 03053 city, town Newport News ** state Virginia 23602 Summer address 5. Location of Legal Description\ address________ courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Rockingham County Courthouse Rockingham County Registry of Deeds street & number Hampton Road city, town Exeter, state New Hampshire 03833 6. Representation in Existing Surveys y title None has this property been determined eligible? yes _±>no date N/A federal state county __ local city, town N/A state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one X excellent deteriorated X unaltered X original site good ruins altered moved date N/A fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The William Boyd House is a rectangular wood-frame dwelling .of two stories with a series of connected outbuildings. -

A Geographical History of Rural Development in Nineteenth-Century Oxford County

Maine History Volume 42 Number 3 Oxford County's Bicentennial, 1805 - Article 4 2005 10-1-2005 Buckfield: A Geographical History of Rural Development in Nineteenth-Century Oxford County Nancy Hatch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hatch, Nancy. "Buckfield: A Geographical History of Rural Development in Nineteenth-Century Oxford County." Maine History 42, 3 (2005): 158-170. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/ mainehistoryjournal/vol42/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. H .V /J/'/: /! .'/*/*•+ 2 o O tU *i< •trt fro. 4 - o /> i\ul t rr/1 flit \ ■ . J if' A-*/. ✓, V ■ ><»■»» . w /w»«v. ■ ' 5 ' - *. VWc4 •K //C ■*.. j . - M fv / t m t\ / o h % o r \ o J j ) » 0 5 » * J . u m H4 HW . d T- • I' ■ 43 ■■■■ / * 1 ...lt>. ' .11 O 2< is S y lt r s / r r V, ('•tnodtt r5& 2w . | . ■_ 2? V U 1*j * 70’ > V./,, />>/#/ ^ ■*> Map 1. John Jordan’s 1785 survey map shows the disbursed nature of early set tlement in Buckfield. Over the next half-century, the town’s business and cul tural establishments were drawn to the center of town, which only then began to resemble the archetypical “New England village.” Map courtesy of the author. -

Historic District Area Name: Antrim Center

New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources Page 1 of 43 AREA FORM: HISTORIC DISTRICT AREA NAME: ANTRIM CENTER 1. Type of Area Form 8. UTM reference: Town-wide: Historic District: 9. Inventory numbers in this area: Project Area: ANT0005 2. Name of area: Antrim Center 10. Setting: Small agrarian residential village at the foot of Meetinghouse Hill 3. Location: Residential village located at that developed in the eighteenth and the foot of Meetinghouse Hill on the nineteenth centuries. intersection of present-day Clinton and Meetinghouse Hill roads 11. Acreage: Approximately 88 acres 4. City or town: Antrim 12. Preparer(s): Russell Stevenson, Architectural Historian 5. County: Hillsborough 13. Organization: A.D. Marble & 6. USGS quadrangle name(s): Hillsboro Company 7. USGS scale: 1:2000 14. Date(s) of field survey: November 2011 15. Location map New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources Page 2 of 43 AREA FORM: HISTORIC DISTRICT AREA NAME: ANTRIM CENTER 16. Sketch map – See the following continuation sheets for the sketch map (Figure 1) and additional figures. New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources Page 3 of 43 AREA FORM: HISTORIC DISTRICT AREA NAME: ANTRIM CENTER 17. Methods and Purpose The purpose of this historic district area form is to document the development of Antrim Center in order to assess its eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places. Antrim Center is located within the 3-mile viewshed (Area of Potential Effect [APE]) of the proposed Antrim Wind Energy Project (MLT- ANTW). Antrim Wind Energy LLC proposes to develop a utility scale wind energy generation facility in the Town of Antrim, Hillsborough County, New Hampshire. -

Maine's Connected Farm Buildings, Part II

Maine History Volume 18 Number 4 Article 4 4-1-1979 Maine's Connected Farm Buildings, Part II Thomas C. Hubka University of Oregon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hubka, Thomas C.. "Maine's Connected Farm Buildings, Part II." Maine History 18, 4 (1979): 217-245. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol18/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THOMAS C. HUBKA MAINE’S CONNECTED FARM BUILDINGS* Part II ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE The picturesque visual variety of Maine’s connected farms conceals a uniform arrangement of buildings. The prototypal organization for a fully connected house-to- barn structure consists of four distinct areas or general building types. A children’s rhyme from the last century records the principal organizational components: “Big house, little house, back house, barn”1 (Fig. 1). This organizational scheme became the dominant arrangement for farm buildings in northern New England in the late nineteenth century and continued to influence farm construction into the twentieth century when it was only gradually replaced by a farm building arrangement employing detached agricultural buildings. Big House - Front, Main or Farmhouse This building is the principal dwelling and symbol of home for the farm. It may be constructed in many house *This is the second of a two part series. -

BELMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY - JULY 19Th 2016 PROGRAM

BELMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY - JULY 19th 2016 PROGRAM: “BIG HOUSE, LITTLE HOUSE, BACK HOUSE, BARN: the Connected Farm Buildings of New England” On Tuesday, July 19th, at 7 PM, Prof. Thomas Hubka, will present the program, “Big House, Little House, Back House, Barn: the Connected Farm Buildings of New England” at the Corner Meeting House in Belmont, NH. This program is hosted by the Belmont Historical Society and funded through NH Humanities. It is an illustrated talk that focuses on the four essential components of nineteenth-century NE farms and discusses how and why the farmers converted their typical separate house and barns into connected farmsteads. Many of these beautiful, stately farmsteads still exist today and offer insight into the lives of the people who developed them. Prof. Hubka's discussion follows the connected farm movement and demonstrates that the average NE farmer was motivated into developing this style of architecture as a means to supplement farm income, as they faced competition with farmers in other regions of America who had better soils and growing conditions. Prof. Hubka’s award- winning book on the subject of connected farm buildings will be available for those wishing more in-depth information regarding the historical development of connected buildings in New England. Thomas C. Hubka is a Professor Emeritus from the Department of Architecture, Typical connected farm building and room arrangement. Sawyer-Black Farm, Sweden, University of Wisconsin−Milwaukee Maine. (excerpt from book, p.7) where he taught for over twenty years. His presentation focuses on the historical development of New Hampshire’s farm architecture. -

Farmstead and Household Archaeology at the Barrett Farm

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 6-2011 Farmstead and Household Archaeology at the Barrett aF rm, Concord, Massachusetts Thomas P. Mailhot University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Mailhot, Thomas P., "Farmstead and Household Archaeology at the Barrett aF rm, Concord, Massachusetts" (2011). Graduate Masters Theses. Paper 34. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FARMSTEAD AND HOUSEHOLD ARCHAEOLOGY AT THE BARRETT FARM, CONCORD, MASSACHUSETTS A Thesis Presented by THOMAS P. MAILHOT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts, Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS June 2011 Historical Archaeology Program © 2011 by Thomas P. Mailhot All rights reserved HOUSEHOLD AND FARMSTEAD ARCHAEOLOGY AT THE BARRETT FARM, CONCORD, MASSACHUSETTS A Thesis Presented by Thomas P. Mailhot Approved as to style and content by: ________________________________________________ David Landon, Associate Director of the Fiske Center Chairperson of Committee ________________________________________________ Christa Beranek, Research Scientist at the Fiske Center Member ________________________________________________ Heather Trigg, Research Scientist at the Fiske Center Member _________________________________________ Stephen Silliman, Program Director Historical Archaeology Program _________________________________________ Judith Zeitlin, Chairperson Anthropology Department ABSTRACT FARMSTEAD AND HOUSEHOLD ARCHAEOLOGY AT THE BARRETT FARM, CONCORD, MASSACHUSETTS June 2011 Thomas P. -

Historic District

New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources Page 1 of 93 AREA FORM BEDFORD CENTER HISTORIC DISTRICT 1. Type of Area Form Inventory numbers in this area: Town-wide: NHDOT: NH Route 101 & Wallace Rd Area Form Historic District: (1992) Project Area: BED0004, 0062, 0074, 0074A (1992) BED0026-0040 (2013) Name of area: Bedford Center Setting: 3. Location: approximately 5 miles southwest Upland suburban setting of rolling hills, drained by of downtown Manchester on NH Route 101 Riddle Brook and tributary of Patten Brook, approximately 2 miles west of the Merrimack City or town: Bedford River. Characterized by an 18th-century village center with church, town hall, library and cemetery County: Hillsborough at a six-way crossroads. Roads radiating from the center feature residential properties dating from the mid-18th century to the present with most larger USGS quadrangle name(s): Pinardville, N.H. tracts (former farms) subdivided and developed during the past 60+/- years with low-density USGS scale: 1:24,000 suburban housing on wooded lots. Present-day agricultural activity is minimal. UTM reference: Acreage: approx. 207 acres 1. 19 293550E 4757756N 2. 19 293817E 4757892N 3. 19 293907E 4757647N Preparer(s): Patrick Harshbarger, Principal 4. 19 294258E 4757832N Historian, and Alison Haley, Architectural 5. 19 294186E 4758069N Historian, Hunter Research, Inc. 6. 19 294350E 4758078N 7. 19 295289E 4759093N Organization: Prepared for New Hampshire 8. 19 295360E 4759100N Department of Transportation, NH Route 101 9. 19 295398E 4758970N Widening Project 10. 19 294927E 4757820N 11. 19 294614E 4757564N Date(s) of field survey: December 2013 12. 19 294152E 4757297N 13.