An Early History of the 'By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Four Courts of Sir Lyman Duff

THE FOUR COURTS OF SIR LYMAN DUFF RICHARD GOSSE* Vancouver I. Introduction. Sir Lyman Poore Duff is the dominating figure in the Supreme Court of Canada's first hundred years. He sat on the court for more than one-third of those years, in the middle period, from 1906 to 1944, participating in nearly 2,000 judgments-and throughout that tenure he was commonly regarded as the court's most able judge. Appointed at forty-one, Duff has been the youngest person ever to have been elevated to the court. Twice his appointment was extended by special Acts of Parliament beyond the mandatory retirement age of seventy-five, a recogni- tion never accorded to any other Canadian judge. From 1933, he sat as Chief Justice, having twice previously-in 1918 and 1924 - almost succeeded to that post, although on those occasions he was not the senior judge. During World War 1, when Borden considered resigning over the conscription issue and recommending to the Governor General that an impartial national figure be called upon to form a government, the person foremost in his mind was Duff, although Sir Lyman had never been elected to public office. After Borden had found that he had the support to continue himself, Duff was invited to join the Cabinet but declined. Mackenzie King con- sidered recommending Duff for appointment as the first Canadian Governor General. Duff undertook several inquiries of national interest for the federal government, of particular significance being the 1931-32 Royal Commission on Transportation, of which he was chairman, and the 1942 investigation into the sending of Canadian troops to Hong Kong, in which he was the sole commissioner . -

Compensation for Wrongful Convictions: a Study Towards an Effective Regime of Tort Liability

Compensation for Wrongful Convictions: A study towards an effective regime of tort liability by Laura Patricia Mijares A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Graduate Department of Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Laura Patricia Mijares 2012 Compensation for Wrongful Convictions: A study towards an effective regime of tort liability Laura Patricia Mijares Master of Laws Graduate Department of Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2012 Abstract How would you feel if after having spent many years incarcerated for a crime that you did not commit and when finally you are released to a broken life where there is nobody to respond effectively to all the damages that you have and that you will continue to endure due to an unfortunate miscarriage of justice? In Canada, compensation for wrongful convictions is a legal issue which has yet to find a solution for those who the government has denied to pay compensation for and the damages such wrongful conviction brought to their lives. This thesis will analyze the legal problem of compensation for wrongful convictions in Canada from a tort law perspective and will present an alternative to the existing regime to serve justice to those who have been victims of miscarriages of justice. ii Acknowledgments A new start is never easy. Actually, I believe that starting a new life in this country represents a challenge from which one expects to learn, but overall, to succeed. In my journey of challenges, and especially in this one, I would like to thank the persons whose effort made this challenge a successful one. -

1050 the ANNUAL REGISTER Or the Immediate Vicinity. Hon. E. M. W

1050 THE ANNUAL REGISTER or the immediate vicinity. Hon. E. M. W. McDougall, a Puisne Judge of the Superior Court for the Province of Quebec: to be Puisne Judge of the Court of King's Bench in and for the Province of Quebec, with residence at Montreal or the immediate vicinity. Pierre Emdle Cote, K.C., New Carlisle, Que.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Superior Court in and for the Province of Quebec, effective Oct. 1942, with residence at Quebec or the immediate vicinity. Dec. 15, Henry Irving Bird, Vancouver, B.C.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of British Columbia, with residence at Vancouver, or the immediate vicinity. Frederick H. Barlow, Toronto, Ont., Master of the Supreme Court of Ontario: to be a Judge of the High Court of Justice for Ontario. Roy L. Kellock, K.C., Toronto, Ont.: to be a Justice of the Court of Appeal for Ontario and ex officio a Judge of the High Court of Juscico for Ontario. 1943. Feb. 4, Robert E. Laidlaw, K.C., Toronto, Ont.: to be a Justice of the Court of Appeal for Ontario and ex officio a Judge of the High Court of Justice for Ontario. Apr. 22, Hon. Thane Alexander Campbell, K.C., Summer- side, P.E.I.: to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature of P.E.I. Ivan Cleveland Rand, K.C., Moncton, N.B.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Canada. July 5, Hon. Justice Harold Bruce Robertson, a Judge of the Supreme Court of British Columbia: to be a Justice of Appeal of the Court of Appeal for British Columbia. -

Truscott (Re) (August 28, 2007)

