Binge-Watching: Video-On-Demand, Quality TV and Mainstreaming Fandom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Fill Your Summer with Music Draft

FILL YOUR SUMMER WITH MUSIC DRAFT SUMMER 2020 CLASSICAL | JAZZ | FOLK | POP | WORLD = THE MEMORABLE ROCKPORT MUSIC EXPERIENCES EXPERIENCE DEMAND AN INSPIRED • World-class artists EXCEPTIONAL from around the globe • stellar acoustics SPACE. • engaging and accessible community events for all ages INTIMATE • A warm, inviting setting for an unparalleled "…beautiful to the eye concert experience as well as the the ear" The New York Times • Salon-like setting evoking ©Acadia Mezzofanti ©Acadia late night cabarets, jazz clubs and Celtic sessions CONTENTS 5 SEASIDE 39th Annual • Gorgeous harbor views ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL • Picturesque New England June 12–July 12 | August 7-9 coastal village 18 Ten years ago, the opening of the Shalin Liu 9th Annual ROCKPORT JAZZ FESTIVAL Performance Center brought a much-anticipated July 26–August 2 dream to reality for Rockport Music. Originally founded as a chamber music festival in the 80’s, 21 Rockport Music’s new concert hall has truly SUMMER AT ROCKPORT surpassed all expectations. With the opening of Jazz, Folk, Pop & World the hall, the organization has seen exponential May–September growth into multiple musical genres, hosted 28 broadcast events from around the world, and is 2nd Annual ROCKPORT CELTIC FESTIVAL YEAR-ROUND considered “one of the most beautiful halls in OFFICIAL the country.” This year we celebrate the 10th August 27–30 PARTNERS EXCLUSIVE REALTOR anniversary of its opening with a spectacular 30 OFFICIAL HOTEL OFFICIAL TRANSPORTATION summer gala on June 5. We hope you'll join us! -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 1986 Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Deegan, Mary Jo, "Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek"" (1986). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 368. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/368 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THIS FILE CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING MATERIALS: Deegan, Mary Jo. 1986. “Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in ‘Star Trek.’” Pp. 209-224 in Eros in the Mind’s Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film, edited by Donald Palumbo. (Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, No. 21). New York: Greenwood Press. 17 Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in IIStar Trek" MARY JO DEEGAN Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise, its five year mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before. These words, spoken at the beginning of each televised "Star Trek" episode, set the stage for the fan tastic future. -

Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television

temp Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television ANGELO RESTIVO Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television A production of the Console- ing Passions book series Edited by Lynn Spigel Breaking Bad and Cinematic Television ANGELO RESTIVO DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Warnock and News Gothic by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Restivo, Angelo, [date] author. Title: Breaking bad and cinematic television / Angelo Restivo. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: Spin offs : a production of the Console-ing Passions book series | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018033898 (print) LCCN 2018043471 (ebook) ISBN 9781478003441 (ebook) ISBN 9781478001935 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 9781478003083 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Breaking bad (Television program : 2008–2013) | Television series— Social aspects—United States. | Television series—United States—History and criticism. | Popular culture—United States—History—21st century. Classification: LCC PN1992.77.B74 (ebook) | LCC PN1992.77.B74 R47 2019 (print) | DDC 791.45/72—dc23 LC record available at https: // lccn.loc.gov/2018033898 Cover art: Breaking Bad, episode 103 (2008). Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Georgia State University’s College of the Arts, School of Film, Media, and Theatre, and Creative Media Industries Institute, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. Not to mention that most terrible drug—ourselves— which we take in solitude. —WALTER BENJAMIN Contents note to the reader ix acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 The Cinematic 25 2 The House 54 3 The Puzzle 81 4 Just Gaming 116 5 Immanence: A Life 137 notes 159 bibliography 171 index 179 Note to the Reader While this is an academic study, I have tried to write the book in such a way that it will be accessible to the generally educated reader. -

