Kangas Et Al 2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cannabinoid Receptors and the Endocannabinoid System: Signaling and Function in the Central Nervous System

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Cannabinoid Receptors and the Endocannabinoid System: Signaling and Function in the Central Nervous System Shenglong Zou and Ujendra Kumar * Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-604-827-3660; Fax: +1-604-822-3035 Received: 9 February 2018; Accepted: 11 March 2018; Published: 13 March 2018 Abstract: The biological effects of cannabinoids, the major constituents of the ancient medicinal plant Cannabis sativa (marijuana) are mediated by two members of the G-protein coupled receptor family, cannabinoid receptors 1 (CB1R) and 2. The CB1R is the prominent subtype in the central nervous system (CNS) and has drawn great attention as a potential therapeutic avenue in several pathological conditions, including neuropsychological disorders and neurodegenerative diseases. Furthermore, cannabinoids also modulate signal transduction pathways and exert profound effects at peripheral sites. Although cannabinoids have therapeutic potential, their psychoactive effects have largely limited their use in clinical practice. In this review, we briefly summarized our knowledge of cannabinoids and the endocannabinoid system, focusing on the CB1R and the CNS, with emphasis on recent breakthroughs in the field. We aim to define several potential roles of cannabinoid receptors in the modulation of signaling pathways and in association with several pathophysiological conditions. We believe that the therapeutic significance of cannabinoids is masked by the adverse effects and here alternative strategies are discussed to take therapeutic advantage of cannabinoids. Keywords: cannabinoid; endocannabinoid; receptor; signaling; central nervous system 1. Introduction The plant Cannabis sativa, better known as marijuana, has long been used for medical purpose throughout human history. -

N-Acyl-Dopamines: Novel Synthetic CB1 Cannabinoid-Receptor Ligands

Biochem. J. (2000) 351, 817–824 (Printed in Great Britain) 817 N-acyl-dopamines: novel synthetic CB1 cannabinoid-receptor ligands and inhibitors of anandamide inactivation with cannabimimetic activity in vitro and in vivo Tiziana BISOGNO*, Dominique MELCK*, Mikhail Yu. BOBROV†, Natalia M. GRETSKAYA†, Vladimir V. BEZUGLOV†, Luciano DE PETROCELLIS‡ and Vincenzo DI MARZO*1 *Istituto per la Chimica di Molecole di Interesse Biologico, C.N.R., Via Toiano 6, 80072 Arco Felice, Napoli, Italy, †Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, R. A. S., 16/10 Miklukho-Maklaya Str., 117871 Moscow GSP7, Russia, and ‡Istituto di Cibernetica, C.N.R., Via Toiano 6, 80072 Arco Felice, Napoli, Italy We reported previously that synthetic amides of polyunsaturated selectivity for the anandamide transporter over FAAH. AA-DA fatty acids with bioactive amines can result in substances that (0.1–10 µM) did not displace D1 and D2 dopamine-receptor interact with proteins of the endogenous cannabinoid system high-affinity ligands from rat brain membranes, thus suggesting (ECS). Here we synthesized a series of N-acyl-dopamines that this compound has little affinity for these receptors. AA-DA (NADAs) and studied their effects on the anandamide membrane was more potent and efficacious than anandamide as a CB" transporter, the anandamide amidohydrolase (fatty acid amide agonist, as assessed by measuring the stimulatory effect on intra- hydrolase, FAAH) and the two cannabinoid receptor subtypes, cellular Ca#+ mobilization in undifferentiated N18TG2 neuro- CB" and CB#. NADAs competitively inhibited FAAH from blastoma cells. This effect of AA-DA was counteracted by the l µ N18TG2 cells (IC&! 19–100 M), as well as the binding of the CB" antagonist SR141716A. -

