The Case for Renewal in Post-Secondary Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Election New Democratic Party of Ontario Candidates

2018 Election New Democratic Party of Ontario Candidates NAME RIDING CONTACT INFORMATION Monique Hughes Ajax [email protected] Michael Mantha Algoma-Manitoulin [email protected] Pekka Reinio Barrie-Innisfil [email protected] Dan Janssen Barrie-Springwater-Ono- [email protected] Medonte Joanne Belanger Bay of Quinte [email protected] Rima Berns-McGown Beaches-East York [email protected] Sara Singh Brampton Centre [email protected] Gurratan Singh Brampton East [email protected] Jagroop Singh Brampton West [email protected] Alex Felsky Brantford-Brant [email protected] Karen Gventer Bruce-Grey-Owen Sound [email protected] Andrew Drummond Burlington [email protected] Marjorie Knight Cambridge [email protected] Jordan McGrail Chatham-Kent-Leamington [email protected] Marit Stiles Davenport [email protected] Khalid Ahmed Don Valley East [email protected] Akil Sadikali Don Valley North [email protected] Joel Usher Durham [email protected] Robyn Vilde Eglinton-Lawrence [email protected] Amanda Stratton Elgin-Middlesex-London [email protected] NAME RIDING CONTACT INFORMATION Taras Natyshak Essex [email protected] Mahamud Amin Etobicoke North [email protected] Phil Trotter Etobicoke-Lakeshore [email protected] Agnieszka Mylnarz Guelph [email protected] Zac Miller Haliburton-Kawartha lakes- [email protected] -

“Doug Ford Has Been Ducking Work and Ducking Accountability.”

Queen’s Park Today – Daily Report March 11, 2019 Quotation of the day “Doug Ford has been ducking work and ducking accountability.” NDP MPP Catherine Fife criticizes the premier for being MIA in question period more than half of the time since December. Today at Queen’s Park On the schedule MPPs are in their ridings for the March Break constituency week. The House is adjourned until Monday, March 18. Premier watch This weekend Premier Doug Ford hit up a youth-focused roundtable discussion with Mississauga-Malton MPP Deepak Anand and visited IBM Canada’s headquarters in Markham. Ford trumpeted his government’s work to make Ontario “open for business” and “life more affordable for university and college students” on his social media feeds. But NDP MPP Catherine Fife says the premier has been “ducking work and ducking accountability” over the Ron Taverner controversy, pointing out Ford was MIA for 11 of 18 question periods since December. Meanwhile the premier’s office points out official Opposition Leader Andrea Horwath has skipped out on question period in about equal proportion over the last session. Global News breaks down the details. Hydro One executive salary will be capped at $1.5M Ontario’s PC government has won a standoff with Hydro One over executive pay. The provincial utility said Friday it agreed to cap its next boss’ direct compensation at $1.5 million, which includes a $500,000 base salary and up to $1 million in bonuses for hitting certain short- and long-term benchmarks. The salaries of other board members will be limited to 75 per cent of what the next CEO rakes in. -

GLP WEEKLY Issue 13

April 17, PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM Volume 14, 2020 GLP WEEKLY Issue 13 PEO OTTAWA CHAPTER GLP CHAIR SPEAKS WITH NDP LEADER PEO Ottawa Chapter GLP Chair and former Councillor Ishwar Bhatia, P.Eng., (right) had the chance to speak with NDP Leader Andrea Horwath, MPP (Hamilton Centre) (left) at an MPP event in Ottawa on February 27. This event happened prior to the government shutdown, but we recently received this story for the GLP Weekly. For more on this story, see page 6. Through the Professional Engineers Act, PEO governs over 89,000 licence and certificate holders, and regulates and advances engineering practice in Ontario to protect the public interest. Professional engineering safeguards life, health, property, economic interests, the public welfare and the environment. Past issues are available on the PEO Government Liaison Program (GLP) website at https://www.peo.on.ca/index.php/about-peo/glp-weekly- newsletter Deadline for submissions is the Thursday of the week prior to publication. The next issue will be published on April 24, 2020. 1 | PAGE TOP STORIES THIS WEEK 1. PEO PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS COMMITTEE RELEASES STRUCTURE GUIDELINES 2. PEO OAKVILLE CHAPTER HELD DISCUSSION WITH MINISTER 3. MINISTER, MPP AND PARTY LEADER HOST ONLINE TOWN HALLS 4. PEO ISSUES PRACTICE ADVISORY NOTICE FOR ESSENTIAL WORKERS PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM (GLP) Although we cannot attend in—person events, there are other opportunities to connect with MPPs virtually. MPPs are still receiving and sending emails, taking calls, conducting meetings remotely, and happy to connect. GLP subscribers are encouraged to keep a look out for upcoming townhalls, participate, and share what you learned with the GLP. -

