Comics' Reception As Literature and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Knight Manual: Tools, Weapons, Vehicles & Documents from the Batcave, 2012, Brandon T

The Dark Knight Manual: Tools, Weapons, Vehicles & Documents from the Batcave, 2012, Brandon T. Snider, 1781162859, 9781781162859, Titan Publishing Group, 2012 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/16SXNyt http://www.amazon.com/s/?url=search-alias=stripbooks&field-keywords=The+Dark+Knight+Manual%3A+Tools%2C+Weapons%2C+Vehicles+%26+Documents+from+the+Batcave In 2005, filmmaker Christopher Nolan redefined Batman for a new generation with "Batman Begins," followed in 2008 by "The Dark Knight," and now 2012's conclusion to the trilogy, "The Dark Knight Rises." Here, for the first time, is an in-world exploration of Christopher Nolan's Batman: "The Dark Knight Manual," the definitive guide to his tools, vehicles, and technologies. Following the destruction of Wayne Manor, Bruce Wayne began to assemble key sketches, diagrams, observations, and other top-secret documents germane to becoming Batman; he then entrusted this manual to his faithful butler, Alfred. Every defining moment is detailed here, charting Wayne's collaborations with Lucius Fox at Wayne Enterprises on the latest cutting-edge technology. Featuring removable documents, including the design and capability of the famed utility belt, the hi-tech functions of Batman's cowl, and every detail of his amazing arsenal of weapons and gadgets, "The Dark Knight Manual" reveals how Bruce Wayne operates as Gotham's greatest protector. BATMAN and all related characters and elements are trademarks of and (c) DC Comics. (s12) DOWNLOAD http://tiny.cc/tzpBvm http://bit.ly/1veOZsX The Dark Knight Rises: I Am Bane , Lucy Rosen, Jun 5, 2012, Juvenile Fiction, 24 pages. Bane is a super-villain with a bad attitude. -

Drawing on the Victorians Eries in Victorian Studies S Series Editors: Joseph Mclaughlin and Elizabeth Miller Katherine D

Drawing on the Victorians eries in Victorian Studies S Series editors: Joseph McLaughlin and Elizabeth Miller Katherine D. Harris, Forget Me Not: The Rise of the British Literary Annual, 1823–1835 Rebecca Rainof, The Victorian Novel of Adulthood: Plot and Purgatory in Fictions of Maturity Erika Wright, Reading for Health: Medical Narratives and the Nineteenth-Century Novel Daniel Bivona and Marlene Tromp, editors, Culture and Money in the Nineteenth Century: Abstracting Economics Anna Maria Jones and Rebecca N. Mitchell, editors, Drawing on the Victorians: The Palimpsest of Victorian and Neo-Victorian Graphic Texts Drawing on the Victorians The Palimpsest of Victorian and Neo-Victorian Graphic Texts edited by Anna Maria Jones and Rebecca N. Mitchell with an afterword by Kate Flint ohio university press athens Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701 ohioswallow.com © 2017 by Ohio University Press All rights reserved To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax). Printed in the United States of America Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ƒ ™ 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request. Names: Jones, Anna Maria, 1972- editor. | Mitchell, Rebecca N. (Rebecca Nicole), 1976- editor. Title: Drawing on the Victorians : the palimpsest of Victorian and neo-Victorian graphic texts / edited by Anna Maria Jones and Rebecca N. Mitchell ; with an afterword by Kate Flint. -

Star Wars Insider Nov 2018 (Usps 003-027) (Issn 1041-5122)

