Toward an Environmental Conservatism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texas Conservative Grassroots Coalition Letter

November 18, 2020 Dear Texas House Republicans, Once again Democrat efforts to turn Texas blue were soundly rejected by voters across the Lone Star State. While we continue to wait for election results to settle here in Texas and across the nation, it is obvious that Texas voters have delivered a mandate for conservative reform to their elected officials. While our control over national affairs is limited, Republican control of Texas is absolute. The GOP holds majorities in both chambers of the Texas Legislature. It also holds the governor’s office, the lieutenant governor’s office, and every other statewide office. Indeed, Republicans have majorities sufficient to enact any reform they wish – apart from state constitutional amendments – without securing a single Democrat vote. Texans voted for that result and Texans expect that from their elected officials. To be clear, Texas voters did not vote for bipartisan capitulation or compromise with Democrats, they voted for conservative Republican policies to be enacted. Texas has not elected a Democrat statewide since 1994. Texas voters’ decision to again shut Democrats out of statewide office and return Republican majorities to our Legislative and Congressional Delegations signals voters want the Republican Party of Texas Platform rigorously pursued and they expect results – not excuses. In order to advance the Republican Party of Texas Platform and its 87th Session Legislative Priorities, any Republican campaigning for Speaker of the Texas House should and must commit the following to Republican voters: ● Each Republican Party of Texas legislative priority will receive a vote on the floor of the Texas House. ● All House committees shall be chaired by Republicans and shall be composed of a majority of Republicans. -

The Misrepresented Road to Madame President: Media Coverage of Female Candidates for National Office

THE MISREPRESENTED ROAD TO MADAME PRESIDENT: MEDIA COVERAGE OF FEMALE CANDIDATES FOR NATIONAL OFFICE by Jessica Pinckney A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Government Baltimore, Maryland May, 2015 © 2015 Jessica Pinckney All Rights Reserved Abstract While women represent over fifty percent of the U.S. population, it is blatantly clear that they are not as equally represented in leadership positions in the government and in private institutions. Despite their representation throughout the nation, women only make up twenty percent of the House and Senate. That is far from a representative number and something that really hurts our society as a whole. While these inequalities exist, they are perpetuated by the world in which we live, where the media plays a heavy role in molding peoples’ opinions, both consciously and subconsciously. The way in which the media presents news about women is not always representative of the women themselves and influences public opinion a great deal, which can also affect women’s ability to rise to the top, thereby breaking the ultimate glass ceilings. This research looks at a number of cases in which female politicians ran for and/or were elected to political positions at the national level (President, Vice President, and Congress) and seeks to look at the progress, or lack thereof, in media’s portrayal of female candidates running for office. The overarching goal of the research is to simply show examples of biased and unbiased coverage and address the negative or positive ways in which that coverage influences the candidate. -

The Impact of the New Right on the Reagan Administration

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THE IMPACT OF THE NEW RIGHT ON THE REAGAN ADMINISTRATION: KIRKPATRICK & UNESCO AS. A TEST CASE BY Isaac Izy Kfir LONDON 1998 UMI Number: U148638 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U148638 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this research is to investigate whether the Reagan administration was influenced by ‘New Right’ ideas. Foreign policy issues were chosen as test cases because the presidency has more power in this area which is why it could promote an aggressive stance toward the United Nations and encourage withdrawal from UNESCO with little impunity. Chapter 1 deals with American society after 1945. It shows how the ground was set for the rise of Reagan and the New Right as America moved from a strong affinity with New Deal liberalism to a new form of conservatism, which the New Right and Reagan epitomised. Chapter 2 analyses the New Right as a coalition of three distinctive groups: anti-liberals, New Christian Right, and neoconservatives. -

