The Development and Location of Industries in Greater Cape Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stories of the South Peninsula

Stories of the South Peninsula Historical research, stories and heritage tourism opportunities in the South Peninsula AFRICANSOUTH TOURISM The peninsula from Cape Point Nature Reserve Prepared for the City of Cape Town by C. Postlethwayt, M. Attwell & K. Dugmore Ström June 2014 Making progress possible. Together. Background The primary objective of this project was to prepare a series of ‘story packages’ providing the content for historical interpretive stories of the ‘far’ South Peninsula. Stories cover the geographical area of Chapman’s Peak southwards to include Imhoff, Ocean View, Masiphumelele, Kommetjie, Witsand, Misty Cliffs and Scarborough, Plateau Road, Cape Point, Smitswinkel Bay to Miller’s Point, Boulders, Simon’s Town, Red Hill, Glencairn and Fish Hoek to Muizenberg. The purposes for which these stories are to be told are threefold, namely to support tourism development; to stimulate local interest; and to promote appropriate and sustainable protection of heritage resources through education, stimulation of interest and appropriate knowledge. To this end, the linking of historical stories and tourism development requires an approach to story-telling that goes beyond the mere recording of historic events. The use of accessible language has been a focus. Moreover, it requires an approach that both recognises the iconic, picture-postcard image of parts of Cape Town (to which tourists are drawn initially), but extends it further to address the particular genius loci that is Cape Town’s ‘Deep South’, in all its complexity and coloured by memory, ambivalences and contradictory experiences. We believe there is a need to balance the more conventional approach, which selects people or events deemed worthy of commemoration (for example, the Battle of Muizenberg) to tell the story of places, by interweaving popular memory and culture into these recordings (for example, the rich Muslim culture that existed in Simon’s Town before the removal under the Group Areas Act). -

It Is Not About The

MyCiTi Bus Service Film Industry Pre-Season Briefing Ronald Kingma Manager IRT Operations Kobus Swanepoel Client Services Transport for Cape Town 11 October 2013 Contents 1. Current System 2. Future Expansion 3. Key Principles 4. Procedure for Filming 5. CCT Fare Policy 6. Application Forms 7. Application Procedure Summary 8. Past film events Current System • Buses : 270 buses • Trunk Routes : Route T01 Wood station – Civic Centre : Route T01a Wood station – V&A Waterfront : Route A01 Airport – V&A Waterfront • Feeder Routes : Route 101 Civic Centre - Gardens : Route 102 Civic Centre – Walmer Estate – Salt River : Route 213 West Beach – Table View - Sunningdale : Route 214 Big Bay – Table View – Parklands : Route 215 Sunningdale- Gie Road - Wood station : Route 216 Sunningdale – Wood Drive – Wood station • Trunk Stations : 17 on Table View, 1 Airport and 4 on Inner City Feeder • Feeder Stops : Inner City: 35 stops : Table View: Over 100 stops • Daily Passengers : 9,000 - 12,000 on weekdays : 2,000 - 5,000 on weekend days • Operation : Approximately 18 hrs per day Future Expansion • 1 November Routes : Route 101 Vredehoek – Gardens - Civic Centre : Route 103 Oranjezicht – Gardens – Civic Centre : Route 104 Sea Point – Waterfront – Civic Centre : Route 105 Sea Point – Fresnaye – Civic Centre : Route 217 Table View - Melkbosstrand : Route 230 Melkbosstrand - Duinefontein • November /Dec : Route 106 Waterfront Silo – Civic Centre – Camps Bay (Clockwise) : Route 107 Waterfront Silo – Civic Centre – Camps Bay (Anti - Clockwise) : Route 251 -

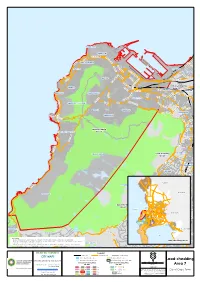

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Cape Town's Failure to Redistribute Land

