Papa Bear's Season

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerry Kramer

SCOUTING REPORT JERRY KRAMER Updated: March 19, 2016 Contents Overall Analysis __________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Game Reviews ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 REVISION LISTING DATE DESCRIPTION February 10, 2015 Initial Release March 19, 2016 Added the following games: 10/19/58, 11/15/59, and 1/15/67 OVERALL ANALYSIS Overall Analysis POSITION Right Guard HEIGHT AND WEIGHT Height: 6’3” Weight: 245 TEAMS 1958-68 Green Bay Packers UNIFORM NUMBER 64 SCOUTS Primary Scout: Ken Crippen Secondary Scout: Matt Reaser Page 1 http://www.kencrippen.com OVERALL ANALYSIS STRENGTHS • Excellent quickness and agility • Run blocking is exceptional • Can pull effectively and seal the blocks WEAKNESSES • Can get off-balance on pass blocking • Occasionally pushed back on a bull rush • Has a habit of not playing snap-to-whistle on pass plays BOTTOM LINE Kramer is excellent at run blocking, but not as good on pass blocking. Whether he is run blocking or pass blocking, he shows good hand placement. He missed many games in 1961 and 1964 due to injury. Also kicked field goals and extra points for the team in 1962-63 and 1968. He led the league in field goal percentage in 1962. Run Blocking: When pulling, he is quick to get into position and gains proper leverage against the defender. While staying on the line to run block, he shows excellent explosion into the defender and can turn the defender away from the runner. Pass Blocking: He can get pushed a little far into the backfield and lose his balance. He also has a habit of not playing snap-to-whistle. -

Open for Service :: ::: "Fantastic!" "Beautiful!" "Just Great!" These Were Some Ri of the Superlatives Used by Ft

FORT LEONARD WOOD ID( Volume 5 Numlper 9 August 28, 1970 12 Paves Walker Service Club Open for Service :: ::: "Fantastic!" "Beautiful!" "Just great!" These were some ri of the superlatives used by Ft. Leonard Wood personnel when asked their opinion of the new Walker Service Club, which opened :!.K : s. Sunday, Aug. 23. ' ' ' .. The new club is named in honor of the late Major General George H. Walker, a former commanding general of Ft. Wood. Special guests at the opening eremonies included Mrs. George H. Walker, her son, George H. Walker III, and her daughter, Mrs. Tom O'Connor. Also pre- sent were Major General W. T. Ft. Belvoir, Va. He served >i: Bradley, post commanding gen- as commanding general, United eral, Mrs. Bradley, Major Gen- States Army Training Center eral Carroll Dunn, acting chief of Engineer and Ft. Leonard Wood engineers; Mrs. Dunn, Brigadier from September 1967 to October General Carleton C. Preer Jr., 1968. deputy commanding general, and Walker Service Club was Mrs. Preer. opened to all post personnel at 1 p. m. Sunday. During the day, Following a 30-minute outdoor more than 2,000 soldiers and concert by the 399th Army Band, their guests visited the new MG Dunn presented the key to facility. The afternoon's rnain MRS. GEORGE H. WALKER and MGW. T. Bradley, at the new Walker Service Club. (PIO Photo by the new building to MG Bradley. post commanding general, cut the ceremonial ribbon PFC David L. Teer) The presentation of the key sym- attraction was the appearance of The Golddiggers, the unique '* * * * bolized the transfer of control of the building from the Corps all-girl singing group. -

