Peter S. Beagle's Transformations of the Mythic Unicorn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rose Gardner Mysteries

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. Est. 1994 RIGHTS CATALOG 2019 JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. 49 W. 45th St., 12th Floor, New York, NY 10036-4603 Phone: +1-917-388-3010 Fax: +1-917-388-2998 Joshua Bilmes, President [email protected] Adriana Funke Karen Bourne International Rights Director Foreign Rights Assistant [email protected] [email protected] Follow us on Twitter: @awfulagent @jabberworld For the latest news, reviews, and updated rights information, visit us at: www.awfulagent.com The information in this catalog is accurate as of [DATE]. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. Table of Contents Table of Contents Author/Section Genre Page # Author/Section Genre Page # Tim Akers ....................... Fantasy..........................................................................22 Ellery Queen ................... Mystery.........................................................................64 Robert Asprin ................. Fantasy..........................................................................68 Brandon Sanderson ........ New York Times Bestseller.......................................51-60 Marie Brennan ............... Fantasy..........................................................................8-9 Jon Sprunk ..................... Fantasy..........................................................................36 Peter V. Brett .................. Fantasy.....................................................................16-17 Michael J. Sullivan ......... Fantasy.....................................................................26-27 -

Rape of the Hobbit

Volume 1 Number 2 Article 10 Spring 4-15-1969 Rape of The Hobbit Fred Brenion Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Brenion, Fred (1969) "Rape of The Hobbit," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 1 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol1/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract The Hobbit. Dramatic production. Additional Keywords Review; The Hobbit; Drama; Production This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol1/iss2/10 Rape of The Hobbit Come to Middle Earth - An Original Musical reported and reviewed by Fred Brenion As most members of The Mythopoeic Society probably know by now, a musical play has been touring the Southern California area, based on The Hobbit by jJ.R.R. -

Conlan Press Release: Immediate Contact: Connor Cochran Phone: 925 260-2725 Fax: 415 358-8060 Email: [email protected]

Conlan Press Release: Immediate Contact: Connor Cochran Phone: 925 260-2725 Fax: 415 358-8060 Email: [email protected] FANS HELP WORLD-FAMOUS AUTHOR PETER S. BEAGLE WHEN THEY GET THE NEW 25TH ANNIVERSARY DVD EDITION OF THE LAST UNICORN THROUGH CONLAN PRESS On 2/6/07 Lionsgate will release The Last Unicorn: 25th Anniversary Edition — a widescreen digitally remastered DVD version of the animated classic, including additional features and material — with special Conlan Press distribution on behalf of author and screenwriter Peter S. Beagle. The Last Unicorn has been a worldwide success in its theatrical film, cable, VHS, and DVD versions. But to date, author and screenwriter Peter S. Beagle has never been paid anything from the millions of dollars the film has earned. Now, by special arrangement with Lionsgate Entertainment, customers can ensure that more than half their purchase price of this 25th Anniversary Edition DVD will go directly to support Peter S. Beagle and his projects by buying through Conlan Press (www.conlanpress.com). Although The Last Unicorn: 25th Anniversary Edition will be available from all major DVD retailers, only purchases made through Conlan Press (www.conlanpress.com) will benefit Mr. Beagle. The Last Unicorn: 25th Anniversary Edition DVD features an all-star cast of voice talent, and songs performed by the band America. Starring Christopher Lee, Mia Farrow, and Academy Award® nominees Alan Arkin, Angela Lansbury, and Jeff Bridges, the movie tells the powerful tale of a unicorn who sets out on a quest to find her lost brothers and sisters. The film’s character design and animation were done by the Japanese artists who went on to become the core of Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli (My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away). -