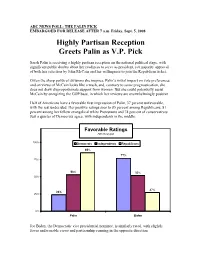

Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin As V.P. Pick

ABC NEWS POLL: THE PALIN PICK EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 7 a.m. Friday, Sept. 5, 2008 Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin as V.P. Pick Sarah Palin is receiving a highly partisan reception on the national political stage, with significant public doubts about her readiness to serve as president, yet majority approval of both her selection by John McCain and her willingness to join the Republican ticket. Given the sharp political divisions she inspires, Palin’s initial impact on vote preferences and on views of McCain looks like a wash, and, contrary to some prognostication, she does not draw disproportionate support from women. But she could potentially assist McCain by energizing the GOP base, in which her reviews are overwhelmingly positive. Half of Americans have a favorable first impression of Palin, 37 percent unfavorable, with the rest undecided. Her positive ratings soar to 85 percent among Republicans, 81 percent among her fellow evangelical white Protestants and 74 percent of conservatives. Just a quarter of Democrats agree, with independents in the middle. Favorable Ratings ABC News poll 100% Democrats Independents Republicans 85% 77% 75% 53% 52% 50% 27% 24% 25% 0% Palin Biden Joe Biden, the Democratic vice presidential nominee, is similarly rated, with slightly fewer unfavorable views and partisanship running in the opposite direction. Palin: Biden: Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable All 50% 37 54% 30 Democrats 24 63 77 9 Independents 53 34 52 31 Republicans 85 7 27 60 Men 54 37 55 35 Women 47 36 54 27 IMPACT – The public by a narrow 6-point margin, 25 percent to 19 percent, says Palin’s selection makes them more likely to support McCain, less than the 12-point positive impact of Biden on the Democratic ticket (22 percent more likely to support Barack Obama, 10 percent less so). -

Reflections on Russell Kirk Lee Trepanier Saginaw Valley State University

Russell Kirk: A Centennial Symposium Reflections on Russell Kirk Lee Trepanier Saginaw Valley State University A century has passed since the birth of Russell Kirk (1918-94), one of the principal founders of the post-World War II conservative revival in the United States.1 This symposium examines Kirk’s legacy with a view to his understanding of constitutional law and the American Founding. But before we examine these essays, it is worth a moment to review Kirk’s life, thought, and place in American conservatism. Russell Kirk was born and raised in Michigan and obtained his B.A. in history at Michigan State University and his M.A. at Duke Univer- sity, where he studied John Randolph of Roanoke and discovered the writings of Edmund Burke.2 His book Randolph of Roanoke: A Study in Conservative Thought (1951) would endure as one of his most important LEE TREPANIER is Professor of Political Science at Saginaw Valley State University. He is also the editor of Lexington Books’ series “Politics, Literature, and Film” and of the aca- demic website VoegelinView. 1 I would like to thank the McConnell Center at the University of Louisville for sponsoring a panel related to this symposium at the 2018 American Political Science Conference and Zachary German for his constructive comments on these papers. I also would like to thank Richard Avramenko of the Center for the Study of Liberal Democracy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Saginaw Valley State University for supporting my sabbatical, which enabled me to write this article and organize this symposium for Humanitas. -

The Educational Ideas of Irving Babbitt

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1974 The ducE ational Ideas of Irving Babbitt: Critical Humanism and American Higher Education Joseph Aldo Barney Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Barney, Joseph Aldo, "The ducaE tional Ideas of Irving Babbitt: Critical Humanism and American Higher Education" (1974). Dissertations. Paper 1363. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1363 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1974 Joseph Aldo Barney The Educational Ideas of Irving Babbitt: Critical Humanism and .American Higher Education by Joseph Aldo Barney A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 1974 VITA Joseph Aldo Barney was born January 11, 1940 in the city of Chicago. He attended Our Lady Help of Christians Grammar School, Sto Mel High School and, in 1967, received the degree of Bachelor of Science from Loyola University of Chicago. During the period 1967 to present, Mr. Barney continued his studies at Loyola University, earning the degree of Master of Education in 1970 and the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in 1974. Mr. Barney's occupational pursuits have centered about university administration and teachingo He was employed by Loyola University of Chicago from 1961 to 1973 in various administrative capacities. -

