ACFASP Scientific Review Hyperthermia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metabolomic Profiling Identifies a Novel Mechanism for Heat Stroke‑Related Acute Kidney Injury

MOLECULAR MEDICINE REPORTS 23: 241, 2021 Metabolomic profiling identifies a novel mechanism for heat stroke‑related acute kidney injury LING XUE1*, WENLI GUO2*, LI LI2, SANTAO OU2, TINGTING ZHU2, LIANG CAI3, WENFEI DING2 and WEIHUA WU2 Departments of 1Urology and 2Nephrology, Sichuan Clinical Research Center for Nephropathy, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University;3 Department of Nuclear Medicine, The Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, Sichuan 646000, P.R. China Received April 13, 2020; Accepted August 20, 2020 DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2021.11880 Abstract. Heat stroke can induce a systemic inflammatory factor mitochondria‑associated 2 (Aifm2), high‑mobility group response, which may lead to multi‑organ dysfunction including box 1 (HMGB1) and receptor for advanced glycosylation end acute kidney injury (AKI) and electrolyte disturbances. To products (RAGE). Liquid chromatography‑mass spectrometry investigate the pathogenesis of heat stroke (HS)‑related AKI, analysis was conducted to find differential metabolites and a mouse model of HS was induced by increasing the animal's signaling pathways. The HS mouse model was built success‑ core temperature to 41˚C. Blood samples obtained from the fully, with significantly increased creatinine levels detected tail vein were used to measure plasma glucose and creati‑ in the serum of HS mice compared with controls, whereas nine levels. Micro‑positron emission tomography‑computed micro‑PET/CT revealed active metabolism in the whole tomography (micro‑PET/CT), H&E staining and trans‑ body of HS mice. H&E and TUNEL staining revealed that mission electron microscopy were conducted to examine the kidneys of HS mice exhibited signs of hemorrhage and metabolic and morphological changes in the mouse kidneys. -

Prevention and Management of Heat-Related Illness

PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT OF HEAT-RELATED ILLNESS Federal Bureau of Prisons Clinical Guidance DECEMBER 2017 Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) Clinical Guidance is made available to the public for informational purposes only. The BOP does not warrant this guidance for any other purpose, and assumes no responsibility for any injury or damage resulting from the reliance thereof. Proper medical practice necessitates that all cases are evaluated on an individual basis and that treatment decisions are patient- specific. Consult the BOP Health Management Resources Web page to determine the date of the most recent update to this document: http://www.bop.gov/resources/health_care_mngmt.jsp Federal Bureau of Prisons Prevention and Management of Heat-Related Illness Clinical Guidance December 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................1 2. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY...............................................................................................................................1 3. RISK FACTORS FOR HRI ........................................................................................................................2 4. SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS ..........................................................................................................................3 5. EVALUATION.........................................................................................................................................5 6. TREATMENT..........................................................................................................................................6 -

HHE Report No. HETA-2018-0154-3361, Evaluation of Rhabdomyolysis and Heat Stroke in Structural Firefighter Cadets

Evaluation of Rhabdomyolysis and Heat Stroke in Structural Firefighter Cadets HHE Report No. 2018-0154-3361 November 2019 Authors: Judith Eisenberg, MD, MS Jessica F. Li, MSPH Karl D. Feldmann, MS, CIH Desktop Publisher: Jennifer Tyrawski Editor: Cheryl Hamilton Logistics: Donnie Booher, Kevin Moore Medical Field Assistance: Nonita Dhirar Data Support: Hannah Echt Keywords: North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) 922160 (Fire Protection), Structural Firefighter Training, Structural Firefighter Cadet Course, Heat, Heat-Related Illness, Heat Stroke, Rhabdomyolysis, Texas Disclaimer The Health Hazard Evaluation Program investigates possible health hazards in the workplace under the authority of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 [29 USC 669a(6)]. The Health Hazard Evaluation Program also provides, upon request, technical assistance to federal, state, and local agencies to investigate occupational health hazards and to prevent occupational disease or injury. Regulations guiding the Program can be found in Title 42, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 85; Requests for Health Hazard Evaluations [42 CFR Part 85]. Availability of Report Copies of this report have been sent to the employer, employees, and union at the plant. The state and local health departments and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration Regional Office have also received a copy. This report is not copyrighted and may be freely reproduced. Recommended Citation NIOSH [2019]. Evaluation of rhabdomyolysis and heat stroke in structural firefighter cadets. By Eisenberg J, Li JF, Feldmann KD. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Health Hazard Evaluation Report 2018-0154-3361, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/hhe/reports/pdfs/2018-0154-3361.pdf. -

Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments

Criteria for a Recommended Standard Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Cover photo by Thinkstock© Criteria for a Recommended Standard Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments Revised Criteria 2016 Brenda Jacklitsch, MS; W. Jon Williams, PhD; Kristin Musolin, DO, MS; Aitor Coca, PhD; Jung-Hyun Kim, PhD; Nina Turner, PhD DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted. Disclaimer Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations of websites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these websites. Ordering Information This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted. To receive NIOSH documents or other information about occupational safety and health topics, contact NIOSH at Telephone: 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636) TTY: 1-888-232-6348 E-mail: [email protected] or visit the NIOSH website at www.cdc.gov/niosh. For a monthly update on news at NIOSH, subscribe to NIOSH eNews by visiting www.cdc.gov/ niosh/eNews. Suggested Citation NIOSH [2016]. NIOSH criteria for a recommended standard: occupational exposure to heat and hot environments. By Jacklitsch B, Williams WJ, Musolin K, Coca A, Kim J-H, Turner N. -

Diagnostic Value of Procalcitonin in Patients with Heat Stroke

Arch Microbiol Immunology 2020; 4 (1): 001-010 DOI: 10.26502/ami.93650040 Research Article Diagnostic Value of Procalcitonin in Patients with Heat Stroke Xuan Song1, Xinyan Liu1, Huairong Wang2, Xiuyan Guo2, Maopeng Yang1, Daqiang Yang1, Yahu Bai3, Nana Zhang1, Chunting Wang4* 1Department of Intensive Care Unit, DongE Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Liaocheng, China. 2Education Department, DongE Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Liaocheng, China. 3Emergency Department, DongE Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Liaocheng, China. 4Department of Intensive Care Unit, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Shandong, China. *Corresponding Author: Chunting Wang, Department of Intensive Care Unit, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, 324 Jingwu Road, Jinan, Shandong Province, China, 250021, Tel: +86-17806359196; E-mail: [email protected] Received: 13 January 2020; Accepted: 23 January 2020; Published: 03 February 2020 Citation: Xuan Song, Xinyan Liu, Huairong Wang, Xiuyan Guo, Maopeng Yang, Daqiang Yang, Yahu Bai, Nana Zhang, Chunting Wang. Diagnostic Value of Procalcitonin in Patients with Heat Stroke. Arch Microbiol Immunology 2020; 4 (1): 001-010. Abstract (APACHE II) score and Multiple Organ Dysfunction Background: Heat stroke is a life-threatening disease, Score (MODS) were calculated within the first 24 hours but there is currently no biomarker to accurately assess of admission to the ICU. The ability of PCT, APACHE prognosis. II score, and MODS score to predict prognosis was assessed using a receiver operating characteristic curve Objective: To study whether serum procalcitonin (PCT) (ROC) and area under the curve (AUC) analyses. is an effective biomarker for evaluating the prognosis Result: There was no statistical difference in the PCT for patients with heat stroke. -

Relationship Between MH Susceptibility and Heat Or Exercise Related Rhabdomyolysis Posted in 2017

Relationship Between MH Susceptibility and Heat or Exercise Related Rhabdomyolysis Posted in 2017 Topic What is the relationship between malignant hyperthermia susceptibility and heat or exercise related rhabdomyolysis? Supporting Evidence Background: There is a poorly-defined relationship between MH susceptibility and the development of a non-anesthetic MH-like illness during conditions of heat, exercise, stress, or viral illness.1,2 This non-anesthetic-induced MH-like condition may demonstrate many of the same clinical signs as anesthetic-induced MH including hyperthermia, muscle rigidity, rhabdomyolysis, and life-threatening hyperkalemia. Animal and anecdotal human data suggest that dantrolene is effective in ameliorating consequences of heat stroke. Many questions remain. In the absence of previous diagnostic testing, when should patients with a history of a non-anesthetic MH-like syndrome related to external conditions be considered to be at special risk for MH when they present for general anesthesia? When should these patients be referred for diagnostic testing for MH susceptibility? Are patients with a suspected or proven susceptibility to MH at greater than normal risk of developing a non-anesthetic MH-like syndrome during non-extreme levels of exercise or heat exposure? If so, should their lifestyles be altered to avoid those conditions? Should competitive athletics be avoided? Discussion: The relationship between MH and non-anesthetic MH-like illnesses has been confirmed by experimental human4 and animal5 studies as well as -