ORANGE IS the NEW BLACK PILOT Written By: Jenji Kohan

ORANGE IS THE NEW BLACK PILOT Written by: Jenji Kohan Based on the Memoir by Piper Kerman Writer's first 5/22/12 BATHING MONTAGE: We cycle through a series of scenes with voice overs. Underneath the dialogue, one song plays throughout. Perhaps it’s ‘Tell Me Something Good,’ by Rufus and Chaka Khan or something better or cheaper or both that the music supervisor finds for us. INT. CONNECTICUT KITCHEN - DAY - 1979 A beautiful, fat, blonde baby burbles and splashes in a kitchen sink. A maternal hand pulls out the sprayer and gently showers the baby who squeals with joy. PIPER (V.O.) I’ve always loved getting clean. CUT TO: INT. TRADITIONAL BATHROOM - 1984 Five year old Piper plays in a bathtub surrounded by toys. PIPER (V.O.) Water is my friend. CUT TO: INT. GIRLY BATHROOM - 1989 Ten year old Piper lathers up and sings her heart out into a shampoo bottle. PIPER (V.O.) I love baths. I love showers. CUT TO: INT. DORM BATHROOM - 1997 Seventeen year old Piper showers with a cute guy. PIPER (V.O.) I love the smell of soaps and salts. CUT TO: INT. LOFT BATHROOM - 1999 Twenty year old Piper showers with a woman. (ALEX) ORANGE IS THE NEW BLACK "Pilot" JENJI DRAFT 2. PIPER (V.O.) I love to lather. CUT TO: INT. DAY SPA - 2004 Piper sits in a jacuzzi with girlfriends. PIPER (V.O.) I love to soak. CUT TO: INT. APARTMENT - 2010 Piper in a clawfoot tub in a brownstone in Brooklyn with LARRY. PIPER (V.O.) It’s my happy place. -

Grand Haunting

The Independent Voice of Salt Lake Community College FREE Wednesday october 31, 2012 THE Issue 12/ fall '12 GLOBEVisit us online at globeslcc.com Inside: your Globe Halloween hookup - Masks for the Lazy pg. 5 GRAND Visit HAUNTING www. Photo by Trisha Gold globeslcc.com South City theatre a Unexplained events have been known to happen at the Grand Theatre. major controversy when the high anything,” said Rufendr. “There for daily news hotspot for ghostly school closed in 1988, and many are some seats that people won’t sit alumni were heartbroken by the in. When we asked them why, they updates shenanigans decision. have no answer for it. They just In 1992, SLCC finishedwon’t sit there.” Kachina Choate began about five or six years converting the building into the Theater productions create a Staff Reporter ago. Most of the occurrences are college’s new South City Campus lot of energy, and according to reported to have happened in the after years of renovation. paranormal professionals there The “break a leg” phrase is widely theatre’s house. There have been “There are always stories of the are many reasons why places have known as a safe way to wish luck to no backstage sightings, but actors old students who have come back ghosts. an actor, and theatre professionals have reported odd things happing, from the former South High,” “Maybe [the ghost] had some and patrons are commonly known such as a switch suddenly turning Rufendr. “There is a boy and a special connection to [the Grand] as a superstitious lot. -

Television Content Quality and Engagement

GONZÁLEZ, M., RONCALLO-DOW, S., ARANGO-FORERO, G. Y URIBE-JONGBLOED, E. Television content quality and engagement CUADERNOS.INFO Nº 37 ISSN 0719-3661 Versión electrónica: ISSN 0719-367x http://www.cuadernos.info doi: 10.7764/cdi.37.812 Received: 08-06-2015 / Accepted: 11-04-2015 Television content quality and engagement: Analysis of a private channel in Colombia1 Calidad en contenidos televisivos y engagement: Análisis de un canal privado en Colombia Qualidade de conteúdos televisivos e engagement: Análise de um canal privado na Colômbia MANUEL IGNACIO GONZÁLEZ BERNAL2, Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de La Sabana. Chía, Colombia [[email protected]] SERGIO RONCALLO-DOW, Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de La Sabana. Chía, Colombia [[email protected]] GERMÁN ARANGO-FORERO, Facultad de Comunicación, Universidad de La Sabana. Chía, Colombia [[email protected]] ENRIQUE URIBE-JONGBLOED, Departamento de Comunicación Social, Universidad del Norte. Barranquilla, Colombia [[email protected]] ABSTRACT RESUMEN RESUMO This paper presents the results of a Este artículo expone los resultados de Este artigo expõe os resultados de content analysis and an inquiry into un proyecto de investigación enfocado en um projeto de pesquisa enfocado em Colombian audiences regarding the comprender los elementos que intervienen compreender os elementos que intervêm concept of ‘quality television’ and its en la generación de engagement por parte na geração de engagement por parte effect upon engagement. The results de los televidentes colombianos y el aporte dos telespectadores colombianos e a show that for the sampled audience del concepto de ‘calidad televisiva’ a ese contribuição do conceito de ‘qualidade the most relevant elements in terms of proceso. -

