Who Says Arizona Ain't Green?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dark Sky Sanctuaries in Arizona

Dark Sky Sanctuaries in Arizona Eric Menasco NPS Terry Reiners Arizona is the astrotourism capital of the United States. Its diverse landscape—from the Grand Canyon and ponderosa forests in the north to the Sonoran Desert and “sky islands” in the south—is home to more certified Dark Sky Places than any other U.S. state. In fact, no country outside the U.S. can rival Arizona’s 16 dark-sky communities and parks. Arizona helped birth the dark-sky preservation movement when, in 2001, the International Dark Sky Association (IDA) designated Flagstaff as the world’s very first Dark Sky Place for the city’s commitment to protecting its stargazing- friendly night skies. Since then, six other Arizona communities—Sedona, Big Park, Camp Verde, Thunder Mountain Pootseev Nightsky and Fountain Hills—have earned Dark Sky status from the IDA. Arizona also boasts nine Dark Sky Parks, defined by the IDA as lands with “exceptional quality of starry nights and a nocturnal environment that is specifically protected for its scientific, natural, educational, cultural heritage, and/or public enjoyment.” The most famous of these is Grand Canyon National Park, where remarkably beautiful night skies lend draw-dropping credence to the Park Service’s reminder that “half the park is after dark Of the 16 Certified IDA International Dark Sky Communities in the US, 6 are in Arizona. These include: • Big Park/Village of Oak Creek, Arizona • Camp Verde, Arizona • Flagstaff, Arizona • Fountain Hills, Arizona • Sedona, Arizona • Thunder Mountain Pootsee Nightsky- Kaibab Paiute Reservation, Arizona Arizona Office of Tourism—Dark Skies Page 1 Facebook: @arizonatravel Instagram: @visit_arizona Twitter: @ArizonaTourism #VisitArizona Arizona is also home to 10 Certified IDA Dark Sky Parks, including: Northern Arizona: Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument Offering multiple hiking trails around this former volcanic cinder cone, visitors can join rangers on tours to learn about geology, wildlife, and lava flows. -

Arizona, Road Trips Are As Much About the Journey As They Are the Destination

Travel options that enable social distancing are more popular than ever. We’ve designated 2021 as the Year of the Road Trip so those who are ready to travel can start planning. In Arizona, road trips are as much about the journey as they are the destination. No matter where you go, you’re sure to spy sprawling expanses of nature and stunning panoramic views. We’re looking forward to sharing great itineraries that cover the whole state. From small-town streets to the unique landscapes of our parks, these road trips are designed with Grand Canyon National Park socially-distanced fun in mind. For visitor guidance due to COVID19 such as mask-wearing, a list of tourism-related re- openings or closures, and a link to public health guidelines, click here: https://www.visitarizona. com/covid-19/. Some attractions are open year-round and some are open seasonally or move to seasonal hours. To ensure the places you want to see are open on your travel dates, please check their website for hours of operation. Prickly Pear Cactus ARIZONA RESOURCES We provide complete travel information about destinations in Arizona. We offer our official state traveler’s guide, maps, images, familiarization trip assistance, itinerary suggestions and planning assistance along with lists of tour guides plus connections to ARIZONA lodging properties and other information at traveltrade.visitarizona.com Horseshoe Bend ARIZONA OFFICE OF TOURISM 100 N. 7th Ave., Suite 400, Phoenix, AZ 85007 | www.visitarizona.com Jessica Mitchell, Senior Travel Industry Marketing Manager | T: 602-364-4157 | E: [email protected] TRANSPORTATION From east to west both Interstate 40 and Interstate 10 cross the state. -

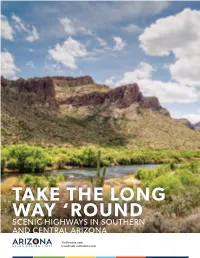

Take the Long Way 'Round

TAKE THE LONG WAY ‘ROUND SCENIC HIGHWAYS IN SOUTHERN AND CENTRAL ARIZONA VisitArizona.com traveltrade.visitarizona.com Take a road trip without the crowded interstate. It may take a little longer to get to the destination, but there is a lot more beauty and joy in the journey when you travel the scenic highways and byways that wind through hills and valleys or along the banks of rivers and lakes. Experience that moment when the long stretch of road turns to reveal magnificent vistas and natural wonders. Drive through Arizona’s varying climates and landscapes, from vast deserts to thick pine forests. This itinerary will take you to Saguaro National Park, Sabino Canyon, Mt. Lemmon, Oracle State Park, Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, Mogollon Rim, Tonto National Forest, and the Apache Trail. Hit the road for some of the most beautiful sights you will ever behold, and remember: it is worth it to take the long way ‘round. TAKE THE LONG WAY ‘ROUND ROAD MAP DAY 1 PHOENIX – TUCSON MORNING Depart the Phoenix Metropolitan Area via AZ-87 South through Chandler. The drive to Coolidge is 55.6 miles or 89.5 kilometers. As you get closer to the edge of town, you will start to pass agricultural fields and finally be released from the city into the open desert. **At Hunt Highway, AZ-87 becomes the AZ-587 if you go straight. You need to turn left onto Hunt Hwy and immediately right to continue on AZ-87 South. Stop at the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument for a selfguided tour. -