Heat Related Illnesses

Heat Related Illnesses Refresher Course for the Family Physician 4/3/20 Brooks J. Obr MD MME University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Department of Emergency Medicine What we’ll cover… • Basics of heat related illnesses • Risk factors/etiology • Heat cramps • Prickly heat • Heat edema • Heat syncope • Heat exhaustion • Heat stroke • Workups, treatments/cooling measures, dispositions Let’s start with the basics… • Wide range of progressively more severe illnesses • Increasingly overwhelming heat stress • Basic dehydration Thermoregulatory dysfunction/organ failure • Normally, body temperature is maintained by balancing heat production with heat loss/dissipation Etiology • Pre-existing conditions hindering the body’s ability to dissipate heat predispose for heat-related illness • Age extremes • Dehydration (gastroenteritis, inadequate fluid intake, etc.) • Cardiovascular disease (CHF, CAD, etc.) • Obesity • Diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism, pheochromocytoma • Febrile illness • Skin diseases that hinder sweating (psoriasis, eczema, cystic fibrosis, scleroderma, etc.) Etiology • Pharmacologic contributors • Sympathomimetics • LSD, PCP, Cocaine • MAO inhibitors, antipsychotics, anxiolytics • Anticholinergics • Antihistamines • Beta-blockers • Diuretics • Laxatives • Drug/ETOH withdrawal Etiology • Environmental factors • Excessive heat/humidity • Prolonged exertion • Lack of mobility • Lack of air conditioning • Lack of acclimatization • Occlusive, nonporous clothing Pediatrics • A special note on pediatric patients: Children are at increased -

Heat Related Illness

Heat Related Illness With the return of warmer weather, Alberta Health Services EMS would like to remind citizens to stay safe in the heat and sun this summer. While children and the elderly can be more susceptible to the effects of heat, basic prevention measures should be taken by all to avoid a heat related illness during periods of hot and humid weather. Heat exhaustion First aid • Heat exhaustion can occur due to • First aid for all heat related excessive fluid loss during periods illness begins with removing or of prolonged sweating in a hot and / sheltering the patient from the or humid environment (indoors or hot environment. outdoors). • Remove excess or tight fitting • Patients may suffer headaches, clothing and allow them to rest in weakness, fatigue, nausea / a cool environment. vomiting, thirst, chills, and profuse • If the patient is conscious and sweating. alert, provide suitable fluids such as water, juice, or a sports drink. • The patient is usually cold and damp to the touch and the skin may • If you are concerned, seek appear pale or dusky gray. medical attention or call 9-1-1. Heat stroke Prevention • Stay well-hydrated by drinking • Heat stroke is a medical emergency plenty of water. that requires prompt treatment. It can • be fatal. Limit alcohol consumption as alcohol dehydrates you. • It occurs when the body can’t cool • Always wear a broad brimmed itself naturally (e.g. perspiration). The hat to keep the sun off your face body’s temperature will continue to and neck. rise to dangerous levels. • Apply waterproof sunscreen with • Due to severe dehydration and the an SPF of 50+, especially for inability to sweat the patient may children. -

Hyperthermia & Heat Stroke: Heat-Related Conditions

Hyperthermia & Heat Stroke: Heat-Related Conditions Joseph Rampulla, MS, APRN,BC eat-related conditions occur when excess heat taxes or overwhelms the body’s thermoregulatory mechanisms. Heat illness is preventable and occurs more Hcommonly than most clinicians realize. Heat illness most seriously affects the poor, urban-dwellers, young children, those with chronic physical and mental illnesses, substance abusers, the elderly, and people who engage in excessive physical The exposure to activity under harsh conditions. While considerable overlap occurs, the important the heat and the concrete during the syndromes are: heat stroke, heat exhaustion, and heat cramps. Heat stroke is a life- hot summer months places many rough threatening emergency and occurs when the loss of thermoregulatory control results sleepers at great risk in hyperpyrexia (very high fever) and severe damage to many internal organs. for heat stroke and hyperthermia. Photo by Epidemiology Sharon Morrison RN Heat illness is generally underreported, and the deaths than all other natural disasters combined in true incidence is unknown. Death rates from other the USA. The elderly, the very poor, and socially causes (e.g. cardiovascular, respiratory) increase isolated individuals are disproportionately affected during heat waves but are generally not reflected in by heat waves. For example, death records during the morbidity and mortality statistics related to heat heat waves invariably include many elders who died illness. Nonetheless, heat waves account for more alone in hot apartments. Age 65 years, chronic The Health Care of Homeless Persons - Part II - Hyperthermia and Heat Stroke 199 illness, and residence in a poor neighborhood are greater than 65. -