UP TO SPEED: THE GALACTIC HOT RODS OF STAR WARS TARKIN ™ THE HORROR STAR BEHIND STAR WARS’ THEH E OFFICIALOFF FFII CCII A L MAGAZINEMAGAZINI N E FINEST VILLAIN! + WIN! A STAR WARS PRIZE WORTH $400! DROID UPRISING! L3-37 leads the fi ght for freedom! JON KASDAN Exclusive interview with the co-writer of Solo: A Star Wars Story! SHOOTING SOLO Behind the scenes on the making of the smash-hit movie! IN CONCERT Star Wars goes live with the London Symphony Orchestra! GALACTIC GEOGRAPHIC: EXPLORING THE COLORFUL worlds of STAR WARS A MESSAGE FROM THE EDITOR ™ NOV 2018 TITAN EDITORIAL Editor / Chris Cooper Senior Editor / Martin Eden WELCOME... Assistant Editors / Tolly Maggs, Jake Devine Art Editor / Andrew Leung Whenever you hear the first note of John Williams’ LUCASFILM Star Wars main title theme, I’m willing to bet that the Senior Editor / Brett Rector hairs on the back of your neck still tingle. That opening Art Director / Troy Alders Creative Director / Michael Siglain fanfare triggers so many fond memories for me, often Asset Management / Tim Mapp, entirely unrelated to actually watching one of the movies. Erik Sanchez, Bryce Pinkos, For those of us ancient enough to remember vinyl Nicole LaCoursiere, Shahana Alam Story Group / Pablo Hidalgo, Leland Chee, records before hyper-cool hipsters and audiophiles Matt Martin brought them back, the Star Wars Original Soundtrack CONTRIBUTORS album was a very special thing—it was literally the closest Tricia Barr, Tara Bennett, Natalie Clubb, you could get to experiencing the film at home, the tracks Megan Crouse, Michael Kogge, Tom Miller, on that double-LP a visceral link to the movie itself. -

Video 108 Media Corp 9 Story A&E Networks A24 All Channel Films

Video 108 Media Corp 9 Story A&E Networks A24 All Channel Films Alliance Entertainment American Cinema Inspires American Public Television Ammo Content Astrolab Motion Bayview Entertainment BBC Bell Marker Bennett-Watt Entertainment BidSlate Bleecker Street Media Blue Fox Entertainment Blue Ridge Holdings Blue Socks Media BluEvo Bold and the Beautiful Brain Power Studio Breaking Glass BroadGreen Caracol CBC Cheng Cheng Films Christiano Film Group Cinedigm Cinedigm Canada Cinema Libre Studio CJ Entertainment Collective Eye Films Comedy Dynamics Content Media Corp Culver Digital Distribution DBM Films Deep C Digital DHX Media (Cookie Jar) Digital Media Rights Dino Lingo Disney Studios Distrib Films US Dreamscape Media Echelon Studios Eco Dox Education 2000 Electric Entertainment Engine 15 eOne Films Canada Epic Pictures Epoch Entertainment Equator Creative Media Everyday ASL Productions Fashion News World Inc Film Buff Film Chest Film Ideas Film Movement Film UA Group FilmRise Filmworks Entertainment First Run Features Fit for Life Freestyle Digital Media Gaiam Giant Interactive Global Genesis Group Global Media Globe Edutainment GoDigital Inc. Good Deed Entertainment GPC Films Grasshopper Films Gravitas Ventures Green Apple Green Planet Films Growing Minds Gunpowder & Sky Distribution HG Distribution Icarus Films IMUSTI INC Inception Media Group Indie Rights Indigenius Intelecom Janson Media Juice International KDMG Kew Media Group KimStim Kino Lorber Kinonation Koan Inc. Language Tree Legend Films Lego Leomark Studios Level 33 Entertainment -

Title of Book/Magazine/Newspaper Author/Issue Datepublisher Information Her Info

TiTle of Book/Magazine/newspaper auThor/issue DaTepuBlisher inforMaTion her info. faciliT Decision DaTe censoreD appealeD uphelD/DenieD appeal DaTe fY # American Curves Winter 2012 magazine LCF censored September 27, 2012 Rifts Game Master Guide Kevin Siembieda book LCF censored June 16, 2014 …and the Truth Shall Set You Free David Icke David Icke book LCF censored October 5, 2018 10 magazine angel's pleasure fluid issue magazine TCF censored May 15, 2017 100 No-Equipment Workout Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 of the Most Beautiful Women in Painting Ed Rebo book HCF censored February 18, 2011 100 Things You Will Never Find Daniel Smith Quercus book LCF censored October 19, 2018 100 Things You're Not Supposed To Know Russ Kick Hampton Roads book HCF censored June 15, 2018 100 Ways to Win a Ten-Spot Comics Buyers Guide book HCF censored May 30, 2014 1000 Tattoos Carlton Book book EDCF censored March 18, 2015 yes yes 4/7/2015 FY 15-106 1000 Tattoos Ed Henk Schiffmacher book LCF censored December 3, 2007 101 Contradictions in the Bible book HCF censored October 9, 2017 101 Cult Movies Steven Jay Schneider book EDCF censored September 17, 2014 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genius Brad Graham & Kathy McGowan book HCF censored August 31, 2011 yes yes 9/27/2011 FY 12-009 110 Years of Broadway Shows, Stories & Stars: At this Theater Viagas & Botto Applause Theater & Cinema Books book LCF censored November 30, 2018 113 Minutes James Patterson Hachette books book -