CITATION: Truscott (Re), 2007 ONCA 575 DATE: 20070828 DOCKET: C42726 COURT OF APPEAL FOR ONTARIO MCMURTRY C.J.O., DOHERTY, WEILER, ROSENBERG and MOLDAVER JJ.A. IN THE MATTER OF SECTION 696.3 OF THE CRIMINAL CODE, S.C. 2002, C. 13; AND IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION FOR MINISTERIAL REVIEW (MISCARRIAGES OF JUSTICE) SUBMITTED BY STEVEN MURRAY TRUSCOTT IN RESPECT OF HIS CONVICTION AT GODERICH, ONTARIO, ON SEPTEMBER 30, 1959, FOR THE MURDER OF LYNNE HARPER; AND IN THE MATTER OF THE DECISION OF THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE TO REFER THE SAID CONVICTION TO THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR ONTARIO FOR HEARING AND DETERMINATION AS IF IT WERE AN APPEAL BY STEVEN MURRAY TRUSCOTT ON THE ISSUE OF FRESH EVIDENCE, PURSUANT TO SUBSECTION 696.3(3)(a)(ii) OF THE CRIMINAL CODE. B E T W E E N: HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN ) James Lockyer, Philip Campbell, ) Marlys Edwardh, Hersh E. Wolch, ) Q.C. and Jenny Friedland, for the ) appellant ) (Respondent) ) ) - and - ) ) STEVEN MURRAY TRUSCOTT ) Rosella Cornaviera, Gregory J. ) Tweney, Alexander Alvaro and ) Leanne Salel, for the respondent ) (Appellant) ) HEARD: January 31, February 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13 and 14, 2007 Page: 2 PART I – INTRODUCTION............................................................................................7 Overview of the Case.....................................................................................................7 History of the Proceedings Involving the Appellant ..................................................9 Overview of the Case for the Crown and the Defence in the Prior Proceedings...15 -

A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962

8 A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962 When the newly paramount Supreme Court of Canada met for the first timeearlyin 1950,nothing marked theoccasionasspecial. ltwastypicalof much of the institution's history and reflective of its continuing subsidiary status that the event would be allowed to pass without formal recogni- tion. Chief Justice Rinfret had hoped to draw public attention to the Court'snew position throughanotherformalopeningofthebuilding, ora reception, or a dinner. But the government claimed that it could find no funds to cover the expenses; after discussing the matter, the cabinet decided not to ask Parliament for the money because it might give rise to a controversial debate over the Court. Justice Kerwin reported, 'They [the cabinet ministers] decided that they could not ask fora vote in Parliament in theestimates tocoversuchexpensesas they wereafraid that that would give rise to many difficulties, and possibly some unpleasantness." The considerable attention paid to the Supreme Court over the previous few years and the changes in its structure had opened broader debate on aspects of the Court than the federal government was willing to tolerate. The government accordingly avoided making the Court a subject of special attention, even on theimportant occasion of itsindependence. As a result, the Court reverted to a less prominent position in Ottawa, and the status quo ante was confirmed. But the desire to avoid debate about the Court discouraged the possibility of change (and potentially of improvement). The St Laurent and Diefenbaker appointments during the first decade A Decade of Adjustment 197 following termination of appeals showed no apparent recognition of the Court’s new status. -

Review of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical

A JUDICIAL LOUDMOUTH WITH A QUIET LEGACY: A REVIEW OF EMMETT HALL: ESTABLISHMENT RADICAL DARCY L. MACPHERSON* n the revised and updated version of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical, 1 journalist Dennis Gruending paints a compelling portrait of a man whose life’s work may not be directly known by today’s younger generation. But I Gruending makes the point quite convincingly that, without Emmett Hall, some of the most basic rights many of us cherish might very well not exist, or would exist in a form quite different from that on which Canadians have come to rely. The original version of the book was published in 1985, that is, just after the patriation of the Canadian Constitution, and the entrenchment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,2 only three years earlier. By 1985, cases under the Charter had just begun to percolate up to the Supreme Court of Canada, a court on which Justice Hall served for over a decade, beginning with his appointment in late 1962. The later edition was published two decades later (and ten years after the death of its subject), ostensibly because events in which Justice Hall had a significant role (including the Canadian medicare system, the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Stephen Truscott, and claims of Aboriginal title to land in British Columbia) still had currency and relevance in contemporary Canadian society. Despite some areas where the new edition may be considered to fall short which I will mention in due course, this book was a tremendous read, both for those with legal training, and, I suspect, for those without such training as well. -

