Enabling Inclusive and Sustainable Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class of 1964 Th 50 Reunion

Class of 1964 th 50 Reunion BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY 50th Reunion Special Thanks On behalf of the Offi ce of Development and Alumni Relations, we would like to thank the members of the Class of 1964 Reunion Committee Joel M. Abrams, Co-chair Ellen Lasher Kaplan, Co-chair Danny Lehrman, Co-chair Eve Eisenmann Brooks, Yearbook Coordinator Charlotte Glazer Baer Peter A. Berkowsky Joan Paller Bines Barbara Hayes Buell Je rey W. Cohen Howard G. Foster Michael D. Freed Frederic A. Gordon Renana Robkin Kadden Arnold B. Kanter Alan E. Katz Michael R. Lefkow Linda Goldman Lerner Marya Randall Levenson Michael Stephen Lewis Michael A. Oberman Stuart A. Paris David M. Phillips Arnold L. Reisman Leslie J. Rivkind Joe Weber Jacqueline Keller Winokur Shelly Wolf Class of 1964 Timeline Class of 1964 Timeline 1961 US News • John F. Kennedy inaugurated as President of the United World News States • East Germany • Peace Corps offi cially erects the Berlin established on March Wall between East 1st and West Berlin • First US astronaut, to halt fl ood of Navy Cmdr. Alan B. refugees Shepard, Jr., rockets Movies • Beginning of 116.5 miles up in 302- • The Parent Trap Checkpoint Charlie mile trip • 101 Dalmatians standoff between • “Freedom Riders” • Breakfast at Tiffany’s US and Soviet test the United States • West Side Story Books tanks Supreme Court Economy • Joseph Heller – • The World Wide decision Boynton v. • Average income per TV Shows Catch 22 Died this Year Fund for Nature Virginia by riding year: $5,315 • Wagon Train • Henry Miller - • Ty Cobb (WWF) started racially integrated • Unemployment: • Bonanza Tropic of Cancer • Carl Jung • 40 Dead Sea interstate buses into the 5.5% • Andy Griffi th • Lewis Mumford • Chico Marx Scrolls are found South. -

Accelerating Development Using the Web: Empowering Poor and Marginalized Populations George Sadowsky, Ed

Accelerating Development Using the Web: Empowering Poor and Marginalized Populations George Sadowsky, ed. George Sadowsky Najeeb Al-Shorbaji Richard Duncombe Torbjörn Fredriksson Alan Greenberg Nancy Hafkin Michael Jensen Shalini Kala Barbara J. Mack Nnenna Nwakanma Daniel Pimienta Tim Unwin Cynthia Waddell Raul Zambrano Cover image: Paul Butler http://paulbutler.org/archives/visualizing-facebook-friends/ Creative Commons License Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 This work, with the exception of Chapter 7 (Health), is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Chapter 7 (Health) © World Health Organization [2012]. All rights reserved. The World Health Organization has granted the Publisher permission for the reproduction of this chapter. Accelerating Development Using the Web | Foreword from the Rockefeller Foundation i Foreword from the Rockefeller Foundation For almost 100 years, the Rockefeller Foundation has been at the forefront of new ideas and innovations related to emerging areas of technology. In its early years, the Foundation advanced new technologies to eradicate hookworm and develop a vaccine for yellow fever, creating a lasting legacy of strengthening the application of new technologies to improve the lives of the world’s poor and vulnerable. By the middle of the 20th century, this approach led the Foundation to the pre-cursor to the modern day comput- er. At the dawn of the digital era in 1956, the Foundation helped launch the field of artificial intelligence through its support for the work of John McCarthy, the computing visionary who coined the term. -

Update 6: Internet Society 20Th Anniversary and Global INET 2012

Update 6: Internet Society 20th Anniversary and Global INET 2012 Presented is the latest update (edited from the previous “Update #6) on the Global INET 2012 and Internet Hall of Fame. Executive Summary By all accounts, Global INET was a great success. Bringing together a broad audience of industry pioneers; policy makers; technologists; business executives; global influencers; ISOC members, chapters and affiliated community; and Internet users, we hosted more than 600 attendees in Geneva, and saw more than 1,300 participate from remote locations. Global INET kicked off with our pre‐conference programs: Global Chapter Workshop, Collaborative Leadership Exchange and the Business Roundtable. These three programs brought key audiences to the event, and created a sense of energy and excitement that lasted through the week. Of key importance to the program was our outstanding line‐up of keynotes, including Dr. Leonard Kleinrock, Jimmy Wales, Francis Gurry, Mitchell Baker and Vint Cerf. The Roundtable discussions at Global INET featured critical topics, and included more than 70 leading experts engaged in active dialogue with both our in‐room and remote audiences. It was truly an opportunity to participate. The evening of Monday 23 April was an important night of celebration and recognition for the countless individuals and organizations that have dedicated time and effort to advancing the availability and vitality of the Internet. Featuring the Internet Society's 20th Anniversary Awards Gala and the induction ceremony for the Internet Hall of Fame, the importance of the evening cannot be understated. The media and press coverage we have already received is a testament to the historic nature of the Internet Hall of Fame. -