Spring 2000 Final

National Trails Day is June 3. Join us on the Arizona Trail Vol. 6, No. 1 News and Information on the State’s border-to-border Arizona Trail project Spring-2000 National Trails Day 2000 Celebrate the Arizona Trail - Millennium Legacy Trail Designation! Saturday, June 3rd is National Trails Day. All Arizona Trail select from a variety of other trail fiestas to be held in Pine, enthusiasts are encouraged to participate in this celebration of Superior, Oracle, Tucson, Patagonia, and Sierra Vista. Check the the trail! ATA has scheduled a variety of activities for you to website or call ATA for details (602-252-4794). choose from. Hike or ride the trail and/or attend one These events are a wonderful opportunity to focus of the community celebrations. a tremendous amount of attention on the success of Register with ATA and hike or ride a section of the the Arizona Trail - in local communities, statewide, Arizona Trail individually or as a group, on or before and nationally. Communities along the trail will be June 3rd. In exchange for a trail condition report reminded of this exciting volunteer and partnership- returned to ATA, you will receive a bandanna and based project going through their backyard. water bottle for your participation. Check the ATA Awareness of the trail can result in a broader base of website (www.aztrail.org) or contact the registration support to accomplish our goal of completing this coordinator, Terry Sario ([email protected] or 602- 790-mile border-to-border trail. 246-4508). ATA invites everyone to participate not only in Following your hike or ride, join other trails using the trail, but celebrating it as well at one of the enthusiasts at one of seven community events along community events on June 3rd. -

Downloaded and Reviewed on the State Parks’ Webpage Or Those Interested Could Request a Hard Copy

Governor of Arizona Janet Napolitano Arizona State Parks Board William Cordasco, Chair ting 50 ting 50 ra Y Arlan Colton ra Y b e b e a William C. Porter a le le r r e e s s William C. Scalzo C C Tracey Westerhausen Mark Winkleman 1957 - 2007 Reese Woodling 1957 - 2007 Elizabeth Stewart (2006) Arizona Outdoor Recreation Coordinating Commission Jeffrey Bell, Chair Mary Ellen Bittorf Garry Hays Rafael Payan William Schwind Duane Shroufe Kenneth E. Travous This publication was prepared under the authority of the Arizona State Parks Board. Prepared by the Statewide Planning Unit Resources Management Section Arizona State Parks 1300 West Washington Street Phoenix, Arizona 85007 (602) 542-4174 Fax: (602) 542-4180 www.azstateparks.com The preparation of this report was under the guidance from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, under the provisions of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 (Public Law 88-578, as amended). The Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin, age or disability. For additional information or to file a discrimination complaint, contact Director, Office of Equal Opportunity, Department of the Interior, Washington D.C. 20240. September 2007 ARIZONA 2008 SCORP ARIZONA 2008 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) Arizona State Parks September 2007 iii ARIZONA 2008 SCORP ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The 2008 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) for Arizona was prepared by the Planning Unit, Resources Management -

Arizona State Trust Lands Conservation Profile: State Trust Lands and State Parks

Arizona State Trust Lands Conservation Profile: State Trust Lands and State Parks STATE PARKS – Our BeST REASON FOR CONSERVATION Arizona is blessed with a diverse and well loved park Sonoran Institute, system of 30 parks throughout the state. Five parks in five counties have state trust land adjacent to their in collaboration with boundaries and have consistently been nominated conservation groups for conservation. The state trust land areas share across Arizona and with similar virtues; a pristine environment and a need for additional land to ensure their longevity for future funding from the Nina generations. Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust, has assembled Located in Mohave, Navajo, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz counties respectively, the state parks with adjacent state trust lands suitable trust land in need of conservation are: Lake Havasu, for conservation into a Homolovi Ruins, Catalina, Oracle, and Patagonia Lake. single database. The resulting profiles focus on conservation values. Political values are left for another day. Shaping the Future of the West www.sonoraninstitute.org REASON FOR CONSERVATION State Parks on State Trust Land Although these state trust lands have similar merits for conservation worthiness, the distinct Catalina and Oracle State Parks characteristics of each state park provide additional impetus for preserving the state trust Oracle State Park land adjacent to their respective boundaries. Located in Mohave County adjacent to Lake ORACLE Havasu State Park is an area dubbed Black 77 State Trust Land Rock Cove. It is known for its ease of access, for Conservation National Forest beautiful beaches, nature trails, boat ramps, 79 and convenient campsites; this spot is truly a State Trust Land ORACLE JUNCTION water sport haven. -