REGISTER of OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS 1165 Hon. J

REGISTER OF OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS 1165 Hon. J. Watson MacNaught: to be a member of the Administration. Hon. Roger Teillet: to be Minister of Veterans Affairs. Hon. Judy LaMarsh: to be Minister of National Health and Welfare. Hon. Charles Mills Drury: to be Minister of Defence Production. Hon. Guy Favreau: to be Minister of Citizenship and Immigration. Hon. John Robert Nichol son: to be Minister of Forestry. Hon. Harry Hays: to be Minister of Agriculture. Hon. Rene" Tremblay: to be a member of the Administration. May 23, Hon. Robert Gordon Robertson: to be Secretary to the Cabinet, from July 1, 1963. July 25, Hon. Charles Mills Drury: to be Minister of Industry. Aug. 14, Hon. Maurice Lamontagne: to act as the Minister for the purposes of the Economic Council of Canada Act. Senate Appointments.—1962. Sept. 24, Hon. George Stanley White, a member of the Senate: to be Speaker of the Senate. M. Grattan O'Leary, Ottawa, Ont.: to be a Senator for the Province of Ontario. Edgar Fournier, Iroquois, N.B.: to be a Senator for the Province of New Brunswick. Allister Grosart, Ottawa, Ont.: to be a Senator for the Province of Ontario. Sept. 25, Frank Welch, Wolfville, N.S.: to be a Senator for the Province of Nova Scotia. Clement O'Leary, Antigonish, N.S.: to be a Senator for the Province of Nova Scotia. Nov. 13, Jacques Flynn, Quebec, Que.: to be a Senator for the Province of Quebec. Nov. 29, John Alexander Robertson, Kenora, Ont.: to be a Senator for the Province of Ontario. 1963. Feb. -

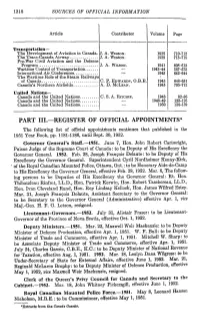

PART III.—REGISTER of OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS* the Following List of Official Appointments Continues That Published in the 1951 Year Book, Pp

1218 SOURCES OF OFFICIAL INFORMATION Article Contributor Volume Page Transportation— The Development of Aviation in Canada. J. A. WILSON. 1938 710-712 The Trans-Canada Airway J. A. WILSON. 1938 713-715 Pre-War Civil Aviation and the Defence Program J. A. WILSON. 1941 608-612 Wartime Control of Transportation 1943-14 567-575 International Air Conferences 1945 642-644 The Wartime Role of the Steam Railways of Canada C. P. EDWARDS, O.B.E. 1945 648-651 Canada's Northern Airfields A. D. MCLEAN. 1945 705-712 United Nations- Canada and the United Nations C. S. A. RITCHIE. 1946 82-86 Canada and the United Nations 1948-49 122-125 Canada and the United Nations 1950 134-139 PART III.—REGISTER OF OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS* The following list of official appointments continues that published in the 1951 Year Book, pp. 1181-1186, until Sept. 30, 1952. Governor General's Staff.—1951. June 7, Hon. John Robert Cartwright, Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Canada: to be Deputy of His Excellency the Governor General. 1952. Feb. 28, Joseph Francois Delaute: to be Deputy of His Excellency the Governor General. Superintendent Cyril Nordheimer Kenny-Kirk, of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Ottawa, Ont.: to be Honorary Aide-de-Camp to His Excellency the Governor General, effective Feb. 28, 1952. Mar. 6, The follow ing persons to be Deputies of His Excellency the Governor General: Rt. Hon. Thibaudeau Rinfret, LL.D., Hon. Patrick Kerwin, Hon. Robert Taschereau, LL.D., Hon. Ivan Cleveland Rand, Hon. Roy Lindsay Kellock, Hon. James Wilfred Estey. Mar. -

Rule of Law Report

RULE OF LAW REPORT ISSUE 2 JUNE 2018 EDITOR’S NOTE Heather MacIvor 2 TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF ADVOCACY FOR THE WRONGLY CONVICTED Win Wahrer 3 LEVEL – CHANGING LIVES THROUGH LAW Heather MacIvor 6 EDITOR’S NOTE This issue features two leading Canadian organizations dedicated to justice and the rule of law. Innocence Canada, formerly called AIDWYC (Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted), is dedicated to preventing and correcting miscarriages of justice. Win Wahrer Heather MacIvor has been with Innocence Canada since LexisNexis Canada the beginning. As the organization celebrates its 25th anniversary, Win tells its story. She also spotlights some of the remarkable individuals who support Innocence Canada, and those Photo by Fardeen Firoze whom it has supported in their struggles. Level, formerly Canadian Lawyers Abroad, targets barriers to justice. It aims to educate and empower Indigenous youth, enhance cultural competency in the bench and Bar, and mentor future leaders in the legal profession. This issue spotlights Level’s current programming and its new five-year strategic plan. By drawing attention to flaws in the legal system, and tackling the root causes of injustice, Innocence Canada and Level strengthen the rule of law. LexisNexis Canada and its employees are proud to support the work of both organizations. We also raise money for other worthy causes, including the #TorontoStrongFund, established in response to the April 2018 Toronto van attack. 2 TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF ADVOCACY FOR THE WRONGLY CONVICTED Innocence Canada, formerly the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted (AIDWYC), is a national, non-profit organization that advocates for the wrongly convicted across Canada. -