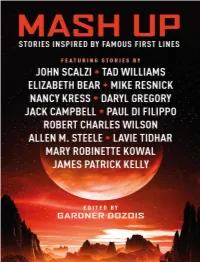

Mash up Print Edition ISBN: 9781785651038 E-Book Edition ISBN: 9781785651045

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS Wastelands 2 Tales of the apocalypse Dead Man’s Hand An anthology of the weird West Encounters of Sherlock Holmes Stories of the great detective Further Encounters of Sherlock Holmes Twelve brand-new adventures Mash Up Print edition ISBN: 9781785651038 E-book edition ISBN: 9781785651045 Published by Titan Books A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd 144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP First edition: June 2016 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. “Introduction” © 2016 by Steve Feldberg. “Fireborn” © 2016 by Robert Charles Wilson. “The Evening Line” © 2016 by Mike Resnick. “No Decent Patrimony” © 2016 by Elizabeth Bear. “The Big Whale” © 2016 by Allen M. Steele. “Begone” © 2016 by Daryl Gregory. “The Red Menace” © 2016 by Lavie Tidhar. “Muse of Fire” © 2016 by John Scalzi. “Writer’s Block” © 2016 by Nancy Kress. “Highland Reel” © 2016 by John G. Hemry. “Karen Coxswain, Or, Death As She Is Truly Lived” © 2016 by Paul Di Filippo. “The Lady Astronaut Of Mars” © 2016 by Mary Robinette Kowal. “Every Fuzzy Beast Of The Earth, Every Pink Fowl Of The Air” © 2016 by Tad Williams. “Declaration” © 2016 by James Patrick Kelly. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Cognotes May Preview Edition

COGNOTES MAY PREVIEW EDITION CHICAGO, IL AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Reshma Saujani, Girls Who Code Founder, CEO to Open 2017 ALA Annual Conference ince 2012, Girls Who Code has followers. The forthcoming book Girls Who taught computing skills to and in- Reshma Saujani Code: Learn to Code and Change the World spired more than 10,000 girls across Opening General Session (August 2017, ages 10 and up), will show S Friday 6/23, 4:00 – 5:15 p.m. America – and they are just at the beginning girls how coding skills are relevant to their of their mission to close the gender gap lives and will get them excited about creating in tech. Reshma Saujani, the founder and Girls Who Code is growing fast, with a their own apps, games, and robots. With dy- CEO of the national nonprofit organization, goal of reaching one million young women namic artwork, down-to-earth explanations is also the author of the groundbreaking by 2020. 1.4 million jobs will be open in of coding principles, and real-life stories of book Women Who Don’t Wait In Line, in computing related fields in the U.S., of girls and women working at places like Pixar which she advocates for a new model of which we are only on pace to fill 29 per- and NASA, it sets out to prove that coding is female leadership focused on embracing cent with computing graduates, a mere 3 truly for everyone, no matter their interests. risk and failure, promoting mentorship and percent of whom are likely to be women. -

29Oct2019 Missouri Department of Corrections Censored Publications (2012 - Current)

