Contemporary Financial Intermediation Dedication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World

EJIW Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World 5 volumes including index Executive Editor: Norman A. Stillman Th e goal of the Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World is to cover an area of Jewish history, religion, and culture which until now has lacked its own cohesive/discreet reference work. Th e Encyclopedia aims to fi ll the gap in academic reference literature on the Jews of Muslims lands particularly in the late medieval, early modern and modern periods. Th e Encyclopedia is planned as a four-volume bound edition containing approximately 2,750 entries and 1.5 million words. Entries will be organized alphabetically by lemma title (headword) for general ease of access and cross-referenced where appropriate. Additionally the Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World will contain a special edition of the Index Islamicus with a sole focus on the Jews of Muslim lands. An online edition will follow aft er the publication of the print edition. If you require further information, please send an e-mail to [email protected] EJIW_Preface.indd 1 2/26/2009 5:50:12 PM Australia established separate Sephardi institutions. In Sydney, the New South Wales Association of Sephardim (NAS), created in 1954, opened Despite the restrictive “whites-only” policy, Australia’s fi rst Sephardi synagogue in 1962, a Sephardi/Mizraḥi community has emerged with the aim of preserving Sephardi rituals in Australia through postwar immigration from and cultural identity. Despite ongoing con- Asia and the Middle East. Th e Sephardim have fl icts between religious and secular forces, organized themselves as separate congrega- other Sephardi congregations have been tions, but since they are a minority within the established: the Eastern Jewish Association predominantly Ashkenazi community, main- in 1960, Bet Yosef in 1992, and the Rambam taining a distinctive Sephardi identity may in 1993. -

The Present Truth for 1906

PRESENT . "Sanctify them through Thy truth: Thy Word is truth"st, SO VOL. 22. LONDON, THURSDAY, JUNE 2S, 1906. 402 THE PRESENT TRUTH. No. 26 In the Fulness of Time. the Scriptures say, enmity towards Him. The UPON that silent night, Protestant symbols and theologians, therefore, in When he looked forth and viewed the starry host, defining sin, not merely as selfishness, or the love What held Imperial Cmsar's mind the most ? A conquered world at peace, what bold surmise of the creature, or the love of the world, which Stirred his ambition to untried emprise? are only modes of its manifestation, but as the Reeked he of that poor province in the East, Of all Rome's pomp and empery the least ? want of conformity of an act, habit, or state of a man with the divine law, which is the revelation Upon that solemn night, Hoary with age and wise with eldest lore, of the divine nature, have in their support both Flowed her mysterious river, as of yore, reason and conscience. This doctrine of the From secret founts, parched Egpyt's thirst to slake ; Nor did the Sphinx her bond of silence break. nature of sin is fully sustained by the authority of Was there no sound of high angelic strain Scripture. The apostle John says that all want of In Memmon's music on the Theban plain ? conformity to law is sin. It seems that some Upon that starlit night in the apostle's day were disposed to limit the de- Did hallowed radiance, bright with light divine, Crown with new glory fair Athena's shrine? mands of divine law, and regard certain things not Star of the East did not thy golden beam specifically forbidden as lawful. -