Ian Bushnell*

JUstice ivan rand and the roLe of a JUdge in the nation’s highest coUrt Ian Bushnell* INTRODUCTION What is the proper role for the judiciary in the governance of a country? This must be the most fundamental question when the work of judges is examined. It is a constitutional question. Naturally, the judicial role or, more specifically, the method of judicial decision-making, critically affects how lawyers function before the courts, i.e., what should be the content of the legal argument? What facts are needed? At an even more basic level, it affects the education that lawyers should experience. The present focus of attention is Ivan Cleveland Rand, a justice of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1943 until 1959 and widely reputed to be one of the greatest judges on that Court. His reputation is generally based on his method of decision-making, a method said to have been missing in the work of other judges of his time. The Rand legal method, based on his view of the judicial function, placed him in illustrious company. His work exemplified the traditional common law approach as seen in the works of classic writers and judges such as Sir Edward Coke, Sir Matthew Hale, Sir William Blackstone, and Lord Mansfield. And he was in company with modern jurists whose names command respect, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and Benjamin Cardozo, as well as a law professor of Rand at Harvard, Roscoe Pound. In his judicial decisions, addresses and other writings, he kept no secrets about his approach and his view of the judicial role. -

Review of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical

A JUDICIAL LOUDMOUTH WITH A QUIET LEGACY: A REVIEW OF EMMETT HALL: ESTABLISHMENT RADICAL DARCY L. MACPHERSON* n the revised and updated version of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical, 1 journalist Dennis Gruending paints a compelling portrait of a man whose life’s work may not be directly known by today’s younger generation. But I Gruending makes the point quite convincingly that, without Emmett Hall, some of the most basic rights many of us cherish might very well not exist, or would exist in a form quite different from that on which Canadians have come to rely. The original version of the book was published in 1985, that is, just after the patriation of the Canadian 2008 CanLIIDocs 196 Constitution, and the entrenchment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,2 only three years earlier. By 1985, cases under the Charter had just begun to percolate up to the Supreme Court of Canada, a court on which Justice Hall served for over a decade, beginning with his appointment in late 1962. The later edition was published two decades later (and ten years after the death of its subject), ostensibly because events in which Justice Hall had a significant role (including the Canadian medicare system, the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Stephen Truscott, and claims of Aboriginal title to land in British Columbia) still had currency and relevance in contemporary Canadian society. Despite some areas where the new edition may be considered to fall short which I will mention in due course, this book was a tremendous read, both for those with legal training, and, I suspect, for those without such training as well. -

The Supremecourt History Of

The SupremeCourt of Canada History of the Institution JAMES G. SNELL and FREDERICK VAUGHAN The Osgoode Society 0 The Osgoode Society 1985 Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-34179 (cloth) Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Snell, James G. The Supreme Court of Canada lncludes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-802@34179 (bound). - ISBN 08020-3418-7 (pbk.) 1. Canada. Supreme Court - History. I. Vaughan, Frederick. 11. Osgoode Society. 111. Title. ~~8244.5661985 347.71'035 C85-398533-1 Picture credits: all pictures are from the Supreme Court photographic collection except the following: Duff - private collection of David R. Williams, Q.c.;Rand - Public Archives of Canada PA@~I; Laskin - Gilbert Studios, Toronto; Dickson - Michael Bedford, Ottawa. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Social Science Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA History of the Institution Unknown and uncelebrated by the public, overshadowed and frequently overruled by the Privy Council, the Supreme Court of Canada before 1949 occupied a rather humble place in Canadian jurisprudence as an intermediate court of appeal. Today its name more accurately reflects its function: it is the court of ultimate appeal and the arbiter of Canada's constitutionalquestions. Appointment to its bench is the highest achieve- ment to which a member of the legal profession can aspire. This history traces the development of the Supreme Court of Canada from its establishment in the earliest days following Confederation, through itsattainment of independence from the Judicial Committeeof the Privy Council in 1949, to the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982.