Giuseppe Prezzolini

Giuseppe Prezzolini MANIFESTO DEI CONSERVATORI 1972 Giuseppe Prezzolini MANIFESTO DEI CONSERVATORI 1972 Opera disponibile su www.archive.org con licenza Attribuzione - Non opere derivate 4.0 lnternazionale (CC BY-ND 4.0) PREFAZIONE Nel settembre del 1971 Veditore Rusconi mi chiese di radunare in un libretto quello che avevo va- rie volte scritto per difendere la malfamata parola di «conservatore». Essendo sempre stato fin da giovanissimo d’ac- cordo con le minoranze e spesse volte quindi diven- tato critico della democrazia, accettai subito e mi provai a stabilire su quali basi si poteva seriamente fondare l’ideale di un conservatore al tempo nostro. Ma quando ebbi esaminato il problema dal punto di vista semantico, filosofico, biologico, sociologico, storico, politico, e trovato fra tutti una certa concor- danza, pensai che forse al pubblico sarebbe stata più interessante una storia personale del mio, per dire così, pensiero politico. Andai a rovistare in giornali, in riviste e in libri ed accumulai molti appunti e ritagli e vidi che met- tendoli in fila uno dopo l’altro mi annoiavo. Pensai, allora, di divertirmi commentando quei tentativi miei di comprendere e di agire sul mondo politico nel quale mi sono trovato, e li intramezzai di ricordi, di aneddoti, di panorami, tutti schizzati alla svelta. Lo mandai e piacque all'Editore, che era stato soddisfatto di un mio libro che tocca il problema della politica (Cristo e/o Machiavelli), lo lesse in ab- bozzo e m'invitò a pubblicarlo in volume. Eccolo qui. 3 4 Parte prima 1. SEMANTICA DELLA PAROLA «CONSERVAZIONE» Userò il termine di «conservatori» invece di quello di «destra», perché il nome di «destra» ha soltanto un significato di luogo, ed è accidentale. -

CONSTITUTING CONSERVATISM: the GOLDWATER/PAUL ANALOG by Eric Edward English B. A. in Communication, Philosophy, and Political Sc

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt CONSTITUTING CONSERVATISM: THE GOLDWATER/PAUL ANALOG by Eric Edward English B. A. in Communication, Philosophy, and Political Science, University of Pittsburgh, 2001 M. A. in Communication, University of Pittsburgh, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eric Edward English It was defended on November 13, 2013 and approved by Don Bialostosky, PhD, Professor, English Gordon Mitchell, PhD, Associate Professor, Communication John Poulakos, PhD, Associate Professor, Communication Dissertation Director: John Lyne, PhD, Professor, Communication ii Copyright © by Eric Edward English 2013 iii CONSTITUTING CONSERVATISM: THE GOLDWATER/PAUL ANALOG Eric Edward English, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 Barry Goldwater’s 1960 campaign text The Conscience of a Conservative delivered a message of individual freedom and strictly limited government power in order to unite the fractured American conservative movement around a set of core principles. The coalition Goldwater helped constitute among libertarians, traditionalists, and anticommunists would dominate American politics for several decades. By 2008, however, the cracks in this edifice had become apparent, and the future of the movement was in clear jeopardy. That year, Ron Paul’s campaign text The Revolution: A Manifesto appeared, offering a broad vision of “freedom” strikingly similar to that of Goldwater, but differing in certain key ways. This book was an effort to reconstitute the conservative movement by expelling the hawkish descendants of the anticommunists and depicting the noninterventionist views of pre-Cold War conservatives like Robert Taft as the “true” conservative position. -

Izembek Comment Analysis Report 2010

JULY 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF APPENDICES ............................................................................................................................ ii ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................. iii 1.0 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 THE ROLE OF PUBLIC COMMENT ............................................................................... 1 1.3 ANALYSIS OF PUBLIC COMMENT .............................................................................. 2 2.0 STATEMENTS OF CONCERN .................................................................................................. 8 Biological Resources - General (BIO) ............................................................................................. 9 Biological Resources - Fish (BIO FISH) ...................................................................................... 10 Biological Resources - Threatened & Endangered Species (BIO T&E) -