CITY LEASES CAPE TOWN’S FAILURE TO REDISTRIBUTE LAND This report focuses on one particular problem - leased land It is clear that in order to meet these obligations and transform and narrow interpretations of legislation are used to block the owned by the City of Cape Town which should be prioritised for our cities and our society, dense affordable housing must be built disposal of land below market rate. Capacity in the City is limited redistribution but instead is used in an inefficient, exclusive and on well-located public land close to infrastructure, services, and or non-existent and planned projects take many years to move unsustainable manner. How is this possible? Who is managing our opportunities. from feasibility to bricks in the ground. land and what is blocking its release? How can we change this and what is possible if we do? Despite this, most of the remaining well-located public land No wonder, in Cape Town, so little affordable housing has been owned by the City, Province, and National Government in Cape built in well-located areas like the inner city and surrounds since Hundreds of thousands of families in Cape Town are struggling Town continues to be captured by a wealthy minority, lies empty, the end of apartheid. It is time to review how the City of Cape to access land and decent affordable housing. The Constitution is or is underused given its potential. Town manages our public land and stop the renewal of bad leases. clear that the right to housing must be realised and that land must be redistributed on an equitable basis. -

Cape Town Tygerberg Football Association

Cape Town Tygerberg Football Association Life Members Chairman Vice Chairman Secretary C PANDIT 1991 E DALTON 1993-2004 D WHITING 1993-1997 L MacKAY 1993-1996 D D'OLIVIERA 1991 D TULLEKEN 2005-2009 L RUNDLE 1998-2002 N TOWNSEND 1997- G TAMBAY 1991 A BOTHMAN 2010 B JOHNSON 2003-2004 J ROMAN 1991 P JACOBS 2005 E DALTON 1996 T MORGAN 2006-2007 D ESSACK D ROMAN 2008 D WHITING 1997 R ANTHONY 2010- L RUNDLE 2002 T MORGAN 2007 Chairmans Award Club of the Year Team of the Year Fair Play Trophey T.M.T. Trophey Albert Richardson Vets Player 1992 D ESSACK 1993 T BREVIS 1994 G CRUMPTON TRAMWAY 1995 D WHITING GARDENVILLAGE DEFENCE 1996 E vd MERWE AVENDALE ATH VASCO da GAMA 1997 D TULLEKEN EDGEMEAD G/W NORTHPINE UTD FN RANGERS FISH HOEK TRAMWAY 1998 D TULLEKEN MUTUAL UTD HELLENIC (colts) BELLVILLE CITY CLYDE PINELANDS BELLVILLE CITY 1999 L RUNDLE OLD MUTUAL CAMPS BAY CLYDE PINELANDS ANA GONCALVES FC FORTUNE Ian LEWIS 2000 A DYAMOND SAXON ROVERS EDGEMEAD G/W FISH HOEK TABLE VIEW SAXON ROVERS Danny SMYTH 2001 G CRUMPTON EDGEMEAD G/W VASCO da GAMA DE BEERS CAMPS BAY AVENDALE ATH Pepe dos SANTOS 2002 A DYAMOND EDGEMEAD G/W AJAX CAPE TOWN FISH HOEK NORWAY PARKS FC FORTUNE Eric KEET 2003 A DYAMOND BELLVILLE CITY EDGEMEAD G/W MEADOWRIDGE BELLVILLE CITY VASCO da GAMA Gareth JEENES 2004 L MILNE DURBANVILLE FN RANGERS FN RANGERS FN RANGERS VASCO da GAMA Mike KALLIS 2005 A GONCALVES RYGERSDAL RYGERSDAL WYNBERG st JOHNS OLD MUTUAL TABLE VIEW Kenny GERTSE 2006 L HAMBURGER GARDENVILLAGE DURBANVILLE NORTPINE UNITED BELLVILLE CITY OLD MUTUAL Leslie KALLIS 2007 DURBANVILLE -