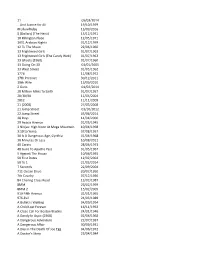

Title ID Titlename D0043 DEVIL's ADVOCATE D0044 a SIMPLE

Title ID TitleName D0043 DEVIL'S ADVOCATE D0044 A SIMPLE PLAN D0059 MERCURY RISING D0062 THE NEGOTIATOR D0067 THERES SOMETHING ABOUT MARY D0070 A CIVIL ACTION D0077 CAGE SNAKE EYES D0080 MIDNIGHT RUN D0081 RAISING ARIZONA D0084 HOME FRIES D0089 SOUTH PARK 5 D0090 SOUTH PARK VOLUME 6 D0093 THUNDERBALL (JAMES BOND 007) D0097 VERY BAD THINGS D0104 WHY DO FOOLS FALL IN LOVE D0111 THE GENERALS DAUGHER D0113 THE IDOLMAKER D0115 SCARFACE D0122 WILD THINGS D0147 BOWFINGER D0153 THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT D0165 THE MESSENGER D0171 FOR LOVE OF THE GAME D0175 ROGUE TRADER D0183 LAKE PLACID D0189 THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH D0194 THE BACHELOR D0203 DR NO D0204 THE GREEN MILE D0211 SNOW FALLING ON CEDARS D0228 CHASING AMY D0229 ANIMAL ROOM D0249 BREAKFAST OF CHAMPIONS D0278 WAG THE DOG D0279 BULLITT D0286 OUT OF JUSTICE D0292 THE SPECIALIST D0297 UNDER SIEGE 2 D0306 PRIVATE BENJAMIN D0315 COBRA D0329 FINAL DESTINATION D0341 CHARLIE'S ANGELS D0352 THE REPLACEMENTS D0357 G.I. JANE D0365 GODZILLA D0366 THE GHOST AND THE DARKNESS D0373 STREET FIGHTER D0384 THE PERFECT STORM D0390 BLACK AND WHITE D0391 BLUES BROTHERS 2000 D0393 WAKING THE DEAD D0404 MORTAL KOMBAT ANNIHILATION D0415 LETHAL WEAPON 4 D0418 LETHAL WEAPON 2 D0420 APOLLO 13 D0423 DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER (JAMES BOND 007) D0427 RED CORNER D0447 UNDER SUSPICION D0453 ANIMAL FACTORY D0454 WHAT LIES BENEATH D0457 GET CARTER D0461 CECIL B.DEMENTED D0466 WHERE THE MONEY IS D0470 WAY OF THE GUN D0473 ME,MYSELF & IRENE D0475 WHIPPED D0478 AN AFFAIR OF LOVE D0481 RED LETTERS D0494 LUCKY NUMBERS D0495 WONDER BOYS -

Movies, Only Orkers Crack Their Union Local’S Safe and Oct

The Accountant 556 Suspense A 13 6:15p; 18 9:25p; 19 7:30p; 24 8:55p; Treasury agent closes in on a brilliant 25 4:05p; 30 8:55p; 31 7:15p, PARMT freelance accountant who works for 241 Oct. 1 10:30p; 2 8p; 10 4p, 8:30p dangerous criminal organizations. Ben Adopt a Highway Drama When an daughter are held captive for 53 days by Affleck, Anna Kendrick, J.K. Simmons, ex-convict finds an abandoned baby in a A a former student. Corina Akeson, Reese Jon Bernthal. (2:30) ’16 TNT 138 Oct. 3 dumpster, he gains a new lease on life, 8p; 4 5:15p Abducted Action A war hero Alexander, Caroline Chan, Paralee Cook. deciding to dedicate himself to making 555 takes matters into his own hands (TV14, 2:00) ’19 LMN 109 Oct. 29 12p The Accused Drama Raped in a sure the child has a good life. Ethan A 56 bar, a woman hires a prosecutor who Hawke, Chris Sullivan, Christopher Hey- when a kidnapper snatches his Abduction Action A young man must young daughter during a home run for his life soon after learning that the goes after the patrons who encouraged erdahl, Elaine Hendrix. (NR, 1:21) ’19 invasion. Scout Taylor-Compton, Daniel folks who raised him are not his real par- her attackers. Kelly McGillis, Jodie Foster, STRZED 352 Oct. 8 8:11a; 20 4p Joseph, Michael Urie, Najarra Townsend. ents. Taylor Lautner, Lily Collins, Alfred Bernie Coulson, Leo Rossi. (2:00) ’88 Adopted in Danger Suspense A DNA (NR, 1:50) ’20 SHOS-E 323 Oct. -

Freud Upside Down: African American Literature and Psychoanalytic Culture

FREUD UPSIDE DOWN UPSIDE DOWN African American Literature the United States over course of Examining how psy- twentieth century. choanalysis has functioned as a cultural phenomenon within African American literary intellectual communities since the 1920s, Ahad lays out the historiography of and the intersections between literature psychoanalysis and considers the creative of African American writers approaches to psychological thought in their work and their personal lives. and Psychoanalytic Culture A volume in The New Black Studies Series, edited by Darlene Clark Hine and Dwight A. McBride Author photo by Cortez A. Carter A. Author photo by Cortez BADIA SAHAR AHAD is an assistant professor of English at Loyola University. BADIA SAHAR AHAD Freud Upside Down THE NEW BLACK STUDIES SERIES Edited by Darlene Clark Hine and Dwight A. McBride A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book. UPSIDE DOWN African American Literature and Psychoanalytic Culture BADIA SAHAR AHAD UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS Urbana, Chicago, and Spring!eld © !"#" by Badia Sahar Ahad All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America $ % & ' ! # ∞ )is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ahad, Badia Sahar. Freud upside down : African American literature and psychoanalytic culture / Badia Sahar Ahad. p. cm. — ()e new Black studies series) Includes bibliographical references and index. *+,- ./0-"-!%!-"'%11-# (cloth : alk. paper) #. American literature—African American authors—History and criticism. !. African Americans in literature. '. Psychology in literature. &. Psychoanalysis in literature. %. Race in literature. 1. Race—Psychological aspects. /. African Americans— Psychology. 0. Psychoanalysis and literature—United States. I. Title. -