John S. Mccain III • Born in Panama on August 29, 1936 • Nicknamed

John S. McCain III • Born in Panama on August 29, 1936 • Nicknamed ”The Maverick” for not being afraid to disagree with his political party (Republican) • Naval aviator during the Vietnam War • Prisoner of war in Vietnam from 1967-1973 • Arizona senator since 1986 • Republican nominee for president of the United States in 2008 McCain in the Navy McCain’s father and grandfather were both admirals in the Navy. He followed in their footsteps and graduated from the Naval Academy in 1958. He is pictured here with his parents and his younger brother, Joe. His son, Jimmy, also became an officer in the Navy McCain in training (1965) As the U.S. began to increase the number of troops in Vietnam in 1965, McCain was training to become a fighter pilot. On October 26, 1967, his A-4 Skyhawk was shot down by a missile as he was flying over Hanoi. He was badly injured when he was pulled from Truc Bach Lake by North Vietnamese. Shot Down McCain’s bomber was hit by a surface-to-air missile on Oct. 26, 1967, destroying the aircraft’s right wing. According to McCain, the plane entered an “inverted, almost straight-down spin,” and he ejected. But the sheer force of the ejection broke his right leg and both arms, knocking him unconscious, the report said. McCain came to as he landed in a lake, but burdened by heavy equipment, he sank straight to the bottom. Able to kick to the surface momentarily for air, he somehow managed to activate his life preserver with his teeth. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-06921-3 - The United States in a Warming World: The Political Economy of Government, Business, and Public Responses to Climate Change Thomas L. Brewer Index More information Index acid rain, California 3 opposition to cap-and-trade 7 ACORE (The American Council for Renewable opposition to mitigation measures 70 Energy) 163 American Power Act (2009) 161–163 adaptation measures 155 alternative bills 162, 184(Appendix) developing countries 226 discussion draft 184 financing 226, 242(Table), 241–243, 292 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) monitoring 243 189, 221 adoption externalities 199 budget 212(Figure), 213(Table), 210–214 aerosols, restrictions on (California) 141 comparison with other countries 213(Table) AFL-CIO 65 funding levels 202 age, and opinion on climate change issues 105 home insulation subsidy 203 agriculture 56 American Wind Energy Association 73 and biofuels subsidies 203 analytic framework 23(Figure), 16–23 dairy industry 32 issue clusters 21, 22(Figure), 22(Table) and drought 35 Arrhenius, Svante August 46 effect of high temperatures on 33 Asia-Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and emissions 27 Climate (APP) 216, 252 methane from 24 asymmetric distribution, of mitigation costs and sequestration 27 benefits 17, 19(Figure), 20, 270 and Waxman–Markey bill 158 auto industry 30(Map) airline industry 246 and Californian restrictions on tailpipe emissions Alaska 136 climate change impacts 33, 155 and electric automobiles 97 per-capita emissions 43 emissions 27 sources and impacts conflict 34 and GCC 70 Alcoa company 56 unions 67 Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers 67 USA lagging behind foreign rivals 58, 76 alternative energy industry 76 and Waxman–Markey bill 158 lobbying by 73 see also motor vehicles see also clean energy; renewable energy Alternative Fuels Act (1988) 220 Bachmann, Michelle, Tea Party Caucus 172 aluminum industry 56 Balanced Energy Coalition, George W. -

Vmagwtr03 P30-59.Final (Page 30

By PAUL KINGSBURY, BA’80 The thorny legacy of Vanderbilt’s Fugitives and Agrarians Pride and Prejudice t’s one of the most famous and cherished photographs in Vanderbilt’s history. Allen Tate, Merrill Moore, Robert Penn Warren, John Crowe Ransom, Donald Davidson. Five balding white men, dressed impeccably in suits and ties, are seated outdoors, Iobviously posed by photographer Joe Rudis to appear as if lost in con- versation. Despite the artifice, the subjects seem relaxed and even playful, what with Moore practically sitting on Tate’s lap, Warren lean- ing in as if to insert a word edgewise, and the entire group looking to Allen Tate as if expecting a clever remark. It was a happy moment for the old friends. It was 1956, and after three decades of being ignored by the University, the Fugitives had returned to campus in glory for a colloquium devoted to their literary work. V anderbilt Magazine 31 Heroes Fugitives and Agrarians he five writers photographed in 1956 “Nothing in Vanderbilt’s history has come devoted to the Fugitives and Agrarians. The undergraduate courses on southern litera- were Vanderbilt graduates. They were anywhere close to the Fugitives and Agrari- 1956 reunion was followed by an Agrarian ture to these writers. On the graduate level, Donald Davidson (1893–1968) known as “Fugitives” after The Fugi- ans in giving it a national reputation,”con- reunion and symposium in 1980. That event, Kreyling says master’s and doctoral students BA’17, MA’22; Vanderbilt Ttive, the widely praised but little purchased firms Paul Conkin, distinguished professor though, seemed to mark a high tide for the in his department read them only occasion- English department, poetry magazine they self-published, along of history, emeritus, and the author of defin- Agrarians and Fugitives on campus.