2018 DETROIT LIONS SCHEDULE PRESEASON GAME 1: at OAKLAND RAIDERS PRESEASON Date

2018 DETROIT LIONS SCHEDULE PRESEASON GAME 1: AT OAKLAND RAIDERS PRESEASON Date: ...............................................................................Friday, August 10 DATE OPPONENT TV TIME/RESULT Kickoff: ................................................................................ 10:30 p.m. ET 8/10 at Oakland Raiders WJBK-TV FOX 2 10:30 p.m. Stadium: ....................................Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum 8/17 NEW YORK GIANTS WJBK-TV FOX 2 7:00 p.m. Capacity: .........................................................................................63,200 8/24 at Tampa Bay Buccaneers CBS# 8:00 p.m. Playing Surface: ..............................................................................Grass 8/30 CLEVELAND BROWNS WJBK-TV FOX 2 7:00 p.m. 2017 Records: .................................................Lions 9-7; Raiders 6-10 TELEVISION REGULAR SEASON Network: ............................................................................ WJBK-TV FOX 2 DATE OPPONENT TV TIME/RESULT Play-By-Play: .....................................................................Matt Shepard 9/10 NEW YORK JETS ESPN# 7:10 p.m. Color: ..................................................................................Chris Spielman 9/16 at San Francisco 49ers FOX 4:05 p.m. Sideline: ...................................................................................... Tori Petry 9/23 NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS NBC# 8:20 p.m. LIONS RADIO NETWORK 9/30 at Dallas Cowboys FOX 1:00 p.m. Flagship: ............................................................................... -

2010 FBS HOF Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NFF ANNOUNCES 2010 FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION COLLEGE FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME CLASS 12 PLAYERS AND TWO COACHES TO ENTER COLLEGE FOOTBALL’S ULTIMATE SHRINE NEW YORK, May 27, 2010 – From the national ballot of 77 candidates and a pool of hundreds of eligible nominees, Archie Manning, chairman of The National Football Foundation & College Hall of Fame, announced the 2010 College Football Hall of Fame Football Bowl Subdivision Class, which includes the names of 12 First Team All-America players and two legendary coaches. 2010 COLLEGE FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME CLASS PLAYERS • DENNIS BYRD – DT, North Carolina State (1964-67) • RONNIE CAVENESS – C, Arkansas (1962-64) • RAY CHILDRESS – DL, Texas A&M (1981-84) • RANDY CROSS – OG, UCLA (1973-75) • SAM CUNNINGHAM – RB, Southern California (1970-72) • MARK HERRMANN – QB, Purdue (1977-80) • CLARKSTON HINES – WR, Duke (1986-89) • DESMOND HOWARD – WR, Michigan (1989-91) • CHET MOELLER – DB, Navy (1973-75) • JERRY STOVALL – HB, LSU (1960-62) • PAT TILLMAN* – LB, Arizona State (1994-97) • ALFRED WILLIAMS – LB, Colorado (1987-90) * Deceased COACHES • BARRY ALVAREZ – 118-73-4 (.615) – Wisconsin (1990-2005) • GENE STALLINGS** – 89-70-1 (.559) – Texas A&M (1965-71), Alabama (1990-96) ** Selection from the FBS Veterans Committee - more - “We are incredibly proud to honor this year’s class of Hall of Famers for their leadership, athleticism and success on the college gridiron,” said Manning, a 1989 College Football Hall of Famer from Ole Miss. “They are all well-deserving of this recognition, and we look forward to celebrating with them and their families in New York. -

Jan. 17, Not .13 Police Broke Into the ’ PAG Motor I Hartford, Nov

Daughtera of Uberty, No. /12S, Members of Reynolds Circle and ' The Lucy fipei.„«r Group of .lec- wlU meet tomorrow at 7:30 p.m. Ward Circle of South ■ Methodist ond Congtegatlonol Church wlU Smith Heads Juvertiles Blamed hy Police About Town at Orange Hall. Mra. Peter Oaul- Church will meet tomorrow at 8 meet 'Wednesday at 2 p.m. at-the ton of the West Hartford Lodge m. in Susannah Wesley Hall, church to sew cancer pads. Member » ( the Audit TJm llw ichw tw Nile Club wlU and her imnimlttee will preside at le Rev. and Mrs. Henry Mousley MAHRC Drive For False Alarms^ ^Bomhs^ FUNERAL HOME Bnrenn of Olrcalntton meet tomorrow at 8 p.ni. at the the installation of officers. Re- will speak dn “ Strange Lands and Manchester Assembly, Order of Mancheater— A City of Village Charm Friendly People." and will show borne of Mrt. Walter Waddell, Bol freshmenta will be served by Mra. Rainbow' Girls, will hold a business seventeen Juvenlle.__and-’a’ Joseph Johnstonl and committee. slides of their trip to the Holy meeting tonight at 7:3i0 at the Ma^ More than 13,000 lettera of ap keep A'vare of what their children FUNERAL ton Center Rd., Bolton. Land. sonic Temple. Offlciers will wear year-old boy, have been taken Into peal have been mailed to towms- custody by police In connection are doing. The evidence Is that the VOL. LXXXI, NO. 38 (FOURTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 1961 (Cloaalfled Advertiatng on Page 12) PRICE FIVR GBNTS' white. , peopl'e for the annual fund drive bombs were made in the cellars of SERVICE Sgt. -