The Selective Reversible FAAH Inhibitor, SSR411298, Restores The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The selective reversible FAAH inhibitor, SSR411298, restores the development of maladaptive Received: 22 September 2017 Accepted: 26 January 2018 behaviors to acute and chronic Published: xx xx xxxx stress in rodents Guy Griebel1, Jeanne Stemmelin2, Mati Lopez-Grancha3, Valérie Fauchey3, Franck Slowinski4, Philippe Pichat5, Gihad Dargazanli4, Ahmed Abouabdellah4, Caroline Cohen6 & Olivier E. Bergis7 Enhancing endogenous cannabinoid (eCB) signaling has been considered as a potential strategy for the treatment of stress-related conditions. Fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) represents the primary degradation enzyme of the eCB anandamide (AEA), oleoylethanolamide (OEA) and palmitoylethanolamide (PEA). This study describes a potent reversible FAAH inhibitor, SSR411298. The drug acts as a selective inhibitor of FAAH, which potently increases hippocampal levels of AEA, OEA and PEA in mice. Despite elevating eCB levels, SSR411298 did not mimic the interoceptive state or produce the behavioral side-efects (memory defcit and motor impairment) evoked by direct-acting cannabinoids. When SSR411298 was tested in models of anxiety, it only exerted clear anxiolytic-like efects under highly aversive conditions following exposure to a traumatic event, such as in the mouse defense test battery and social defeat procedure. Results from experiments in models of depression showed that SSR411298 produced robust antidepressant-like activity in the rat forced-swimming test and in the mouse chronic mild stress model, restoring notably the development of inadequate coping responses to chronic stress. This preclinical profle positions SSR411298 as a promising drug candidate to treat diseases such as post-traumatic stress disorder, which involves the development of maladaptive behaviors. Te endocannabinoid (eCB) system is formed by two G protein-coupled receptors, CB1 and CB2, and their main transmitters, N-arachidonoylethanolamine (anandamide; AEA) and 2-arachidonoyglycerol (2-AG)1. -

N-Arachidonoyl Dopamine Modulates Acute Systemic Inflammation Via Nonhematopoietic TRPV1

N-Arachidonoyl Dopamine Modulates Acute Systemic Inflammation via Nonhematopoietic TRPV1 This information is current as Samira K. Lawton, Fengyun Xu, Alphonso Tran, Erika of October 1, 2021. Wong, Arun Prakash, Mark Schumacher, Judith Hellman and Kevin Wilhelmsen J Immunol 2017; 199:1465-1475; Prepublished online 12 July 2017; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1602151 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/199/4/1465 Downloaded from Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2017/07/12/jimmunol.160215 Material 1.DCSupplemental http://www.jimmunol.org/ References This article cites 69 articles, 11 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/199/4/1465.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision by guest on October 1, 2021 • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Author Choice Freely available online through The Journal of Immunology Author Choice option Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2017 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology N-Arachidonoyl Dopamine Modulates Acute Systemic Inflammation via Nonhematopoietic TRPV1 Samira K. -

The Endogenous Cannabinoid 2-Arachidonoylglycerol Is Intravenously Self-Administered by Squirrel Monkeys

The Journal of Neuroscience, May 11, 2011 • 31(19):7043–7048 • 7043 Brief Communications The Endogenous Cannabinoid 2-Arachidonoylglycerol Is Intravenously Self-Administered by Squirrel Monkeys Zuzana Justinova´,1,2 Sevil Yasar,3 Godfrey H. Redhi,1 and Steven R. Goldberg1 1Preclinical Pharmacology Section, Behavioral Neuroscience Research Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Baltimore, Maryland 21224, 2Maryland Psychiatric Research Centre, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21228, and 3Division of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21224 Two endogenous ligands for cannabinoid CB1 receptors, anandamide (N-arachidonoylethanolamine) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), have been identified and characterized. 2-AG is the most prevalent endogenous cannabinoid ligand in the brain, and electrophysiological studies suggest 2-AG, rather than anandamide, is the true natural ligand for cannabinoid receptors and the key endocannabinoid involved in retrograde signaling in the brain. Here, we evaluated intravenously administered 2-AG for reinforcing effects in nonhuman primates. Squirrel monkeys that previously self-administered anandamide or nicotine under a fixed-ratio schedule with a 60 s timeout after each injection had their self-administration behavior extinguished by vehicle substitution and were then given the opportunity to self-administer 2-AG. Intravenous 2-AG was a very effective reinforcer of drug-taking behavior, maintaining higher numbers of self-administered injections per session and higher rates of responding than vehicle across a wide range of doses. To assess involvement of CB1 receptors in the reinforcing effects of 2-AG, we pretreated monkeys with the cannabinoid CB1 receptor inverse agonist/antagonist rimonabant [N-piperidino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4- dichlorophenyl)-4-methylpyrazole-3-carboxamide]. -