Middle and Junior High Core Collection

MIDDLE AND JUNIOR HIGH CORE COLLECTION A Selection Guide 2012 SUPPLEMENT TO THE TENTH EDITION EDITED BY EVE-MARIE MILLER, CHRISTI SHOWMAN FARRAR AND LIZA OLDHAM H. W. WILSON A Division of EBSCO Publishing, Inc. IPSWICH, MASSACHUSETTS Copyright © 2013 by H. W. Wilson, A Division of EBSCO Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. For permissions requests, contact [email protected]. Library of Congress Control Number 2009027506 International Standard Book Number: 978-0-8242-1102-8 Printed in the United States of America Abridged Dewey Decimal Classification and Relative Index, Edition 15 is © 2004–2012 OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. Used with Permission. DDC, Dewey, Dewey Decimal Classification, and WebDewey are registered trademarks of OCLC. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface v Directions for Use vi Part 1. Classified Collection 1 Part 2. Author, Title, and Subject Index 133 PREFACE Middle and Junior High Core Collection is a selective list of books recommended for young people in grades five through nine, together with professional aids for librarians and library media specialists. This 2012 Supplement is intended for use with the Tenth Edition of the Collection and contains entries for approximately 500 titles. The items in the Collection are considered appropriate for middle and junior high school libraries, though some titles overlap in their reading level with Children’s Core Collection and others with Senior High Core Collection. -

Download the Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle

The Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle Ebook The Last Unicorn currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Last Unicorn please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Hardcover:::: 152 pages+++Publisher:::: IDW Publishing; First Thus edition (February 8, 2011)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1600108512+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1600108518+++Product Dimensions::::6.7 x 0.7 x 10.4 inches++++++ ISBN10 1600108512 ISBN13 978-1600108 Download here >> Description: Whimsical. Lyrical. Poignant. Adapted for the first time from the acclaimed and beloved novel by Peter S. Beagle, The Last Unicorn is a tale for any age about the wonders of magic, the power of love, and the tragedy of loss. The unicorn, alone in her enchanted wood, discovers that she may be the last of her kind. Reluctant at first, she sets out on a journey to find her fellow unicorns, even if it means facing the terrifying anger of the Red Bull and malignant evil of the king who wields his power.Adapted by Peter B. Gillis and lushly illustrated by Renae De Liz and Ray Dillon. Youve probably seen the animated film from 1982. Rankin/Bass really knew what they were doing and the film remains one of your favorites to this day, almost 30 years from the first time you saw it. Somehow you never got around to reading the book. Maybe you didnt know there was a book. Maybe you got waylaid by stories of travel through a wardrobe, or you went on a quest to reclaim dragon treasure. -

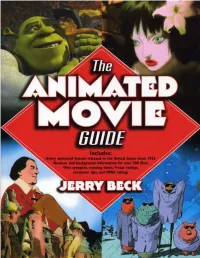

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

January, 2013

בס"ד Science-Fiction Fanzine Vol. XXV, No. 1; January, 2013 The Israeli Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy תחרות הסיפורים של "עולמות" תחרות הסיפורים של כנס "עולמות" נפתחת, ואנחנו מזמינים אתכם לשנס מותניים, לחדד מוחות ועטים ולכתוב לנו על נושא הכנס: "מנהיגים ומורדים". באתר האגודה ניתן למצוא את כל הפרטים, יחד עם תקנון התחרות. אתר "היה יהיה" ממשיך להתחדש, ומקבל כתובת חדשה! אתר "היה יהיה" עבר דירה, ועכשיו תוכלו למצוא אותו בכתובת: annual.sf-f.org.il בימים אלו עובר אתר השנתון מקצה שיפורים וכעת ניתן למצוא בו מידע על האסופות, הסיפורים והסופרים, קישורים לסיפורים מהאסופות שהתפרסמו ברשת ופרטים בנוגע להגשת סיפורים. בקרוב אף יהיה ניתן לקנות את האסופות ישירות דרך האתר. מועדון הקריאה של חודש ינואר יעסוק ב-התלקחות מאת סוזן קולינס )כנרת זמורה ביתן, 1122(, זוכה פרס גפן לשנת 1121. מועדון הקריאה בת"א יתקיים ביום ראשון, 11.2.22, בשעה 23:21 ב"קפה גרג", ויצמן 1 )פינת שאול המלך, מול בית המשפט(. המקום כשר. מנחה: ליאת שחר. ב11.2.22 יתקיים מועדון קריאה גם בירושלים, בהנחיית מריה ציבלין, פרטים מדויקים )מקום ושעה( יפורסמו בהמשך באתר האגודה. לפרטים והרשמה אפשר לפנות למנחת המועדון בירושלים. לצורך היערכות למספר המשתתפים, יש להירשם מראש דרך הדוא"ל של המנחה. כמו כן, רצוי להביא למפגש עותק של הספר. הכניסה חופשית ואינה כרוכה בתשלום, בחברות באגודה, או בהגעה למפגשים נוספים. מועדון חודש פברואר יעסוק בספרו של טד צ'יאנג סיפורי חייך ואחרים. המעוניינים להנחות מועדוני קריאה במרכז או בכל רחבי הארץ, על ספרים לפי בחירתם, מוזמנים לפנות בדוא"ל למרכזת הפרויקט, דפנה קירש. לקבלת עדכונים שוטפים על מפגשי מועדון הקריאה ברחבי הארץ, ניתן להצטרף לרשימת התפוצה של מועדון הקריאה בדוא"ל, או לעשות "לייק" לדף האגודה בפייסבוק. -