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 7, No. 5 (1985) THE 1920s ALL-PROS IN RETROSPECT By Bob Carroll Arguments over who was the best tackle – quarterback – placekicker – water boy – will never cease. Nor should they. They're half the fun. But those that try to rank a player in the 1980s against one from the 1940s border on the absurd. Different conditions produce different results. The game is different in 1985 from that played even in 1970. Nevertheless, you'd think we could reach some kind of agreement as to the best players of a given decade. Well, you'd also think we could conquer the common cold. Conditions change quite a bit even in a ten-year span. Pro football grew up a lot in the 1920s. All things considered, it's probably safe to say the quality of play was better in 1929 than in 1920, but don't bet the mortgage. The most-widely published attempt to identify the best players of the 1920s was that chosen by the Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee in celebration of the NFL's first 50 years. They selected the following 18-man roster: E: Guy Chamberlin C: George Trafton Lavie Dilweg B: Jim Conzelman George Halas Paddy Driscoll T: Ed Healey Red Grange Wilbur Henry Joe Guyon Cal Hubbard Curly Lambeau Steve Owen Ernie Nevers G: Hunk Anderson Jim Thorpe Walt Kiesling Mike Michalske Three things about this roster are striking. First, the selectors leaned heavily on men already enshrined in the Hall of Fame. There's logic to that, of course, but the scary part is that it looks like they didn't do much original research. -

Kapp-Ing a Memorable Campaign

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol 19, No. 1 (1997) Kapp-ing A Memorable Campaign `Injun' Joe Kapp spirited the '69 Vikings to an NFL championship By Ed Gruver He was called "Injun" Joe, despite the fact his heritage was a mix of Mexican and German blood, and he quarterbacked an NFL championship team, despite owning a passing arm that produced more wounded ducks than his hunter-head coach, Bud Grant, who spent pre-dawn hours squatting with a rifle in a Minneapolis duck blind. But in 1969, a season that remains memorable in the minds of Minnesota football fans, "Injun" Joe Kapp blazed a trail through the National Football League and bonded the Vikings into a formidable league champion, a family of men whose slogan, "Forty for Sixty," was testament to their togetherness. "I liked Joe," Grant said once. "Everybody liked Joe, he's a likeable guy. In this business, you play the people who get the job done, and Joe did that." John Beasley, who played tight end on the Vikings' '69 team, called Kapp "a piece of work...big and loud and fearless." Even the Viking defense rallied behind Kapp, an occurrence not so common on NFL teams, where offensive and defensive players are sometimes at odds with another. Witness the New York Giants teams of the late 1950s and early 1960s, where middle linebacker Sam Huff would tell halfback Frank Gifford, "Hold 'em Frank, and we'll score for you." No such situation occurred on the '69 Vikings, a fact made clear by Minnesota safety Dale Hackbart. "Playing with Kapp was like playing in the sandlot," Hackbart said. -

