Black Theatre Survey 2016-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brian Stokes Mitchell Outside at the Colonial

Press Contacts: Katie B. Watts Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For immediate release, please: Monday, July 20 at 10am Berkshire Theatre Group Announces An Intimate Performance with Two-time Tony Award-winner Brian Stokes Mitchell to Benefit Berkshire Theatre Group and a Portion of Sales to go to The Actors Fund and Black Theatre United Pittsfield, MA – Berkshire Theatre Group (BTG) and Kate Maguire (Artistic Director, CEO) are excited to announce two-time Tony Award-winner Brian Stokes Mitchell in an intimate performance and fundraiser to benefit Berkshire Theatre Group. In this very special one-night-only concert, Brian Stokes Mitchell will deliver an unforgettable performance to an audience of less than 100 people, outside under a tent at The Colonial Theatre on Labor Day Weekend, September 5 at 8pm. Dubbed “the last leading man” by The New York Times, Tony Award-winner Brian Stokes Mitchell has enjoyed a career that spans Broadway, television, film, and concert appearances with the country’s finest conductors and orchestras. He received Tony, Drama Desk, and Outer Critics Circle awards for his star turn in Kiss Me, Kate. He also gave Tony-nominated performances in Man of La Mancha, August Wilson’s King Hedley II, and Ragtime. Other notable Broadway shows include: Kiss of the Spider Woman, Jelly’s Last Jam, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and Shuffle Along. In 2016 he was awarded his second Tony Award, the prestigious Isabelle Stevenson Tony for his Charitable work with The Actors Fund. -

2021 Hcn Media

HARLEM COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERS, INC. We deliver the “good news” to improve the quality of life for our readers, their families, and our communities The Harlem Community Newspapers, Inc. Connecting Harlem, Queens, Brooklyn and The Bronx The Harlem Community Newspapers, Inc. Connecting Harlem, Queens, Brooklyn and The Bronx The Harlem Community Newspapers, Inc. Connecting Harlem, Queens, Brooklyn and The Bronx COMMUNITY The Harlem Community Newspapers, Inc. Connecting Harlem, Queens, Brooklyn and The Bronx COMMUNITY COMMUNITY HARLEM NEWS COMMUNITY BROOKLYN NEWS QUEENS NEWS “Good News You Can Use” BRONX NEWS “Good News You Can Use” “Good News You Can Use” Vol. 23 No. 12 March 22 - March 28, 2018 FREE “Good News You Can Use” Vol. 23 No. 24 June 14 - June 20, 2018 FREE Vol. 23 No. 25 June 21 - June 27, 2018 FREE Vol. 23 No. 22 May 31 - June 6, 2018 FREE New York Urban League rd Celebrates 53 Annual Women in the Fidelis Care Black’s 20th Annual Sponsors Senior Harlem’s Heaven Who’s The Boss Unity Day in Hats at Fashion Conference 2018 see page 11 Riverbank State Week Frederick Douglass Awards see pages 12-13 CACCI Celebrate Caribbean Park see page 4 Uptown’s Business Women Come Will and Jada Smith see pages 14-15 Family Foundation in Harlem see page 10 American Heritage Month Together for Day of Empowerment see page 11 at Borough Hall see page 10 Innovative Disney Summertime Fun @ Dreamers Academy Sugar Hill Children’s impacts lives Museum forever The NCNW’s 31st see page 13 see page 25 Annual Black and Golden Life Ministry White Awards Keeping It Real! see page 11 see page 14 National Black Theatre th Ruben Santiago- Celebrates at 10 Annual TEER Hudson directs a magic cast Whitney Moore in Dominique Young, Jr. -

A History of African American Theatre Errol G

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-62472-5 - A History of African American Theatre Errol G. Hill and James V. Hatch Frontmatter More information AHistory of African American Theatre This is the first definitive history of African American theatre. The text embraces awidegeographyinvestigating companies from coast to coast as well as the anglo- phoneCaribbean and African American companies touring Europe, Australia, and Africa. This history represents a catholicity of styles – from African ritual born out of slavery to European forms, from amateur to professional. It covers nearly two and ahalf centuries of black performance and production with issues of gender, class, and race ever in attendance. The volume encompasses aspects of performance such as minstrel, vaudeville, cabaret acts, musicals, and opera. Shows by white playwrights that used black casts, particularly in music and dance, are included, as are produc- tions of western classics and a host of Shakespeare plays. The breadth and vitality of black theatre history, from the individual performance to large-scale company productions, from political nationalism to integration, are conveyed in this volume. errol g. hill was Professor Emeritus at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire before his death in September 2003.Hetaughtat the University of the West Indies and Ibadan University, Nigeria, before taking up a post at Dartmouth in 1968.His publications include The Trinidad Carnival (1972), The Theatre of Black Americans (1980), Shakespeare in Sable (1984), The Jamaican Stage, 1655–1900 (1992), and The Cambridge Guide to African and Caribbean Theatre (with Martin Banham and George Woodyard, 1994); and he was contributing editor of several collections of Caribbean plays. -