Oracle State Park Center for Environmental Education

Oracle State Park Center for Environmental Education International Dark Sky Park (Silver Tier) 2017 Annual Report Prepared by the Oracle Dark Skies Committee (ODSC) 2017 Annual Report to the International Dark-Sky Association Revision 1.0 27 September 2017 Page 1 of 49 Table of Contents 1. LETTER OF SUBMITTAL .................................................................................................................. 4 2. GENERAL .............................................................................................................................................. 5 2.1 BRIEF HISTORY OF ORACLE STATE PARK CENTER FOR ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION ...................... 5 2.2 NEW PARK MANAGER, INCREASED STAFF, EXPANDED OPERATIONS ..................................................... 7 2.3 IDA CONTACTS ................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.4 TIER STATUS UPGRADE PLANS ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.5 PARK VISITORS DURING PAST YEAR .............................................................................................................. 7 2.6 GOLD MEDAL AWARD PARK SYSTEM ............................................................................................................ 7 3. PARK LIGHTING ................................................................................................................................. 8 3.1 -

MINUTES of the ARIZONA STATE PARKS BOARD of ARIZONA STATE PARKS and TRAILS SEPTEMBER 19, 2019

Doug Ducey Bob Broscheid Governor Executive Director MINUTES of THE ARIZONA STATE PARKS BOARD of ARIZONA STATE PARKS AND TRAILS SEPTEMBER 19, 2019 A. CALL TO ORDER Dale Larsen, Chair of the Arizona State Parks Board called the meeting to order at 10:01AM. B. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE John Sefton, Vice Chair of the Arizona State Parks Board led the Board in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. C. BOARD MEMBERS ROLL CALL AND MISSION STATEMENT Members Present: Dale Larsen, John Sefton, Shawn Orme (Arrived at 10:05AM), Lisa Atkins (Phone), Terri Palmberg (Phone) Staff Present: Bob Broscheid, Tim Franquist, Kevin Brock, Michelle Thompson, Mickey Rogers, Matt Eberhart, Dan Roddy, Dawn Collins, Jeff Schmidt. D. AGENDA ITEMS 1. Approval of Minutes – Board may approve the Board minutes from June 28, 2019. John Sefton moved to approve the Board minutes from June 28, 2019. Lisa Atkins seconded the motion. Dale Larsen approved. John Sefton approved. Lisa Atkins approved. Terri Palmberg approved. The motion passed unanimously. 2. Fiscal Year 2020 Budget. Kevin Brock, Chief Financial Officer, presented FY 2020 operating, donations, and capital budgets. John Sefton moved to endorse the executive directors recommended FY 2020 operating, donations, and capital budgets as lump sum and that the Executive Director be authorized to implement the program as has been presented to the Governor’s Office and Legislature. Shawn Orme seconded the motion. Dale Larsen approved. John Sefton approved. Lisa Atkins abstained. Sean Orme approved. Terri Palmberg approved. The motion passed. 3. Kartchner Caverns 20th Anniversary Celebration. Michelle Thompson, Chief of Communications, briefed board members on upcoming events and activities for the 20th anniversary celebration for Kartchner Caverns State Park. -

Valid Through November 15, 2020

Valid Through November 15, 2020 Add some extra excitement to your trip with Visit Tucson’s Events Calendar. Where amazing happens all year long. Go to VisitTucson.org/Events WIN! A LUXURIOUS RESORT Win! EXPERIENCE FOR TWO Enter to win a Uniquely Southwest vacation experience for two at the Add some extra excitement to your trip iconic El Conquistador Tucson, A Hilton Resort located in the premiere with Visit Tucson’s Events Calendar. community of Oro Valley. Where amazing happens all year long. Lush desert environment, innovative cuisine and amazing views of Pusch Ridge welcome you to this award-winning resort. Your getaway Go to VisitTucson.org/Events includes two nights in a beautifully appointed suite, buffet breakfast for two, plus dinner for two on one night at our inspired Epazote Kitchen & Cocktails restaurant. Additionally, you each receive a 50-minute massage in our luxury resort spa. To win, fill out the form on the next page, drop off at the Tucson Visitor Center, 811 N. Euclid Ave., or return by mail to: SAAA, 140 N. Stone Ave., Tucson, AZ 85701. More information call SAAA at 520-499-2662. Room subject to availability and subject to change. Blackout dates may apply. cut or tear out page here cut or tear Contact property for details at 520.544.1116 or visit hiltonelconquistador.com to learn more.. All entries must be received by September 1, 2020 to be eligible to win. Drawing held September 16, 2020. ENTER TO Win! NAME ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE COUNTRY PHONE E-MAIL PURCHASE LOCATION Please add me to your email list. -