Mcafee Takes a Handoff from Sid Luckman (1947)

by Jim Ridgeway George McAfee takes a handoff from Sid Luckman (1947). Ironton, a small city in Southern Ohio, is known throughout the state for its high school football program. Coach Bob Lutz, head coach at Ironton High School since 1972, has won more football games than any coach in Ohio high school history. Ironton High School has been a regular in the state football playoffs since the tournament’s inception in 1972, with the school winning state titles in 1979 and 1989. Long before the hiring of Bob Lutz and the outstanding title teams of 1979 and 1989, Ironton High School fielded what might have been the greatest gridiron squad in school history. This nearly-forgotten Tiger squad was coached by a man who would become an assistant coach with the Cleveland Browns, general manager of the Buffalo Bills and the second director of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The squad featured three brothers, two of which would become NFL players, in its starting eleven. One of the brothers would earn All-Ohio, All-American and All-Pro honors before his enshrinement in Canton, Ohio. This story is a tribute to the greatest player in Ironton High School football history, his family, his high school coach and the 1935 Ironton High School gridiron squad. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the undefeated and untied Ironton High School football team featuring three players with the last name of McAfee. It was Ironton High School’s first perfect football season, and the school would not see another such gridiron season until 1978. -

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER the Following Players Comprise the 1967 Season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER The following players comprise the 1967 season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. ATLANTA ATLANTA BALTIMORE BALTIMORE OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Tommy McDonald End: Sam Williams EB: Willie Richardson End: Ordell Braase Jerry Simmons TC OC Jim Norton Raymond Berry Roy Hilton Gary Barnes Bo Wood OC Ray Perkins Lou Michaels KA KOA PB Ron Smith TA TB OA Bobby Richards Jimmy Orr Bubba Smith Tackle: Errol Linden OC Bob Hughes Alex Hawkins Andy Stynchula Don Talbert OC Tackle: Karl Rubke Don Alley Tackle: Fred Miller Guard: Jim Simon Chuck Sieminski Tackle: Sam Ball Billy Ray Smith Lou Kirouac -

2012 Rebel Football Game Notes

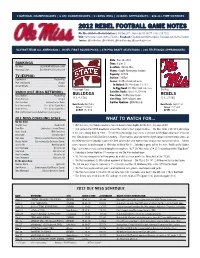

3 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS | 6 SEC CHAMPIONSHIPS | 21 BOWL WINS | 33 BOWL APPEARANCES | 626 ALL-TIME VICTORIES 22012012 RREBELEBEL FFOOTBALLOOTBALL GGAMEAME NNOTESOTES Ole Miss Athletics Media Relations | PO Box 217 | University, MS 38677 | 662-915-7522 Web: OleMissSports.com, OleMissFB.com | Facebook: Facebook.com/OleMissSports, Facebook.com/OleMissFootball Twitter: @OleMissNow, @OleMissFB, @RebelGameday, @CoachHughFreeze 54 FIRST-TEAM ALL AMERICANS | 19 NFL FIRST ROUND PICKS | 279 PRO DRAFT SELECTIONS | 216 TELEVISION APPEARANCES Date: Nov. 24, 2012 RANKINGS Time: 6 p.m. CT Ole Miss . BCS-NR/AP-NR/Coaches-NR Location: Oxford, Miss. Mississippi State . .BCS-NR/AP-t25/Coaches-24 Venue: Vaught-Hemingway Stadium Capacity: 60,580 TV (ESPNU) Surface: FieldTurf Clay Matvick . Play-by-Play Series: Ole Miss leads 60-42-6 Matt Stinchcomb . Analyst Allison Williams . Sideline In Oxford: Ole Miss leads 21-11-3 Mississippi State In Egg Bowl: Ole Miss leads 54-25-5 Ole Miss RADIO (OLE MISS NETWORK) BULLDOGS Satellite Radio: Sirius 94, XM 198 REBELS David Kellum . Play-by-Play Live Stats: OleMissSports.com Harry Harrison . Analyst (8-3, 4-3 SEC) Live Blog: OleMissSports.com (5-6, 2-5 SEC) Stan Sandroni . Sideline/Locker Room Twitter Updates: @OleMissFB Head Coach: Dan Mullen Head Coach: Hugh Freeze Brett Norsworthy . Pre- & Post-Game Host Career: 29-20/4th Career: 35-13/4th Richard Cross . Pre- & Post-Game Host At MSU: 29-20/4th At UM: 5-6/1st Web: OleMissSports.com RebelVision (subscription) OLE MISS COACHING STAFF WHAT TO WATCH FOR... On the field: Hugh Freeze . Head Coach • With five wins, the Rebels need one more to become bowl eligible for the first time since 2009. -