Lady Day at Emerson's Bar & Grill

PRESS RELEASE – FRIDAY 3 FEBRUARY 2017 RECORD SIX-TIME TONY AWARD-WINNER AUDRA McDONALD MAKES HER WEST END DEBUT IN LADY DAY AT EMERSON'S BAR & GRILL WYNDHAM’S THEATRE, LONDON From 17 June to 9 September 2017 PRODUCTION PHOTOGRAPHY AVAILABLE HERE Username: Lady Day | Password: Holiday TICKETS ON SALE HERE FROM MIDDAY ON FRIDAY 3 FEBRUARY After the joyous news of Audra McDonald’s unexpected pregnancy last year, producers of the postponed London run of Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill are delighted to announce that this summer, McDonald, the Tony, Grammy, and Emmy Award-winning singer and actress, will be making her long awaited West End debut portraying jazz legend Billie Holiday in a performance that won her a record-setting sixth Tony Award. This critically acclaimed production, which broke box office records at the Circle in the Square in New York, will run for a limited engagement at Wyndham’s Theatre from Saturday 17 June to Saturday 9 September, with opening night for press on Tuesday 27 June 2017. “Audra McDonald is a vocal genius! One of the greatest performances I ever hope to see.” New York Magazine Written by Lanie Robertson and directed by Lonny Price, Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill recounts Holiday's life story through the songs that made her famous, including “God Bless the Child,” “What a Little Moonlight Can Do,” “Strange Fruit” and “Taint Nobody’s Biz- ness.” “Mesmerizing! Pouring her heart into her voice, Audra McDonald breathes life into Billie Holiday’s greatest songs.” The New York Times Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill won two Tony Awards in 2014 including ‘Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Play’ for Audra McDonald, making her Broadway’s most decorated performer, winner of six Tony Awards and the first and only person to receive awards in all four acting categories. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1982

Nat]onal Endowment for the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1982. Respectfully, F. S. M. Hodsoll Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. March 1983 Contents Chairman’s Statement 3 The Agency and Its Functions 6 The National Council on the Arts 7 Programs 8 Dance 10 Design Arts 30 Expansion Arts 46 Folk Arts 70 Inter-Arts 82 International 96 Literature 98 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television 114 Museum 132 Music 160 Opera-Musical Theater 200 Theater 210 Visual Arts 230 Policy, Planning and Research 252 Challenge Grants 254 Endowment Fellows 259 Research 261 Special Constituencies 262 Office for Partnership 264 Artists in Education 266 State Programs 272 Financial Summary 277 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 278 The descriptions of the 5,090 grants listed in this matching grants, advocacy, and information. In 1982 Annual Report represent a rich variety of terms of public funding, we are complemented at artistic creativity taking place throughout the the state and local levels by state and local arts country. These grants testify to the central impor agencies. tance of the arts in American life and to the TheEndowment’s1982budgetwas$143million. fundamental fact that the arts ate alive and, in State appropriations from 50 states and six special many cases, flourishing, jurisdictions aggregated $120 million--an 8.9 per The diversity of artistic activity in America is cent gain over state appropriations for FY 81. -