The Global Gender Digital Divide and Its Implications for Women’S Human Rights and Equality

TREUTHART 02.27.20 330 PM FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 3/13/20 2:12 PM CONNECTIVITY: THE GLOBAL GENDER DIGITAL DIVIDE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR WOMEN’S HUMAN RIGHTS AND EQUALITY Mary Pat Treuthart* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 2 II. BENEFITS OF WOMEN’S MEANINGFUL AND SUBSTANTIAL ACCESS TO ICTS .................................................................................................... 5 A. Economic and Educational Empowerment ................................. 5 B. Political Participation and Mobilization ..................................... 9 C. Development of Voice and Agency ............................................ 12 III. BARRIERS TO WOMEN’S ACCESS TO ICTS ............................................. 14 IV. THE SPECIAL PROBLEM OF CYBERVIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN & GIRLS ........................................................................................................... 16 A. Terminology and Definitions ..................................................... 17 B. The Extent of Cyberviolence ...................................................... 20 C. Addressing the Ongoing Threat of CyberVAWG ....................... 21 D. Other Approaches: Forms of Informal Justice .......................... 25 E. Possible Backlash ...................................................................... 27 F. Countering Violence against Women by Using ICTs ................ 29 V. INTERNET ACCESS AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS ........... 32 A. Internet Access -

Gender, Information Technology, and Developing Countries: an Analytic Study

Gender, Information Technology, and Developing Countries: An Analytic Study By Nancy Hafkin and Nancy Taggart Academy for Educational Development (AED) For the Office of Women in Development Bureau for Global Programs, Field Support and Research United States Agency for International Development June 2001 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document has been produced under AED's Global Communications and Learning Systems (LearnLink) Project of the Human Capacity Development Center in USAID's Global Bureau, a five-year, Indefinite Quantities Contract No. HNE-1-00-96-00018-00, and Task Order 2432-21. AED acknowledges and thanks USAID's Office of Women in Development for their sponsorship and this opportunity to prepare an analytical study of the gender implications in the spread of information technology. Also, AED expresses its appreciation to Cisco Systems and the Cisco Learning Institute for their support of AED's research on women in technology training. AED gathered much of the data on information technology education and training included in this paper as part of a project funded by the Cisco Learning Institute entitled Support for Gender Strategies in the Cisco Networking Academy Program, Contract No. 12-2789. The following persons are recognized for their contribution of photographs for the paper: · Sergio Aranda (photo on page 48) · Sonia Arias (photo on page 63) · Sabina Béhague (photo on page 71) · CATT-PILOTE staff (photo on the cover and page 88) · Mary Fontaine (photos on the inside cover and pages 18, 35, and 53) · Nancy Hafkin (photo on page 73) · Linda Leonard (photo on page 97) · LTNet staff (photos on page 12 and 67) · Glenn Strachan (photo on page 43) · Photographer, unknown (photo on page 83) · Frederick Wamala (photo on page 23) Finally, thanks go to the team of LearnLink staff and readers that worked diligently to finalize production copy. -

Engendering Technology Empowering Women Pascall, A.N

Tilburg University Engendering technology empowering women Pascall, A.N. Publication date: 2012 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Pascall, A. N. (2012). Engendering technology empowering women. TiCC.Ph.D. Series 23. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. sep. 2021 ENGENDERING TECHNOLOGY EMPOWERING WOMEN PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op maandag 19 november 2012 om 14.15 uur door Athanacia Nancy Pascall geboren in Griekenland Promotores: Prof. dr. H. J. van den Herik Prof. dr. M. Diocaretz Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. dr. -