1952 Bowman Football (Large) Checkist

1952 Bowman Football (Large) Checkist 1 Norm Van Brocklin 2 Otto Graham 3 Doak Walker 4 Steve Owen 5 Frankie Albert 6 Laurie Niemi 7 Chuck Hunsinger 8 Ed Modzelewski 9 Joe Spencer 10 Chuck Bednarik 11 Barney Poole 12 Charley Trippi 13 Tom Fears 14 Paul Brown 15 Leon Hart 16 Frank Gifford 17 Y.A. Tittle 18 Charlie Justice 19 George Connor 20 Lynn Chandnois 21 Bill Howton 22 Kenneth Snyder 23 Gino Marchetti 24 John Karras 25 Tank Younger 26 Tommy Thompson 27 Bob Miller 28 Kyle Rote 29 Hugh McElhenny 30 Sammy Baugh 31 Jim Dooley 32 Ray Mathews 33 Fred Cone 34 Al Pollard 35 Brad Ecklund 36 John Lee Hancock 37 Elroy Hirsch 38 Keever Jankovich 39 Emlen Tunnell 40 Steve Dowden 41 Claude Hipps 42 Norm Standlee 43 Dick Todd Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Babe Parilli 45 Steve Van Buren 46 Art Donovan 47 Bill Fischer 48 George Halas 49 Jerrell Price 50 John Sandusky 51 Ray Beck 52 Jim Martin 53 Joe Bach 54 Glen Christian 55 Andy Davis 56 Tobin Rote 57 Wayne Millner 58 Zollie Toth 59 Jack Jennings 60 Bill McColl 61 Les Richter 62 Walt Michaels 63 Charley Conerly 64 Howard Hartley 65 Jerome Smith 66 James Clark 67 Dick Logan 68 Wayne Robinson 69 James Hammond 70 Gene Schroeder 71 Tex Coulter 72 John Schweder 73 Vitamin Smith 74 Joe Campanella 75 Joe Kuharich 76 Herman Clark 77 Dan Edwards 78 Bobby Layne 79 Bob Hoernschemeyer 80 Jack Carr Blount 81 John Kastan 82 Harry Minarik 83 Joe Perry 84 Ray Parker 85 Andy Robustelli 86 Dub Jones 87 Mal Cook 88 Billy Stone 89 George Taliaferro 90 Thomas Johnson Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© -

The Ice Bowl: the Cold Truth About Football's Most Unforgettable Game

SPORTS | FOOTBALL $16.95 GRUVER An insightful, bone-chilling replay of pro football’s greatest game. “ ” The Ice Bowl —Gordon Forbes, pro football editor, USA Today It was so cold... THE DAY OF THE ICE BOWL GAME WAS SO COLD, the referees’ whistles wouldn’t work; so cold, the reporters’ coffee froze in the press booth; so cold, fans built small fires in the concrete and metal stands; so cold, TV cables froze and photographers didn’t dare touch the metal of their equipment; so cold, the game was as much about survival as it was Most Unforgettable Game About Football’s The Cold Truth about skill and strategy. ON NEW YEAR’S EVE, 1967, the Dallas Cowboys and the Green Bay Packers met for a classic NFL championship game, played on a frozen field in sub-zero weather. The “Ice Bowl” challenged every skill of these two great teams. Here’s the whole story, based on dozens of interviews with people who were there—on the field and off—told by author Ed Gruver with passion, suspense, wit, and accuracy. The Ice Bowl also details the history of two legendary coaches, Tom Landry and Vince Lombardi, and the philosophies that made them the fiercest of football rivals. Here, too, are the players’ stories of endurance, drive, and strategy. Gruver puts the reader on the field in a game that ended with a play that surprised even those who executed it. Includes diagrams, photos, game and season statistics, and complete Ice Bowl play-by-play Cheers for The Ice Bowl A hundred myths and misconceptions about the Ice Bowl have been answered.