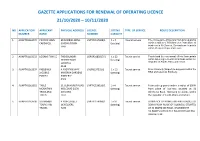

Gazette Applications for Renewal of Operating Licence 21/10/2020 – 10/11/2020

GAZETTE APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL OF OPERATING LICENCE 21/10/2020 – 10/11/2020 NO APPLICATION APPLICANT PHYSICAL ADDRESS LICENCE SITTING TYPE OF SERVICE ROUTE DESCRIPTION NUMBER NAME NUMBER CAPACITY 1. AONPTR1163497 PATRICK JOHN 88 DORRIES DRIVE LNPTR1157888/1 1 x 4 Tourist service The conveyance of tourists from pick up points CARDWELL SIMONS TOWN (seating) within a radius of 60 kilometres from place of 7995 business in 88 Dorries, Simonstown to points within Western Cape and return. 2. AONPTR1163532 LOGANS TAXI CC THE BOUNDRY LGPGP0183817/1 1 x 22 Tourist service Tourist and their personal effects from points DENNIS ROAD (seating) within Gauteng to tourist attractions within the LONEHILL Republic of South Africa and return. 2128 3. AONPTR1163537 FREDERICK 4 AVENTINE WAY LNCPB237532/3 1 x 13 Tourist service From Kimberly (Airport) to any point within the JACOBUS MINERVA GARDENS (seating) RSA and return to Kimberly. POWELL KIMBERLY 8301 4. AONPTR1163552 TABLE 31 GLENHURST ROAD LNPTR1158193/1 1 x 4 Tourist service From pick up points within a radius of 35KM MOUNTAIN WELCOME GLEN (seating) from place of business situated at 31 TREKS AND ATHLONE Glenhurst Road, Glencairn to points within TOURS 7975 the Republic of South Africa and return. 5. AONPTR1163530 SISINAMBO 4 YORK STREET LNPTR1159090/1 1 x 10 Tourist service FROM PICK UP POINTS WITHIN A RADIUS OF TOURS AND DE KELDERS (seating) 35KM FROM PLACE OF BUSINESS SITUATED TRAVEL 7220 AT 35 MARMION ROAD, ORANJEZICHT TO POINTS WITHIN THE BOUNDRIES OF RSA AND RETURN GAZETTE APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL OF OPERATING LICENCE 21/10/2020 – 10/11/2020 6. -

AC097 FA Cape Town City Map.Indd

MAMRE 0 1 2 3 4 5 10 km PELLA ATLANTIS WITSAND R27 PHILADELPHIA R302 R304 KOEBERG R304 I CAME FOR DUYNEFONTEIN MAP R45 BEAUTIFULR312 M19 N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 LANDSCAPES,PAARL M14 R304 R302 R27 M58 AND I FOUND Blaauwberg BEAUTIFULN1 PEOPLE Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND M48 B6 ROBBEN ISLAND PARKLANDS R302 KLAPMUTS TABLE VIEW M13 JOOSTENBERG KILLARNEY DURBANVILLE VLAKTE City Centre GARDENS KRAAIFONTEIN N1 R44 Atlantic Seaboard Northern Suburbs SONSTRAAL M5 N7 Table Bay Sunset Beach R304 Peninsula R27 BOTHASIG KENRIDGE R101 M14 PLATTEKLOOF M15 Southern Suburbs M25 EDGEMEAD TYGER VALLEY MILNERTON SCOTTSDENE M16 M23 Cape Flats M8 BRACKENFELL Milnerton Lagoon N1 Mouille Point Granger Bay M5 Helderberg GREEN POINT ACACIA M25 BELLVILLE B6 WATERFRONT PARK GOODWOOD R304 Three Anchor Bay N1 R102 CAPE TOWN M7 PAROW M23 Northern Suburbs STADIUM PAARDEN KAYAMANDI SEA POINT EILAND R102 M12 MAITLAND RAVENSMEAD Blaauwberg Bantry Bay SALT RIVER M16 M16 ELSIESRIVIER CLIFTON OBSERVATORY M17 EPPING M10 City Centre KUILS RIVER STELLENBOSCH Clifton Bay LANGA INDUSTRIA M52 Cape Town Tourism RHODES R102 CAMPS BAY MEMORIAL BONTEHEUWEL MODDERDAM Visitor Information Centres MOWBRAY N2 R300 M62 B6 CABLE WAY ATHLONE BISHOP LAVIS M12 M12 M3 STADIUM CAPE TOWN TABLE MOUNTAIN M5 M22 INTERNATIONAL Police Station TABLE RONDEBOSCH ATHLONE AIRPORT BAKOVEN MOUNTAIN NATIONAL BELGRAVIA Koeël Bay PARK B6 NEWLANDS RYLANDS Hospital M4 CLAREMONT GUGULETU DELFT KIRSTENBOSCH M54 R310 Atlantic Seaboard BLUE DOWNS JAMESTOWN B6 Cape Town’s Big 6 M24 HANOVER NYANGA Oude Kraal KENILWORTH PARK -