Work on Statistics and Indicators of Global Gender Inclusion Since 1980S

Nancy J. Hafkin Phone: +1 508 872-1004 (Mobile) +1 508 395-7603 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.wisat.org 135 Stonybrook Road Named in 2012 to the inaugural Framingham MA 01702 group of inductees of the Internet USA Society Hall of Fame in the category Global Connector. Summary of Decades of experience in information technology, gender and development qualifications issues, including 25 years at the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Pioneering work on statistics and indicators of gender inclusion. Awards International Telecommunication Union & UN-Women, Global Achiever Award, 2015 Women in Computing Galley, National Museum of Computing, Bletchley Park, UK, 2013+ Member, Internet Hall of Fame (first inductee group), 2012 Association for Progressive Communications, Nancy J. Hafkin Prize to encourage and recognize innovative African initiatives in information and communication technologies, 2000+ Education Ph.D. Boston University, History (certificate: African Studies) M.A. Boston University, History (concentration: Africa) B.A. Brandeis University, History Professional experience 2005-present. Senior Associate, WISAT. WISAT is a non-profit entity that promotes innovation, science and technology strategies to enable women, especially those living in developing countries, to actively participate in technology and innovation for development. Women should be able to benefit from the advantages of technological development equally with men, including access to and use of technologies and full participation in innovation systems. As a senior associate, I direct the program activities on information technology for development and have taken a lead in the group’s work on gender statistics and indicators. 2000-present. Director, Knowledge Working. Consultancy specializing in information technology, gender and international development. -

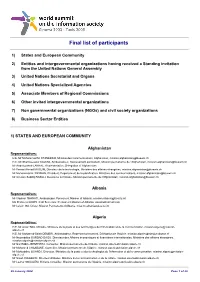

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

Africa Internet History: Highlights

AFRICA INTERNET HISTORY: HIGHLIGHTS Internet Society Galerie Jean-Malbuisson, 15 Tel: +41 22 807 1444 1775 Wiehle Ave. Tel: +1 703 439 2120 InternetSociety.org CH-1204 Geneva Fax: +41 22 807 1445 Suite 201 Fax: +1 703 326 9881 [email protected] Switzerland Reston, VA 20190, USA Contents Section 1: Organizations Section 2: Technologies Section 3: Impact Section 4: African institutions and Internet governance Section 5: Some pioneers Internet Society Galerie Jean-Malbuisson, 15 Tel: +41 22 807 1444 1775 Wiehle Ave. Tel: +1 703 439 2120 InternetSociety.org CH-1204 Geneva Fax: +41 22 807 1445 Suite 201 Fax: +1 703 326 9881 [email protected] Switzerland Reston, VA 20190, USA Introduction This document on the Africa Internet history’s highlights is a collection of information from various sources. It is not a historical document per country but rather a set of global information on the Internet mainly from 1990 to 2001 in Africa Internet Society Galerie Jean-Malbuisson, 15 Tel: +41 22 807 1444 1775 Wiehle Ave. Tel: +1 703 439 2120 InternetSociety.org CH-1204 Geneva Fax: +41 22 807 1445 Suite 201 Fax: +1 703 326 9881 [email protected] Switzerland Reston, VA 20190, USA I Organizations/Initiatives Many international organizations have played an important role in Africa Internet history. Their actions were significant in the area of infrastructure, policy, capacity building and more. This section is trying to summarize some of these actions by international organizations and research centers. Internet Society Galerie Jean-Malbuisson, 15 Tel: +41 22 807 1444 1775 Wiehle Ave. Tel: +1 703 439 2120 InternetSociety.org CH-1204 Geneva Fax: +41 22 807 1445 Suite 201 Fax: +1 703 326 9881 [email protected] Switzerland Reston, VA 20190, USA − Africa Union The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) is a programme of the African Union (AU) adopted in Lusaka, Zambia in 2001. -

Digital Activism Decoded the New Mechanics of Change

Digital Activism Decoded The New Mechanics of Change Digital Activism Decoded The New Mechanics of Change Mary Joyce, editor international debate education association New York & Amsterdam Published by: International Debate Education Association 400 West 59th Street New York, NY 10019 Copyright © 2010 by International Debate Education Association This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/deed.en_US Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Digital activism decoded : the new mechanics of change / Mary Joyce, editor. p. cm. ISBN 978-1-932716-60-3 1. Information technology--Political aspects. 2. Internet--Political aspects. 3. Cyberspace--Political aspects. 4. Social movements. 5. Protest movements. I. Joyce, Mary (Mary C.) HM851.D515 2010 303.48’40285--dc22 2010012414 Design by Kathleen Hayes Printed in the USA Contents Preface: The Problem with Digital Activism ................... vii Introduction: How to Think About Digital Activism Mary Joyce ............................................ 1 Part 1: Contexts: The Digital Activism Environment ............... 15 Infrastructure: Its Transformations and Efect on Digital Activism Trebor Scholz .......................................... 17 Applications: Picking the Right One in a Transient World Dan Schultz and Andreas Jungherr.......................... 33 Devices: The Power of Mobile Phones Brannon Cullum ........................................ 47 Economic and Social Factors: The Digital (Activism) Divide Katharine