All Ten Episodes of the Second Season of Amazon Original Series Alpha House Are Now Available on Amazon Prime Instant Video in the UK, US and Germany

All Ten Episodes of the Second Season of Amazon Original Series Alpha House Are Now Available on Amazon Prime Instant Video in the UK, US and Germany October 24, 2014 From Doonesbury creator Garry Trudeau, appearances this season include Bill Murray (Groundhog Day), Penn Jillette (Penn & Teller), Andy Cohen (Watch What Happens Live), U.S. Senators John McCain and Elizabeth Warren, Matt Lauer and Savannah Guthrie (Today Show), Rachel Maddow (The Rachel Maddow Show), Former Presidential Advisor David Axelrod, and Former Democratic Political Advisor George Stephanopoulos (Good Morning America), among many others LONDON, 24th October 2014 - Amazon today announced all 10 episodes of the second season of Garry Trudeau’s critically-acclaimed political comedy series Alpha House are now available on Prime Instant Video in the UK, US and Germany. John Goodman (Argo), Mark Consuelos (All My Children), Clark Johnson (The Wire) and Matt Malloy (Six Feet Under) reprise their roles as Republican Senators living under one roof in Washington, D.C. dealing with the outrageous—and sometimes all-too-real—foibles of Beltway life. The series is produced by Trudeau,Elliot Webb (Mob City) and NBC News contributor Jonathan Alter. Customers can binge watch both seasons of Alpha House now through Prime Instant Video on more than 400 devices, including Kindle Fire, iPad, iPhone, Xbox, PlayStation, Wii and Wii U, amongst others, and online at www.amazon.co.uk/PIV. What’s more this content is accessible both on-the-go and from the comfort of customers’ homes, through Amazon Fire Phone and Amazon Fire TV. Delivering hilarious insider insights from the master of political satire, the new season of Alpha House finds the Senators manoeuvring the hallways of Capitol Hill with a looming midterm election and an unclear political future. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

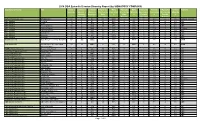

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Signatory Company Title Total # of Combined # Combined # Episodes Male # Episodes Male # Episodes Female # Episodes Female Network Episodes Women + Women + Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Minority Minority % Male % Male % Female % Female % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 50/50 Productions, LLC Workaholics 13 0 0% 13 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Comedy Central ABC Studios Betrayal 12 1 8% 11 92% 0 0% 1 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Castle 23 3 13% 20 87% 1 4% 2 9% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Criminal Minds 24 8 33% 16 67% 5 21% 2 8% 1 4% CBS ABC Studios Devious Maids 13 7 54% 6 46% 2 15% 4 31% 1 8% Lifetime ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 7 29% 17 71% 1 4% 2 8% 4 17% ABC ABC Studios Intelligence 12 4 33% 8 67% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Mixology 12 0 0% 13 108% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Revenge 22 6 27% 16 73% 0 0% 6 27% 0 0% ABC And Action LLC Tyler Perry's Love Thy Neighbor 52 52 100% 0 0% 52 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN And Action LLC Tyler Perry's The Haves and 36 36 100% 0 0% 36 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN The Have Nots BATB II Productions Inc. Beauty & the Beast 16 1 6% 15 94% 0 0% 1 6% 0 0% CW Black Box Productions, LLC Black Box, The 13 4 31% 9 69% 0 0% 4 31% 0 0% ABC Bling Productions Inc.