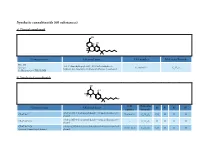

Synthetic Cannabinoids (60 Substances) A) Classical Cannabinoid

Synthetic cannabinoids (60 substances) a) Classical cannabinoid OH H OH H O Common name Chemical name CAS number Molecular Formula HU-210 3-(1,1’-dimethylheptyl)-6aR,7,10,10aR-tetrahydro-1- Synonym: 112830-95-2 C H O hydroxy-6,6-dimethyl-6H-dibenzo[b,d]pyran-9-methanol 25 38 3 11-Hydroxy-Δ-8-THC-DMH b) Nonclassical cannabinoids OH OH R2 R3 R4 R1 CAS Molecular Common name Chemical name R1 R2 R3 R4 number Formula rel-2[(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methyloctan- 2- yl) CP-47,497 70434-82-1 C H O CH H H H phenol 21 34 2 3 rel-2[(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methylheptan- 2- yl) CP-47,497-C6 - C H O H H H H phenol 20 32 2 CP-47,497-C8 rel-2- [(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methylnonan- 2- yl) 70434-92-3 C H O C H H H H Synonym: Cannabicyclohexanol phenol 22 36 2 2 5 CAS Molecular Common name Chemical name R1 R2 R3 R4 number Formula rel-2[(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxycyclohexyl]- 5- (2- methyldecan- 2- yl) CP-47,497-C9 - C H O C H H H H phenol 23 38 2 3 7 rel-2- ((1 R,2 R,5 R)-5- hydroxy- 2- (3- hydroxypropyl)cyclohexyl)- 3-hydroxy CP-55,940 83003-12-7 C H O CH H H 5-(2- methyloctan- 2- yl)phenol 24 40 3 3 propyl rel-2- [(1 S,3 R)-3- hydroxy-5,5-dimethylcyclohexyl]- 5- (2- Dimethyl CP-47,497-C8 - C H O C H CH CH H methylnonan-2- yl)phenol 24 40 2 2 5 3 3 c) Aminoalkylindoles i) Naphthoylindoles 1' R R3' R2' O N CAS Molecular Common name Chemical name R1’ R2’ R3’ number Formula [1-[(1- methyl- 2- piperidinyl)methyl]- 1 H-indol- 3- yl]- 1- 1-methyl-2- AM-1220 137642-54-7 C H N O H H naphthalenyl-methanone 26 26 2 piperidinyl -

The Cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 Prevents Neuroendocrine Differentiation of Lncap Prostate Cancer Cells

OPEN Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2016) 19, 248–257 www.nature.com/pcan ORIGINAL ARTICLE The cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 prevents neuroendocrine differentiation of LNCaP prostate cancer cells C Morell1, A Bort1, D Vara2, A Ramos-Torres1, N Rodríguez-Henche1 and I Díaz-Laviada1 BACKGROUND: Neuroendocrine (NE) differentiation represents a common feature of prostate cancer and is associated with accelerated disease progression and poor clinical outcome. Nowadays, there is no treatment for this aggressive form of prostate cancer. The aim of this study was to determine the influence of the cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 (WIN, a non-selective cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptor agonist) on the NE differentiation of prostate cancer cells. METHODS: NE differentiation of prostate cancer LNCaP cells was induced by serum deprivation or by incubation with interleukin-6, for 6 days. Levels of NE markers and signaling proteins were determined by western blotting. Levels of cannabinoid receptors were determined by quantitative PCR. The involvement of signaling cascades was investigated by pharmacological inhibition and small interfering RNA. RESULTS: The differentiated LNCaP cells exhibited neurite outgrowth, and increased the expression of the typical NE markers neuron-specific enolase and βIII tubulin (βIII Tub). Treatment with 3 μM WIN inhibited NK differentiation of LNCaP cells. The cannabinoid WIN downregulated the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, resulting in NE differentiation inhibition. In addition, an activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) was observed in WIN-treated cells, which correlated with a decrease in the NE markers expression. Our results also show that during NE differentiation the expression of cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 dramatically decreases. -