Cape Town 2021 Touring

CAPE TOWN 2021 TOURING Go Your Way Touring 2 Pre-Booked Private Touring Peninsula Tour 3 Peninsula Tour with Sea Kayaking 13 Winelands Tour 4 Cape Canopy Tour 13 Hiking Table Mountain Park 14 Suggested Touring (Flexi) Connoisseur's Winelands 15 City, Table Mountain & Kirstenbosch 5 Cycling in the Winelands & visit to Franschhoek 15 Cultural Tour - Robben Island & Kayalicha Township 6 Fynbos Trail Tour 16 Jewish Cultural & Table Mountain 7 Robben Island Tour 16 Constantia Winelands 7 Cape Malay Cultural Cooking Experience 17 Grand Slam Peninsula & Winelands 8 “Cape Town Eats” City Walking Tour 17 West Coast Tour 8 Cultural Exploration with Uthando 18 Hermanus Tour 9 Cape Grace Art & Antique Tour 18 Shopping & Markets 9 Group Scheduled Tours Whale Watching & Shark Diving Tours Group Peninsula Tour 19 Dyer Island 'Big 5' Boat Ride incl. Whale Watching 10 Group Winelands Tour 19 Gansbaai Shark Diving Tour 11 Group City Tour 19 False Bay Shark Eco Charter 12 Touring with Families Family Peninsula Tour 20 Family Fun with Animals 20 Featured Specialist Guides 21 Cape Town Touring Trip Reports 24 1 GO YOUR WAY – FULL DAY OR HALF DAY We recommend our “Go Your Way” touring with a private guide and vehicle and then customizing your day using the suggested tour ideas. Cape Town is one of Africa’s most beautiful cities! Explore all that it offers with your own personalized adventure with amazing value that allows a day of touring to be more flexible. RATES FOR FULL DAY or HALF DAY– GO YOUR WAY Enjoy the use of a vehicle and guide either for a half day or a full day to take you where and when you want to go. -