10 Animated Fantasy Films

10 ANIMATED FANTASY FILMSBy Bryan BEOWULF (2007)☐ After Robert Zemeckis journeyed into the Uncanny Valley of motion capture animation withThe Polar Express, he found an improved (if still creepy) look for this epic fantasy painting of a movie, with spectacular camera moves, some gore and a smart script by Pulp Fiction co-writer Roger Avary and The Sandman creator Neil Gaiman. Crispin "George McFly" Glover reunites with the director to bring his trademark weirdness to the monster, Grendel. THE BLACK CAULDRON (1985)☐ A few years before The Little Mermaid, when Disney was still trying to figure out what to do post-Walt, they took a big swing with this non-musical and so-scary-it-got-a-PG-rating (gasp) fantasy based on books by Lloyd Alexander. Though considered a flop at the time it holds up well because of its gorgeous background paintings and great animation of skeletons and ghouls. FIRE AND ICE (1983) ☐ Ralph Bakshi (whoseLord of the Rings could be on this list too) collaborated with the legendary Conan cover painter Frank Frazetta to make this rotoscoped barbarian film. They shot a bunch of people running around with furs and battle axes and then traced them onto animation cels painted up like Frazetta’s art. THEFLIGHT OF DRAGONS (1982)☐ Rankin-Bass, who blessed the world with everything from Heat Miser to Thundercats, also made a series of made-for-TV animated fantasies. The Hobbit and The Return of the King were followed by this exploration of the magic/science dichotomy. John Ritter voices a Boston writer transported from the ‘80s to a time of wizards and dragons. -

The Hunt of the Unicorn: Tapestry Copies Made for Stirling Castle, Scotland

The Hunt of the Unicorn: Tapestry Copies Made for Stirling Castle, Scotland by Amy Beingessner A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History and Visual Culture Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Amy Beingessner, May, 2015 ABSTRACT THE HUNT OF THE UNICORN: TAPESTRY COPIES MADE FOR STIRLING CASTLE, SCOTLAND Amy Beingessner Advisor: University of Guelph, 2015 Professor S. A. Hickson In 2014 the West Dean Tapestry Studio in England completed a commission for Historic Scotland, an agency of the Scottish government, to reproduce the late fifteenth-century Hunt of the Unicorn tapestry series on permanent display at the Cloisters Museum in New York City. The purpose of Historic Scotland’s reproductions is to heighten the tourist’s experience of authenticity in the Renaissance apartments at Stirling Castle, Scotland. This thesis explores Historic Scotland’s decision to reproduce The Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries for the renovation of Stirling Castle’s royal apartments, and how this representation of Scottish heritage and identity challenges traditional boundaries of authorship and authenticity. Applying the concept of the simulacrum, specifically through the writing of Jean Baudrillard and Gilles Deleuze, the Unicorn tapestries are analyzed based on the contexts and authorities that inform perceptions of their status as either copies or originals, revealing authenticity to be a perceived construction. iii Table of Contents Page List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................... -

The Evolution of Modern Fantasy from Antiquarianism to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