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome in the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Postgrad Med J 1997; 73: 779-784 (© The Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine, 1997 HIV medicine Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.73.866.779 on 1 December 1997. Downloaded from Neuroleptic malignant syndrome in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome Jose L Hemaindez, Luis Palacios-Araus, Santiago Echevarria, Andres Herran, Juan F Campo, Jose A Riancho Summary The neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a life-threatening process, Patients infected by the human typically, but not exclusively, induced by drugs of the neuroleptic group. Its immunodeficiency virus are pre- main clinical manifestations include fever, rigidity of skeletal muscles, disposed to many infectious and fluctuating consciousness and autonomic disturbances.' Since first described noninfectious complications and by Delay and Deniker in 1968,2 the syndrome has received increasing attention often receive a variety of drugs. and more than 1600 cases have been reported to date, including a few cases in Furthermore, they seem to have a patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).3-8 Never- particular susceptibility to idio- theless, outside psychiatry, the syndrome probably remains underdiagnosed, as syncratic adverse drug reactions. its manifestations may be also caused by other processes such as infections and It is therefore surprising that only neoplasms. Thus, a high index of suspicion is needed to not miss the diagnosis a few cases of the neuroleptic in medical patients. This is particularly important in patients infected by the malignant syndrome have been human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), who commonly suffer infectious described in patients with the complications but also often receive psychoactive drugs. This article reviews acquired immunodeficiency syn- the main features of NMS in AIDS patients. -

Heat Sepsis Precedes Heat Toxicity in the Pathophysiology of Heat Stroke—A New Paradigm on an Ancient Disease

antioxidants Review Heat Sepsis Precedes Heat Toxicity in the Pathophysiology of Heat Stroke—A New Paradigm on an Ancient Disease Chin Leong Lim Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore 308232, Singapore; [email protected]; Tel.: +65-659-239-31 Received: 15 September 2018; Accepted: 22 October 2018; Published: 25 October 2018 Abstract: Heat stroke (HS) is an ancient illness dating back more than 2000 years and continues to be a health threat and to cause fatality during physical exertion, especially in military personnel, fire-fighters, athletes, and outdoor laborers. The current paradigm in the pathophysiology and prevention of HS focuses predominantly on heat as the primary trigger and driver of HS, which has not changed significantly for centuries. However, pathological and clinical reports from HS victims and research evidence from animal and human studies support the notion that heat alone does not fully explain the pathophysiology of HS and that HS may also be triggered and driven by heat- and exercise-induced endotoxemia. Exposure to heat and exercise stresses independently promote the translocation of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from gram-negative bacteria in the gut to blood in the circulatory system. Blood concentration of LPS can increase to a threshold that triggers the systemic inflammatory response, leading to the downstream ramifications of cellular and organ damage with sepsis as the end point i.e., heat sepsis. The dual pathway model (DPM) of HS proposed that HS is triggered by two independent pathways sequentially along the core temperature continuum of >40 ◦C. HS is triggered by heat sepsis at Tc < 42 ◦C and by the heat toxicity at Tc > 42 ◦C, where the direct effects of heat alone can cause cellular and organ damage. -

TE 04 Hyperthermia Protocol Final 2017 Editable.Pdf

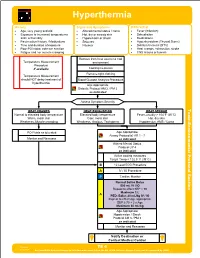

Hyperthermia History Signs and Symptoms Differential • Age, very young and old • Altered mental status / coma • Fever (Infection) • Exposure to increased temperatures • Hot, dry or sweaty skin • Dehydration and / or humidity • Hypotension or shock • Medications • Past medical history / Medications • Seizures • Hyperthyroidism (Thyroid Storm) • Time and duration of exposure • Nausea • Delirium tremens (DT's) • Poor PO intake, extreme exertion • Heat cramps, exhaustion, stroke • Fatigue and / or muscle cramping • CNS lesions or tumors Remove from heat source to cool Temperature Measurement environment Procedure if available Cooling measures Remove tight clothing Temperature Measurement should NOT delay treatment of Blood Glucose Analysis Procedure hyperthermia Age Appropriate Diabetic Protocol AM 2 / PM 2 as indicated Assess Symptom Severity Toxic HEAT CRAMPS HEAT EXHAUSTION HEAT STROKE Normal to elevated body temperature Elevated body temperature Fever, usually > 104°F (40°C) Warm, moist skin Cool, moist skin Hot, dry skin - Weakness, Muscle cramping Weakness, Anxious, Tachypnea Hypotension, AMS / Coma Section Environmental Protocol PO Fluids as tolerated Age Appropriate Airway Protocol(s) AR 1 - 7 Monitor and Reassess as indicated Altered Mental Status Protocol UP 4 as indicated Active cooling measures Target Temp < 102.5° F (39°C) B 12 Lead ECG Procedure A IV / IO Procedure P Cardiac Monitor A Age Appropriate Hypotension / Shock Protocol AM 5 / PM 3 as indicated Monitor and Reassess Notify Destination or Contact Medical Control Revised TE 4 09/29/2017 Any local EMS System changes to this document must follow the NC OEMS Protocol Change Policy and be approved by OEMS Hyperthermia Toxic - Environmental Protocol Environmental Section Protocol Pearls • Recommended Exam: Mental Status, Skin, HEENT, Heart, Lungs, Neuro • Extremes of age are more prone to heat emergencies (i.e.