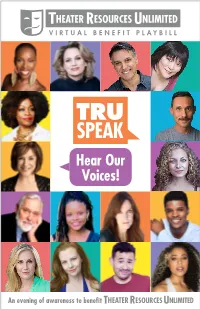

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

November 12, 2017

A Love/Hate Story in Black and White Directed by Lou Bellamy A Penumbra Theatre Company Production October 19 – November 12, 2017 ©2017 Penumbra Theatre Company Wedding Band Penumbra’s 2017-2018 Season: Crossing Lines A Letter from the Artistic Director, Sarah Bellamy Fifty years ago a young couple was thrust into the national spotlight because they fought for their love to be recognized. Richard and Mildred Loving, aptly named, didn’t intend to change history—they just wanted to protect their family. They took their fight to the highest court and with Loving v. The State of Virginia, the Supreme Court declared anti-miscegenation law unconstitutional. The year was 1967. We’re not far from that fight. Even today interracial couples and families are met with curiosity, scrutiny, and in this racially tense time, contempt. They represent an anxiety about a breakdown of racial hierarchy in the U.S. that goes back centuries. In 2017 we find ourselves defending progress we never imagined would be imperiled, but we also find that we are capable of reaching beyond ourselves to imagine our worlds anew. This season we explore what happens when the boundlessness of love meets the boundaries of our identities. Powerful drama and provocative conversations will inspire us to move beyond the barriers of our skin toward the beating of our hearts. Join us to celebrate the courage of those who love outside the lines, who fight to be all of who they are, an in doing so, urge us to manifest a more loving, inclusive America. ©2017 Penumbra Theatre Company 2 Wedding Band Table of Contents Introductory Material ........................................................................................................................ -

(XXXIX:9) Mel Brooks: BLAZING SADDLES (1974, 93M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

October 22, 2019 (XXXIX:9) Mel Brooks: BLAZING SADDLES (1974, 93m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Mel Brooks WRITING Mel Brooks, Norman Steinberg, Richard Pryor, and Alan Uger contributed to writing the screenplay from a story by Andrew Bergman, who also contributed to the screenplay. PRODUCER Michael Hertzberg MUSIC John Morris CINEMATOGRAPHY Joseph F. Biroc EDITING Danford B. Greene and John C. Howard The film was nominated for three Oscars, including Best Actress in a Supporting Role for Madeline Kahn, Best Film Editing for John C. Howard and Danford B. Greene, and for Best Music, Original Song, for John Morris and Mel Brooks, for the song "Blazing Saddles." In 2006, the National Film Preservation Board, USA, selected it for the National Film Registry. CAST Cleavon Little...Bart Gene Wilder...Jim Slim Pickens...Taggart Harvey Korman...Hedley Lamarr Madeline Kahn...Lili Von Shtupp Mel Brooks...Governor Lepetomane / Indian Chief Burton Gilliam...Lyle Alex Karras...Mongo David Huddleston...Olson Johnson Liam Dunn...Rev. Johnson Shows. With Buck Henry, he wrote the hit television comedy John Hillerman...Howard Johnson series Get Smart, which ran from 1965 to 1970. Brooks became George Furth...Van Johnson one of the most successful film directors of the 1970s, with Jack Starrett...Gabby Johnson (as Claude Ennis Starrett Jr.) many of his films being among the top 10 moneymakers of the Carol Arthur...Harriett Johnson year they were released. -

Geffen Lights out Cast FINAL

Media Contact: Zenon Dmytryk Geffen Playhouse [email protected] 310.966.2405 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CAST ANNOUNCED FOR GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE WEST COAST PREMIERE OF LIGHTS OUT: NAT “KING” COLE NOW EXTENDED THROUGH MARCH 17 FEATURING DULÉ HILL AS NAT “KING” COLE ADDITIONAL CAST INCLUDES GISELA ADISA, CONNOR AMACIO MATTHEWS, BRYAN DOBSON, RUBY LEWIS, ZONYA LOVE, MARCIA RODD, BRANDON RUITER AND DANIEL J. WATTS PREVIEWS BEGIN FEBRUARY 5 - OPENING NIGHT IS FEBRUARY 13 LOS ANGELES (December 19, 2018) – Geffen Playhouse today announced the full cast for its production of Lights Out: Nat “King” Cole, written by Tony and Olivier Award nominee Colman Domingo (Summer: The Donna Summer Musical, If Beale Street Could Talk, Fear the Walking Dead) and Patricia McGregor (Place, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Skeleton Crew), directed by Patricia McGregor and featuring Emmy Award nominee Dulé Hill (Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk; The West Wing; Psych) as Nat “King” Cole. This marks the West Coast premiere for the production, which made its world premiere in 2017 at People’s Light, one of Pennsylvania’s largest professional non-profit theaters. Under the auspices of the Geffen Playhouse, the production from People’s Light has been further workshopped, songs have been added and the play has continued to evolve. In addition to Hill, the cast features Gisela Adisa (Beautiful, Sister Act) as Eartha Kitt and others; Connor Amacio Matthews (In the Flow with Connor Amacio) as Billy Preston and others; Bryan Dobson (Jesus Christ Superstar, The Rocky Horror Show) as Producer and others; Ruby Lewis (Marilyn! The New Musical, Jersey Boys) as Betty Hutton, Peggy Lee and others; Zonya Love (Emma and Max, The Color Purple) as Perlina and others; Marcia Rodd (Last of the Red Hot Lovers, Shelter) as Candy and others; Brandon Ruiter (Sex with Strangers, A Picture of Dorian Gray) as Stage Manager and others; and Daniel J. -