Grunddokument 2

The cellular processing of the endocannabinoid anandamide and its pharmacological manipulation Lina Thors Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Neuroscience SE-901 87 Umeå, Sweden Umeå 2009 1 Copyright©Lina Thors ISBN: 978-91-7264-732-9 ISSN: 0346-6612 Printed by: Print & Media Umeå, Sweden 2009 2 Abstract Anandamide (arachidonoyl ethanolamide, AEA) and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) exert most of their actions by binding to cannabinoid receptors. The effects of the endocannabinoids are short-lived due to rapid cellular accumulation and metabolism, for AEA, primarily by the enzymes fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH). This has led to the hypothesis that by inhibition of the cellular processing of AEA, beneficial effects in conditions such as pain and inflammation can be enhanced. The overall aim of the present thesis has been to examine the mechanisms involved in the cellular processing of AEA and how they can be influenced pharmacologically by both synthetic natural compounds. Liposomes, artificial membranes, were used in paper I to study the membrane retention of AEA. The AEA retention mimicked the early properties of AEA accumulation, such as temperature- dependency and saturability. In paper II, FAAH was blocked by a selective inhibitor, URB597, and reduced the accumulation of AEA into RBL2H3 basophilic leukaemia cells by approximately half. Treating intact cells with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein, an isoflavone found in soy plants and known to disrupt caveolae-related endocytosis, reduced the AEA accumulation by half, but in combination with URB597 no further decrease was seen. Further on, the effects of genistein upon uptake were secondary to inhibition of FAAH. -

Cannabinoids: Novel Molecules with Significant Clinical Utility

CANNABINOIDS: NOVEL MOLECULES WITH SIGNIFICANT CLINICAL UTILITY NOEL ROBERT WILLIAMS MD FACOG DIRECTOR OPTIMAL HEALTH ASSOCIATES OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLAHOMA How Did We Get Here? • In November 2012 Tikun Olam, an Israeli medical cannabis facility, announced a new strain of the plant which has only CBD as an active ingredient, and virtually no THC, providing some of the medicinal benefits of cannabis without euphoria. The Researchers said the cannabis plant, enriched with CBD, “can be used for treating diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, colitis, liver inflammation, heart disease and diabetes.” Cannabis CBD like in this article is legally derived from the hemp plant. • CBD is the major non-psychoactive component of Cannabis Sativa (Hemp). Hemp plants are selectively developed and grown to contain high amounts of CBD and very low amounts of the psychoactive component THC found in marijuana. A few CBD oil manufacturers further purify their products to contain high amounts of CBD and no THC. 2014 Farm Bill Terminology • Active Ingredient • Zero THC • Cannabidiol • Isolate • PCR – Phytocannabinoid-Rich • Hemp Oil Extract • “Recommendation” vs. “Prescribed” • Full Spectrum Endocannabinoids (AEA) Phytocannabinoids Full Spectrum & Active Ingredient • CBD – Cannabidiol • A major phytocannabinoid, accounting for as much as 85% of the plant’s extract • CBC – Cannabichromene • Anti-inflammatory & anti-fungal effects have been seen • CBG – Cannabigerol • The parent molecule from which many other cannabinoids are made • CBDV – Cannabidivarin • A homolog of CBD that has been reported to have powerful anti-convulsive effects • CBN – Cannabinol • Sleep & Appetite regulation • Terpenes • Wide spectrum of non-psychoactive molecules that are know to act on neural receptors and neurotransmitters, enhance norepinephrine activity, and potentially increases dopamine activity. -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Neuropharmacology

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Neuropharmacology. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 January 1. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Neuropharmacology. 2008 January ; 54(1): 129±140. The endogenous cannabinoid anandamide has effects on motivation and anxiety that are revealed by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibition Maria Schermaa,b, Julie Medaliea, Walter Frattab, Subramanian K. Vadivelc, Alexandros Makriyannisc, Daniele Piomellid, Eva Mikicse, Jozsef Hallere, Sevil Yasarf, Gianluigi Tandag, and Steven R. Goldberga,* aPreclinical Pharmacology Section, Behavioral Neuroscience Research Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA bB.B. Brodie Department of Neuroscience, University of Cagliari, Italy cCenter for Drug Discovery, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA dDepartment of Pharmacology, University of California, Irvine, USA eInstitute of Experimental Medicine, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary fDivision of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA gPsychobiology Section, Medications Discovery Research Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA Summary Converging evidence suggests that the endocannabinoid system is an important constituent of neuronal substrates involved in brain reward processes and emotional responses to stress. Here, we evaluated motivational effects of intravenously administered anandamide, an endogenous ligand for cannabinoid-CB1 receptors, in Sprague-Dawley rats, using a place-conditioning procedure in which drugs abused by humans generally produce conditioned place preferences (reward). Anandamide (0.03 to 3mg/kg intravenous) produced neither conditioned place preferences nor aversions. -