M a G a Z I N

OCTOBER VOLUME 17 2017 MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 5 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers™ SPECIAL EDITION Roundtable Interview with Screenwriters Jupiter M. Makins, BD Young, Dwain Worrell, John Porter, and Jake Helgren PAGE 12 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! CONTENTS Contest/Festival Winners 4 Feature Scripts – FIND YOUR Grouped by Genre SCRIPTS FAST 5 ON INKTIP! Round Table Interview with Screenwriters Jupiter M. Makins, BD Young, Dwain Worrell, John Porter, INKTIP OFFERS: and Jake Helgren • Listings of Scripts and Writers Updated Daily 12 • Mandates Catered to Your Needs • Newsletters of the Latest Scripts and Writers • Personalized Customer Service Scripts Represented by Agents/Managers • Comprehensive Film Commissions Directory 59 Teleplays 64 You will find what you need on InkTip Sign up at InkTip.com! Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they place their scripts on our site. WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT INKTIP WRITERS “[InkTip] was the resource that connected “Without InkTip, I wouldn’t be a produced a director/producer with my screenplay screenwriter. I’d like to think I’d have – and quite quickly. I HAVE BEEN gotten there eventually, but INKTIP ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED CERTAINLY MADE IT HAPPEN WITH THE SUPPORT AND FASTER … InkTip puts screenwriters into OPPORTUNITIES I’ve gotten through contact with working producers.” being associated with InkTip.” – ANN KIMBROUGH, GOOD KID/BAD KID – DENNIS BUSH, LOVE OR WHATEVER “InkTip gave me the access that I needed “There is nobody out there doing more to directors that I BELIEVE ARE for writers then InkTip – nobody. PASSIONATE and not the guys trying THEY OPENED DOORS that I would to make a buck.” have never been able to open.” – DWAIN WORRELL, OPERATOR – RICKIE BLACKWELL, MOBSTER KIDS PRODUCERS “We love InkTip. -

21 05/03/2014 ...And Justice for All 19/10/1979 #Followfriday 15/09/2016

21 05/03/2014 ...And Justice for All 19/10/1979 #Followfriday 15/09/2016 $ (Dollars) (The Heist) 15/12/1971 10 Rillington Place 12/05/1971 1001 Arabian Nights 01/12/1959 12 To The Moon 22/06/1960 13 Frightened Girls 01/07/1963 13 Frightened Girls (The Candy Web) 01/07/1963 13 Ghosts (1960) 01/07/1960 13 Going On 30 01/01/2005 13 West Street 01/05/1962 1776 11/08/1972 17th Precinct 30/12/2011 19th Wife 13/09/2010 2 Guns 01/02/2014 20 Million Miles To Earth 01/07/1957 20/30/40 11/03/2004 2012 11/11/2009 21 (2008) 27/03/2008 21 Jump Street 01/10/2012 22 Jump Street 05/06/2014 28 Days 14/04/2000 29 Acacia Avenue 01/05/1945 3 Ninjas: High Noon At Mega Mountain 10/04/1998 3:10 to Yuma 07/08/1957 30 Is A Dangerous Age, Cynthia 01/04/1968 30 Minutes Or Less 10/08/2011 40 Carats 28/06/1973 40 Guns To Apache Pass 01/05/1967 5 Against The House 10/06/1955 50 First Dates 12/02/2004 50 To 1 21/03/2014 7 Seconds 22/09/2004 711 Ocean Drive 20/07/1950 7th Cavalry 07/12/1956 84 Charing Cross Road 13/02/1987 8MM 26/02/1999 8MM 2 15/02/2005 919 Fifth Avenue 01/01/1995 976-Evil 24/03/1989 A Bullet Is Waiting 04/09/1954 A Child Lost Forever 16/11/1992 A Close Call For Boston Blackie 24/01/1946 A Dandy In Aspic (1968) 02/04/1968 A Dangerous Adventure 22/07/1937 A Dangerous Affair 30/09/1931 A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg 04/06/1972 A Doctor's Story 23/04/1984 A Dogs Way Home 09/04/19 A Feather In Her Hat 25/10/1933 A Fight To The Finish (1937) 30/06/1937 A Fine Mess 08/08/1986 A Fire In The Sky (1978) 26/11/1978 A Girl Like Me: The Gwen Araujo Story 19/06/2006