Juanita Hall

Debra DeBerry Clerk of Superior Court DeKalb County Juanita Hall November 6, 1901 – February 28, 1968 First African-American Tony Award Winner Juanita (Long) Hall was born on November 6, 1901, in Keyport, New Jersey to an African-American father, Abram Long, a farm laborer and an Irish-American mother, Mary Richardson. Juanita’s mother died when she was an infant and she was raised primarily by her grandmother, who encouraged her interest in music. As a child, Juanita sang in the church choir and became fascinated with the old Negro spirituals she heard at revival meetings. Juanita knew then that she would pursue a career as a singer. At the age of 14, Juanita began teaching Singing at Lincoln House in East Orange, NJ. A few years later, she married actor Clement Hall, however the marriage didn’t last long and they had no children. Clement Hall died in the 1920’s. Juanita went on to attend New York’s Julliard School of Music and studied Orchestra- tion, Harmony, Music Theory and Voice. While teaching music, Juanita had small stage roles and worked with the Hall Johnson Choir, becoming a soloist and serving as assistant director until she formed her own choral group, The Juanita Hall Choir, in 1936. Her choir operated for five years and gave more than 5,000 performances, including radio appearances three times a week. Her choir also performed at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. Juanita performed in several stage productions, but her breakthrough in musical theater came when she appeared in an annual talent show called ”Talent 48.” There, the songwriting team of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, who were in the process of writing the play, South Pacific, heard Juanita sing. -

Diversity in the Arts

Diversity In The Arts: The Past, Present, and Future of African American and Latino Museums, Dance Companies, and Theater Companies A Study by the DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the University of Maryland September 2015 Authors’ Note Introduction The DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the In 1999, Crossroads Theatre Company won the Tony Award University of Maryland has worked since its founding at the for Outstanding Regional Theatre in the United States, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 2001 to first African American organization to earn this distinction. address one aspect of America’s racial divide: the disparity The acclaimed theater, based in New Brunswick, New between arts organizations of color and mainstream arts Jersey, had established a strong national artistic reputation organizations. (Please see Appendix A for a list of African and stood as a central component of the city’s cultural American and Latino organizations with which the Institute revitalization. has collaborated.) Through this work, the DeVos Institute staff has developed a deep and abiding respect for the artistry, That same year, however, financial difficulties forced the passion, and dedication of the artists of color who have theater to cancel several performances because it could not created their own organizations. Our hope is that this project pay for sets, costumes, or actors.1 By the following year, the will initiate action to ensure that the diverse and glorious quilt theater had amassed $2 million in debt, and its major funders that is the American arts ecology will be maintained for future speculated in the press about the organization’s viability.2 generations. -

Broadway Revealed: Behind the Theater Curtain

Broadway Revealed: Behind the Theater Curtain Donald Holder Lighting Designer on the set of Spider‐Man: Turn Off the Dark, Foxwoods Theater, New York, NY, 24” H x 72” W Exhibition Specifications Title: Broadway Revealed: Behind the Theater Curtain Artist: Photographer Stephen Joseph Curator: Carrie Lederer, Curator of Exhibitions and Programs Organizing Institution: Bedford Gallery, Lesher Center for the Arts, 1601 Civic Drive, Walnut Creek, CA 94596 www.bedfordgallery.org Description: The Bedford Gallery is offering an exclusive touring exhibition Broadway Revealed: Behind the Theater Curtain. This extraordinary show brings to life the mystery, glitz and over‐the‐top grandeur of New York’s most impressive Broadway theater shows. For the last three years, Bay Area photographer Stephen Joseph has captured images of the “giants” of New York theater—directors, set designers, costumers, tailors, and milliners that transform Broadway nightly. The exhibition includes many behind‐the‐scenes shots of these production artists at work in their studios, as well as stage imagery from many well‐known Broadway productions such as American Idiot, Hair, Spiderman, and several other shows. Artworks: Eighty eight (88) 360 degree panoramic photographs custom printed by the artist. The photographs are printed in a variety of sizes ranging from 10 x 30” W to 24 x 72” W. Artifacts and Ephemera: Bedford Gallery will supply an open list of the appropriate Broadway contacts to procure props, costumes and other artifacts to supplement the exhibition. Space Requirements: 2,000 – 4,500 Square Feet or 250 – 400 Linear Feet This show is elastic; a small selection of the photographs are available in varying sizes to allow each venue design an exhibition that gracefully fills the exhibition space.