Prepared for Sunshine Law Request - 29Oct2019 Missouri Department of Corrections Censored Publications (2012 - Current) Sender Name Volume/Issue Sender Address Final Date Entered Title of Publication Publisher Name Publisher Address (if different from Reason for Censorship Number (if different from publisher) Decision publisher) No conflict - Censor (pages 62-64, 76-79 (but 1 Barnes and Noble Way Thursday, August 09, 2012 Reflected In You paperback book The Berkley Publishing Group 375 Hudson Street New York, NY 10014 Barnes & Noble not limited to) contains sexually explicit Censor Monroe TWP NJ 08831 material) No conflict - Censor (Mailing Algoa Friday, December 21, 2012 Cold Crib Issue #2 Cold Crib PO Box 682407, Franklin, TN 37068 Correctional Centerompanied by 2 nude Censor photos-thong style underwear) No conflict - Censor (Shows explicit sex acts, PO Box 420235 pgs 46, 91, 94, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 130 & Friday, December 21, 2012 Penthouse Jan 13 Penthouse Censor Palm Coast FL 32142-0235 142; story on distributing, selling & packaging marijuana pgs 58-63) Zane Presents The A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1230 129 31st Street No conflict - Censor (Explicit Sex, pgs 4-12, Friday, December 21, 2012 Eroticanoir.com Anthology: n/a Atria Books Avenue of the Americas, New York, New Music by Mail Censor Brooklyn NY 11232 22-23, 29-37, 57, 103; etc.) Succulent Chocolate Flava II York 10020 Capital Gains The People, One Chamber Plaza; Little Rock, AR No conflict - Censor (Contains Oversized Wednesday, December 26, 2012 Place and Purpose of Little n/a Censor 72201 Map) Rock and the Region Censored by Deputy Division Directors 4000 Shoreline Court, Suite 400 01/22/13 due to promotion of violence (p. -

GRANT MORRISON Great Comics Artists Series M

GRANT MORRISON Great Comics Artists Series M. Thomas Inge, General Editor Marc Singer GRANT MORRISON Combining the Worlds of Contemporary Comics University Press of Mississippi / Jackson www.upress.state.ms.us The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses. Copyright © 2012 by University Press of Mississippi All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing 2012 ∞ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Singer, Marc. Grant Morrison : combining the worlds of contemporary comics / Marc Singer. p. cm. — (Great comics artists series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61703-135-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 1-61703-136-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-61703-137-3 (ebook) 1. Morrison, Grant—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Comic books, strips, etc.—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN6727.M677Z86 2012 741.5’973—dc22 2011013483 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available Contents vii Acknowledgments 3 Introduction: A Union of Opposites 24 CHAPTER ONE Ground Level 52 CHAPTER TWO The World’s Strangest Heroes 92 CHAPTER THREE The Invisible Kingdom 136 CHAPTER FOUR Widescreen 181 CHAPTER FIVE Free Agents 221 CHAPTER SIX A Time of Harvest 251 CHAPTER SEVEN Work for Hire 285 Afterword: Morrison, Incorporated 293 Notes 305 Bibliography 317 Index This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This book would not have been possible without the advice and support of my friends and colleagues. Craig Fischer, Roger Sabin, Will Brooker, and Gene Kannenberg Jr. generously gave their time to read the manuscript and offer feedback. Joseph Witek, Jason Tondro, Steve Holland, Randy Scott, the Michigan State University Library Special Collections, and the George Washington University Gelman Library provided me with sources and images. -

American Second World War Comics and Propaganda

Heroes and Enemies: American Second World War Comics and Propaganda Andrew Kerr A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. July 2016 1 Contents: Dedication – p. 3 Acknowledgements – p. 4 Abstract – p. 5 Introduction – p. 8 Comics as a Source – p. 21 Methodology – p. 26 Literature Review – p. 33 Comics and Propaganda – p. 41 Humour – p. 47 Heroes and Enemies – p. 51 The Physiognomy and Ideology of the Hero and Enemy – p. 62 Myth and the American Dream – p. 67 Mythic Criticism – p. 72 Stereotypes and Role Models – p. 76 Chapter One: Comics, Propaganda and the Office of War Information – p. 83 The Value of Comics As Advertising Media – p. 85 Comics, Publishers and the OWI – p. 90 The Hero and Enemy in ‘Report 15’ – p. 105 Chapter Conclusion – p. 107 Chapter Two: Types of Hero in Second World War American Comics – p. 110 The Political Hero – p. 112 Attributes of the Political Hero: Foreign Language Acquisition – p. 115 Attributes of the Political Hero: Sport and Horsemanship – p. 119 Attributes of the Political Hero: Foresight – p. 123 Attributes of the (Foreign) Political Hero: Recklessness – p. 127 The Soldier Hero – p. 131 Spectacular Violence – p. 140 The Symbolic Hero – p. 151 The Cooperation of the Categories of the Hero – p. 163 Unpublished Second World War Comics By Members of the United States Armed Forces – p. 168 Chapter Conclusion – p. 182 Chapter Three: Types of Enemy in Second World War American Comics – p. 195 Ideological Enemies – p. 190 Enemy Leaders – p. -