Oracle State Park Center for Environmental Education

Oracle State Park Center for Environmental Education International Dark Sky Park (Silver Tier) Nomination Package Prepared by the Oracle Dark Skies Committee (ODSC) Proposal to the International Dark-Sky Association Revision 1.0 18 July 2014 Page 1 of 128 Table of Contents 1. LETTER OF NOMINATION ...............................................................................................................5 2. LETTERS OF SUPPORT .....................................................................................................................6 3. ORACLE STATE PARK HISTORY AND INFORMATION ......................................................... 27 3.1 HISTORY OF ORACLE STATE PARK - CENTER FOR ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION.............................27 3.2 PARK INFORMATION.......................................................................................................................................30 3.3. ORACLE STATE PARK ENVIRONMENTAL/CULTURAL EDUCATION EVENTS .......................................33 4. ORACLE STATE PARK DARK SKY EVENT LOCATIONS......................................................... 36 4.1 ORACLE STATE PARK MAPS..........................................................................................................................36 4.2 DAY SKY PANORAMA PHOTOGRAPHS..........................................................................................................39 5. ORACLE STATE PARK NIGHT SKY QUALITY........................................................................... 41 5.1 CONTOUR MAPS...............................................................................................................................................41 -

1 Arizona State Parks Board South

ARIZONA STATE PARKS BOARD SOUTH MOUNTAIN PARK ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION CENTER 10409 S. CENTRAL AVENUE, PHOENIX, AZ SEPTEMBER 18, 2003 MINUTES Board Members present: Suzanne Pfister, Chairman John Hays Elizabeth Stewart William Porter William Cordasco Mark Winkleman Board Members absent: Gabriel Gonzales-Beechum Staff present: Kenneth E. Travous, Executive Director Jay Ream, Assistant Director, Parks Mark Siegwarth, Assistant Director, Administrative Services Jay Ziemann, Assistant Director, Partnerships and External Affairs Debi Busser, Executive Secretary Jean Emery, Chief of Resources Management Janet Hawks, Chief of Operations Sue Hilderbrand, Acting Chief of Grants Attorney General's Representative: Joy Hernbrode, Assistant Attorney General Patricia Boland, Assistant Attorney General A. CALL TO ORDER - ROLL CALL Chairman Pfister called the meeting to order at 9:10 a.m. Roll Call of Board Members indicated a quorum was present. B. INTRODUCTION OF BOARD MEMBERS AND AGENCY STAFF Chairman Pfister requested that the Arizona State Parks Board members and staff introduce themselves and invited any members of the public present who wished to do so as well. C. PUBLIC COMMENT Chairman Pfister noted that the Board can take Public Comment at any time during the meeting. She suggested that those who wished to address grant applications may wish to speak during that portion of the meeting. She noted that a representative from the City of Phoenix Parks and Recreation wished to speak at this time. Ms. Sarah Hall, City of Phoenix Parks and Recreation, welcomed the Board to the South Mountain Park Environmental Education Center. She noted that there is a trail that begins in the courtyard that was funded through an Arizona State Parks (ASP) Heritage Trails grant for $65,000. -

Round Roadmap Day 1 Phoenix-Tucson

TAKE THE LONG WAY ‘ROUND Scenic Drives in Southern and Central Arizona Take a road trip without the crowded interstate. It may take a little longer to get to the destination, but there is a lot more beauty and joy in the journey when you travel the scenic highways and byways that wind through hills and valleys or along the banks of rivers and lakes. This itinerary will take you to National Parks, State Parks, and National Forests. Hit the road for some of the most beautiful sights you will ever behold, and remember: it is worth it to take the long way ‘round. ROADMAP Choose your favorite set of wheels and hit the highway while we show you the path of least resistance to rediscover Arizona from vast deserts to thick pine forests. You will see all of Arizona’s varying climates and landscapes. John Weatherby DAY 1 PHOENIX-TUCSON Mark Skalny Depart the Phoenix Metropolitan Area via AZ-87 south through Chandler. The drive to Coolidge is 65 miles or 104.6 km. As you get closer to the edge of town, you will start to pass agricultural fields and finally be released from the city into the open desert. At Hunt Highway, avoid continuing straight onto AZ-587. Instead turn left onto Hunt Hwy and immediately turn right to continue on AZ-87 South. Potential stop at the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument for a self- guided tour. Visit the NPS website for up to date visitation availability. Tel: (520) 723-3172 • 1100 W. Ruins Dr, Coolidge, AZ 85128 NPS Drive east on AZ-287 to AZ-79 south and then go right on to AZ-77 to Oro Valley.