The Great Skills Divide: a Review of the Literature

The Great Skills Divide: A Review of the Literature Sophie Borwein Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario Published by The Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario 1 Yonge Street, Suite 2402 Toronto, ON Canada, M5E 1E5 Phone: (416) 212-3893 Fax: (416) 212-3899 Web: www.heqco.ca E-mail: [email protected] Cite this publication in the following format: Borwein, S. (2014). The Great Skills Divide: A Review of the Literature. Toronto: Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. The opinions expressed in this research document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or official policies of the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario or other agencies or organizations that may have provided support, financial or otherwise, for this project. © Queens Printer for Ontario, 2014 The Great Skills Divide: A Review of the Literature Executive Summary Discussions of Canada’s so-called “skills gap” have reached a fever pitch. Driven by conflicting reports and data, the conversation shows no signs of abating. On the one hand, economic indicators commonly used to identify gaps point to problems limited to only certain occupations (like health occupations) and certain provinces (like Alberta) rather than to a general skills crisis. On the other hand, employers continue to report a mismatch between the skills they need in their workplaces and those possessed by job seekers, and to voice concern that the postsecondary system is not graduating students with the skills they need. This paper is the first of three on Canada’s skills gap. It outlines the conflicting views around the existence and extent of a divide between the skills postsecondary graduate possess and those employers want. -

Recasting Federal Workforce Development Programs Under the Harper Government

Hollowing out the middle Recasting federal workforce development programs under the Harper government Donna E. Wood1 All developed countries invest in workforce development. These are measures designed to attract and retain talent, solve skills deficiencies, improve the quality of the workplace, and enhance the competitiveness of local firms. They are also meant to incorporate the disadvantaged, integrate immigrants, and help the unemployed find work. Government intervention is necessary to improve market efficiency, pro- mote equal opportunity, and ensure social and geographic mobility among citizens. As a domain that straddles both social and economic policy, workforce develop- ment is particularly complicated in Canada. This is because our Constitution is am- biguous on whether this is an area of federal or provincial responsibility. Most pro- grams, like postsecondary education and apprenticeship, are clearly under provincial control, but there is less certainty around measures to help the unemployed. Before the Second World War, it was accepted that these kinds of programs were under provincial responsibility. Often the federal government helped financially. After the devastation of the Depression in the 1930s, the federal government and all the provinces agreed, in 1940, to a constitutional amendment transferring significant responsibilities to Ottawa through a national unemployment insurance program. By the 1990s, Ottawa dominated the policy area through a network of about 500 Canada Employment Centres across the country, delivering both income sup- The Harper Record 2008–2015 | Labour and Migration 183 port and employment services. In 1996, the federal Liberal government offered to transfer responsibility for employment services back to the provinces.2 Ottawa kept responsibility for income support. -

National Media Coverage of Higher Education in Canada

What’s the Story? National Media Coverage of Higher Education in Canada Tanya Whyte, Kaspar Beelen, Alex Mierke-Zatwarnicki, Christopher Cochrane, Peter Loewen, University of Toronto, Scarborough Published by The Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario 1 Yonge Street, Suite 2402 Toronto, ON Canada, M5E 1E5 Phone: (416) 212-3893 Fax: (416) 212-3899 Web: www.heqco.ca E-mail: [email protected] Cite this publication in the following format: Whyte, T., Beelen, K., Mierke-Zatwarnicki, A., Cochrane, C., Loewen, P. (2016) What’s the Story? National Media Coverage of Higher Education in Canada. Toronto: Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. The opinions expressed in this research document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or official policies of the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario or other agencies or organizations that may have provided support, financial or otherwise, for this project. © Queens Printer for Ontario, 2016 What’s the Story? National Media Coverage of Higher Education in Canada Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................5 Research Question ........................................................................................................................................5 Methodology -

STEM Skills and Canada's Economic Productivity

SOME AssEMBLY REQUIRED: STEM SKILLS AND CANADA’S ECONOMIC PRODUctIVITY The Expert Panel on STEM Skills for the Future Science Advice in the Public Interest SOME ASSEMBLY REQUIRED: STEM SKILLS AND CANADA’S ECONOMIC PRODUCTIVITY The Expert Panel on STEM Skills for the Future ii Some Assembly Required: STEM Skills and Canada’s Economic Productivity THE COUNCIL OF CANADIAN ACADEMIES 180 Elgin Street, Suite 1401, Ottawa, ON, Canada K2P 2K3 Notice: The project that is the subject of this report was undertaken with the approval of the Board of Governors of the Council of Canadian Academies. Board members are drawn from the Royal Society of Canada (RSC), the Canadian Academy of Engineering (CAE), and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS), as well as from the general public. The members of the expert panel responsible for the report were selected by the Council for their special competencies and with regard for appropriate balance. This report was prepared for the Government of Canada in response to a request from the Minister of Employment and Social Development Canada. Any opinions, findings, or conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors, the Expert Panel on STEM Skills for the Future, and do not necessarily represent the views of their organizations of affiliation or employment. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Some assembly required : STEM skills and Canada’s economic productivity / the Expert Panel on STEM Skills for the Future. Includes bibliographical references. Electronic monograph in PDF format. ISBN 978-1-926522-09-8 (pdf) 1. Economic development – Effect of education on – Canada. -