Groundwater a Source of Water for the Deep South

GROUNDWATER A SOURCE OF WATER FOR THE DEEP SOUTH Roger Parsons 1, John Coetzee 2 and Chris Wise 2 1Parsons and Associates Specialist Groundwater Consultants, PO Box 2606 Somerset West 7129. Tel (021) 855-2480. E-mail: [email protected] 2Jeffares and Green (Pty) Ltd ABSTRACT Adequate supply of water to the southern suburbs of Cape Town, including Fish Hoek, Simon’s Town and Noordhoek, is increasingly coming under threat as these suburbs expand and their demand for water increases. Upgrading and expanding existing water reticulation pipelines through Muizenberg to these areas is possible, but will be expensive and disruptive. Alternative sources of water were hence considered, including the construction of a dam at Brooklands above Simon’s Town and development of local groundwater resources. This paper describes the potential for developing groundwater resources to increase a secure supply of water to these areas. INTRODUCTION The area south of Clovelly – including Fish Hoek, Noordhoek, Simon’s Town, Scarborough and Kommetjie – currently obtains water from water resources above Simon’s Town (Lewis-Gay Dam, Kleinplaas Dam, and Rawson Dam) and via a pipeline running through Muizenberg and Kalk Bay. A dam site at Brooklands was identified some 30 years ago as a potential future source of water to augment existing supplies (Figure 1). In response to a land claim – parts of which would be flooded should the dam be built - the City of Cape Town investigated whether the Brooklands Dam site was still required. To be able to make an informed decision regarding the reservation of the land for construction of the Brooklands Dam at some point in the future, the City of Cape Town commissioned a study to investigate water resource and supply options for the area colloquially referred to as the Deep South. -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

Cape Town Rd R L N W Or T

Legend yS Radisson SAS 4 C.P.U.T. u# D S (Granger Bay Campus) H R u Non-Perennial River r Freeway / National Road R C P A r E !z E l e T Mouille Point o B . Granger Bay ast y A t Perennial River h B P l Village E Yacht Club e Through Route &v e A d ie x u# s Granger r a Ü C R P M R a H nt n d H . r l . R y hN a e d y d u# Ba G Bay L i % Railway with Station r R ra r P E P The Table Minor Road a D n te st a Table Bay Harbour l g a a 7 La Splendina . e s N R r B w Bay E y t ay MetropolitanO a ak a P Water 24 R110 Route Markers K han W y re u i n1 à î d ie J Step Rd B r: u# e R w Q r ie Kings Victoria J Park / Sports Ground y t W 8} e a L GREEN POINT Wharf 6 tt B a. Fort Wynyard Warehouse y y Victoria Built-up Area H St BMW a E K J Green Point STADIUM r 2 Retail Area Uà ge Theatre Pavillion r: 5 u lb Rd an y Q Basin o K Common Gr @ The |5 J w Industrial Area Pavillion!C Waterfront ua e Service Station B Greenpoint tt çc i F Green Point ~; Q y V & A WATERFRONT Three Anchor Bay ll F r: d P ri o /z 1 R /z Hospital / Clinic with Casualty e t r CHC Red Shed ÑG t z t MARINA m u# Hotel e H d S Cape W Somerset Quay 4 r r y Craft A s R o n 1x D i 8} n y th z Hospital / Clinic le n Medical a Hospital Warehouse u 0 r r ty m Green Point Club . -

Things to Do in Cape Town NUMBER 1: Robben Island

Things to Do in Cape Town NUMBER 1: Robben Island Price: adult (R250); children under 18 (R120) The standard tour to Robben Island is 3.5 hours long, including the two half-hour ferry rides. Ferries depart at 9am, 11am, 1pm and 3pm everyday (weather permitting) from the V & A Waterfront in Cape Town. The summer season is very busy and we recommend you book early to avoid disappointment! Booking a minimum of three days in advance is recommended. To book tickets: Website: www.robben-island.org.za Call: 021 413 4220/1 (Robben Island Museum); 021 413 4233 / 37 (Advanced Booking) Email: [email protected] The ticket sales office is located at the Nelson Mandela Gateway at the V&A Waterfront, Cape Town. Once you have completed your trip, you may wish to indulge in a bit of shopping or have a relaxing lunch at one of the many restaurants situated at the Waterfront on the harbour. NUMBER 2: Table Mountain Price: Cable car (Return and one way tickets available) Adult: Return: R205 Children (4 – 17 years): Return: R100 Children (Under 4): Free Sunset special: For the month of January, return tickets after 18h00 will be half price and can be bought only from the ticket office at the Lower Cable Station after 18h00. One can either cable car or walk up to reach the top of the mountain. The cable car goes up every 15 minutes, so you don’t need to worry about catching one. However you will need to take note of the weather.