Copyrighted Material - 9781137518088 The Evolution of Modern Fantasy From Antiquarianism to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series Jamie Williamson Copyrighted Material - 9781137518088 Copyrighted Material - 9781137518088 the evolution of modern fantasy Copyright © Jamie Williamson, 2015. All rights reserved. First published in 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States— a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN: 978- 1- 137- 51808- 8 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Williamson, Jamie. The evolution of modern fantasy : from antiquarianism to the Ballantine adult fantasy series / by Jamie Williamson. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 1- 137- 51808- 8 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Fantasy literature— History and criticism. I. Title. PN56.F34W55 2015 809.3'8766— dc23 2015003219 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. Design by Scribe Inc. First edition: July 2015 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Copyrighted Material - 9781137518088 Copyrighted -

Locus Magazine

T A B L E o f C O N T E N T S April 2013 • Issue 627 • Vol. 70 • No. 4 CHARLES N. BROWN 46th Year of Publication • 30-Time Hugo Winner Founder Cover and Interview Designs by Francesca Myman (1968-2009) LIZA GROEN TROMBI Editor-in-Chief KIRSTEN GONG-WONG Managing Editor MARK R. KELLY Locus Online Editor-in-Chief CAROLYN F. CUSHMAN TIM PRATT Senior Editors FRANCESCA MYMAN Design Editor HEATHER SHAW Assistant Editor JONATHAN STRAHAN Reviews Editor TERRY BISSON GWENDA BOND GARDNER DOZOIS AMY GOLDSCHLAGER CECELIA HOLLAND RICH HORTON RUSSELL LETSON I N T E R V I E W S ADRIENNE MARTINI FAREN MILLER Terry Bisson: Personal Alternate History / 6 GARY K. WOLFE Libba Bray: Eco-Friendly Fembot Who Survives on the Tears of Teen Girls / 57 Contributing Editors KAREN BURNHAM P E O P L E & P U B L I S H I N G / 8 Roundtable Blog Editor Notes on milestones, awards, books sold, etc., with news this issue about Alex Bledsoe, Ginjer WILLIAM G. CONTENTO Buchanan and Carl Sagan, Cherie Priest, Elizabeth Bear, Terry Pratchett, and many others. Computer Projects Locus, The Magazine of the Science Fiction & Fantasy M A I N S T O R I E S / 5 & 10 Field (ISSN 0047-4959), is published monthly, at $7.50 per copy, by Locus Publications, 34 Ridgewood Lane, Oakland CA 94611. Please send all mail to: Kiernan and Salaam Win Tiptree Awards • 2012 Kitschies Winners • 2013 Philip K. Dick Award Locus Publications, PO Box 13305, Oakland CA Judges • SFWA vs. -

Travis Ashmore Conversation About “The Last Unicorn” and Other Writings by John C

PETER BEAGLE/ Travis Ashmore Conversation about “The Last Unicorn” and Other writings By John C. Tibbetts Raven Bookstore, Lawrence, KS, 13 April 2015 [begins after a brief conversation with his tour manager] JOHN TIBBETTS: …and I turn to Peter S. Beagle now in Lawrence, Kansas at the Raven Bookstore, thinking that you must have heard this story many times before, huh? PETER BEAGLE: Oh, any number of times but, in fact, my background is different from Travis’s but all the same I was the kid who read everything all the time and who certainly escaped from his own weirdness and his, into another neighborhood than my own and never, the difference is I never paid much attention to “The Last Unicorn.” It had been such a nightmare to write that I just wanted to get on to something else and try feeding my kids with some other book because that was most of it, being professional, is the only way I knew to make a living and what mattered really was putting bread on the table. A book that flows with such lyric grace is a nightmare to write? It’s supposed to look like that. (laughter) (indecipherable) Yes, exactly. One thing I knew growing up with artists like my uncles and writers whom I knew and teachers, my favorite cousin who was a choreographer, another who was a cellist with a very well known string quartet. The main thing was that you got up and did your work like everybody else. You didn’t give yourself airs. You just worked hard and, yes, the parallel I always use, frequently use, is watching Joe DiMaggio, whom I saw the last days of whom and Willie Mays, whose first days I saw.