208614788.Pdf

0022-3565/02/3013-1020–1024$7.00 THE JOURNAL OF PHARMACOLOGY AND EXPERIMENTAL THERAPEUTICS Vol. 301, No. 3 Copyright © 2002 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 0/986104 JPET 301:1020–1024, 2002 Printed in U.S.A. Characterization of a Novel Endocannabinoid, Virodhamine, with Antagonist Activity at the CB1 Receptor AMY C. PORTER, JOHN-MICHAEL SAUER, MICHAEL D. KNIERMAN, GERALD W. BECKER, MICHAEL J. BERNA, JINGQI BAO, GEORGE G. NOMIKOS, PETRA CARTER, FRANK P. BYMASTER, ANDREA BAKER LEESE, and CHRISTIAN C. FELDER Lilly Research Laboratories, Neuroscience Division (A.C.P., G.G.N., P.C., F.P.B., A.B.L., C.C.F.), Drug Disposition (J.-M.S., M.J.B., J.B.), and Research Technologies and Proteins (M.D.K., G.W.B.), Eli Lilly & Co., Lilly Corporate Center, Indianapolis, Indiana Received December 19, 2001; accepted February 18, 2002 This article is available online at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org Downloaded from ABSTRACT The first endocannabinoid, anandamide, was discovered in rodhamine concentrations were 2- to 9-fold higher than anan- 1992. Since then, two other endocannabinoid agonists have damide. In contrast to previously described endocannabinoids, been identified, 2-arachidonyl glycerol and, more recently, no- virodhamine was a partial agonist with in vivo antagonist activ- ladin ether. Here, we report the identification and pharmaco- ity at the CB1 receptor. However, at the CB2 receptor, vi- 14 logical characterization of a novel endocannabinoid, vi- rodhamine acted as a full agonist. Transport of [ C]anandam- jpet.aspetjournals.org rodhamine, with antagonist properties at the CB1 cannabinoid ide by RBL-2H3 cells was inhibited by virodhamine. -

JPET 143487 Synergy Between Enzyme Inhibitors of Fatty Acid

JPET Fast Forward. Published on January 9, 2009 as DOI:10.1124/jpet.108.143487 JPET 143487 Synergy between enzyme inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase and cyclooxygenase in visceral nociception* Pattipati S. Naidu, Lamont Booker, Benjamin F. Cravatt, and Aron H. Lichtman Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Medical College of Virginia Campus, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298-0613. (P.S.N., L.B., and A.H.L.) The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and Departments of Cell Biology and Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 N. Torrey Pines Rd. La Jolla, CA 92037. (B.F.C.) 1 Copyright 2009 by the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. JPET 143487 Running Title: Synergy between FAAH and COX inhibitors Corresponding Author: Aron H. Lichtman P.O. Box 980613 Richmond, VA 23298-0613 Telephone: 804-828-8480 Facsimile: 804-828-2117 E-mail: [email protected] Number of text pages: 16 Number of figures: 6 Number of tables: 1 Number of references: 38 Number of words in the Abstract: 247 Number of words in the Introduction: 720 Number of words in the Discussion: 1463 Abbreviations: CB1, cannabinoid receptor 1; CB2 cannabinoid receptor 2; CNS, central nervous system; FAAH, fatty acid amide hydrolase, COX, cyclooxygenase; NSAIDs, Nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs; URB597, 3'-carbamoyl-biphenyl-3-yl-cyclohexylcarbamate Recommended section assignment: Behavioral pharmacology 2 JPET 143487 Abstract The present study investigated whether inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), the enzyme responsible for anandamide catabolism, produces antinociception in the acetic acid- induced abdominal stretching model of visceral nociception. Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of FAAH reduced acetic acid-induced abdominal stretching.