`` Vertigo's British Invasion '': La Revitalisation Par Les Scénaristes

“ Vertigo’s British Invasion ” : la revitalisation par les scénaristes britanniques des comic books grand public aux Etats-Unis (1983-2013) Isabelle Licari-Guillaume To cite this version: Isabelle Licari-Guillaume. “ Vertigo’s British Invasion ” : la revitalisation par les scénaristes britan- niques des comic books grand public aux Etats-Unis (1983-2013). Littératures. Université Michel de Montaigne - Bordeaux III, 2017. Français. NNT : 2017BOR30044. tel-01757263 HAL Id: tel-01757263 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01757263 Submitted on 3 Apr 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. École doctorale Montaigne Humanités, ED 480 Laboratoire CLIMAS, EA 4196 Cultures et Littératures des Mondes Anglophones Thèse de doctorat en Études Anglophones VERTIGO’S BRITISH INVASION : La revitalisation par les scénaristes britanniques des comic books grand public aux États-Unis (1983-2013) Thèse présentée et soutenue publiquement le 8 décembre 2017 par Isabelle LICARI-GUILLAUME Sous la direction de M. le Professeur Jean-Paul GABILLIET Membres du Jury Mme Françoise BESSON, Professeur, Université Toulouse 2 – Jean Jaurès M. Jean-Paul GABILLIET, Professeur, Université Bordeaux Montaigne M. Laurence GROVE, Professeur, Université de Glasgow Mme Vanessa GUIGNERY, Professeur, Ecole normale supérieure de Lyon M. -

Graphic Novel Finding Aid for Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation & Fantasy Last Updated: September 15, 2020

Graphic Novel Finding Aid for Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation & Fantasy Last updated: September 15, 2020 Most books in this list are in English. We have some graphic novels in other languages . Books are listed alphabetically by series title. Books in series are listed in numerical order (if possible) — otherwise they’re listed alphabetically by sub-title. A | B |C |D | E |F |G | H | I| J| K | L | M | N |O | P | Q| R |S | T| U | V | W | X | Y | Z Title Writer/Artist Notes A A.B.C. Warriors. The Mills, Pat and Kevin A.B.C. Warriors began in Mek-nificent Seven O’Neill and Mike Starlord. McMahon A. D.: after death Snyder, Scott and Jeff Lemire A.D.D. : Adolescent Rushkoff, Douglas Demo Division et al. Aama. 1, The smell Peeters, Frederick of warm dust Aama. 2, The Peeters, Frederick invisible throng Aama. 3, The desert Peeters, Frederick of mirrors The Abaddon Shadmi, Koren Abbott Ahmed, Saladin and Originally published in single others magazine form as Abbott, #1-5. Aama. 4, You will be Peeters, Frederick glorious, my daughter Abe Sapien. Vol. 1, Mignola, Mike et al. The drowning Abe Sapien. Vol. 2, Mignola, Mike et al. The devil does not jest and other stories Across the Universe. Moore, Alan et al. “Superman annual” #11; The DC Universe “Detective comics” #549, 550, stories of Alan “Green Lantern” #188; Moore “Vigilante” #17, 18; “The Omega men” #26, 27; “DC Comics presents” #85; “Tales of the Green Lantern corps annual” #2, 3; “Secret origins” #10; “Batman annual” #11 The Action heroes Gill, Joe et al.