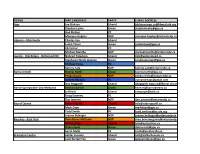

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY E-MAIL ADDRESS Ajax Joe

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY E-MAIL ADDRESS Ajax Joe Dickson Liberal [email protected] Stephen Leahy Green [email protected] Rod Phillips PC Monique Hughes NDP [email protected] Algoma—Manitoulin Charles Fox Liberal Justin Tilson Green [email protected] Jib Turner PC Michael Mantha NDP [email protected] Aurora - Oak Ridges - Richmond Hill Naheed Yaqubian Liberal [email protected] Stephanie Nicole Duncan Green [email protected] Michael Parsa PC Katrina Sale NDP [email protected] Barrie-Innisfil Bonnie North Green [email protected] Pekka Reinio NDP [email protected] Andrea Khanjin PC [email protected] Ann Hoggarth Liberal [email protected] Barrie-Springwater-Oro-Medonte Keenan Aylwin Green [email protected] Jeff Kerk Liberal [email protected] Doug Downey PC Dan Janssen NDP [email protected] Bay of Quinte Robert Quaiff Liberal [email protected] Mark Daye Green [email protected] Todd Smith PC [email protected] Joanne Belanger NDP [email protected] Beaches—East York Rima Berns-McGown NDP [email protected] Arthur Potts Liberal [email protected] Debra Scott Green [email protected] Sarah Mallo PC [email protected] Brampton Centre Safdar Hussain Liberal [email protected] Laila Zarrabi Yan Green [email protected] Harjit Jaswal PC [email protected] Sara Singh NDP [email protected] Brampton East Dr. Parminder Singh Liberal [email protected] Raquel Fronte Green [email protected] Sudeep Verma PC Gurratan -

Alternate REVP Report – Rapport Du VPER Suppléant January 1St – April 30Th 2019 Prepared April 29Th Report by Alex Silas, A/REVP PSAC-NCR

Alternate REVP Report – Rapport du VPER Suppléant January 1st – April 30th 2019 Prepared April 29th Report by Alex Silas, A/REVP PSAC-NCR Since my election as Alternate REVP in December I’ve endeavoured to hit the ground running and be a strong presence & voice for members of the NCR. As your A/REVP I’ve been an active participant & organizer for Treasury Board Bargaining Mobilizing and we remain active in our fight against Phoenix to put pressure on the government to fix its broken pay system. I’ve continued my involvement in our “Heat Is On” Campaign and we have made headway fighting privatization in the NCR. I’ve focused on engaging Young Workers in our union and have been active in our YWC which has grown not only in membership but in activism. I’ve continued to work towards engaging DCL members and creating a network of NCR-DCL locals. I’ve also remained on-hand and at the disposal of our equity & action committees and have strived to be an ally to promote and support diversity & equity in our union. I’ve taken part in lobbying of elected officials on both local & national campaigns for the public service and the broader labour & progressive movement and have provided testimonial & media interviews as an elected union official. I’ve prioritized advancing my union education to further develop my skillset & knowledge-base as a labour activist. I’ve sought to build links inter-regionally and across our union’s components to work together to face common challenges. I’ve organized & rallied with aligned labour & community organizations seeking to strengthen the bonds of solidarity within our movement, with a priority on community involvement with the intent that solidarity means community. -

Funding for Expansion, We Have Outlined Some Options That Can Help You Get Back to Business

Helping you get back to business Project-based incentives and grant programs The COVID-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on Canadian businesses and the global economy as a whole. As businesses prepare to re-open their doors, they will continue to need access to support and funds to fuel their recovery. To help, both the federal and provincial governments are offering a range of new and existing programs to support project-based initiatives. From research and development grants to direct funding for expansion, we have outlined some options that can help you get back to business. Programs Federal Grants Provincial Grants Supercluster Grants PIC Co-Investment Sustainable Development Innovate BC Funding Program Technology Canada (SDTC) Alberta Innovates Scale AI Co-Investment Strategic Innovation Fund (SIF) Alberta Relaunch Grant Funding Program Futurpreneur Canada Creative Saskatchewan Accelerated Ocean Financing Program Ontario Development Funds Solutions Program Industrial Research Assistance Program (IRAP) Ontario Interactive Digital Media Fund Youth Employment and Youth Employment Green Program Ontario Automotive Modernization Program CanExport Program Atlantic Innovation Fund (AIF) Career Ready Program Canada Job Grant (CJG) Tax Credits Career Launcher Internships Regional Relief and Recovery Fund Digital Media Tax Credit Ontario Regional Opportunities Tax Credit Scientific Research & Experimental Development (SR&ED) Film & Video Production Tax Credits (CPTC) Federal Grant programs GOVERNMENT OF CANADA Sustainable Development Technology Canada (SDTC) Purpose Who should apply? To assist Canadian small and medium-sized Businesses developing new and novel technology businesses advancing innovative pre-commercial with significant and quantifiable environmental technologies that have the potential to have benefit to Canada: environmental and economic benefits for climate • Who have formed a consortium that includes at least change, clean air, clean water and clean soil. -

Mpps Relative to Post COVID Economic Revival – Long Term Care & Child Care Feb

MPPs relative to Post COVID Economic Revival – Long Term Care & Child Care Feb. 2, 2021 https://www.ola.org/en/members/current/composite-list https://www.ola.org/en/members/current NAME POSITION RIDING EMAIL CONSERVATIVE Hon. Doug Ford Premier Etobicoke https://correspondence.premier.gov .on.ca/EN/feedback/default.aspx Will Bouma Parliamentary Assistant to Brantford-Brant [email protected] the Premier Hon. Christine Deputy Premier and Newmarket-Aurora [email protected] Elliott Minister of Health Robin Martin Parliament Secretary to Eglington- [email protected] the Minister of Health Lawrence Hon. Merrilee Minister of Long-Term Kanata-Carleton [email protected] Fullerton Care Effie J. Parliament Secretary to Oakville North - [email protected] Triantafilopoulos the Minister of Long-Term Burlington Care Hon. Raymond Minister for Seniors and Scarborough North [email protected] Sung Joon Cho Accessibility Daisy Wai Parliament Secretary to Richmond Hill [email protected] the Minister for Seniors and Accessibility Hon. Peter Minister of Finance Pickering-Uxbridge [email protected] Bethlenfalvy Stan Cho Parliamentary Assistant to Willowdale [email protected] the Minister of Finance Hon. Stephen Minister of Education King-Vaughan [email protected] Lecce Sam Oosterhoff Parliamentary Assistant to Niagara West [email protected] the Minister of Education Hon. Jill Dunlop Associate Minister of Simcoe North [email protected] Children and Women’s Issues Hon. Todd Smith Minister of Children, Bay of Quinte [email protected] Community and Social Service Jeremy Roberts Parliamentary Assistant to Ottawa West- [email protected] the Minister of Children, Nepean Community and Social Service (Community and Social Services) Hon. -

Community Health and a New Government What to Expect WELCOME and OPENING REMARKS KAREN PARSONS & RAYMOND APPLEBAUM Meeting Objectives

Community Health and A New Government What to Expect WELCOME AND OPENING REMARKS KAREN PARSONS & RAYMOND APPLEBAUM Meeting Objectives • Information on key topics for Agencies • Generate ideas you can take to support your agency • Generate ideas we work on together • Connect with people Meeting Agenda Activity Speakers Time Metamorphosis Strategic Plan Jerry Mings & 2:15 Raymond Applebaum M‐SAA’s 2019 to 2022 Update Patrick Boily 2:35 an CSS/ MH&A Base Funding Raymond Applebaum & 2:55 Patrick Boily Break 3:15 Round Table Conversation All 3:30 a) Working Together to Support Clients b) Working Together to Navigate Pending System Changes c) Potential Questions for the Panel Closing Remarks Raymond Applebaum & 4:50 Karen Parsons Meeting Agenda Activity Speakers Time Dinner All 5:00 Welcome and Opening Raymond Applebaum & 5:45 Remarks Karen Parsons an Insights from the Afternoon Participants 6:00 Inside the New Government Santis Health Team 6:15 Dan Carbin, Principal Inside the Changing Panel 7:15 Environment Deborah Simon – OSCA Barney Savage – AMHO Camille Quenneville – CMHA ‐ Ontario Closing Remarks Raymond Applebaum & 8:15 Karen Parsons End of Meeting All 8:30 Process for the Session Small Table Questions of Presentations Conversation Clarity Notes that Insights may help this evening http://sli.do Event Code ‐ #U346 Everyone will Everyone has hear others wisdom and be heard Working We need The whole is Assumptions everyone’s greater than wisdom for the sum of the wisest the parts results There are no wrong answers Let’s get started Strategic Plan 2018 ‐2023 Special Thanks to Region of Peel We wish to acknowledge the Region of Peel Human Services Department for their generous support and committed funding to the Organizational Effectiveness Fund.